03.06.2023

Paige Haran writes about Third World Mixtapes: The Infrastructure of Feeling, Shellyne Rodriguez’ solo show at P•P•O•W

In her first solo show with the New York P•P•O•W Gallery, Shellyne Rodriguez homes in on a vital part of her expansive practice: elevating the lives of working people into visibility and reverence. Third World Mixtapes: The Infrastructure of Feeling goes beyond an exhibition, becoming a framework for the expression of life and freedom, complete with teach-ins, community talks, a playlist, and bibliography.

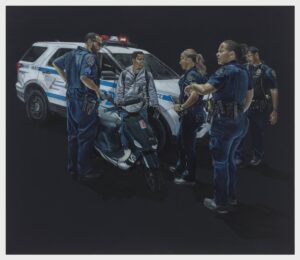

The 22 luminously detailed drawings, based on photographs of the artist’s surroundings in the South Bronx, evoke a baroque quality—where everyday objects, slogans, neighbors, and comrades take on new splendor. Her coined phrases, such as “Broke Baroque” or “Baroque from Below,” are derived from hip-hop vernacular and offer a window into the artist’s shapeshifting sensibilities.

Broke baroque, as Rodriguez expounds in her 2017 interview with the Jewish Museum, means her work is “emotive, it’s referencing those timeless existential feelings about life and suffering.” The remix of baroque—the gilded, expressive era in Europe of the 17th and 18th centuries—imbues further meaning. In the same way that hip hop has long served the Black community in America as a form of resistance, baroque from below not only emotes but reclaims the style as an anti-imperial life force: “When it comes to people of the Bronx [my work] becomes a conversation about indignant survival and ingenuity.”

As an archival act, Rodriguez’s drawings in P•P•O•W pay homage to elders and activists in the borough such as abolitionist and geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Savage Skulls former “first lady” Lorine Padilla, and gay rights and AIDS historian Sarah Schulman. In the portraits, their clothes are alive and almost mischievous. Gilmore’s zealously multi-toned orange pants are ready to jump off the page. The two-dimensional works draw you in to understand figures in the community in a three-dimensional way.

The Bronx is for Rodriguez an example of what Gilmore refers to as “infrastructure of feeling.” In Gilmore’s teachings and Rodriguez’s exhibition title, the “infrastructure of feeling” signifies an abolition geography; despite the “carceral geography” across America, working class people can coalesce in the persistent act of freedom-making and place-making. The borough and Rodriguez’s work alike are pollinated with migrants from the global south—Bangladeshi, Cameroonian, Chinese, Dominican, Haitian, Mexican, Nigerian, Puerto Rican, and more—and descendents of the Great Migration within the United States. Together, they have created an ornate and defiant topography alongside New York City, “the periphery of empire.”

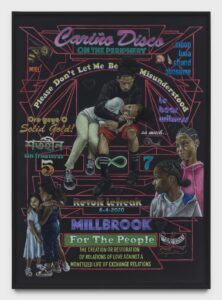

Honoring daily life and working people, Third World Mixtapes exists in the lineage of the Ashcan School and portrait artists such as Alice Neel, but beyond those Rodriguez’s pervasive use of alliteration, puns, and anagrams become a form of artistic guerrilla warfare. Her three large-scale Mixtapes landscapes expand on the Buddy Esquire-styled hip-hop party flyers of the 1980s and convey both invitation and social mobility. The headlines “Siwanoy Snakapins Style” and “Rananchqua Rockers” bring the indigenous people of the Bronx to the foreground. Like the diagonal Art Deco trajectories in Esquire’s flyers, Rodriguez illustrates her community’s defiant wayfinding that continues to break through.

Other moments in the Mixtapes flyers cast a spell. In BX Third World Liberation Mixtape no. 2 (Esquire Strikes Empire), the text “Sink Vernon C. Bain” is overturned and situated next to a spoon, a tool once used in a jailbreak and now a symbol of Palestinian resistance. These moments are hidden messages rather than sweeping gestures. The small utensil alongside the rallying cry to submerge Vernon C. Bain, an 800-bed floating jail barge in New York City, could easily be missed in the close-knit world of Rodriguez’s landscapes. Whether the viewer catches wind of this pairing or the sacred geometry of her spiraled architecture, shells, numbers and snails, the magic and seeds of uprising radiate. In small, steady, everyday ways Rodriguez is weaving together liberation movements and fermenting her worldview.

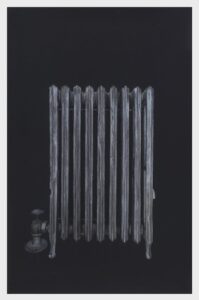

In her drawing The Common Denominator, the artist commemorates the shared reality of a radiator. For all the tenants in Rodriguez’s building, the radiator is a collective axis on which their lives revolve: If the boiler breaks, everyone feels it. Because of this, the radiator becomes the common denominator, galvanizing people in a shared struggle. The common denominator extends even to the artist’s tools: color pencil on black paper. The materials are accessible, unassuming, yet as Rodriguez demonstrates, they hold power to metamorphose into insurgency.

Rodriquez has molded everything in this exhibition, even the gallery space, into a political toolkit. By her own admission, the show is didactic. Linger longer than a snapshot view and viewers will find the tags of local graffiti artists on distant rooftops, a keffiyeh draped across a sofa, the historic petition “We Charge Genocide” tucked in a bookshelf. These details nod to a well-informed life force in the borough that can’t be held down.

Scramble the letters of baroque and you arrive at quebrao, or quebrado, meaning “broken” in Spanish. Not always, but sometimes the art cycle manages to spin slower than the news cycle—in a way that breaks what Rodriguez refers to as capitalism’s acceleration of time. In Third World Mixtapes, full of hand-drawn intimacy and double entendres, the work embodies the artist’s deep devotion to community. A taproot that taps in.

Collaborator’s Note: This piece was written during the closing of Shellyne Rodriguez’s solo exhibition at the end of April. As of May 24, Rodriguez, a college professor, was fired from Hunter College after an incident with an anti-abortion student group on campus and later a right-wing journalist from the publication the New York Post, who showed up at her private residence.

Editor’s Note: In Terremoto we recognize how important is the articulation and political mobilization against fascism and all forms of violence that arise from it. To remain alert and sensitive to what surrounds us demands from us concrete collective actions. Recognizing and naming the acts of fascism that convey racism is one of them. We want to express all our support and solidarity towards the teacher and artist Shellyne Rodriguez. Every offense is collective.

23.03.2024

Opinion Cartografía sentimental de la brutalización en curso Argentina, Latinoamérica

Duen Sacchi

22.03.2024

Marginalia

(Español) La Revuelta

08.03.2024

Opinion

María Galindo

Comments

There are no coments available.