Sam Durant, Rafa Esparza, Sandra de la Loza, Iván Argote, Pilar Tompkins Rivas

Reading time: 14 minutes

09.10.2017

Pilar Tompkins Rivas reflects on the importance of questioning historical narratives and the infrastructure that sustains them in light of the recent events in the United States around the protest and removal of confederate monuments.

As the academy and the museum (and by proxy the market) are structured to foreground particular narratives, the ongoing question remains about what gets left out of art history.

Christopher Mele, “New Orleans Begins Removing Confederate Monuments, Under Police Guard,” The New York Times, April 24, 2017.

Don Boroughs, “Why South African Students Say the Statue of Rhodes Must Fall,” National Public Radio (NPR), March 28, 2015; Bernard M. Magubane, The Making of a Racist State: British Imperialism and the Union of South Africa, 1875–1910. (Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press, 1996).

Don Boroughs, “Why South African Students Say the Statue of Rhodes Must Fall.”

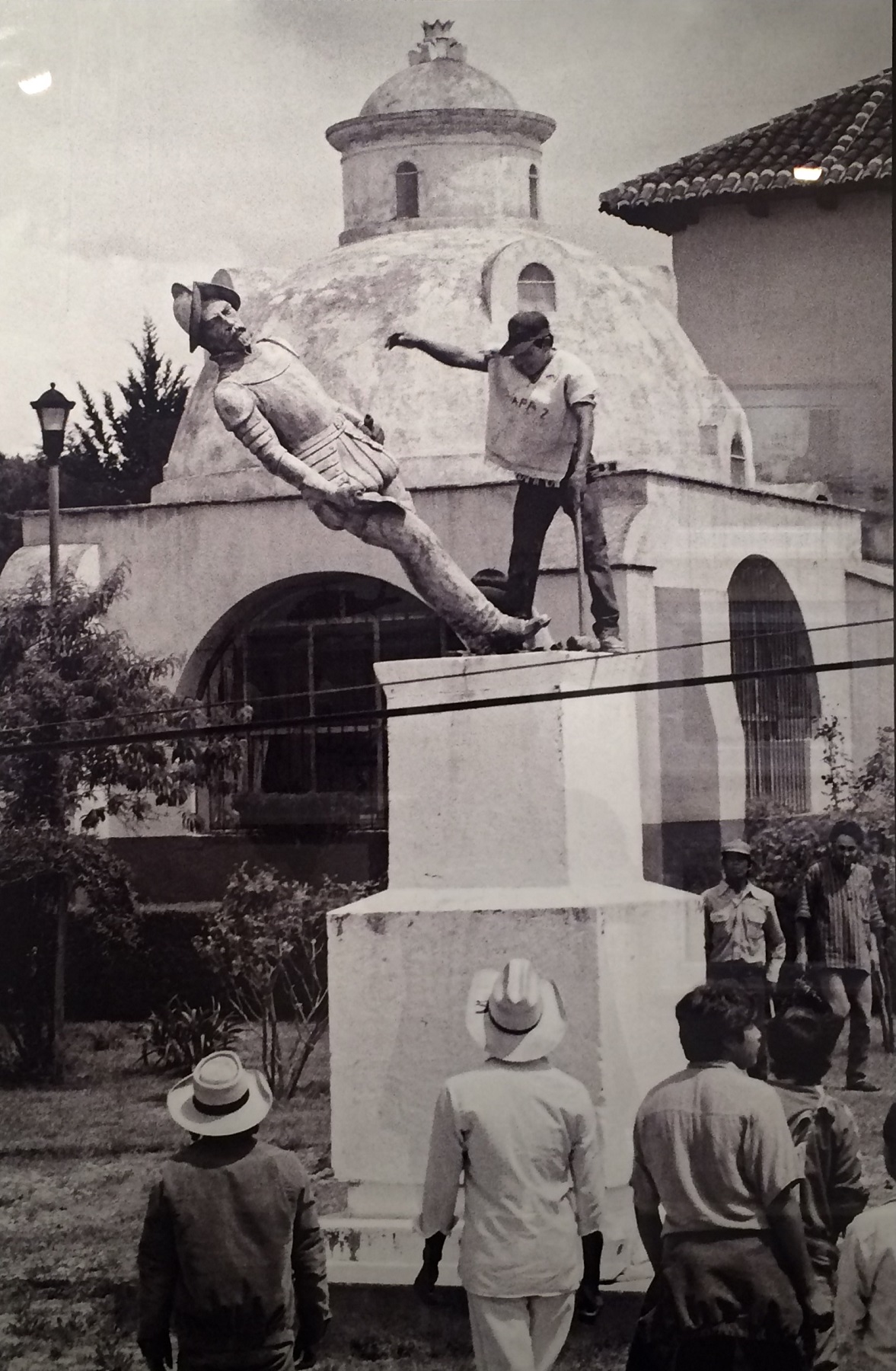

Thomson Gale, “Zapatista Rebellion” in Encyclopedia of Race and Racism, ed. Patrick L. Mason. (Macmillan Reference USA: 2008).

Anonymous, 500 Years of Indigenous Resistance (The Anarchist Library, 1992).

Max Greenwood, “Trump on Removing Confederate Statues: ‘They’re Trying to Take Away our Culture’” The Hill, August 22, 2017.

Ruth H. Hopkins (@RuthHHopkins), “Privilege is saving confederacy statues because they’re “historic” but bulldozing through ancient sacred sites and artifacts for pipelines.” Tweet, August 18, 2017. Accessed by the author on August 23, 2017.

Jimmy Tobias, “Trump’s day of doom for national monuments approaches,” The Guardian, August 20, 2017.

Sandra de la Loza, The Pocho Research Society Field Guide to LA: Monuments and Murals of Erased and Invisible Histories (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press: Los Angeles, 2011).

Maura Reilly, “Taking the Measure of Sexism: Facts, Figures, and Fixes” ARTnews, May 26, 2015.

Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, published 2015.

Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War president credited with abolishing the enslavement of African-Americans, ordered the execution of 38 Sioux prisoners on December 26, 1862, a mere five days before the Emancipation Proclamation was made public. Durant’s sculpture depicts the gallows and a full account about the work and the history it references can be read in: Sheila Dickinson, “’A Seed of Healing and Change’: Native Americans Respond to Sam Durant’s ‘Scaffold’,” ARTNews, June, 5, 2017.

A description of the performance may be found on the blog Another Righteous Transfer! exploring performance in the LA art scene, posted April 13, 2015.

Wikipedia’s list of Whitney Biennial Artists (1973-2017).

David W. Dunlap, “Long-Topples Statue of King George II to Ride Again, From a Brooklyn Studio,” The New York Times, October 20, 2016.

Comments

There are no coments available.