28.10.2022

On the show El águila y el dragón by Marek Wolfryd at General Expenses

It was by mere accident that I came upon El águila y el dragón [The Eagle and the Dragon] almost at its completion. A grayish green tone was missing on one of the walls. When I entered through the small door, I traveled to another time. The white cube was gone, I was transported to an ancient setting of relics and precious objects. First, I was filled with a strange warmth, product of the yellow and red colors of the walls, then I saw a treasure. Our attraction to treasure is inevitable, and there it was in a Spanish chest on a tea table; dozens of ancient and precious coins. Being the work of Wolfryd, there must be a trick. You never get what you see when you experience his art. The real power of the world is found in the way we are seduced by commodities. Upon entering, a cultural history of power and desire was evidenced with a gesture.

Then I saw The Tiger Hunt (1615) by Peter Paul Rubens but with a sphere in the center that I mistook for a mirror. From the entrance it seemed that the sphere reflected its environment and that of the painting. Yet another trick, you saw The Tiger Hunt but it wasn’t The Tiger Hunt, it was Gazing Ball (Rubens Tiger Hunt) by Jeff Koons. It is, to say the least, strange to show the same work three times, the artwork is unique!

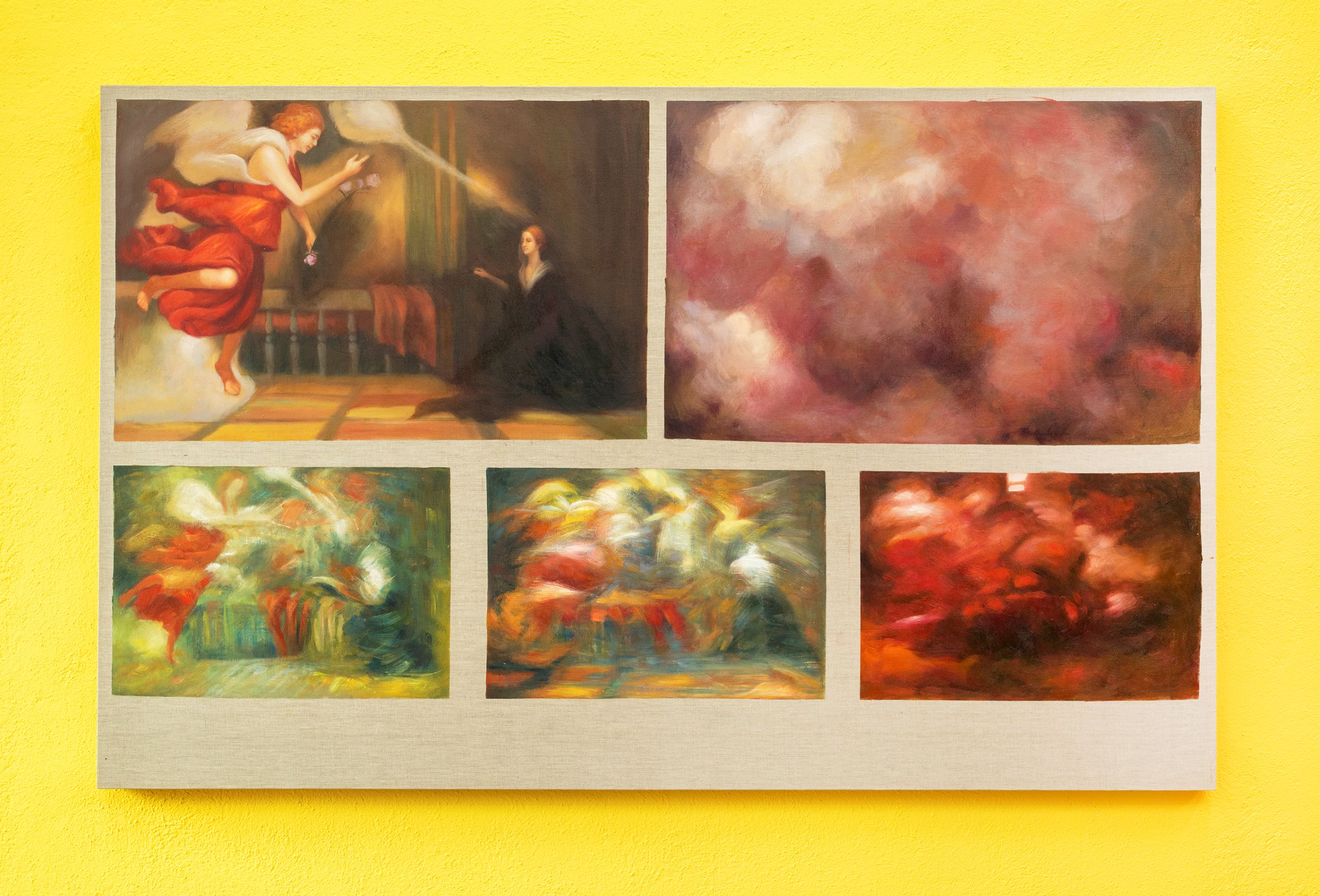

Painting of a Distant View or Perspective Picture of the West – Jeff Koons, Gazing Ball (Rubens Tiger Hunt), 2015 by Marek Wolfryd is the staging of the contemporization and blurring of the status of authority and originality of painting through its fictitious transnational character. Koons introduces the sphere to Rubens’ painting, Wolfryd adds two more identical paintings to show how the contemporary is also the productive possibilities in global exchanges. Rubens’s painting alludes to orientalism in representation and Marek’s makes it explicit in the production chain. It was made in collaboration, as he calls it, with Zheng Lihong and Shenzhen Melga Art Co. Ltd. A company of Chinese painters who practice copying as art. It is about seeing the pictorial process as a series of translations at play with symbols, territories and commercial exchanges.

El Águila y el Dragón is the transformation of a gallery into a temporary museum of the material origins of globalization. Due to the type of objects that can be found there, it was about thinking of art as a sensible fact of history.

The show stresses and tries to dilute—through commercial arrangements and mediations—the categories of artistic modernity. But the name itself weighs too much. Each work has its history inserted in the aesthetic, political or economic canon. It cannot escape, due its very configuration as well-made objects and works, from authority and art. It is true that Wolfryd’s place is different from that of the easel painter, but he cannot renounce the name no matter how much he delegates the work and symbols. I think about the limits of conceptual games: how far can an image be erased so that it continues to function in the market? How far can one delegate the work, but still claim it as one’s own? How to maintain a practice when you want to eliminate it? Perhaps this model of production builds a larger figure of authorship. Not only because it dominates more media, but also because there is intellectual, technical and monetary value at stake. It is not the artist’s hand that creates and claims his work, but a whole semiotic apparatus that exceeds them.

Of the seven pieces, none is just that. Each material has an origin, each item a story, each image its tale. All of them question their production and authorship, in them appear authors such as Gerhard Richter, Damien Hirst, Andy Warhol and Eduardo Sarabia—each famous for questioning the art world, pop and capitalism—as well as Titian or Rubens. But it is not only an exhibition of art about art, here materials and forms speak for themselves; marble, jade, talavera, porcelain, the box and the vase have agency and are narrating commercial processes.

Un amuleto para la suerte y la abundancia [An amulet for luck and abundance]—a traditional Chinese table, a Spanish chest and eighty coins made of brass of a Real de a ocho minted in 1756—its a success for it covers major key elements of the artist’s general practice. These coins symbolize globalization; they began to circulate in 1497 for the Crown of Castile. They were minted in Casa Moneda (Mexico/Bolivia/Peru) with silver from Bolivia, Potosi, Zacatecas and Guerrero to acquire merchandise and raw materials from the Orient via the Manila Galleon (Acapulco/China). By the 17th century it was already in official use in China and the South Pacific. What is interesting is that these coins were marked by Chinese bankers and merchants as a guarantee of their value. I especially highlight this work in the exhibition for its value in terms of historical unity and its conceptual gesture against the unity of the work of art from the market.

One of the tools for organizing the social body, once the figure of the monarch fell around 1808, was the idea of power and nation that was disseminated in non-sacred forms such as flags and coins. The empty figure of the sovereign was filled with allegories and national symbols that conjugate territory and history through the use of coins. To have a sealed coin is to be part of a complex symbolic construction. Wolfryd mints coins and thereby questions the value and representation of evanescent entities such as authorship and the artist.

The game of coins is to date the inapprehensible figure of the creator as producer and trader by imposing his stamps—of the artist and gallery. It evidences the art world system as a global business while highlighting the impossibility of being the author of a symbolic and commercial tool. In its scarce historical value as art and its staging of history, the sculpture—which will disappear as the coins are sold—becomes an object that narrates how the market and history put an end to authority and fixed unity. The 80 buyers build for the future space invented within the exhibition for the future.

In the commercial transits of the works, in their anachronistic referentiality and remediations, the movements of expanding capitalism are revealed. Only wealth projects the utopian horizon of global social interconnectedness, the market being the place where something beyond the territory happens: the experience of the connected world. Marek uses the history of art, yes, but he does so from the most vulgar practices of art, which at the same time gives it its international value beyond referentiality: its objectuality as merchandise.

The way in which art ceases to be a double standard of bourgeois cultured morality is when its autonomous character enters into conflict and negotiation with its commercial essence. Only by recognizing the complicity of aesthetics with money, can the artistic phenomenon with its geographical and social implications be understood. The in-situ museum El Águila y el Dragón harbors tensions in images connected by power, the expansion of capitalism, the use of raw materials that assemble the idea of the world in motion. It could be that in addition to stories, this series of objects, whether artistic or commodities, are ruins of the bourgeois project that hatch over time.

Comments

There are no coments available.