05.07.2021

As a tribute to land rights defender Don Temístocles Machado, researcher David Gutiérrez and artist Liliana Angulo Cortés share with us the living memory of a community that resists the developmentalist and ecocidal imposition of the Colombian government.

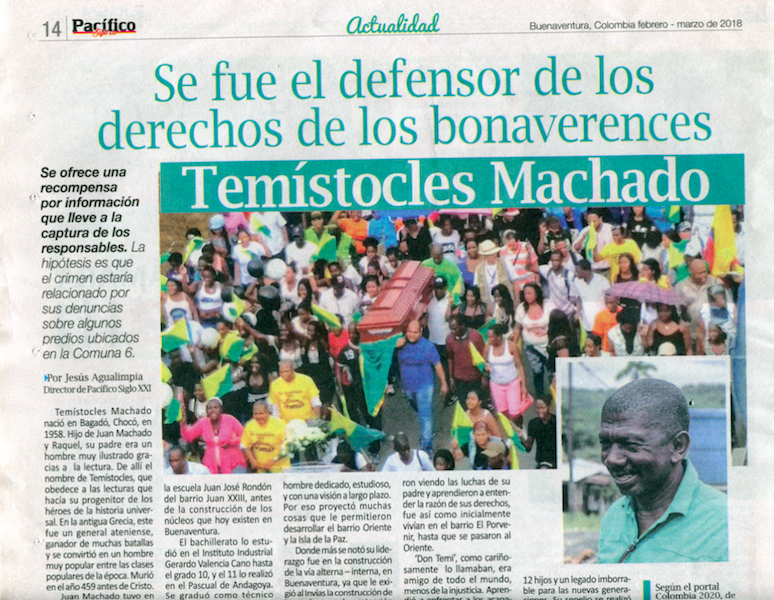

Temístocles Machado Rentería was a community leader of Comuna 6, Buenaventura, Colombia, including the neighborhoods Isla de la Paz, La Cima, and Oriente. He was a member of the Civic Strike movement and a human rights defender, archivist, and documentarian, as well as an empirical lawyer. Temístocles Machado Rentería was murdered on January 27, 2018.

Grupo Memoria y Archivo de la Comuna 6 [Memory and Archive Group of Comuna 6] is a group organized around the legacy of the life and struggle of “Don Temis,” made up of leaders and artists who have come together to continuously demand a just life for the Black and Indigenous communities of Buenaventura facing port finance capitalism. Artist Liliana Angulo Cortés has collaborated with the community on cultural practices, memory, documentation, and intervention in the territory’s community spaces as relevant actions for this struggle. This is their story.

BUENAVENTURA, VALLE DEL CAUCA, COLOMBIA

Inhabited mostly by Black and Indigenous communities, Buenaventura is a city district located in a bay on the Pacific coast of Colombia. It is home to the country’s main port. The first port terminal was located on Cascajal Island. With the expansion of the city, rural areas of the territory of Buenaventura were incorporated into the urban area on the mainland. The city is located in the middle of mangrove ecosystems and a marine reserve threatened by the expansion of the port.

BUENAVENTURA’S PORT DEVELOPMENT PLAN

The entire territory of Buenaventura is considered to be within the port development and expansion plan slated to occupy areas inhabited by the communities as well as flora, fauna, and maritime natural reserves.

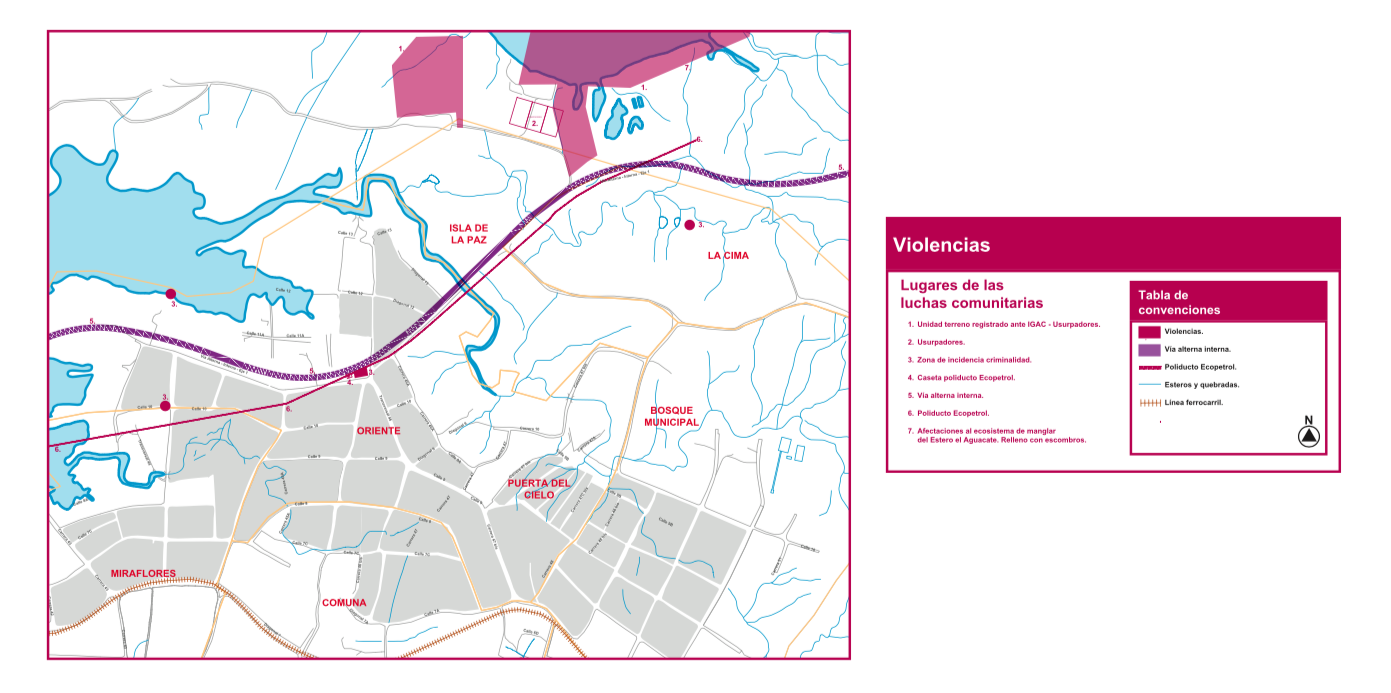

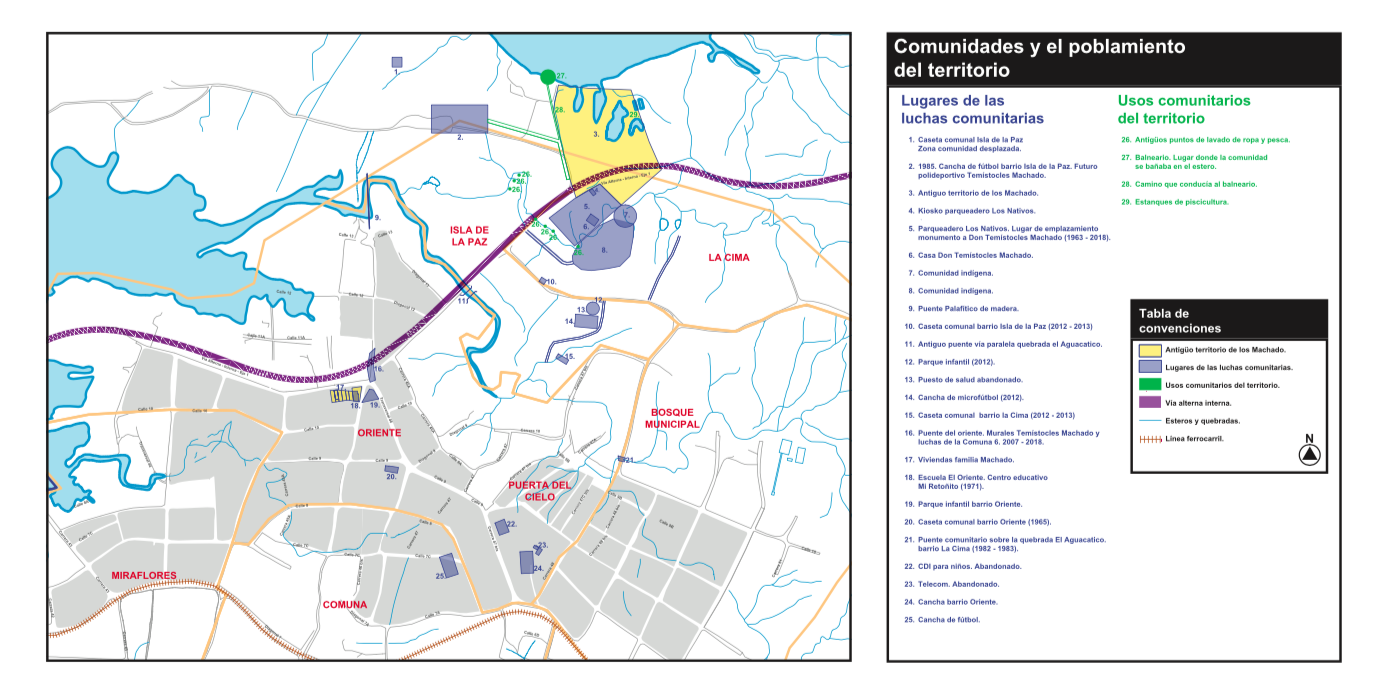

In the case of the Oriente, La Cima, and Isla de la Paz neighborhoods located on the mainland along the El Aguacate estuary, they are seen as parking, cargo storage, and logistics areas. Since they are crossed by the Vía Alterna Interna corridor, their location makes them a prime target, which has generated multiple processes of violence that include deceitful expropriation of land from families by the state, usurpation of land through false private deeds for storage areas, parking, and port development, as well as areas with high crime rates, and an oil pipeline that bisects the community. This is imposed development that does not include the visions of the community and only benefits investors interested in new docks, a cargo airport, container storage areas, and tractor-trailer parking. This type of development only benefits international capital and free trade agreements between countries that are part of the Pacific Alliance.

«These neighborhoods that you have seen are not urbanization made by the state […] these neighborhoods are made by hand and on the shoulders of the same community carrying a stick, pulling a shovel […]» — Don Temístocles Machado

WHERE DOES DON TEMÍSTOCLES COME FROM?

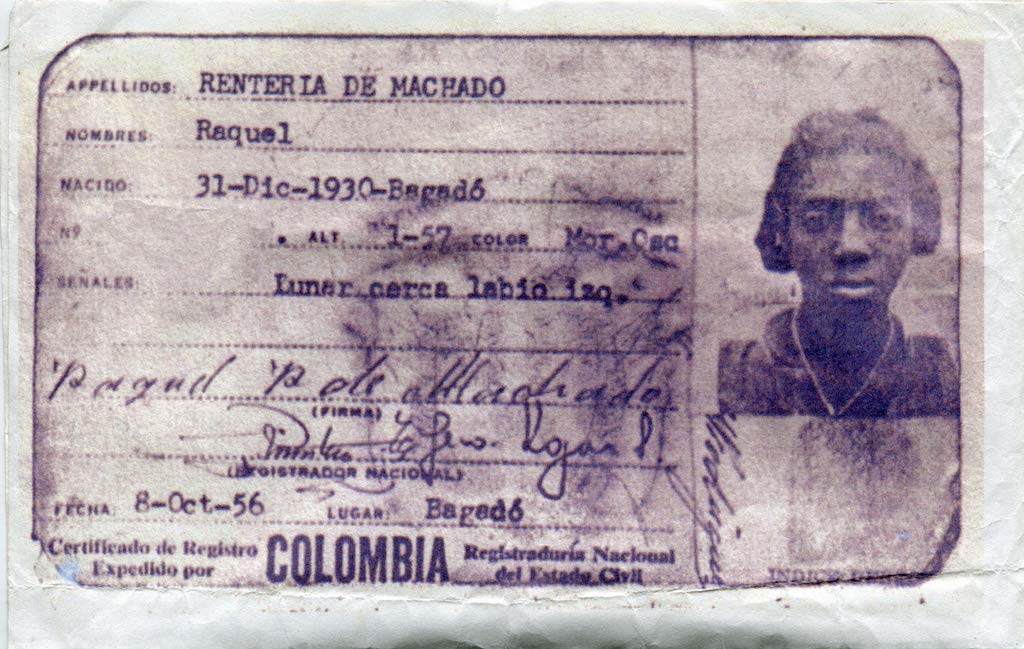

Don Temístocles is part of a lineage of community leadership. His parents Juan Evangelista Machado and Raquel Rentería, from Bagadó, a former Maroon community in Chocó, were among the first settlers of the area now known as Barrio Oriente. Subsequently, Barrio Oriente was divided, giving rise to the neighborhoods of Isla de la Paz and La Cima. Their first family home in Buenaventura was affected by the construction of Simón Bolívar Avenue, the result of the highway to the sea that connects the port with the city of Cali and the interior of the country. The family later relocated to the Oriente neighborhood, and history repeated itself with the construction of the Vía Alterna Interna.

COMMUNITY WORK OF DON TEMÍSTOCLES

Temístocles Machado was an activist in defense of the territory and the rights of the community in the face of development projects imposed by the state. He was president of the community action board of Barrio Oriente. As a social leader and cultural and sports manager, he was able to build and improve community spaces. He was a leader in love with his territory and the culture of its community. Faced with land usurpation, threats, and violence generated by imposed projects, he became an empirical lawyer as a strategy against judicial and bureaucratic corruption. He developed an archival practice to preserve information from legal proceedings for the defense of rights, documenting the memory of the community and environmental impacts. Through his struggle, he denounced structural racism, was a promoter of territory debates, and a member of the Civic Strike committee to live with dignity and peace in Buenaventura. Over time, the leadership of Don Temis transcended his community and intersected with other social and political processes in Buenaventura related to struggles throughout the territorial due to port expansion that does not take the community into account. The violence in Buenaventura responds to the macro-projects, presented to generate terror and displacement of its inhabitants.

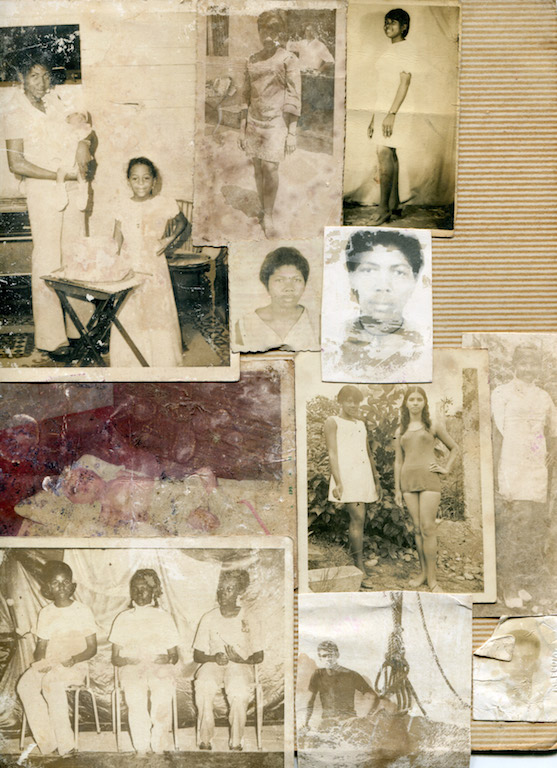

TERRITORY OF BLACK AND INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES

The territory of Comuna 6 where Barrio Oriente is located was a rural area where these families developed their agricultural, fishing, and mining activities. Subsequently, the first settlers in the area founded neighborhoods and established forms of coexistence based on the traditional collective organization of the Black and Indigenous communities, such as Minga[1] and mano cambiada;[2] they created roads, public services, schools, recreational areas, and public community areas. The founding families of the area still preserve documents of the first settlers and memories of their achievements. In Colombia, the visual memory of Afro-descendants has generally been mediated by the gaze of outsiders. These images of families are valuable because they show daily family life in the Comuna 6 neighborhoods of Buenaventura on their own terms.

DOCUMENTATION OF CULTURAL PRACTICES

Anticipating environmental damage and territorial harm caused by government development projects and third-party interventions, Don Temístocles undertook activities to document and recognize the communities’ lands in order to defend them. He defended the traditional practices of the Black communities that maintain a relationship of sustainable reciprocity with the environment. These images from Don Temis’ archive show the El Aguacate stream, the estuary, and native crops. Before the construction of the Vía Alterna Interna, Don Temis conducted tours of the territory as a strategy of recognition and control of the estuary, and community awareness around the protection of the territory and its ecosystem. The mangrove ecosystem is a fundamental part of survival and food sovereignty for these communities. They fish and also navigate the estuaries as a way to transport their crops and timber to the Buenaventura market. Activities native to the territory include fishing, gathering seafood, and artisanal mining. Don Temístocles Machado documented the cultural practices of the community because one of his greatest dreams was that they would be able to preserve their ways of inhabiting this territory. Now the land, estuaries, streams, and rivers have been invaded by land-grabbers, and water resources have been polluted.

«I am from the countryside and I can never forget my roots, where I come from; by the fact that I am in the city I don’t stop being Black, no! ” — Don Temístocles Machado

RADIO CONVERSA, PROJECT BY OSCAR MORENO

In the program, Don Temístocles Machado, who had a prodigious memory, describes how communities populated the area in the twentieth century. He also explains the violence to which they had been subjected, and the community struggle in the face of state-imposed and port expansion projects that seriously affect the area. In November 2017, we reached an agreement with Don Temístocles to work with his archive and the community. How to communicate the archive was the question to be answered which gave birth to the Archive and Memory Group of Commune 6.

“This has led us to create an exercise of kinship between us […] to discover the power we have.” — Don Temístocles Machado

THE MONUMENT TO DON TEMÍSTOCLES AND THE SITES OF COMMUNITY STRUGGLE

The Archive and Memory Group of Comuna 6 identified nine community spaces that represent Don Temístocles’ struggle for the defense of the territory of and its communities. In these spaces, signs marking the chronology of the settlement were built, and they are part of the monument to Don Temístocles Machado that expands throughout the neighborhoods of Comuna 6. Between these spaces a connection was generated that also functions as a way of traversing the territory through the denunciations, violent events, and victories of the community.

The mural painted on the Barrio Oriente Bridge over the Vía Interna Alterna marks one of the main victories of the community led by Don Temístocles Machado against the city’s road administration. The mural was intended to “humanize” the Vía Interna Alterna, a highway where the constant traffic of trucks and cargo makes the communities that live in the area invisible.

“[In the seventies] the community was very civic […] mingas were practiced a lot—a minga is when a group of neighbors, friends, residents of the same sector, unify in order to carry out an activity in search of well-being for the same community.” — Don Temístocles Machado

CREDITS

Grupo Archivo y Memoria Comuna 6 (María Elena Cortés, Arcesio Izquierdo, Ana Campaz, Delcy Castro, Juan David Romero, Patricia Herrera, Juan Rodrigo Machado, Eloisa Machado, Magno Machado, Carmen Chávez, Janer Panameño, Hernán Rodríguez, María Esilda Estacio, Oscar Moreno Escarraga, María Santos Caicedo, and Liliana Angulo Cortés); the communities of La Cima, Isla de la Paz, and El Oriente

PRODUCTION

Asociación Cultural Rostros Urbanos—Jonathan Hurtado

PAINTERS

Jose Luis Rodríguez Garcerá and Lenz Smith

COLLABORATOR

Luisa Jaramillo Angulo, Temístocles Machado Archive and Monument Laboratory coordinated by Liliana Angulo Cortés; carried out within the framework of Carretera al Mar, Goethe-Institut Kolumbien and Museo La Tertulia.

All quotations throughout this article are fragments of the conversation with Don Temístocles Machado as part of Radio Conversa, chapter: Ciudadanías Ancestrales, a project by Oscar Moreno Escárraga.

“Minga is established as a historically constructed process which has its beginnings in the social struggles developed [in Colombia] from the seventies until now. It has become a stage where the social sectors have been in constant search of a space of recognition and autonomy both in the public and private spheres, where they no longer fight about difference (as they did in the nineties). Rather, it is that difference that unites them and allows for each social organization to become involved in a joint project, through the construction of platforms of action and struggle for common objectives and in accordance with

the common good.” Alen Felipe Castaña Rico, La minga de resistencia social y comunitaria: construcción de proyecto de movilización popular bajo lógicas de articulación intersectoriales [Minga as Social and Community Resistance: Building a Public Mobilization Project Under the Logic of Intersectional Coordination] (Universidad ICESI, 2017), 7

Local ancestral practice that means “trade exchange.” It is based on solidarity and peer relationships over money.

Comments

There are no coments available.