24.01.2019

By Matthew Stromberg

Los Angeles, California, USA

September 29, 2018 – February 16, 2019

As right-wing movements take hold across the globe—from the US to Brazil to Europe—liberal progressives are confronted with an existential crisis. Feeling betrayed and disillusioned with the promises of the institutional Left, they must search for new forms of resistance to cultural conservatism, xenophobia, and destructive capitalist ideologies that are enacting real violence upon already marginalized communities. Instead of completely starting over, however, there is a rich legacy of revolutionary and subversive movements upon which to build.

Regeneración: Three Generations of Revolutionary Ideology at the Vincent Price Art Museum (VPAM) focuses on three examples of radical thought and action across the 20th century, each adopting the term regeneración. The first is the political newspaper published in Los Angeles by the Mexican anarchist Flores Magón brothers from 1900-1918; the second is the journal Regeneración produced in the early 70s that was a vital mouthpiece for the Chicano Movement; and the third is the experimental community-based art and performance space Regeneración / Popular Resource Center of Highland Park, which ran from 1993-99. Although each of these was geographically active in overlapping and neighboring areas of LA’s downtown and Eastside, the show traces a broad network of both Mexican and Chicano cultural resistance and political activism that spanned two counties.

One of the exhibition’s main challenges is how to capture movements that were based more in radical belief, activism, and community than aesthetic objects. Instead of letting single works of art tell these stories, Regeneración relies on a diverse range of archival material, ephemera, publications, performance documentation, video, and photography. (Fittingly there is a robust film and performance program accompanying the exhibition, including a two-day symposium held last Fall.) This allows each version of Regeneración to be represented in the forms of media that best suit it, however, the results for the viewer can be varied.

This is the case with the first section focused on the Flores Magón brothers—Ricardo, Enrique, and Jesus—radical Mexican activists and publishers who began their career of political dissent protesting the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz. In 1900, they founded Regeneración, the official newspaper of the Mexican Liberal Party or PLM, and in 1904 they fled their home country after their writing was banned, eventually settling in Los Angeles, where they continued publishing in exile. The paper’s first LA office was on East 4thstreet on the edge of today’s Little Tokyo before moving to the Flores Magóns’ Edendale compound, on the border of present-day Silverlake / Echo Park.

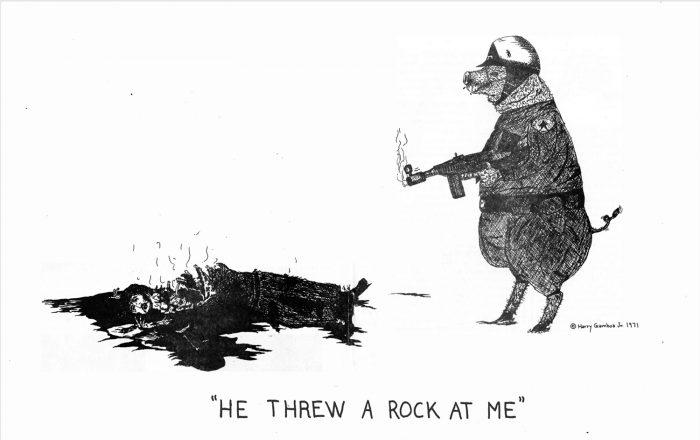

The paper was focused not only on covering the revolution raging in Mexico, but also advocating for social justice and labor rights. Its slogan, “Escrito por trabajadores y para trabajadores” (written by workers, for workers) is an excellent reflection of this mission. The exhibition reproduces a series of cartoons that capture the paper’s anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist stance. Other pieces of ephemera such as photographs, letters, and newspaper reproductions flesh out this history, culminating in a series of mugshots of Ricardo Flores Magón, who was arrested several times for his incendiary rhetoric and attacks on America’s involvement in Mexico. In 1918 he was arrested for sedition for publishing an anti-war manifesto and was sent to Leavenworth Penitentiary in Kansas, where he would die four years later.

Poring over these historical documents, a certain kind of informational fatigue can set in. The history is fascinating, but a conventional museum display is an especially difficult venue in which to encounter it. The curators have included some contemporary artwork, such as Ruben Ortiz Torres’ Tierra y Libertad (2013), which reproduces the anarchist slogan—introduced to the Mexican Revolution by the Flores Magón brothers—in thermosensitive paint, however it seems like an attempt to enliven the archival material that doesn’t quite succeed.

Approximately fifty years later, another journal would take the moniker Regeneración in a deliberate reference to the earlier generation’s revolutionary spirit. This one, founded by activist Francisca Flores, sprung out of the Chicano Civil Rights Movement of the late 60s and covered politics, poetry, and art, often with a feminist bent. It became a collaborative vehicle for the Chicano art collective ASCO, one of whose members, Harry Gamboa Jr. was a lead organizer during the 1968 student walkouts in East LA and was the journal’s second editor. VPAM has on view several issues of the magazine, the covers of which illustrate raw DIY energy. In one, a drawing of Cuauhtémoc graces the cover, connecting the struggles of Latinx communities in Los Angeles with a centuries-old form of indigenous resistance. Another photo collage by ASCO member Gronk intersperses images of the group with close-ups of Ricardo Flores Magón’s piercing eyes, making clear their claim to his ideological lineage.

In addition to their publishing activity, ASCO staged street performances, such as First Supper (1974) in which they set up a dinner party on a median in Whittier Boulevard, on a site where police had opened fire on a crowd three years earlier. VPAM has included photo documentation of this performance alongside photos from a performance almost 25 years later at the National Day of Protest Against the Massacre in Chiapas, which pictured Patricia Valencia, Felicia Montes, and Martina Estrada Melendez, artists connected to the Popular Resource Center of Highland Park. There are moments like these in the show—another one tracks a line of feminist resistance—where time collapses and the synergies between the different movements shine through.

The last section comes with its own challenges, as it focuses on a malleable community space in Northeast LA that was more oriented towards performance and ephemerality than static objects. Founded by musicians Rudy Ramirez of Aztlan Underground and Zach de la Rocha of Rage Against the Machine, the Popular Resource Center began as a space for political study but developed into a cultural and artistic center that attracted a diverse group of artists, musicians, and organizers. Their creative outrage was directed at the turmoil both at home and abroad. LA was still reeling from the 92 LA Uprising, while anti-immigrant measures like Proposition 187 were being passed, while in Mexico, the Zapatistas began their own uprising against the Mexican government in 1994. [1] Meanwhile the passage of NAFTA was ushering in a new era of economic neoliberalism.

The VPAM show attempts to convey something of the Center’s vital energy, though one gets the impression that you kind of had to be there. They have recreated the booth from their pirate radio station, Radio Clandestino—“Culture, New & Ideas Corporate America Doesn’t Want You to Know”—which broadcasts every Saturday from the museum, while videos of performances from bands associated with the space play on a wall nearby. Flyers, photos, drawings, and videos capture the range of activities, from actions of political solidarity with the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN,) to avant-garde performances by Guillermo Gomez-Peña and feminist art collective Mujeres de Maíz, to drawings by Raul Baltazar, surrealist sketches, that pick up on the rawness of ASCO’s magazine covers.

Regeneración is an incredibly ambitious show, and packs a great deal into a fairly compact gallery, trying to strike a balance between breadth and depth that it doesn’t always pull off. At moments, it seems like a book would be a more appropriate medium for engaging with the material, and fortunately, VPAM has produced a slim, but comprehensive catalog. The hundred-year-old photos and cartoons find a more welcome home between the utilitarian chipboard covers than locked behind a glass display case. Through the publication, one has the luxury of flipping between eras, comparing different expressions of radicality, and mimicking the experience of reading an issue of the magazine Regeneración. And for historical context on the images, several insightful essays fill in the gaps in more depth than could be gleaned from an exhibition label.

There is something deadening about the presentation of the archives in a museum setting, draining the blood from them, which is countered by the intimate interaction with the printed page or the drama of live performance. To its credit, VPAM has augmented the proper exhibition with both of these, which should be considered just as much a part of the experience of Regeneración as the show itself.

In a most serendipitous correspondence, the catalog is printed in Mexico City at La Casa de El Hijo del Ahuizote, a space of Diego Flores Magón, Enrique’s great-grandson. This is the same building where the first Regeneración was published, which is now a print shop and archive run by Diego, bringing the border-hopping networks of cultural resistance full circle.

—

[1] Significantly, the Zapatistas were influenced by elements of the Flores Magón brothers’ magonismo.

Significantly, the Zapatistas were influenced by elements of the Flores Magón brothers’ magonismo.

Comments

There are no coments available.