Issue 18: Of Passageways and Portals - Guatemala Quetzaltenango

Reading time: 8 minutes

06.08.2020

Writer and curator Diego Ventura Puac-Coyoy contrasts Mayan knowledge with the forthcoming and memory projected in Guatemala’s landscapes: where artist Alfredo Ceibal dreams of painting as a healing exercise.

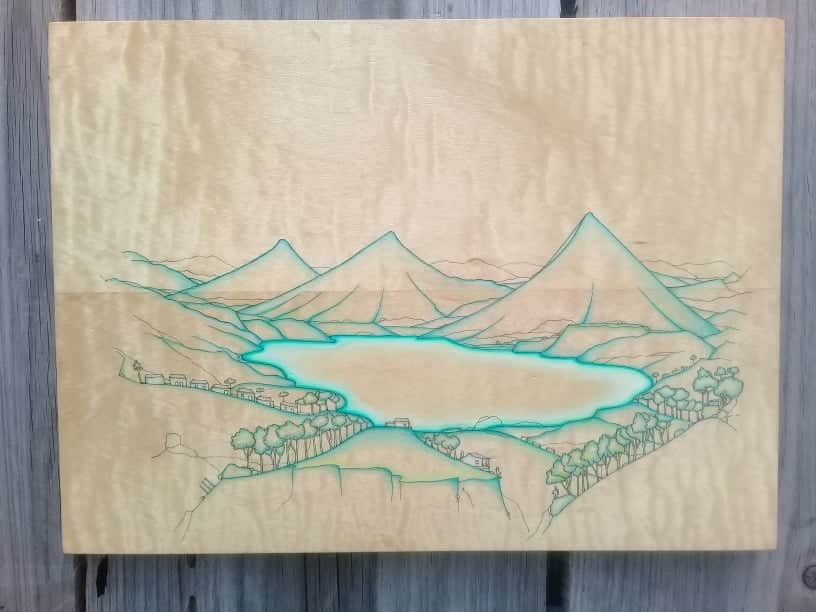

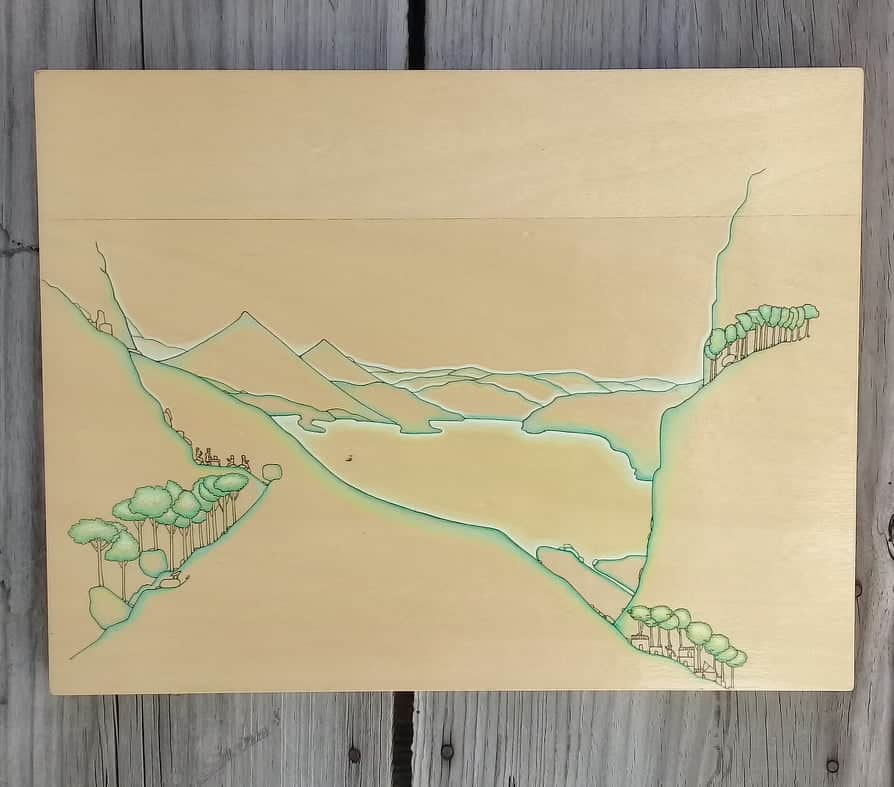

Alfredo Ceibal, de la serie Lagos de Cristal, 2018 - 2019. Acrílico y carbón sobre maderas preciosas; 40 x 50 cm. Imagen cortesía del artista, revista Polyester & 21ª Bienal de Arte Paiz

The children of fire, as well as the children of bats and the heirs of water,[1] have been taught to relentlessly seek the past. Sometimes through words, other times through rituals. Occasionally through reading the sky, and at times, through understanding the weavings that our mothers, grandmothers, and sisters wear on their bodies. We have found the past carved in stone. When they wanted to erase us, we found it in mass graves, hugging the earth, this earth, our earth.

We have also learned to live with all our deaths, to remember them, to honor them. Because it is a transcendental step to becoming a memory and becoming a spoken, enunciated path. All of life is a poetics linked to the earth: at birth, we explode like a budding güicoy flower,[2] those flowers that take over entire fields, joining their filaments to the earth as those that seek a way. When we die, they wrap us in a petate and return us to the earth to germinate and become a flower once again. And so the seed: from flower to fruit and from fruit to burial. Rituals are not just for the burial of humans, there are rituals in seed burials as well. A candle on the surface, liquid dripping, flowers, incense. You talk to her quietly, kneeling to the mother’s womb, so she remembers all of her children, all of those who are hungry and yearn to eat.

There was a time in which they stopped teaching us the earth’s knowledge. We began to go to school, to learn about numbers and the correct way of pronouncing things; that it is not haiga but haya and that the order of the factors does not change the product. They also taught us the names of the forefathers that brought us liberty and country. There, we learned that the invaders of the old continent brought civilization and that all our Gods, that received payment for a job well done, were pagan. Instead, they taught us about a punishing love and a venomous guilt, about submission and the sky-painted ceilings of churches that crumble when Kabrakan[3] walks.

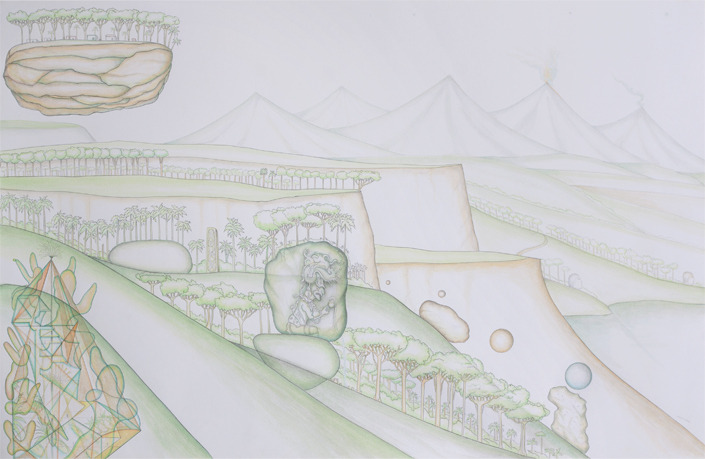

Alfredo Ceibal, Paisaje con estela, 2015. Técnica mixta sobre papel; 90 x 120 cm. Imagen cortesía del artista, revista Polyester & 21ª Bienal de Arte Paiz

Seeds and agriculture began to be associated with poverty, with scarcity. There are those who say that beans are the food of the poor. And all that earth, that was ours—and is still ours—was taken away, as well as its bounty. We began to die slowly, like when the orange groves know that their time has come and so they discard their tiny fruits. And thus is the life that we got: one between resistance and tears.

After, They Painted Us

There is a certain period in Guatemalan art history where the lives of indigenous communities became a leitmotiv for academic painters. That style began to develop at the end of the twentieth century and dominated the twentieth century. Even if said works have contributed to the documentary research of textile and landscape periods, their lasting effect is the folklorization of the country’s indigeneous life, as if it were a diorama or vignette, including its very own allegories that, after being demoted to craft (instead of deigned high art), would be appropriated for a process of modernization that erases us. Indigeneous communities see their actions restricted to forced labor, diversity quotas (but without a voice or vote), and the diffusion of a culture suited for commerce and tourism. In Guatemala, only a depoliticized “Indian”[4] can exist.

And Then We Got Tired

We could not continue working with the land that is rightfully ours because it was stolen. We could not be part of a country that is more landscape than nation. In these earthen paths, voices come together and travel through the mother’s womb together, looking to that section behind the hills from which our grandfathers watched the sunset and I do too. And our children will too. It is hard to understand freedom when you are far from the earth. We were born here, and the first thing that our eyes saw was life itself, dressed in green. We grew just like the cornfields, just like the trees. This is how they took care of us and this is how we should take care of them, although sometimes they do not let us.

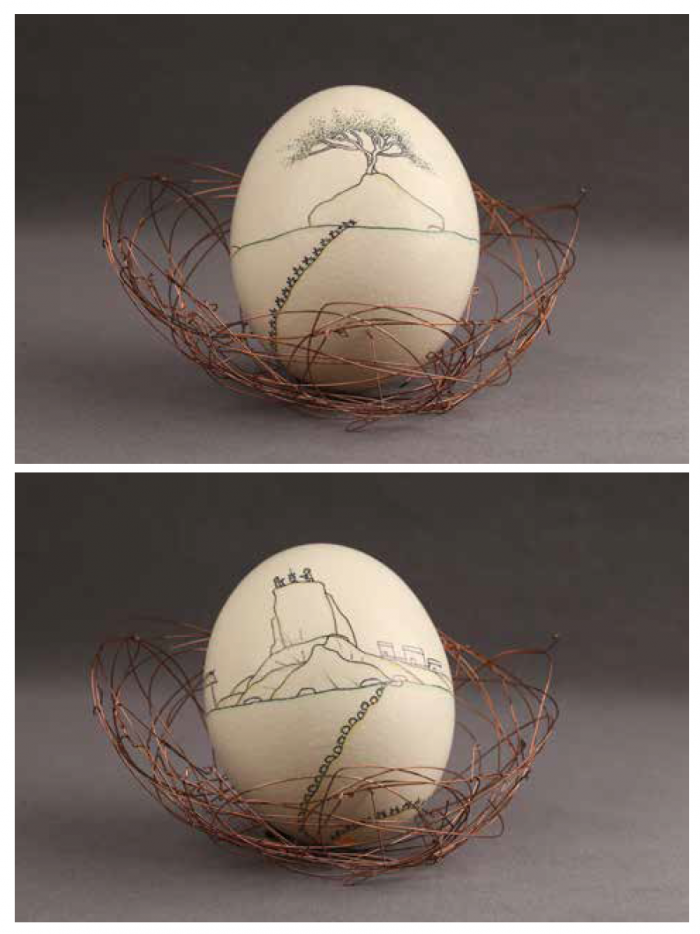

Alfredo Ceibal, Nido, 2017. Objeto intervenido. Parte de la subasta Juannio 2017. Imagen cortesía del artista

When we got tired, we demanded our land back; tenancy implies freedom and pay. By law, by history, by permanence. Land tenancy signifies the capacity to defend biodiversity, varied crops, natural balance, the native forest, concepts that are foreign for the new forms of colonization present in monocropping and deforestation. That is why, as indigenous communities, we are wanderers, we band together and resist, just as the 48 slums of Totonicapán and the indigenous municipalities that are allied with and supported by their communities. But there are other wanderers that, in this path, are word and breath.

One of those wanderers is Alfredo Ceibal. A prophet by profession, he carved the word in stone and told time—our time—in the shrines of the world: caves, rivers, lakes, and hills spellbound with life and death that visit and hug each other. In him exists a strong understanding of the fight for our land and the goodness of its fruits. His drawing always returns to the earth and germinates, it accompanies us, and extinguishes alongside us.

How to understand the coexistence of beauty and tragedy? Just by observing, noting, telling. Fire and ancestors already told us about human tragedy, when 400 young men died by Zipacná[5] and became stars, forming the Pleiades. Perhaps that is why Alfredo Ceibal draws his vision: a burial in mass graves, deep below, underground. Above, the hills that lovingly accept the corn that perpetuates our existence and our descendants. We’ve seen something similar in our recent history, in the Panzós massacre and in how contemporary history keeps showing us the plunder of the same area, in the Polochic valley.[6]

The Artist is By Profession a Prophet

Another dream: the stones that tell our history, receiving from the sky the same rain that our ancestors received. After, it returns to tell the sky’s heart what happens in the earth’s heart: Uk’ux’ Kaj, Uk’ux’ Ulew. Alfredo tells us all of these dreams through his drawings, with little color, because he knows that color belongs to huipiles, corn, fire.

Understanding and painting a landscape is quite simple. Living and traveling through it is a different story. One must understand that the landscape is beautiful from afar, as a spectator, but tough to work with and wander through. Because the sweet fruit of the earth comes from sweat and patience and life always comes back to it. Alfredo has seen it: the branch, the nest, the egg that is always brought back from the land to the land, from the earth to the breast, inseparable.

The word is also sacred. We come from the word. If our ancestors registered it through scrolls, Ceibal impregnates it in his imaginary, in his paper and in his poetics, through his Dialogues series.

What is not named does not exist. What is not named is forgotten. What is forgotten dies without being reborn. That is why, in the Dialogues series, we see that possibility of existing and persisting through memory.

For the Maya, the word poetry was the same word for honey, or sweet word, kaab tzij. What we name, love, war. The sky, the earth, the cornfield. The rain, the lightning, the tempest. Death.

Dialogues is a series that bases itself in memory. The oral history of our peoples, all of the information that saves us and unites us and distances us from the false official history. Thanks to the word, we can remember the first four men and women created, and through the word, we can call on the last ones that will be created. Through the word we learned the seed and the sowing, through it we name them and understand their worth. Through the enunciated and transmitted word, we know that memory is a certainty for our people, as certain as the memory of a native seed that perpetuates our existence, in resistance to the genetically modified seeds that forget and kill.

The Sky That We Will Remember

Because the sky’s promise is to always return….to return, to return. Because we want to go back to being flowers and we want to go back to seeing the world as the invention of a prophet like Alfredo Ceibal. Before, they told us that the Earth was fragile, that working the land was backwards. That it was better to study something serious, to go to the city, and that poetry was useless.

They also made us rationalize everything. That feelings are subjective and that data is truth. If this is true, the earth is actually the science of memory, emotions are fuel and fire for memory. When in community, one builds history through remembering, through tears, through love. That is why poetry, the word, and memory are reason and knowledge. From there, we are able to decolonize the written and unlearn the memorized. In that instant we learn to see the old world and the future: we read the sky, the stars, and the weavings of the huipiles. The Aj’quij reads blood and tzite’. The human reads art and the artist is poet is prophet and that is where we see it clearly: the understanding that Alfredo Ceibal has of natural cicles and of the world as an integral living organism is so captivating that without his work, we would be missing a piece of the sky.

—

This text was translated from Spanish to English by Isabel Ruíz.

According to our origin story, the Maya K’iche are children of fire. The Kaqchikels are children of the bat and the Tz’utujiles heirs of water.

Zucchini

Kabrakan, responsible for the earthquakes according to the K’iche’ holy book Popol Wuj.

The Indian is a social construction, a stereotype configured by the racist and classist state of what a Mayan descendant should and should not be. The term is used in anthropology and social sciences.

The one that moves the hills and causes landslides. Kabrakan’s brother according to the Popol Wuj.

Maya Q’eqchi territory that has been robbed by the Guatemalan state, assassinating the original owners of the lands and community leaders to cede mining and monoculture concessions.

Comments

There are no coments available.