Reading time: 10 minutes

02.08.2020

Galería Nora Fisch, Buenos Aires, Argentina

July 30, 2020 – August 2, 2020

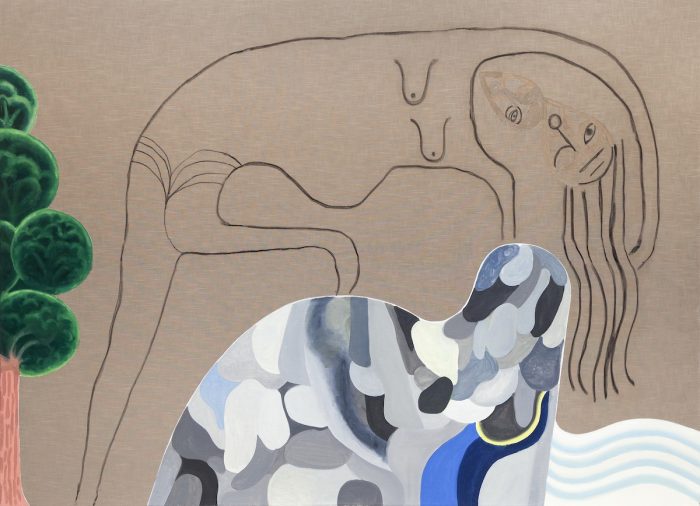

Gods and Peacocks

Just as for the Mayans the past and the hereafter were engulfed by a single concept,[1] each work in this cycle of paintings by Juan Tessi—works he has been making for a decade—bears its origin myth and its prophecy. Tessi’s approach—unlike European modernism’s—is not linear or monotheistic. This body of work does not grow by feeding off the fuel of the enemy, as Latin American anthropophagy threatened to do. Rather than unbury the past or gobble the other up, Tessi adds to his pantheon an array of simultaneous gods. He assimilates, just like the Mesoamerican communities that brought the deities of the defeated into their Olympus in order to increase their own might. For our artist, a thing announces what it is not only to prove otherwise then and there: a political form of creating, especially when the aim is to engender a new species.

Tessi’s painting leaps through times and forms from one painting to the next or even in the same work, with the faith conferred by the ethic of an inclusive pantheon. His art forms part of its region’s anthropophagic genealogy, but as one god among many. Tessi is as much a vaudeville-possessed peacock as he is an elegant North American lady with endless poetic imagination or an unshaven Latin American painter with age-old intuition. A sort of interspecies pictorial prophet, part medium, part bolero, part high tea. The god that Tessi and his work embody is not what matters, what does—at least for his practice—is to challenge the limits of painting and the closure of language. That’s why his work expands the canvas and materials, why it undertakes so many gestures and lets itself be jostled and intervened to merge into the context and posit suspended narratives. His methodology consists of incorporating to challenge oneself, to challenge what one is—to be oneself and also to be, not only to gobble up, the other.

In Azteca ritual, once the enemy had been captured he was treated like a god: he was well fed and elegantly clad, then sacrificed and skinned so that the shaman could put that skin on his own.[2] To embody the divine meant to be in the other’s skin. But the Aztec also cross-dressed: he painted his body and adorned himself in feathers. Transformed, he waged battle.[3] For Tessi, painting is a body. But in that necessary being-self-and-other to engender a new species, painting might be a layering of skins or of makeup.

In 2010, Tessi began this pictorial cycle as a series of twenty works.[4] He started each canvas by following a set of instructions to apply makeup on humans. This series seemed to be a literal manifesto declaring twenty times that painting is always trans. As Fernanda Laguna says, “Painting is all the sensations and things (etc.) that make up the world, but staged, cross-dressed.”[5] In this series, though, a human body no longer acts as makeup’s topography. Makeup is now just a shapeless and expressive surface. Is painting human makeup set free? Or does makeup manage to free itself of the human in painting’s unbridled use of it? That is, Tessi’s painting can be understood as a body insofar as it puts on makeup, has a head, needs a prosthesis, gets wet when it rains, laughs, and dreams, insofar as things happen to it. But it is a body of a freed species: a trans-human painting. Tessi does not use the brain to transmute, dematerialized in cyberspace. What he uses, rather, is makeup—the body’s final layer of material representation—as the genesis of a new presence.

Mounted[6] Painting and Informalism’s Three Hunks

Juan del Prete is arguably the first bastard painter in Argentine art history, the first voice that disregarded origin, or with a multiple and dubious origin. Like Tessi, Del Prete would come and go in time. At varying paces, he expanded languages or reiterated them. He was an ardent advocate of different pictorial factions at the same time, which kept him at a remove from collectives and agreements, like the concrete movement. Something similar was at play in the mind of Xul Solar, where worldviews, symbols, and religions from the whole planet mingled. Perhaps together—one with the world of ideas and spirits, and the other with materials, styles, and ways of making—they founded something as paradoxical as the lineage of Argentine bastard painting, a school whimsical and arbitrary, intelligent, and localized by its special form of distance. A lyrical bastard, Tessi could be one of its last exponents.

In 1962, Del Prete called a group of his works “mounted painting.” He did not speak of trans or made-up painting, though he might have. He gave them that name because of the technique he used: mounting old paintings on new ones, mounting objects like an animal bone on a two-dimensional representation (just like when Tessi “mounts” ceramic heads or plastic bags on his works, or puts two paintings in one). In Juan Tessi, Juan Del Prete, and Xul Solar’s practices, we might discern a material and conceptual way to disassemble culture as univocal, a way to get through painting politically in search of a flexible—and, hence, creatively free—world that is much less brittle. Perhaps the spirit of Latin American painting where Tessi’s origin myth might lie has always had a trans agenda.

The fifties and sixties also found Alberto Greco, Rubén Santantonín, and Emilio Renart—exponents of one of the most powerful strains of innovative conceptual art in Buenos Aires—at a crossroads. Though they did not form a group at the time, they could be seen as a first prototype of what might be called a Rio de la Plata neo-baroque driven by pictorial excess and by those folksy browns and slick tango blacks that came straight from the hood, the docks, or the Abasto wholesale market.[7] Though it might sound clichéd, Santantonín’s “Things,” Renart’s “Biocosmos,” and Greco’s “Live Paintings” come out of the primitive chaos of informalism just as the new species created by Tessi comes out of the shapeless abstraction of painting-makeup.

Tessi’s solo exhibition Cameo at Malba (2016) was divided into two phases. In the first, security cameras showed paintings in an array of places on the museum’s grounds (its parking garage, its outdoor spaces, a hall outside an office, etc.) With that gesture, painting was further removed from the human. It didn’t even show up in an exhibition gallery to engage in a painter-viewer or painting-audience dialogue. Painting was, little by little, working its way up to direct communication with the world—something crucial for any new species. And Tessi, when he spotted them in the security camera alongside other objects like a broom, started to call his works “things.” “The Thing is the object happening. It happens thanks to that life that we give it when we conceive of it as thing,” wrote Santantonín in 1964 in Por qué nombro “COSAS” a estos objetos (Why Do I Call These Objects “THINGS”). Naturally, Santantonín was, by then, calling his viewers “peepers.” A few years earlier, in the late fifties, Greco was urinating on his paintings, treating them like a body that receives his body, a sort of homoerotic signaling of the pictorial being. Greco would leave his paintings outside so that things happened to them, for their makeup to run, for them to get dirty or take in the context—just like Tessi did in Cameo. Along with the works seen through security cameras, the first stage of Cameo also exhibited for the first time a series of beings with impossible-to-read titles (b147745d48049348e52dd0f72a24253a and bd862f4662d4bb277e591cc84e07c6ef, for instance). It was as if this species, even in the names and categories assigned it, resisted human reason and codes. With the use of indelible markers and ceramic heads, they expanded the limits of the canvas and recalled—if not in their imaginary, then in their hybrid strategy—Renart’s integralism and the heterogeneous biocosmos that emerged from the canvas by bringing in drawing, paintings, and sculpture in a corporality organic, excessive, and fragile in equal measure.

The question of origin is one of the creative amulets of Argentine culture. Tessi has the virtue of joining together two of local painting’s mighty origin myths. On the one hand, the bastard that knows no single root and turns to the multiple (this would be the case of Xul Solar and Del Prete, two painters as fundamental as they are unclassifiable). On the other, the chaos of informalism as genesis of a strain of pictorial thinking in the practices of Santantonín, Greco, and Del Prete. Tessi cynically replicates that thinking by beginning, in informal and trans fashion, with instructions to apply makeup. He shakes it up further, playing the conceptual painter, in the expansion of the limits of painting at stake in Cameo. Lyrical bastard and conceptual painter that surfaced from a trans big bang: two original myths that rattle dogma. That combination places Tessi, afloat, in his own dimension, somewhere where viewers are more peepers than interlocutors. A new species that prophesizes a symbiotic hereafter rather than an evolutionary fate.

New Species Painting

Tessi’s images have the ability to move from one place to another too fast, even when that means leaping between distant or even opposing forms and times. At the same time, they have been able, over the course of a decade, to make up a body of work that has a common origin myth and set of prophecies without establishing stiff discourses, narrative chains, or dogmas. A body of work that grows as if it were the body of a work with an array of different, but mutually-enhancing, extremities and organs: a new species with multiple ramifications, one more endosymbiotic than evolutive.

In 2018, Tessi’s exhibition Manglar (Mangrove) was held in Portugal. A mangrove is an amphibian habitat with twisted and tangled trees. It has sweet water, salt water, and land. A mangrove might be seen as the convergence of a number of different habitats: a certain pre-Columbian imaginary, the lyricism of a North American belle époque, Orientalist exoticism, the strategies of a strain of modern Argentine painting (its conceptual processes rooted in informalism). It is, in other words, an ecosystem that can hold numerous species. Perhaps one of the keys to the mangrove lies in the idea of endosymbiosis: a species is also the habitat of many others that engender the coming species. Prophecy is the mangrove’s symbiotic hereafter.

If painting is trans, it is a habitat where everything can relate to everything else—and that makes it an ever-free devotion that does not need to convey certain discourses. It is a locus politicus capable of bringing in worlds. Tessi’s is a strain of painting wanton when it comes to accumulating gestures, gods, and colors. In a sense, he is a painter who does not wage a historic battle, but rather produces beyond reproach because he knows full well that his gods are at his side—a confidence reserved only for a painter from a country or region that has been colonized. No First World painter could mix pre-Columbian art, her own histories, and Orientalist exoticism untroubled by a previous political morality. With love and hedonistic pleasure—not with a cannibalistic drive or from a territory that disputes history or symbolic capital—Tessi paints outward toward everything that strikes his fancy. He paints like a demiurge where from the mix springs a bountiful existence rather than a medium. Unlike humans, his species does not inhabit the age of dispute. It is grounded in trust—a Latin American trust?—in being engaged in generating a fertile terrain where shared gods will create new species.

—Text by Javier Villa, senior curator at Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires;

translation by Jane Brodie

—

Cf. Todorov, Tzvetan. La Conquista de América. La cuestión del otro. Siglo xxi editores, s.a. de c.v.. Mexico, 1987. p. 93. (English title: The Conquest of America)

Ibid., p. 171

Ibid., p. 101

The series was exhibited in its entirety for the first in the show Empujar un ismo, curated by this author at the Museo de Arte Modernos de Buenos Aires.

http://www.ramona.org.ar/node/62161

Montado (mounted) is a current Argentinean colloquial expression meaning “in drag.”

But the origin of Tessi’s art may well lie somewhere else. Picture a middle-class Catholic teenage girl in the suburbs in the nineteen-eighties surrounded by religious and costumbrist pictures, bronze ducks, exotics souvenirs from a trip somewhere, and dried flowers.

Comments

There are no coments available.