From the legacy of Hija de Perra, Danka Herrera looks at the politics of the bodies of sexual dissidence: to write in order to live.

To write under

the pressure of war is not to write about the war but to write inside

its horizon and as if it were the companion with whom one shares

one’s bed (assuming that it leaves us room, a margin of freedom).[1]

–Maurice Blanchot

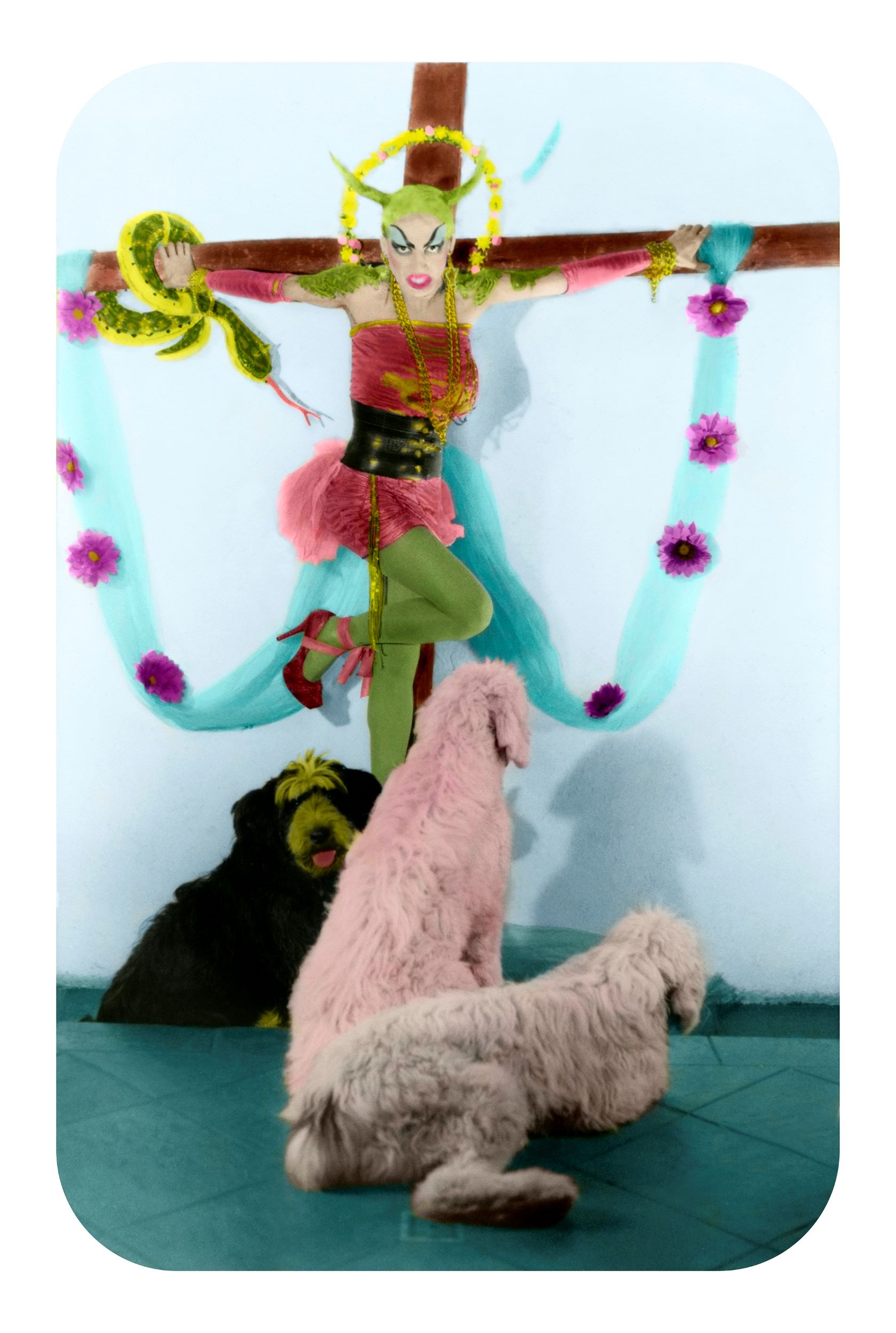

Among those who articulate the relentless struggle against the unrestricted violence of the cisheterosexual-colonial regime, calling themselves sexual dissidents, the figure and legacy of the visual artist-performer Hija de Perra is well known.[2] She was part of a scene filled with fury against the image that was rising between the 1990s and 2000s of the bloody reconciliation of the traditional male left with the perpetrators of one of the most devastating military dictatorships in Latin America, the military group headed by Augusto Pinochet Ugarte. Hija de Perra is an artist against compromise. Against the clean slate that left a society marked with more than one thousand disappeared detainees, making Chile the perfect geopolitical space for the rise of neoliberalism. A devastation with signs as clear as the collapse and silence of the political voice. Hija de Perra uses performance, sewing, and heels as sharp weapons that break the pact. She is an active participant that breaks through the fossilized industrial mantle of sexual memories. Sexuality as a political space, stressing the horror of cultural impositions from Columbus to Pinochet, from Pinochet to the fragmented supporters of cisheterosexual politics. Hija de Perra exposes the accomplices, the so-called pacifists who at gunpoint and with “morality” impose one of the most violent and bloody regimes in history. A regime that thinks about History. The artist of fissures, of escapes, of overflow, and of embraces. Not everything appears in the gesture of decomposing. It is about using the body as an insult, which embraces the insulted. A weapon of support and action. Hija de Perra opens a door, which was firmly closed with marble and machine guns, to rethink the status of the political in sexual dissidence, letting in all the little monsters thirsty for revenge. It deals with a body-prosthesis that shapes the traditional asphalt politics of capital into the dissident politics of sand. The dissident politics found in the desert. The given conceptualizations of capitalism in its functionality move in an architectural network with a solid support. This is how it compares to asphalt. A politics that crushes, a politics that solidifies as foundation, soil, and reality. Sexual dissidence operates in its production, resistance, and evolution in the desert, where solid constructions tend to fall down with the movement of the soil, in its characteristic change. Politics in the desert have no fixed conceptual frameworks, they are subject to historical evolution. They are mobile, molecular, without foundations. Desert bodies, of margin and abandonment. Hija de Perra is an outsider artist. A revolutionary artist of and from the margin.

Degrees of care in the monstrous before taking a stand: Hija de Perra as pietà.

“After my nightly masturbation, I will continue dreaming and imploring the universe that Latin American education will change and that from the origin of human formation this type of knowledge will be used, so that our children, clean of imposed generic impurities, will be educated free of social stigmas,”[3] says Hija de Perra back in 2014. In the text from which I extract this quote, the author worked relentlessly to trace the entire history of colonial rule since the Spanish invasion. This gesture of attention to history is a show of how history is passed on generationally as well. The artist is clear on the historical emphasis of the sexual reading. In the seventh thesis of the text On the Concept of History, Walter Benjamin affirms this gesture: “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. And just as such a document is not free of barbarism, barbarism taints also the manner in which it was transmitted from one owner to another,”[4] Thus, we affirm: There is never a document of culture that is not sexual and, at the same time, a document of barbarism. It is from this framework that Hija de Perra writes and inscribes. But this tool of historical optics alone is not enough without the reference to the body that suffers the scourge of hegemonic history. This is the meaning of the first quote: to turn to multiform childhood as a place of heterogeneous and ambiguous sexual convergences. Implicitly, to carefully watch the bodies that make their own bodies instruments of the flow of desires. We can ask ourselves then, is the gesture of Hija de Perra not an act of memory? Could it be that Hija de Perra, in her pageantry, cradled the lost strangeness of childhoods thrown into the sexual desert? This act of bringing bodies “without history” back to the present with images of resistance is the main configuration of the monstrous in its sexual evolution. They are without history for two main reasons. Firstly, because sexually dissident bodies do not exist in the official historiographic production, or at least, the most visible one. Secondly, given that the archives that compile sexual history and its signs are not problematized as historical politics. There are bodies that deserve to have their stories told, according to the hegemonic eye, and there are others that do not. Ultimately, sexual dissidence and its historical production reside in the bodies that do not matter, bodies that do not exist. These bodies without history produce resistances, produce times and images different from that of the cisheterosexual normative, and also, therefore, degrees of contention within the [counter]production of concepts. This sublime image does nothing but turn the artist into a symbolic figure of pietà as soon as the sexual dissident struggle between resistance, fall, and death is understood. Life fractured with death as part of it. Not just any death but a persecutory one. Paz López says:

“Between the one who is going to die because he is a man and the one who is going to die because the bloody hand and the cruel eye of history have rested on him, a sewer is formed that binds together everything in the world that belongs to horror. [ . . . ] I am thinking of works that hold the tormented and dispossessed to their bosom, those bodies that balance on the margin of the visible, of what is finished by history but remains unfinished in its power.”[5]

The symbolic figure of pietà in Hija de Perra molds the importance of a radical sexual empathy. An affection of companionship, of care, and undeniably of sustenance is undeniably needed to perform survival along with the deployment of the body as a sexual war machine in conflict. The lives of these bodies need to heal their wounds after years of stumbling and escape. To understand this fall in experience, as Marcela Rivera indicates, is to say: “The experience of the fall, insofar as it always implies a vacillation of our certainties, a trembling of the firm ground that we assumed to be immobile under our feet, teaches us to move between the high and the low, to compose ourselves with the experience of fragility and variation. In Montaigne, experience is inseparable from the fall, from what in ourselves is allowed to fall,”[6] To fall into survival is always to need the arm of radical sexual empathy. The pack of sexual dissidence operates in terms of support in the storm. Hija de Perra becomes a wolf, and also a kind of magnifying glass that allows us to read, in Benjaminian terms, against the grain, the history of those without history. Hija de Perra, in her sexual terrorism, in her figure that is uncomfortable to the capitalist cisheterosexual eye, moves in the wandering, that is to say, to conform a figure that is not afraid of failure. Ultimately, a figure that guides the herd to not be afraid of falling.

Exile and writing: Meddling, using heels without permission.

Left behind in history in the sense of being forgotten. In being placed under the carpet so that the capital image is unpolluted, sacred. Exiled from the historical records. No trans-travesti body is recognized in the Rettig Report or in the Valech Report as a subject of disappeared detainees. We are exiled from recognition, from our voice and history. Exiled from love, conventions, and political activity. It is not an eagerness to integrate—and we should be very careful with that—it is bearing witness that in the conceptual places where cisheterosexuality operates they are a one-way street. In a totalizing path. Monique Wittig makes it explicit: “The straight mind is clothed in its tendency to immediately universalize its production of concepts into general laws which claim to hold true for all societies, all epochs, all individuals. Thus one speaks of the exchange of women, the difference between the sexes, the symbolic order, the Unconscious, Desire, Jouissance, Culture, History, giving an absolute meaning to these concepts when they are only categories founded upon heterosexuality, or thought which produces the difference between the sexes as a political and philosophical dogma.”[7]

It is in the writings of these exiled bodies that a matrix of cisheterosexuality is decomposed. It is not originally written with paper and pencil. Sexual dissident writings began from orality, from aesthetics. Writing is given when entering the public space without permission. The writings are executed in the frame where the sexual dissident body intercepts with the common. Then, as sexual dissidents learned to write on paper, another way of writing began to appear in the grammatical framework. This is where the state of things is endangered. To challenge this dominant writing is to challenge the order, thus, paraphrasing Pasolini, writing becomes meaningless. The thirst to write translates into a thirst to leave a trace, to stain.

Claudia Rodriguez, a trans poet, says: “Maere, I don’t want to go to school / All the lyrics I learned spoke of the end of the world. I grew up with fear of falling out of the world, of the world ending at any moment. I grew up afraid of being a spider, selfish, afraid of wanting to be happy. In school, terror flooded my body and I learned to always see myself as bad. Because of this ugly madness of wanting to be a little girl. / They gave me two notebooks and a pencil and said that hair grows, so I just had to let time pass and I would go back to being the same, but neither my name nor my voice were what anyone expected. / Maere, I was born where no one wants me.”[8]

Ultimately, the only place where sexual dissidence was not exiled was in writing.

That is to say, it was from the scriptural sidewalk that they entered the world of politics. Whether through orality, through their sublime images-writings, or handwritings.

Hija de Perra writes within all of these terms. Hija de Perra writes to live. She knows she lives inside a mass grave called the Southern Cone, but without writing there is no way to articulate a survival in the endless advance of the homogenization of sexual experience in geopolitical spaces.

Hija de Perra bombards us with writing, literally.

Comments

There are no coments available.