26.10.2019

By Marga Sequeira & Mariela Richmond

Ciudad de Guatemala, Quetzaltenango & Chichicastenango, Guatemala

October 1, 2019 – October 30, 2019

La Bienal en Resistencia [Biennial In Resistance] (BeR) is a proposal from Proyecto 44 and CARTI (Central de Artivismo e Innovación [Center for Artivism and Innovation]), led respectively by Maya Juracán (activist and curator) and Gustavo García Solares (audiovisual communicator and narrator). From the plurality of their projects, they created community curatorship narrative with Numa Dávila (Guatemalan anthropologist that works from her body and identity as a non-binary person), and Daniel Garza Usabiaga (Mexican historian and curator) for the conception of the action network and works that shape this event in different parts of the city of Guatemala, Quetzaltenango and Chichicastenango. Thus, during the month of October 2019 more than 40 artists from Latin America, especially Central America, were summoned to the Resistance: Colectivo Loco Sapiens (Colombia), Djassmin Morales / Elda Figueroa (Guatemala), De Mendoza Taca (Guatemala), Mariano González Chavajay (Guatemala), Rafael González Chavajay (Guatemala), Aiza Samayoa (Guatemala), Marilyn Boror (Guatemala), Colectivo Mórula (El Salvador), Antonio Bravo Avendaño (México), Colectivo Lemow (Guatemala), Anarkiperreo (Guatemala), Allan Raymundo (Guatemala), Luis González Muy (Guatemala), Fidel Caté Tuc-tuc (Guatemala), Miguel León (Guatemala), Esvin Alarcón Lam (Guatemala), René Leonel Vásquez Maldonado (Guatemala), Discordia Travesti (Guatemala), Alejandra Garavito Aguilar (Guatemala), UTOPIX (Venezuela), Inova Walker Morera (Costa Rica), Darex (Guatemala), Fredy Jeremías Araujo / Ernesto Cartagena (El Salvador), Misha Orlandini (Guatemala), Gala Berger (Argentina), Bryan Castro (Guatemala), Susana Sánchez Carballo (Guatemala), Mario Santizo (Guatemala), Wildredo Orellana (Guatemala), Lucía Rosales (Guatemala).

Aspiration or satire?

From Costa Rica, The Bienal en Resistencia was understood as a grand event: the open-call, the organization, the work selection, the venues, the internal and external communication, the desire to include views from all of Latin America, a month of activities, working from a community curatorship, prioritizing the public space and to place Central America as a space of enunciation. All of these ambitious elements present the biennial as a space with experience and, clearly, a large budget.

Simultaneously, the word resistance, placed together with the word biennial implicates a subtle noise. Subtle for it is easy to intuit that it makes reference to the inclusion of proposals and discourses that tend to be exempt from these hegemonic and legitimate spaces. Nevertheless, when arriving at Guatemala, this subtle noise transformed into a roar. It was perceived that this was not a “grand event”: the budget was narrow, the work force small and the venues were alternative spaces with diverse conditions and, even, turbulent.

The question arose as to whether it would be an aspirational exercise, which was intended to lead the practice towards the hegemonic discourse of the contemporary art system, despite not having the management and economic resources that, an event called “biennial ”, must have according to the parameters of said system. The answer came quickly when we became aware that the true Resistance was the context. The Resistance consisted of dreaming about the project, managing it and materializing it. Resistance is doing the same, because living and working in a territory like Guatemala, where life constantly faces vulnerability, violence, difference or repression, implies developing skills and strategies to do what cannot be done or has never been done. Resistance, in addition to exposing the current situation, implies certain ways of creating, constructing and thinking that do not necessarily respond to aesthetic or market logic, but instead appeal to concrete possibilities and that are the result, precisely, of a summon.

From the periphery, always

Imagine the opening cocktail, the formality and neatness of the walls, as necessary elements of a biennial, corresponds to a western and modern logic. These “artistic” logics that we assume as universal, work in some contexts, but if we enter the complex question of what defines art, we would have to take into account the particularities of each context in which the experience of art develops. In Guatemala, the discourse of this project needed other spaces and other logics to be expressed, because the most formal spaces are not interested in assuming the needs and intentions of a biennial that aims to “tell our stories from the resistance”, as the artistic editor, Rodrigo Villalobos, mentions.

The greatest achievements of the BeR have to do with the space where the body and the gaze are placed. The first intention of deinstitutionalizing art, or hacking it and making it available to anyone, became a powerful resource for linking bodies, spaces, themes, disciplines and contexts. From this premise, it is recognized that the venues must be accessible and proximate spaces for any public, that the public space in turn becomes the meeting space and that not only the visual arts are sufficient to build a curatorial discourse. It was necessary to recognize their own, know what resources they had available and to have clear expectations that they were not going to fulfill.

We observe enormous courage in positioning Central America as a discursive and generating space. At this time, where geopolitical issues place us as a leading space for great threats, asking ourselves about the Latin American reality from this thin strip, although full of aspirations, is also to state that there is still much to learn from Central America. Thanks to the BeR, we are reinterpreting the concept of biennial, learning to translate it, to appropriate it and bring it to everyday life.

Community Curatorship

This conscious exercise of taking control of our own forms of management also implied a transformation in the curatorial process. The BeR insisted on the possibility of telling “our other stories”, of placing non-hegemonic corporalities and native peoples in some art system, their own art system. For this to happen it was necessary to deconstruct the figure of the curator. Maya Juracán, inspired by the community feminism of Julieta Paredes [1], proposed the exercise of a community curatorship. If the curatorship has been that exercise of power, of unidirectionality on the decisions in the selection and exhibition process, the community curatorship worked as a dialogue between the views of those who were linked to the art system and those who were external agents of the same. This collaborative exercise allowed us to reflect the open-calls’ proposals from different points of view beyond the visual codes. Gustavo, for example, comments that he favored the figure of a less visible creator and gave more importance to the collective he represents and to having the possibility of placing himself in the public space. Naming curator someone who does not favor an aesthetic criterion when selecting a piece, was only possible through an exercise of mutual recognition and trust: based on common criteria to think about resistance, the other gazes, outside of the “artistic ”, also become important.

Daniel, Gustavo and Maya agree that a large part of the collective process was organic, that the different knowledge and places of action allowed for observing diverse elements in the proposals, that each person looked at specific things and that as a whole allowed for another curatorial exercise, another creative and collective process. If there is a deconstruction of an artistic language, if there is a questioning of the concept of biennial, or the selection of spaces/works/actions, they are precisely a consequence of this dialogic, participatory and affective work that involved questioning the exercise of authority within the curatorial criteria. As Maya concludes: “Art as a social exercise requires a larger figure than that of the curator”.

The Biennial with Cumbia [La bienal con cumbia]

This community logic extends to everything that operates on this platform. Networks and collaborations are the greatest resource available and it’s what allows the project to exist. Many people join with their own resources and collaborate from what they can contribute, mainly with their enthusiasm, commitment and solidarity, creations from a common goal. The involvement of artists from outside Guatemala City and the country itself, was an example of this collaboration, as well as the use and identity of the spaces used as venues.

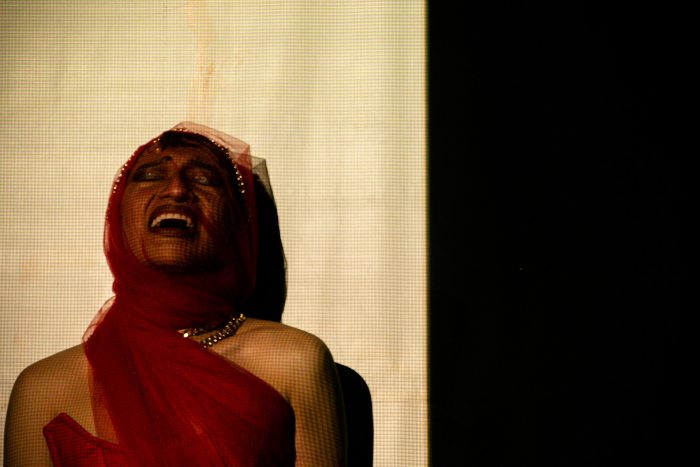

The main venue opened on October 1: Casa Celeste, a space that in its daily life hosts diverse events: corporate, community or personal. On the day of the inauguration, 8 huipiles woven by women from San Juan Sacatepéquez hung in the center of the room—a piece by Guatemalan artist Marilyn Boror—among them, dancers from the Colectivo de Improvisación de Movimiento de Guatemala [Guatemala Movement Improvisation Collective], wore shirts with faces of defenders of the earth, a dance in common, a movement of some with others, from the woven body to the absent body of those who nurture the spirit of resistance. After the opening ritual, the complete exhibition dances to the daily rhythm of Casa Celeste, between cumbias, salsa and merengue, but adding to its walls the documentation of artivist pieces of the collectives composed of Claudio Corrales, Jonathan Torres and Pablo Bonilla; Oscar Figueroa and Jeffry Ulate, both from Costa Rica; the Colectivo Mórula from El Salvador and the artist Aiza Samayoa, from Guatemala.

Espacio Cultural 4 de Noviembre and Casa Roja, in addition to being premises that function as a coffee house and small format restaurant, are safe spaces for people of the LGBTIQ community. In Casa Roja, the collective exhibition ARTISTAS EN CONTEXTO [Artists in context] was held, a show that we what consider necessary for this historical moment: “Nicaragua has experienced in the last two years one of the most complex political crises in our recent history. With a post-war generation, we, the children and grandchildren of the Revolution, meet with a reality of the dead, missing and a massive migration that has fragmented Nicaragua that once was presented as the safest country in the region”. This exhibition is shaped from diverse opinions, letting us see the stories that are embroidered beneath the surface, underground stories that contradict the official speeches of power.

In the Espacio Cultural 4 de Noviembre, a project that stands out is the curatorial project of the Museo del mundo [The Museum of the World] based on the women artisans of Livingston, the Garifuna area of Guatemala, an investigation that links artisan work with day-to-day work on the coast through what its creators call “educational collecting”. The need for discussing folk crafts in the BeR demonstrates the lack of archives and institutions that manage the research and visibility of these types of practices in this area of the country. The Museo del mundo has as a macro-objective, to generate didactic materials that map the artisanal work of various areas of the world.

The National Library of Guatemala is an old building in the center of the city. In the main lobby, a sequence of panels exhibits two shows that are intertwined in their installation: a rescue project of the Archivo Histórico de la Policía Nacional (AHPN) [The Historical Archive of the National Police], which the Guatemalan art-educator Misha Orlandini narrates, and a project to invent the memory, created by the Guatemalan collective DAREX (whose name means, duet of experimental art). Orlandini, uses information from the ANP and her family archive to reconstruct a part of her grandfather’s life, and consequently an era of Guatemala. She uses both files for with one completes the other’s gaps. Her grandfather was persecuted, monitored and marked by the police between 1955 and 1983 in the context of the armed conflict. Her uncle was persecuted, kidnapped, tortured and killed. The opening of the AHPN showed how common these practices were and the structure that operated them. The need to know and understand what had happened led many people to consult these files and find information about their families.

For its part, Anti-historia [Anti-history] is the first exercise of the DAREX collective, an exploration that aims to show a polarized contemporaneity with Cold War arguments, simply pursuing an ideological disqualification. According to the duo: “It is not a yearning for a country, but a proposition of questions that tries to appeal to empathy and to question the ideological positioning of individuals from the place where the historical seizures left them frozen”.

In Guatemala, under the new government, archives of this type are at risk; information is evidence, say the authorities. Therefrom, the importance of activating the archives and thinking from memory as an engine to express narratives that have been made invisible, to give rise to other ways of looking at these documentary circuits and to transform them into intersection nodes that demonstrate the past that summons us.

Espacio C, in Chichicastenango, is a small room attached to a restaurant, which takes advantage of the customers to link and bring together the exhibitions they host. For this space, within the framework of the BeR, Diego Ventura created a curatorial discourse with pieces from his family’s collection composed mostly of Mayan artists from the area, in contrast with newspapers linked to the rescue of their native tongue and the Resistance from that territory.

Knowing these spaces and these exercises, showed us that radical self-criticism is not necessary, but that what is necessary is to create together, in Resistance, in the unknown or unthinkable, in the streets and inhabited spaces, with and from the body, with those who want and can collaborate, from dialogue and horizontality, with an economy of affections, with ease, leaving the centralized territory, outside the white cube, working with the invisible, with the irregular, with what from intuition, desire and need can be built.

We decided to focus this report of the biennial on its venues, since our stay in Guatemala was short and did not cover the entire month of actions proposed by the biennial; we were unable to recognize and document in its totality all the ephemeral spaces that were built in the different performatic actions and activations within the framework of this vital Resistance. In two more years, hopefully making use of the powers of the art system, we’ll be attentive and open to what the second edition of this hybrid and pulsating exhibition will bring.

In the link of the biennial, more information about the artists, spaces and actions involved.

The community feminism “inscribes in the ancestral struggles of women in front of the patriarchy, it is born in our contexts, in our bodies, in our circumstances, in the dreams that we want to build […] It has to do with an autonomy concept […] It has an epistemic matrix of its own, that arises from our history, of large memory, of the recovery of the female ancestors’ fights. It distances from the modern-libertary epistemic matrix. […] It thinks from the common identity, the collective body, the side to side”. (Julieta Paredes, Feminismo comunitario, Asamblea Feminista Comunitaria, UNIFEM, Bolivia, 2010: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NrivDMl1qDU)

Comments

There are no coments available.