10.07.2020

Ante un panorama donde el futuro pareciera haber fracasado, el historiador del arte Nicolás Cuello apuesta por temporalidades queer alrededor de la afectividad, la multiespecie y la fantasía de los futuros cancelados.

These are strange times. This is one of the few certainties that the collapsed structure of our present moment offers us. The imaginaries that make up the uncontrollable dream of the possible are in a profound state of crisis: a crisis of immobility produced by the institutionalization of fear in the place of the word future. Systems of internalized precarity arising from the forced mortgaging of human existence, the social pressure seeping out of the vertical structures of subjective success in the new corporations of the I, and the imaginative cancellation of every alternative to liberal configurations of the present have resulted in the restriction of one of history’s most profound vectors of insubordination: fantasy.

When we talk about a crisis of political imagination, we are referring to a conjunction of limitations programmed on a global scale that aims to interfere in the Other’s capacity for speculative experimentation. We are referring to all the identifiable modes of symbolic control over desire that are silenced because the forced incorporation of capitalism is the only possible avenue of evolution left for the cultural subconscious. Within this crisis, we realize that the symbolic walls and emotional traps with which the forced naturalization and assimilation of all alternatives to reality surrounds us serve as regulatory fictitious daydreams that, simultaneously, stifle the expressive capabilities of new political languages.

We can trace the genealogy of this obfuscation to the profound effects of control propagated by the popularization of what Francis Fukuyama calls “the end of history.” For Fukuyama, the fall of the Berlin Wall was the event that silenced all global revolutionary processes and established the existential outlines of capitalism’s political project: the capitalist state was represented as the logical conclusion of an organic, coherent, and self-sustainable evolution of social organization, a lifestyle whose principal guarantee lay in its ability to constantly update and strategically reformulate itself to enable the uninterrupted extraction of surplus-value based in a project of corporeal alienation of unprecedented proportions. The inevitable development of the neoliberal project as an imaginary city protected from the possibility of drastic transformation not only made official the failure of the fragile cartography of socialist projects that had been developing over the course of the eighties, but also formalized the end of the time’s arrow in historical terms.

[…] the queer becomes necessary, not as the embodiment of a liberatory horizon that mediates identitary terminology, but rather as a mode of disidentification that undoes time’s repetitive logic. In it, the illus0ry narrative of constant fluency becomes a structure out of which reality can be programmed and the normative conditions of intelligibility of history and our bodies are hidden.

Mark Fisher locates the failure of the future, or the project of its slow cancellation, in the institutionalization of risk-averse cultural models, of a weakened politics of imagination, and of social imaginaries that have been stifled by the obligation to turn a profit, and all of these partake in an obsessive backward gaze to the sticky pit of the past. In place of the concept of postmodernity, which Fredric Jameson proposed as to describe late-stage capitalism’s cultural logic, Fisher invites us to think about capitalist realism, a term that describes the colonization of the capacity of invention by an Other, a process which naturalizes the axiomatic violence of financial destiny, a destiny in which “there is no alternative to that which we know.” That is, in this future there exist none of the social conditions nor the fantastic tools that might enable the imaginative emergence of new modes of organizing the social, ones that could guarantee the capacity for their creation and the concrete materialization of their sustainability. This does not mean that there is no room in the present for the emergence of the independent, the autonomous, or the alternative. What is practically nonexistent in the present, however, is the emergence of said desires in channels outside of reproductive logic of the mainstream, given that the longevity of capitalist norms will continue to triumph so long as capitalism can anticipate and subsume into itself any condition that might lead to a challenge to its power. It does so by deactivating the revolutionary potential of cultural movements through the logic of the spectacle, pre-codifying the characteristics of social landscapes through media pressure, pre-producing forms of social contact through the technological incorporation of biopolitical control, and installing in the subjective order the cruel promise of entrepreneurial internship, a new regimen of time with no real future.

The crisis of critical thinking and the disappearance of leftist political efforts on a global scale resulted in the loss of the generative, future-looking aspects of the antagonistic imagination and reduced it exclusively to its negative traits: its mere propensity for opposition. When faced with institutionalized repertoires of protest (which include the collective occupation of public spaces and the creation of sensible terminology for critical intervention), Fisher recognizes speculation as a possible mode of radical transformation and emancipation for social conditions. For Fisher, one can stop the monopolization of the future by mobilizing modes of indirect action based on a politics conscious of the coming disobedience. These modes include the creation of new ways of coming into contact with fantasy, new images for science fiction, and other speculative languages that deal with the sensible articulation of tomorrow.

Given the strength with which the direction of our desires has been culturally sealed off from our capacity for dreaming, it is not advisable to romanticize the return to the future as an outdated mode of inscribing anachronic revolutionary sensibilities. Rather, the future becomes a new mode of approaching the past which grips us through a hauntological or spectral code; through a recognition of the abrasive immobility in which we have been sunk thanks to the ontological nature of the postmodern historical loop, it is possible to playfully activate a reclamation of what was, what could have been, or, even, what could be. This is fantasy’s phantasmagoric condition—one that can be positioned as a virtual agent of the emotional-political reorganization of the emergence of the possible, the concentration of the strange, and the sustainability of the alternative.

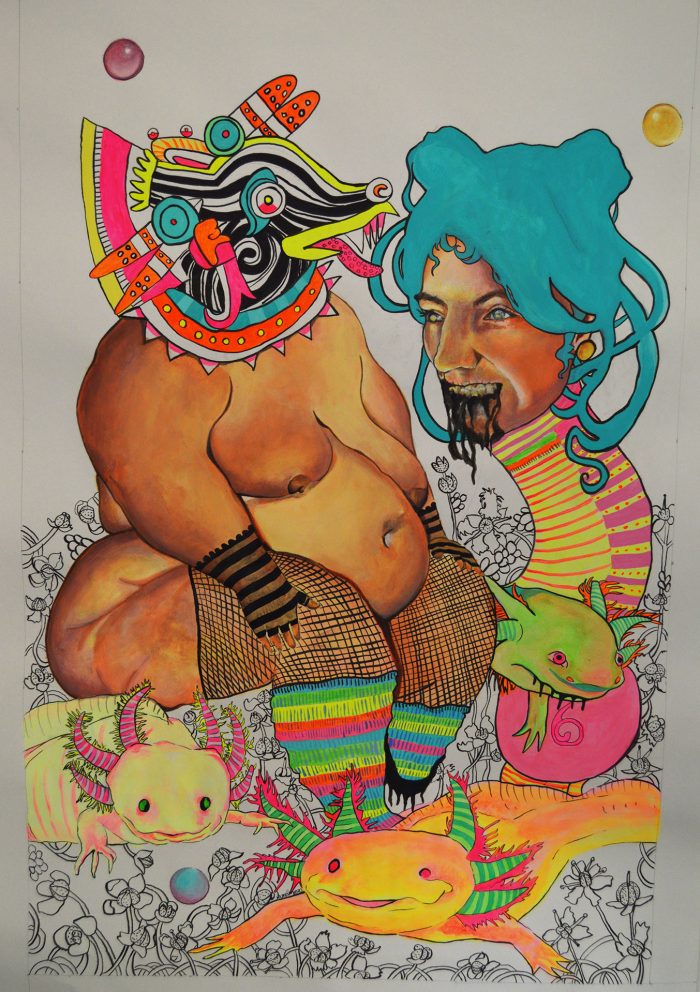

Thus, we must turn to artistic processes such as appropriation, pastiche, and collage—modes that define our relationship with time—in order to listen to cancelled futures. From there, we can practice creating images that inspire us to strip institutionalized narratives of what is to come, narratives that function beneath the sign of a positivist and linear mono-language, a prospective architecture obsessed with the discourse of a specific futurity that, according to Lee Edelman, exists only as a heterosexual machine of identification that only guarantees capitalism’s reproduction as a mode of cultural and political organization.

And this is where the work on the queer becomes necessary, not as the embodiment of a liberatory horizon that mediates identitary terminology, but rather as a mode of disidentification that undoes time’s repetitive logic. In it, the illus0ry narrative of constant fluency becomes a structure out of which reality can be programmed and the normative conditions of intelligibility of history and our bodies are hidden. It is not about actualizing the revolutionary epic’s androcentric languages, rather, it is about actualizing minoritarian modes of action that resemble those of the past, problematizing those regulatory fictions that block or control the political culture of antagonistic emotions.

The irruption of the queer as a mode of making in and over time allows us to glimpse new modes of hauntological contact, new spectral conversations with the past that, through the fantasies, they offer up to exploration, create the codes necessary for a revision of the conditions of the present. Thinking about a queer futuristic imagination implies developing assemblages and dispositions that complicate the imperative of a linear and transparent relationship between past, present, and future, delineating a perverse turn that distances us from the narratives of heterosexual consistency and capitalist economies of the present’s reproductability.

Thinking about what conditions of possibility can make way for new ways of imagining the future not only implies identifying those conditions which prevent this from happening in the first place, but also outlining those that make said alternative modes of desire possible. The argument, then, is a call for an urgent revision of the political historiography of tomorrow’s fictions, fictions in which we can already see the organization of our desire according to tropes that replicate visual policies and affective cadences that naturalize our inability to question our surroundings: we are overwhelmed by dystopian language describing putrefied landscapes of dead earth, societies enslaved by artificial intelligence, cities crumbling beneath a mantle of pollution-generated rust, ableist imaginaries of bodies immobilized in a state of virtual reality as totalized experience, a world where misogynist violence marks its territory on feminized cyborgs while speciesist colonialism and interplanetary imperialism are championed as the only logical means of survival. There, in those geographies where the multiplicity of the speculative is displaced, we can see the beginnings of a reality that cannot be cancelled: the reproduction of the political, economic, sexual, and environmental order that capitalism expresses through the ceaseless continuity of a contemporary mode of production of existences that includes the bureaucratization of power, imbalanced relationships with and the extractivist exploitation of the environment and non-human species, forms of corporeal hierarchization, and structural violence towards sexual difference.

Donna Haraway argues passionately that dogs—of all species!—can, in our spectral modes of contact with the past, offer us a means through which we can reconfigure our desires for a future while dismantling the threat projected on tomorrow. In 1985, Haraway’s essay The Cyborg Manifesto attempted to give a feminist sense to the implosion of contemporary life around technoscience. The popular presence of the cybernetic organisms in that time was a response to the techno-humanist imperialist fantasies constructed in the wake of contextual narratives such as the beginning of the total cancellation of the alternative thanks to the Cold War and the advent of new cultural revolutions that promised total disarray. Haraway’s description of the cyborg, in turn, proposed a critical language through which to think about the link between the human and the nonhuman, the organic and the technological, carbon and silicon, the rich and the poor, the state and the subject, modernity and postmodernity, but, most of all, the present and the future.

The enthusiasm for technological effervescence corresponded with the explosion of fantastical images that spurred a rethinking of the boundaries established by machinist scenarios of the production, reproduction, and imagination of the socio-sexual order through concrete strategies of change, disruption, and denaturalization. These strategies warned against technology’s role in the construction of normative sex0-gendered subjectivities. They suggested instead a mode of doing committed to bias, irony, intimacy, and the perverse deviation of signifiers as much as to the utopian hope that the technological might offer a possible answer for new life forms.

However, towards the end of the millennium, Haraway recognized that cyborgs could no longer provide the conditions necessary for a critical investigation of the mutability of coexistence or of the political development of living conditions. In their place, the history of companion species provided an opening for new images of cohabitation, coevolution, and sociability. In its refusal of typological thinking, Haraway’s feminist theory of interspecies cooperation contributes to a rich unfolding of approximations of emergency, historicity, specificity, cohabitation, constitution, and contingency. For Haraway, a feminist understanding of our relationship to the species that surround us entails building an understanding of how things work, of what might be possible, and of how the actors that make up this world might love and care for each other in less violent ways—in a way that finally takes difference into account. Her 2006 Companion Species Manifesto became, in her own words, a demand for kinship, a global call for the consideration of interspecies relationships through what she names significant othering, a process through which we leave behind anthropocentric, speciesist parameters and function within a new reality that explicitly marks the partial connections that join us in a web of techno-organisms, delineating patterns of common habitability where actors are neither part nor whole, but rather life forms that establish agency contingent on our inherited histories for the prosperity of a shared future.

Through the history of dogs, Haraway underscores the importance of thinking about interspecies contact outside of transferential humanity, departing from the narrative that is usually proposed by hetero-productive imaginaries of the nuclear family. In their place, she calls for the recognition of dogs as who they truly are: dogs, a different species. Not the projection of an individual, nor the representation of a frustrated human intention, not anything else’s telos, simply dogs, a species with an obligatory, constitutive, historical, and prosthetic relationship to human beings. The accepted narrative about humans’ historical contact with dogs recounts an inevitable and contradictory history of constituent relationships wherein neither of the companions preexists their relationship, a relationship that never ends. The companion animal penetrates techno-culture, highlighting the intersection of technoscientific experience and late industrial practices of care, which in turn illuminates the implosion of nature and culture in the relentless and historically specific shared lives of dogs and humans, who have been brought together through an act of significant othering. Thinking about our relationships of companionship with other species is a political act of hope in a world on the brink of global warfare; it is a task that must be continuously performed and that seeks to finally locate an ethics and politics committed to the prosperity of othering, taking the relationships between animals and humans, as well as the environment, seriously. In this manner, animals are not the objects of our own reflected desires, but rather the condition necessary for the emergence of an ethics of companionship and cohabitation that proposes we work on bettering conditions for sustaining life.

On a global stage of violent organization with the totality of all other species, producing images that disrupt its communicative logic and the cruelty of its contact may push us towards the phantasmic work of creating that which could come to pass, but still has not: an animalistic utopia of the commons. A place where our reciprocal relationship (that arises from an ethical recognition of our difference) allows for the emergence of a different future based on the ethics of prosperity and which takes responsibility for the material and symbolic disappearance of nonhuman animals.

If the languages of culture industries have systematically proposed dystopian representations or fantastical elucidations of the future that are organized around the multiplication of speciesist interstellar suffering and reproduce the vertical beginnings of anthropocentric power, our job is to repair strategies that could reconnect us with the demand for techno-organic cohabitation, recognizing in it and in its affects the possibility of a new consciousness about what tomorrow needs. We are talking about political feelings that can help us to think about animality outside of the conditions of pethood determined by the market economy, that alert us of the permanent state of evanescence in which species find themselves as the environment slowly collapses and that can, once and for all, incite us towards the dismantling of the carceral monumentalization that are zoos, those living museums of abuse.

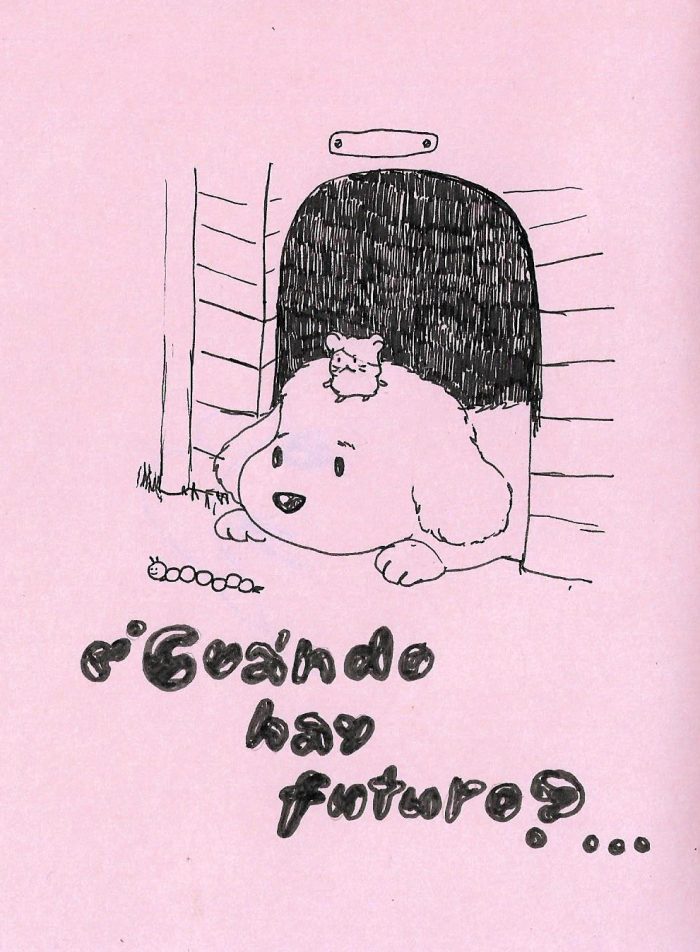

The disidentification with those registers that introduce, in a sensitive key, the animal as a threatening collapse, as the expression of barbarity, and as a moral peril whose persecution constitutes the organizing precept of the human world, is possible through the intensification of the minor affects and ordinary sentiments such as tenderness, the “cute,” and the naive: feelings which can begin to repair the damage that structures our distance from those species with whom we must share the world and our livelihood.

We are speaking about affects which, in contrast to the emotional registers of political agency, circulate through economies of low culture, appearing in ways that respond to the systemization of the everyday, the industrial reproduction of mass culture, whose significatory resonances have been traditionally historicized as lesser than.

The imaginaries that make up the uncontrollable dream of the possible are in a profound state of crisis: a crisis of immobility produced by the institutionalization of fear in the place of the word future.

In contrast to the profound complexity that characterizes the sentimental structures in which the subjective mutations of an epoch can be recognized, Sianne Ngai tells us that although these milder affects are often written off for their supposed constitutive incapacity to carry complex meanings that could aid in the designing of future politics, they, in fact, carry the promise for new modes of relationality between subjects and objects.

If it is true that the growing instrumentalization of these specific affects in and by the logic of mercantile identification contributes to their weakness at outlining a diagram for a new political sensibility, the tender, the cute and the naive offer us the opportunity for coming into contact through simpler experiences free of the moral constraints of the profound.

The instant gratification, quick affirmation, and immediate pleasure that these affects provide must be read from the point of view of an unstable relationship with the rhythms of commercial identification within the logics of global consumption. Their textures are composed of soft characteristics; and although they may come from the sphere of mass culture and the emotional dumping grounds of sentimental political truths outlined by patriarchal regimes, their apparent incapacity for confrontation with power deprives us of recognizing their oblique capacity for intervening in reality. Just as previously mentioned in relation to fantasy as a form of indirect action, or interspecies companionship as an ethics of care capable of transforming the cultural-political structures in place, affects such as the tender, the cute, and the naive—and the relaxed feeling they inspire—remind us of our capacity for love and bring back the possibility of communicating affection, expressing worry, and protecting that which does us good. Ngai tells us that rather than rendering them inoperative within the mainstream political sensibility that centers on a radical image for the future, the unease that their diminutive corporeality and their defining infantilization elicits remind us of (once they are within us) their leading role in the production of desire for care and protection: a task historically relegated to the feminized bodies that has usually gone unrecognized and whose importance is substantial for the possibilization of the social and the political. Those images that we can identify as tender, as cute, as naive speak of fantasy’s potential in the labor of creating loving recognition between subjects and even between species. Their apparition demands our help, mobilizes empathy, asks for care, makes us capable of listening to that which asks for affection, that which asks for love, and so makes us capable of protecting it, guaranteeing its existence alongside us.

In the midst of a global climate obsessed with the endless reproduction of that imaginative frustration where the potential desire for transformation of reality can be found, those obsolete, impossible, and strange languages of fantasy allow us to connect with the possible emergence of a different ethics of shared existence. Allowing us to question those under-considered companion species—whose imminent extinction deprives them of their own tomorrow—and those feminized affects (banned from languages of antagonistic political imagination) can be a model for transforming our capacities for desire, binding us in the creation of projects of techno-organic sensibility whose relationship to othering will be the guarantee for the multiplication of possible worlds and strange modes of inhabiting, together, the experience of living.

—

This text was originally written for the Expanded Painting and Speculative Fiction Symposium organized by Ad Minoliti within the framework of Art Basel Cities, Buenos Aires (2018).

Comments

There are no coments available.