12.05.2016

by Eduardo Abaroa, Mexico City

April 15, 2016 – April 16, 2016

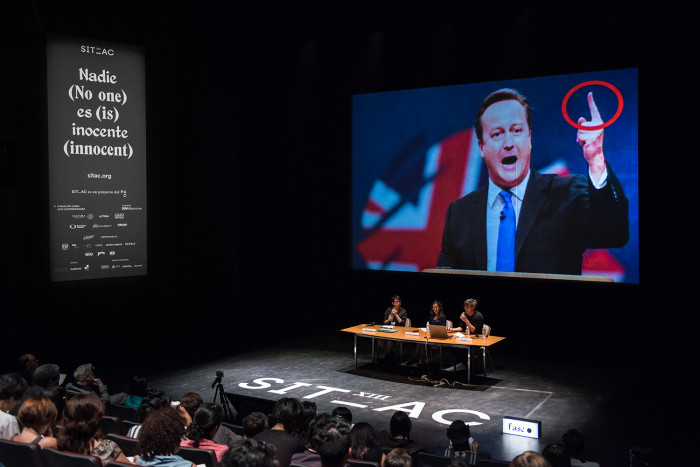

SITAC: THE THIRTEENTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL THEORY SYMPOSIUM ON CONTEMPORARY ART. MEXICO CITY, 2016

April 2016 saw realization of Phase I at SITAC XIII, entitled “Nadie es inocente” (“No One Is Innocent”) a symposium given over to discussions of “the limits between the public and the private; the State’s role in producing and distributing contemporary creation; the weakening of borders that separate commercial from cultural interests [and] the role of the mass media in public perceptions of artistic practice.”

Almost all previous SITAC editions have contained a dose of reflection on these issues. But this time around the organizational team seems set on going beyond the theoretical vocation that gave rise to the event and now will attempt “to propose collective solutions.”

The plan is to carry out this first symposium phase, followed by a second, “NODOS” (i.e., “nodes”) that “will take place in the form of various activities (seminars, public discussions, video cycles, etc.) between May and August.” Ultimately there will be a final conferences session that will seek to sum up what was achieved over the course of the entire process.

The first phase is what we, the approximately 600 (plus another thousand online) who attended these two sessions, witnessed. It was smart to begin the event with Boris Groys, whose now canonical texts at once shred and lend new life to the institutions that present today’s art to the public. Naturally it’s hard to identify any concrete signpost that would lead to action, from among his achievements—above all because their description of first-world art does not so easily dovetail with the Mexican context—but that said, his ideas can serve as a good point of departure. In his 2003 essay, “The Museum in the Age of Mass Media,” Groys articulates one of the solidest-ever defenses for the existence of museums:

“…given our current cultural climate, the museum is practically the only place where we can actually step back from our own present and compare it with other eras. In these terms, the museum is irreplaceable because it is particularly well suited to critically analyze and challenge the claims of the media-driven zeitgeist.”(1)

In a SITAC conversation with Magali Arriola and Nina Möntmann, Groys described how nation-states lost interest in self-representation through museums. He also pointed to a change in recent years: now that museums must have a constant internet presence via social media, to attract patrons, they have transformed from spaces of cultural collecting where “nothing happens” to places where things are always taking place—symposia, events, etc.—and now are stage sets where Hollywood celebrities and millionaires are popping up. Groys expressed optimism despite everything.

Writer Rafael Lemus moderated the next round-table and delivered an excellent account of the disaster we lived through in Mexico during the twenty-seven-year run of the recently suspended Mexican cultural institute known as Conaculta. George Yúdice spoke of the comeback some of the most pernicious features of neo-liberalism have made in a number of Latin American nations as he lamented the long road one must tread to effectively foment cultural diversity. He wrapped up his contribution by underlining how nation states have ceded their sovereignty to leading technology corporations such as Google, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft and Apple. Chilean anthropologist Claudio Lomnitz, somewhat confused about his role at this event, held forth on the absence of viable narratives that can spearhead change in Mexico, a rather wide-ranging problem that could be the theme of an entire symposium.

Art critic María Minera organized a “mixed-crowd” roundtable with five participants that sought to subject “the Mexican cultural apparatus to examination” and discuss new culture-related legislative reforms in Mexico. Carlos Bravo Regidor, Alejandro Hernández, Déborah Holtz, Luis Vargas Santiago and Heriberto Yépez took up the issue based on questions from the organizer. The debate grew tense soon enough, thanks to the second set of remarks, by Mexican writer Heriberto Yépez, who in his characteristic style declared that the newly reformed institution is in fact the Culture Ministry of a dictatorship, at the same time he mentioned the privileged and convenient place the intellectual class occupies in what he called “the PRI [ruling political party]’s neoliberal dictatorship.” As if responding to Minera, who in her introduction wondered what to do to make sure “letters to Santa Claus” are received, Yépez concluded that maybe by asking these questions about State support, intellectuals were looking for some of their own soft power within a “soft dictatorship” at the same time professors, students, journalists, activists, etc., suffer the “iron fist” violence of authoritarian rule.

There were confused reactions from some of the panelists. Trilce Ediciones director Déborah Holtz was one of the few that stayed focused on the issue and openly defended the new institution’s potential by arguing it will allow for more participation on the part of cultural actors alongside less bureaucratic interference. Other matters were mentioned on the panel, including culture and its presumption as a human right; the lack of legitimacy with regard to an “inside” and an “outside” in culture (or the State); problems within the grants and fellowships system; what it means to say “State” after the notorious disappearance of 43 Mexican students at Ayotzinapa; the act of “settling in and resisting,” etc. But Yépez was not to be assuaged. Sensing the atmosphere had grown strained, he still sought to go deeper:

“…the body that forms from our position as intellectuals in this society evinces a certain trust that institutions will respond, but this is a fiction created from technologies of the self, i.e., the technology of the self that calls itself institutional revolutionary.”

The statement led to additional uproar. From the audience, curator Helena Chávez, who has worked in major Mexican museums like MUAC, challenged eclectically-minded Tijuana-born Yépez by saying it was not possible to renounce exercising resistance from within institutions and that this could be complemented by collective action at the institution’s margins. “The Escuelita Zapatista is a great initiative, but we cannot turn our backs on the National Autonomous University, the National Polytechnic Institute or public education.”

Yépez’s intervention was stimulating no matter how you look at it. But his analysis, cut short by a lack of allotted time, went beyond the mere jeremiad some discussion participants perceived.

Minera closed the panel nervously: perhaps this was not the forum for discussing the legislation’s technical aspects; including so many participants on the panel was unfair to all involved. A conference just with Yépez or a less “loaded” panel might have been more effective.

The afternoon session, moderated by promoter Osvaldo Sánchez, was notable for an intervention on the part of the Chilean-born New York-based critic Christian Viveros Fauné. His speech against the rise of speculative capital in art contained a heavy dose of information on “The Panama Papers” and Viveros spoke of an assuredly destructive and criminal market that had become “the financial world’s favorite game.” As a counterpart to this absurd situation, Viveros made mention of projects by the Danish group known as Superflex, African-American artist Theaster Gates or “art-tivist” Tania Bruguera, who have used “market values to present values of opposition.”

Participation on the part of Dolores Béistegui, who currently directs the Papalote children’s museum, was a perfect example of the corporate outlook. You have to hear this very carefully. Understanding how large-scale museums operate and what objectives are posited as part of the mercantilist logic are essential to generating urgently needed alternatives to that model.

The second day of panels was dedicated to “The Production of Art Value.” The discussion took on a special richness with interventions from Brenda Caro and the day’s coordinator, Pilar Villela. US writer Marina Vischmidt referred to the type of art that Viveros Fauné viewed the previous afternoon as an alternative to art’s hyper-capitalization. For Vischmidt, these practices demand “(the use of art) for a socially progressive, activist notion of use, without opening up how we might understand use in a society which is organized around something totally different from the socially useful, that is, organized around exchange value and profit. Such arguments can unfortunately tend to consolidate the imperialism of the social instance of art at a higher and more insidious level.”(2)

As part of the same panel, Danish sociologist Pascal Gielen defined the term “culture” as that which lends meaning to people’s lives. By reminding us that both Marxism as well as neoliberalism consider economics to be society’s sub-structure or base, Gielen, somewhat ingenuously, proposes situating culture as the base of society. In line with Chantal Mouffe, Gielen defined so-called “commonism” as a deliberative democracy where in pursuit of an ideal harmony there exists a constant struggle for different individual and subjective positions, among which art is a privileged vehicle. Such “commonism” brought to mind the commonality that Zapotec writer, activist and musician Jaime Martínez Luna put forth at the last SITAC in Oaxaca, a very different analysis since in it, the most important element is the common good, duty and harmony with the earth.

The second panel that day was a debate between two Englishmen, Dave Beech and Stewart Martin, who respectively argued for and against the idea of the artwork as a special kind of merchandise in economic terms. This critical concern, to which other panelists referred, gave rise to the event’s only truly theoretical debate.

As part of the last panel, Sandra Sánchez and Alejandro Gómez Arias offered up a magnificent survival portrait of young people in the Mexico City art world. Based on very personal viewpoints, each presented his or her ideas and confusions regarding what the local art scene is, pondering the economic viability of their practices if they seek not to deactivate their critical potential. To conclude, Daniel Aguilar Ruvalcaba read an admirable and entertaining text about a “piratical adoption” of Damien Hirst’s skull image for a set of narcocorrido songs.

Many wonder if the conference format is still appropriate and useful. For me, SITAC continues to be a privileged forum for debate and a worthwhile pedagogical tool beyond whether it does or does not reach its stated goals. Despite a few missteps, listening in carefully on line is well worth the time and trouble.

Notes:

(1) Boris Groys, The Museum in the Age of Mass Media, 2003, Manifesta: Journal of Contemporary Curatorship #1: The Revenge of the White Cube, Manifesta International Foundation, Amsterdam, Silvana Editoriale, Milan, p.47.

(2) Cita de Marina en inglés, min 38/56:

…claims it (the use of art) for a socially progressive, activist notion of use, without opening up how we might understand use in a society which is organized around something totally different from the socially useful, that is, organized around the exchange value and profit. Such arguments can unfortunately tend to consolidate the Imperialism of the social instance of art at a higher and more insidious level…

The entire Fase 1 of the International Symposium on Contemporary Art XIII can be found in three parts at:

Comments

There are no coments available.