05.05.2022

In a poetic account of a tour through the halls of MAC Panama, Maia Alfaro reflects on two exhibitions that strain the colonial space-time and offers us a tender and profound look at the resistances in their genealogy.

I visited the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Panamá on a Sunday, minutes before opening time. The door was already open, but it felt like stepping out of the known and accepted temporality. Although the image was still off, I played the Lizette Nin video headphones without thinking, almost as if to camouflage myself and, by some miracle, the audio had stayed on from the day before. I was enveloped by the daily intimacy of the dialogue between women and my gaze traced the braids in Nin’s drawings, as if they were routes to flee even further from time.

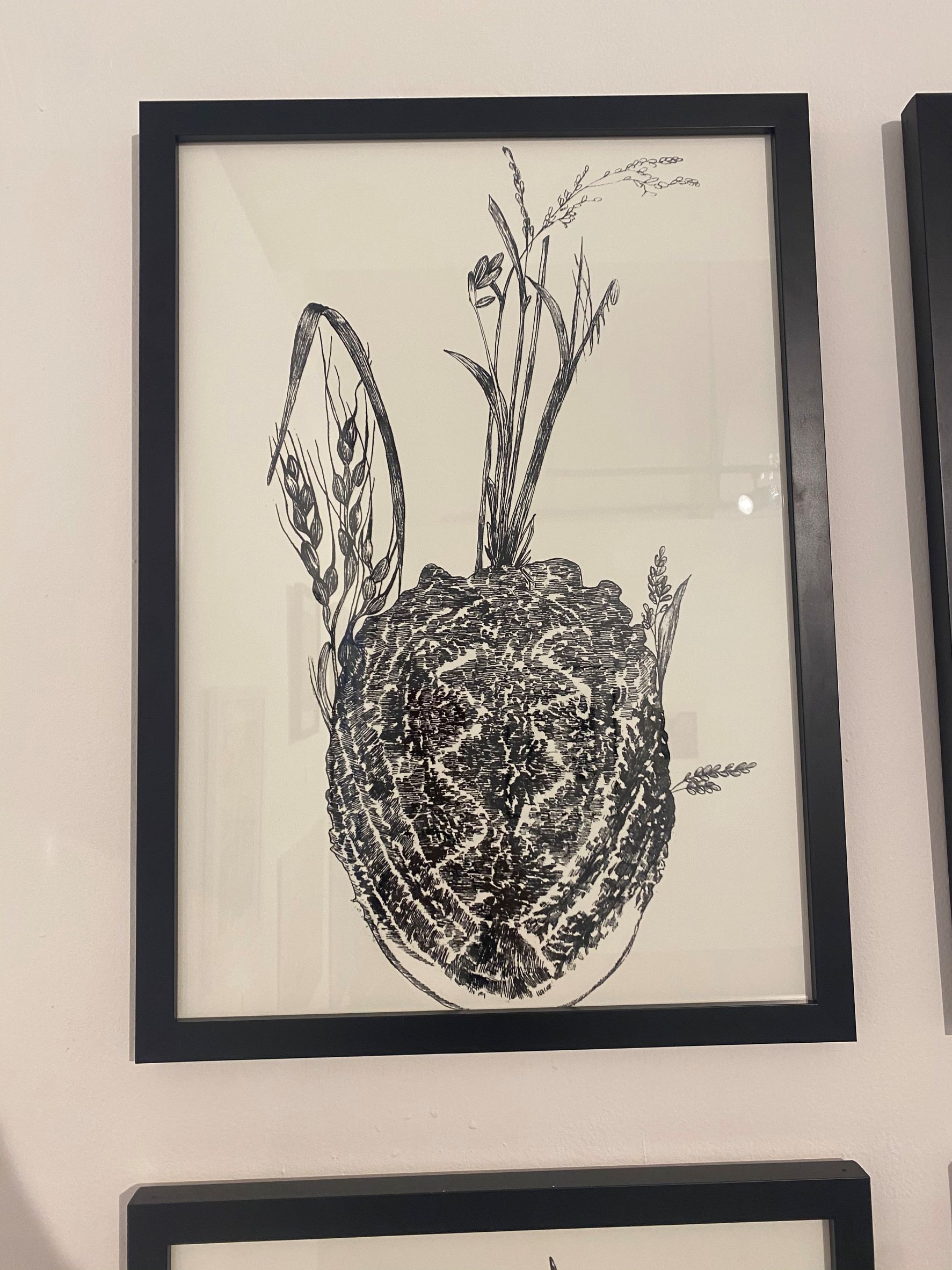

The exhibition Keeping Seeds in the Hair, conceived by Juan Canela, the MAC’s new curator, and curated together with Judith Corro, Cristina López Urriola, Andrea C. Miranda Pestana and Mana Pinto, honors the physical and feminine labor of witnessing and processing life, with its wounds and beauties, its mourning and its potential. The resonance of Margarita Monsalve’s engraving, De los gritos, is not that of a scream, but of a cry tenderly sown in a garden.

In José Luis Alexanco’s Hombre y mujer rezándose a sí mismos, the figures yield to their own primordiality; like seeds hidden in maroon hair, waiting, patiently, to burst into life. Somewhat like this, huddled in the shadows and caressed by the natural light that barely filtered through the windows, I contemplated Monica Kupfer’s etching Caricias II. In the limited enclosure of the museum, the walls were not yet white and neither was the paper of the work; as if white did not exist; only shadows without fixed demarcations, insinuating an obvious and ambiguous movement at the same time.

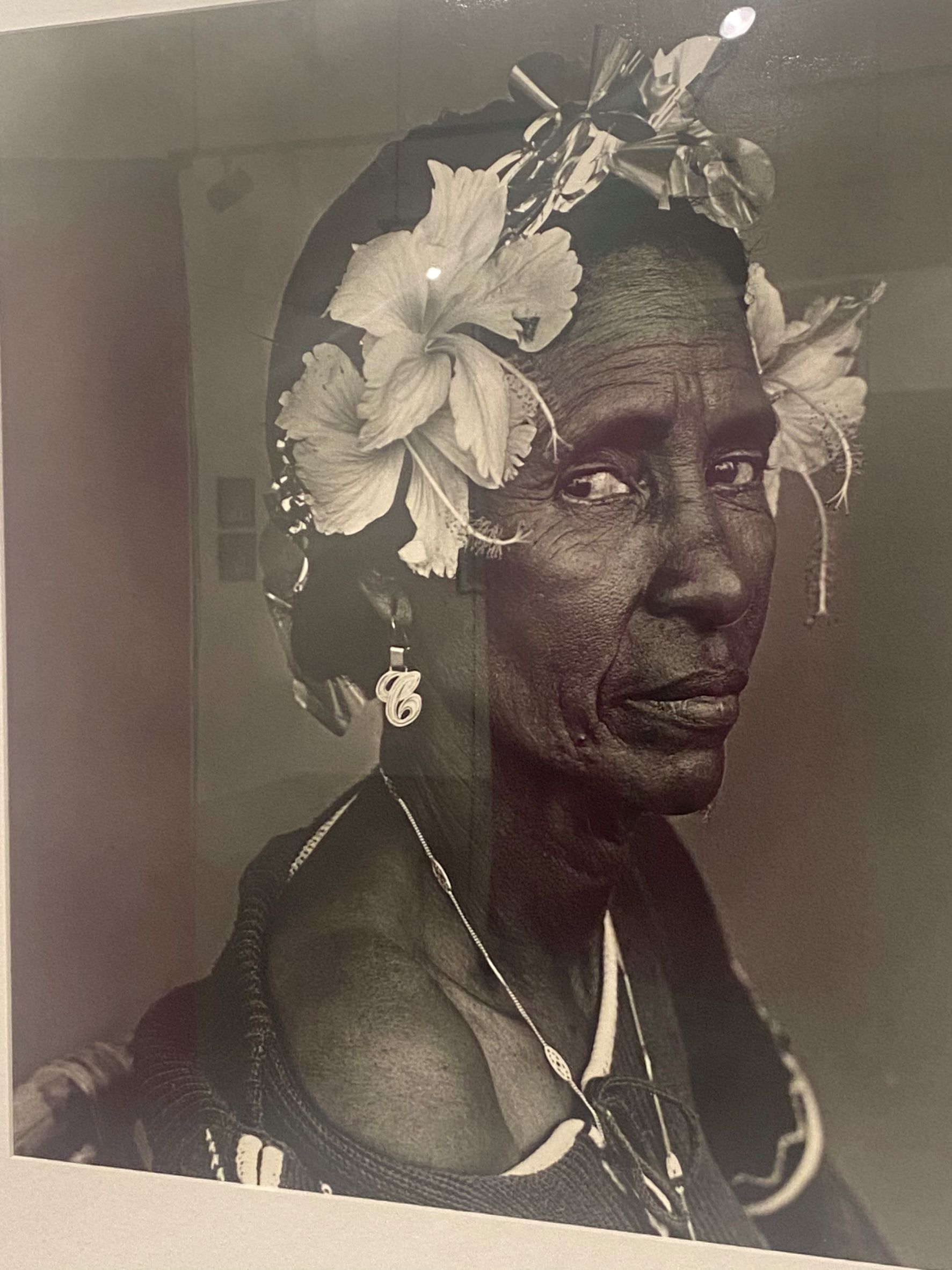

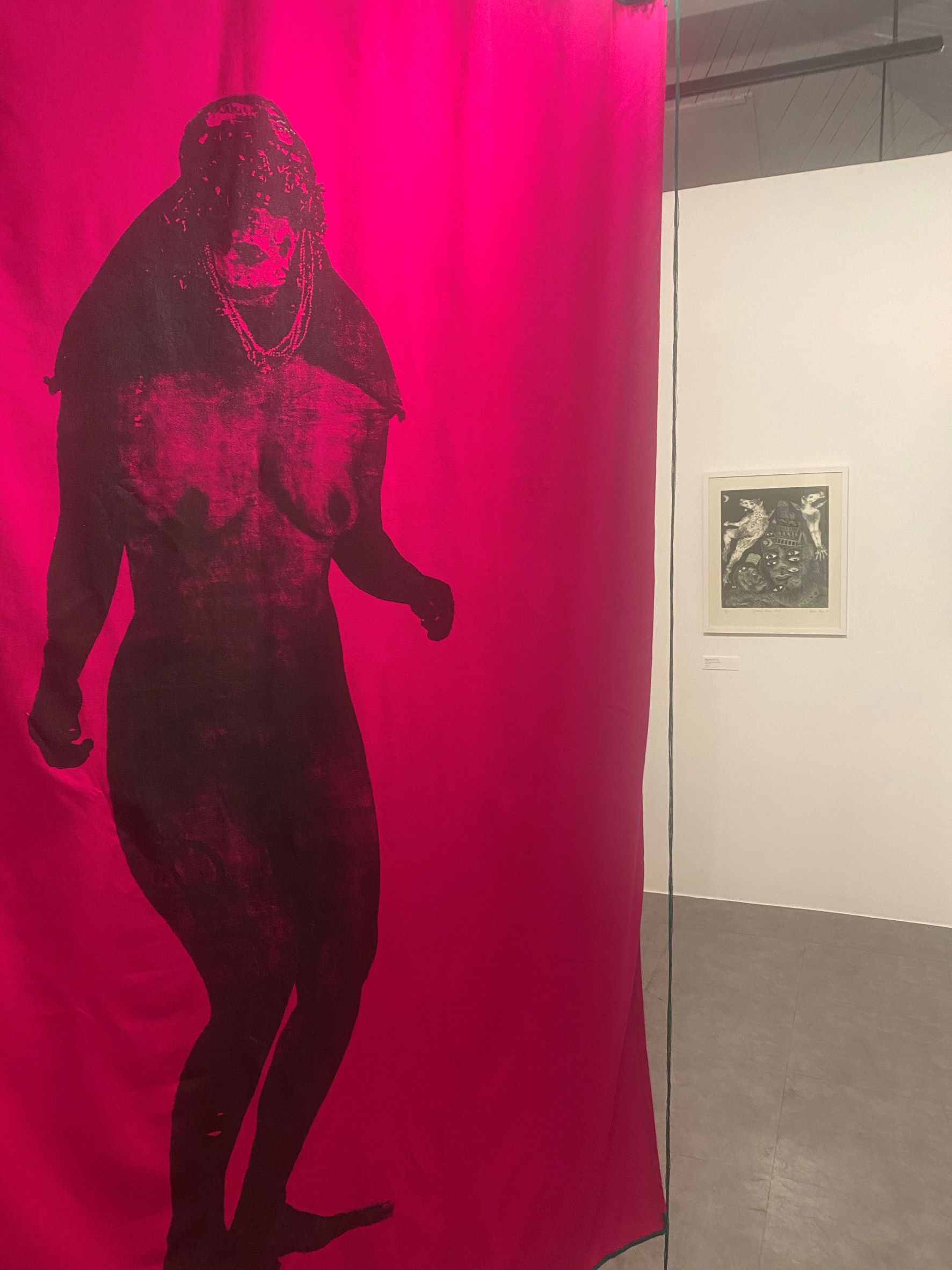

The lights were turned on and a myriad of diverse lines began to define themselves, sharp, thick or vibrant-fingerprints of Risseth Yangüez, waves of potentiality of an engraving by Juan Downey, depicting Catalina, Queen of the Congos-tangling, combing, crossing and interweaving, visibly and invisibly. From among them emanate purples, puffs of light blues, and floods of intense pinks, like those of Julieth Morales’ looms that,marked with the image of her body at once naked and masked, permeate the room with generations of death and new life.

This and other works in the collective exhibition examine the fusion between the colonized and the indigenous and Afro-descendant ancestry. The Emberá textiles exhibited by Andrea Lino Machi of Caizamo reveal a Made in Japan label; synthetic hair surrounds, like a halo, the women braiding their hair in Nin’s video; and the waves of the sea in Achu Kantule’s painting point to their center. The confusion of carrying the legacy of the system is also expressed in the figures of Ruben Maya’s Cosmic Duality, whose faces sprout symbols, buildings and many eyes, turning them into something monstrous. But how can we speak of the monstrous in a system that has decapitated words and turned their corpses inside out, spilling blood all over communication?

The following Sunday I returned to the museum. I went in a big pajama dress and with one of my favorite cups to hold my machine-brewed coffee. I sat down to watch the videos installed on the sides of El descanso, the little house built at the core of the exhibition La pisada del ñandú (o cómo transformamos los silencios), curated by the artistic team Río Paraná, composed of Duen Sacchi and Mag de Santo, and installed on the entire second floor of the MAC. “I don’t share the idea that we are discriminated against,” says one of the protagonists of Entrenosotro, a documentary by Sebastián Molina Merajver, throughout which I kept laughing and shedding tears over my coffee. The daily life of trans shines with a lightness that bounces my gaze in infinite directions until it takes me out of that mutilating certainty of colonial time-space. Protected from the air conditioning by a Bob Marley coat I borrowed from the closet of El descanso, I let myself be transformed, just as the institutional space of the museum is letting itself be transformed.

Expanding and at the same time simplifying what LGBTQ anti-coloniality can be, in the video Ese’ja, Pancho Casas, in a ritual of return or collapse of time, undoes his transvestism to become an indigenous person. It is as if to say that he has had enough of the transvestite spectacle that mocks colonized gazes through precise combinations of natural and synthetic elements, and, in a sexual dazzle, transmutes those same gazes. But the civilized world of museums and videos remains an integral part of the work, in form and content. In it we see how the long lenses of the cameras burst into the Amazonian community with their clinical and voyeuristic gazes that capture and denaturalize what they touch.

In such a case, perhaps a ritual led by a Machi Weye, a non-binary shamanic figure, like the ones that thrived in indigenous communities around the world before being violently erased, would do well, since the colonial system cannot exist at the same time as that talismanic fluidity, and needs to remove them in order to carry out its extractive and controlling mission. In his audiovisual piece Nunca seré un weye, Seba Cafulqueo laments the impossibility of assuming that role and at the same time participates in the process of regenerating it, of nurturing its sacred potency. Decolonizing, as this exhibition proposes, involves not only undoing what has happened but also witnessing and honoring the connective threads of blood and light that are the result of the brutal struggle, of magical survival. For example, including Theodor de Bry’s engravings, which graphically depict the murder of indigenous non-binaries, is an act of transformative bravery; but it also, with its candles and flowers, alludes to the aesthetics of Latin Christianity that centers its idolatry on the violence of crucifixion. The adjoining image of the Virgin of the Guacas, a document of the performance of a trans artist (Giussepe Campuzzano) dressed as the Virgin, places this attempt more firmly within the context of the religion imposed by the colonizers.

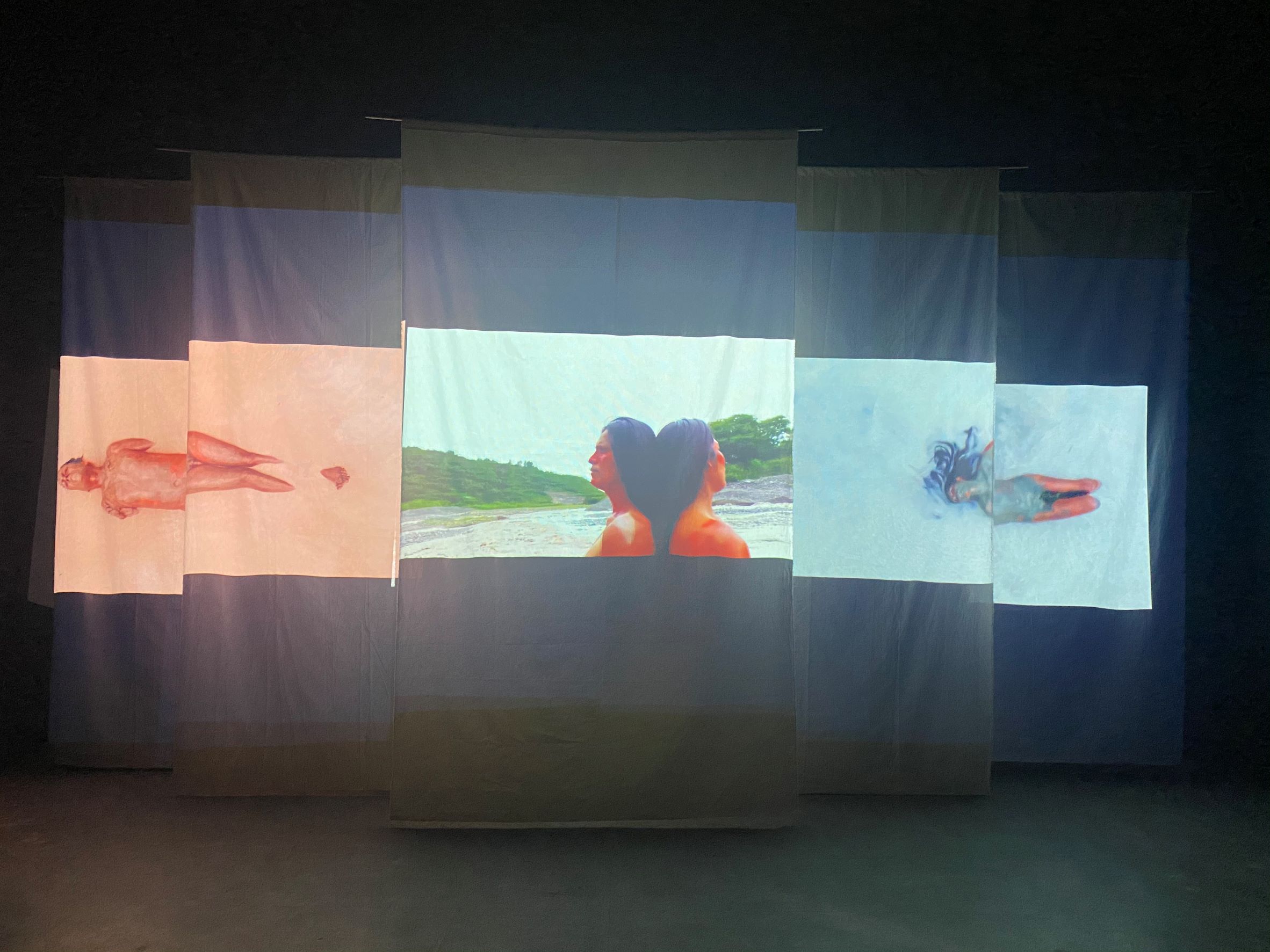

The poetry and plenitude of this exhibition calls for close and deep attention. Pause, for example, in front of Rio Parana’s video installation A Thousand Events Lost So Far, in which two trans sisters join the slow, muddy flow of a great river. The three-channel video absorbs the visual panorama with the communion of their indigenous bodies, one with the other and, at the same time, with the land.

Both exhibitions explore and honor the forms of gentle self-care or drastic self-expansion through which oppressed communities survive, deepening and maintaining their connection to nature. They play as new frost and devoutly rediscover ancestral maps. Anything but surrendering to the imposing ubiquity of the colonizing system. Upon returning home that same Sunday, and feeling a torrential rain fall, I went out to the patio to lie down in the mud to cry.

Comments

There are no coments available.