07.07.2022

Amid branches, foliage and fauna, art historian Amalia Cross walks through the halls of an exhibition that illuminates memory with firefly light, and expands the limits of the institutional through a jungle museography.

El arte es en algún momento un animal vivo [At Some Point, Art Becomes a Living Animal][1]

En la selva hay mucho por hacer [In the jungle there is much to do] is the name of the exhibition curated by María Berríos in collaboration with the team of the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (MSSA), as part of the celebration of its fiftieth anniversary. In this exhibition, more than one hundred works have been selected to rethink the principles that were the pillars of the museum at the time of its creation, in 1972, in relation to the political histories that gave life to this project and in opposition to the idea of the museum as an institution of confinement or dispossession.

The title of the exhibition refers to the book album that Mauricio Gatti, a young Uruguayan anarchist, made in 1971 at the Centro de Instrucción de la Marina in Montevideo, where he was imprisoned by order of the repressive government of President Jorge Pacheco Areco. In the book, made up of letters and drawings, Gatti tells his daughter about the causes of political imprisonment and the importance of interspecies solidarity through a fable starring a group of animals that, after being captured by hunters and taken to a zoo in the city, plot their liberation and manage to return to the jungle, where they live in freedom, taking care of themselves and their environment.

From the fable, and from the exhibition, at least two lessons or morals of the story emerge. On the one hand, the analogy between museum and zoo enunciated by Palestinian artist Noor Abuarafeh in the video Am I the Ageless Object at the Museum? (2018): here the voiceover reflects on both institutions, pointing out that they have much in common than just the animals, locked up or stuffed, referring to the political memory and colonial gaze that sustains them. On the other hand, a confirmation of the fragility of freedom in the face of the imminent danger of being imprisoned, as were several of the artist–as political prisoners—who make up this exhibition. These experiences can be seen in the engravings that Guillermo Núñez made after being captured and tortured by agents of the dictatorship in Chile (Carpeta de libertad condicional, 1975-1980) or in the drawings made by the Kurdish artist Zehra Doğan on the back of the letters she received during her stay in prison in Turkey (Los dibujos ocultos, 2018-2020). Because, in Gatti’s words, any day “… without being seen, a hunter arrives in the jungle, who does not understand anything about the jungle, nor does he care that the animals live better”.

Victoria Santa Cruz. Me gritaron negra, 1978. Still of Victoria. Black and Woman, de Torgeir Wethal (dir.), Perú/Dinamarca, 21”.3’58”. Photo Benjamín Matte, Image courtesy of the MSSA

María Teresa Toral. Juegos (8) Homenaje a Trinka (Teatro de marionetas), 1970. Agua fuerte, agua tinta, rulett impreso en relieve color 75,6 x 43 cm. Photo Benjamín Matte, Image courtesy of the MSSA

Following Gatti’s story, among jungles, museums and prisons, one of those hunters could have been Carl Akeley, taxidermist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Donna Haraway wrote about him and his excursions through Africa, focusing on his dioramas to expose how in his museography and visual technology the ideology of white supremacy and capitalism that sustains the invention of a form of exhibition is constructed.[2] This science, Haraway will say, “combined with a transcendent ethic of hunting” and plunder are the basis of modern museums, whether of history, art or natural history. In their name, hunters arm themselves with rifles ready to kill elephants to hang them on the walls of their homes, deposit them in museum showcases or lock them up in a zoo. Faced with such a panorama, the exhibition proposes to see the museum in a different way. A museum—like the one in the story written by María José Ferrada for the catalog—that protects us from hunters, that enlightens and shelters us. One that is built among all of us, in solidarity and transgenerationally, with “drawings made with yellow pencils, fireflies’ light, jars of honey”.[3]

The exhibition spreads throughout the museum’s rooms as when trees are no longer pruned, weeds are no longer removed and the walls end up covered by ivy. One is lost in the exhibition halls, at the same time that the museum loses its traditional sense. Upon entering, the expectation of a conventional exhibition is favorably diluted, because there is no single narrative that determines a “correct” tour or an “ideal” viewer. Instead, there are drawers and chairs, large and small, where to sit and read books, look at the works, take time to change direction or thought. Diversity abounds: there are engravings, drawings, paintings, videos, sculptures and plants, many paper plants. And in between, at a lower altitude, animals that look at us: the rooster of Joan Miró, the heron of Ernesto Cardenal, the gorillas, giraffes and snakes of José Gamarra, the horse of Santos Chávez, the crocodiles of Leonora Carrington, the penguins of Bélgica Castro or the elephant of Inés Agüero.

But the jungle is also a way of thinking and a metaphor to refer to the museum outside the museum. And thus strategically recovering the premise that would be the birthmark of the museum. The origin of the MSSA—and its survival in exile during the dictatorship—is closely linked to the campaigns of Salvador Allende and the Unidad Popular government, in the development of a revolutionary and therefore mobile idea of culture: a will to mobilize art in pursuit of a political cause.[4] The serigraphs of El tren popular de la cultura of 1971 are part of this line, among other initiatives that refer, in turn, to pedagogical missions of the Segunda República Española and the Soviet agitprop trucks. In all these cases the artists were volunteers who took art and culture on foot, by donkey, car or train, to the rural areas deploying cinemas, libraries, exhibitions or stages. These experiences and actions are updated and become contemporary in the exhibition: in the drawings of Oscar Morales with his different fantastic machines to get out of confinement; in the audiovisual pieces by Bartolina Xixa and Naomi Rincón Gallardo who, in the format of You Tube video clips, dance and fight against environmental damage; and in the children’s books that make up—within the exhibition and as a fundamental part of it—an itinerant library of other popular libraries in the country.

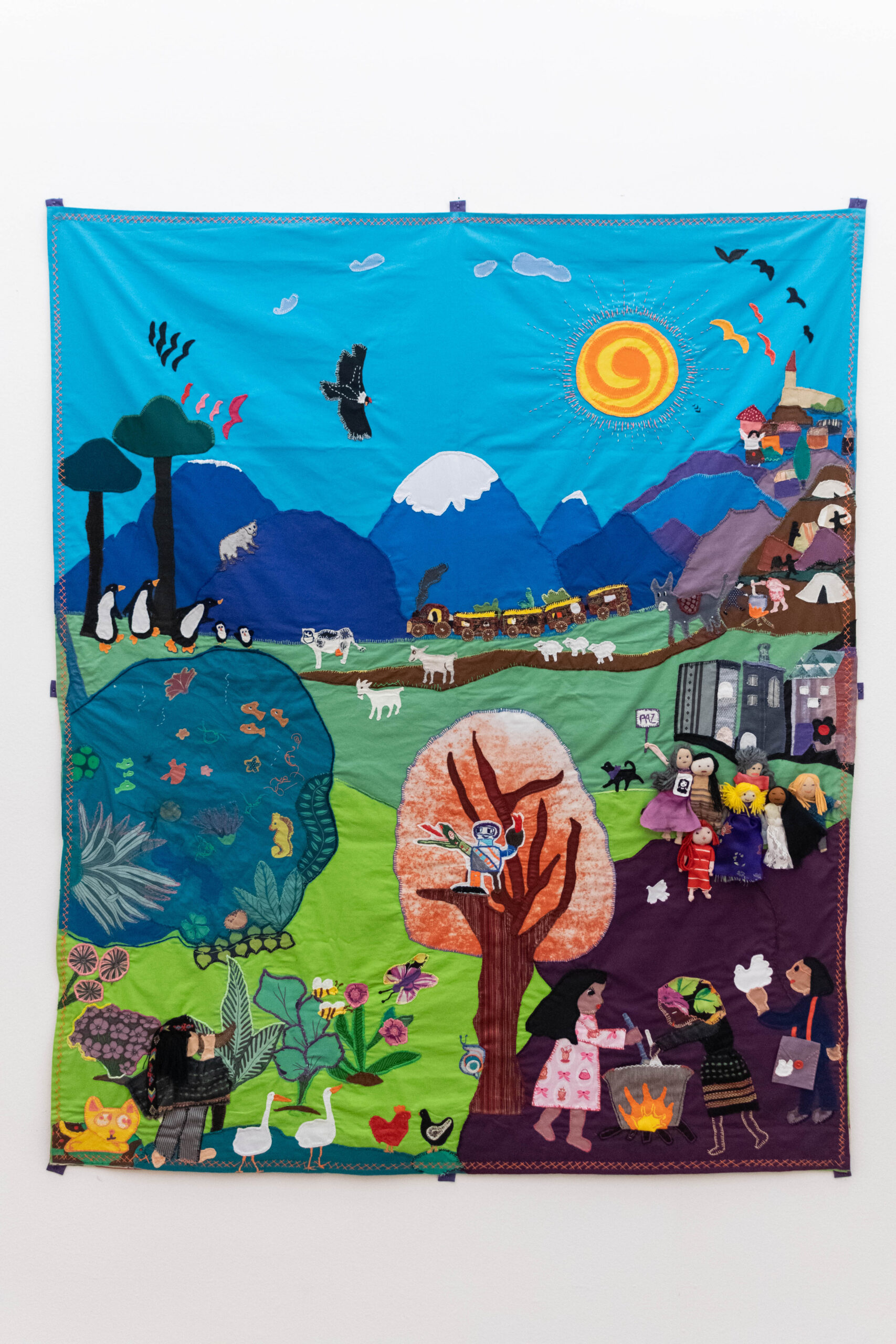

View of work on exhibition En la selva hay mucho por hacer [In the jungle there is much to do]. Image courtesy of the author

All this makes us think of the works and books in the exhibition as traps for the hunters, that is, as counter-hegemonic weapons of resistance. Traps that are incorporated into a jungle museography that relates to the radical museology that, in the words of Claire Bishop, is typical of “a more experimental model of museum, less architecturally determined and more politically engaged with our historical moment”.[5] Unlike a diorama whose glass “prohibits the entry of the body” or the white cube that eliminates all traces of context, the exhibition In the jungle there is much to do breaks the glass and makes the cube a colorful habitat for the works. It is, in the words of its curator, “an anti-museum where volcanoes and pumas roar, and remind us that the jungle is life,” for everyone but hunters.

A final lesson: Akeley died in Central Africa while hunting gorillas in the jungle. His body was buried there and, years later, looted by grave robbers.

Maxi Mamaní, Ramita Seca. La colonialidad permanente. Photo Benjamín Matte, Image courtesy of the MSSA

Exposición En la selva hay mucho por hacer — 50 años MSSA

por María Berríos

LA SELVA

La selva es muy grandota y para todos hay lugar… para que todos tengan niditos

todos tienen que ayudar

—Mauricio Gatti, En la selva hay mucho por hacer, 1971

El cuidado de las selvas, los bosques y las aguas es una práctica colectiva, milenaria e intergeneracional. Para muchos la naturaleza y los animales no son entidades externas: son familia, hermanos y hermanas, abuelos y abuelas y son ellos, en su generosa abundancia y sabiduría, quienes cuidan del buen vivir de todos. En la selva hay mucho por hacer, el libro de Mauricio Gatti, parte con el reconocimiento de la riqueza y solidaridad interespecie de la selva. Pero no todo está bien: hay quienes quieren extraer, explotar, encerrar, para el beneficio de unos pocos. Múltiples mundos se han perdido en ese impulso por poseer, por encarcelar, por tener siempre más, por convertirse en dueños de otros. Los grandes museos del mundo se construyeron sobre esas muertes, exhibiendo los pedazos de esas vidas rotas como trofeos de su distinción, de su cultura. ¿Cómo recordar todo aquello a lo que no le fue permitido existir? ¿Cómo contar las historias de esas otras experiencias, cuya mera existencia es lucha? Hay quienes no olvidan y resisten: los sonidos antiguos de los pájaros, los animales, los ríos y las piedras violentamente extraídas que cantan, truenan, sobre las ciudades y las montañas. Sus bibliotecas son el territorio. Esta es una biblioteca popular de ese pluriverso, un antimuseo donde los volcanes y los pumas rugen, y nos recuerdan que la selva es vida.

LOS ANIMALES Y LOS SUEÑOS

Los animales quieren levantar una selva donde nadie lo que necesite le vaya a faltar… Y enseñar a sus hijitos que en la selva para todos hay lugar

Animales del paraíso, mecánicos fantásticos, que llevan los paisajes en los ojos. Cocodrilos escondidos debajo del plumón, animales monstruos y pájaros del Edén. Elefantes y caballos que regañan al niño enfermo Ange- lito por levantarse de la cama. Animales que juegan en los sueños electrónicos. La leche del sueño que permite al poeta fugarse de la camilla y del hospital.

GUARDIANAS DE LA SELVA

…a la selva la quieren mucho, a sus ríos, a sus árboles, a su tierra y a sus frutos

En Abya Yala los pueblos siempre supieron que su territorio, su selva, era indivisible de la vida misma. Así lo celebran mujeres y niñas Guna armadas con agujas muy finitas, utilizadas para confeccionar los trajes para su vida cotidiana como guerreras de su territorio. Así lo hacen mujeres, que en un duelo rebelde y colectivo, tejen juntas en honor a una lamgen muerta por defender su territorio. Es un saber que se vincula con trabajar la tierra, conocerla de cerca permite defenderse y sobrevivir, escabulléndose entre los campos de arroz y los bosques vietnamitas bajo el acecho de soldados invasores. Para algunos solo existir significa lucha y rebelión. Así lo cuenta Don Durito de la selva Lacandona donde todos, con sus estrategias de caracol, construyen “un mundo donde quepan muchos mundos”.

EL FUEGUITO

En la selva los animales se dieron cuenta que hay cosas por arreglar, se juntan alrededor de un fueguito y se ponen a conversar

¿Puede un museo ser un arma? Artistas, poetas y cineastas viajan por el territorio, con la certeza de que quienes viven en las montañas y en el campo deben también experimentar, ver lo que se ve en los gran- des salones de los museos y en los cines de la capital. Van en tren, en automóvil, en burro. Un museo del pueblo no tiene ni adentro ni afuera, no se atrinchera en los muros blancos, sino que sale a la calle, a las provincias, a la cordillera y al campo. Ahí desenrollan sus telas e instalan sus proyectores portátiles, con la certeza de que la cultura y el arte tienen poder revolucionario porque son del mundo. El arte es solidario, no se puede encerrar ni poseer. Eso es político.

LOS CAZADORES

Un día sin que lo vean llega a la selva un cazador, que de la selva no entiende nada, ni le importa que los animales vivan mejor

Los cazadores del mundo lanzan sus bombas, desatan sus Guernicas, traen devastación, guerra y muerte, y lo llaman progreso, dicen que es el futuro. Sus armas más peligrosas son el miedo y su propagación. Pero son ellos los que temen. Le tienen miedo incluso a los papeles y a las imprentas, lanzan libros a la hoguera, le temen a sus palabras, a sus colores, a sus ideas que queman por considerarlas peligrosas, subversivas, disidentes. Los cazadores policías y militares quieren todo en blanco y negro, solo ven ganancia o pérdida. Siguen los mandados de sus señores, que son los únicos que realmente lucran. Pero ni los cazadores ni sus señores entienden que la riqueza de la selva es otra cosa. No comprenden que en la selva no hay ganancia, solo vida.

PRISIÓN POLÍTICA

El zoológico no es un sitio donde pueda vivir bien un animal, porque los barrotes lo separan de su trabajo y de su hogar

Los regímenes carcelarios del mundo entero continúan en su afán por encerrar y separar a los que están en desacuerdo con los señores que mandan y sus cazadores. Encierran a los más pobres, a los de tez más oscura, a padres, madres, niños y niñas por el solo hecho de saltarse un muro o cruzar una frontera. Hoy se continúa persiguiendo y encerrando a los defensores de las selvas del mundo. Sin embargo, las cárceles que son deshumanización y tortura también siembran indignación, solidaridad y lucha. ¡Libertad a todos los presos políticos!

DESTIERRO

En el zoológico muy pensativos a veces los animales están, se acuerdan de todas las cosas que en la selva hay que cambiar. Ellos quisieran también estar ahí para ayudar, y enseñar que en la selva para todos hay lugar

El destierro es una cárcel sin paredes. El exilio y la migración forzada implican cargar con una falta de pertenencia permanente, hacia delante, pero también hacia atrás. El país, el territorio, el hogar que se deja desaparece y se convierte en un lugar al que ya no se puede volver, incluso cuando se logra regresar. Océanos, desiertos y montañas se vuelven fronteras que separan, y también fosas comunes de los caídos. Esas vidas robadas no se pueden reparar. Pero hay quienes humanizan y suturan esas experiencias, luchadoras que crean nuevas antifamilias, sobrevivientes que se sostienen unas a otras, que comparten sus historias. Historias que se repiten, que suceden y vuelven a suceder, y por eso se tienen que escuchar.

CINES REBELDES

…con todo lo que tienen que hacer, con los hijitos que tienen que cuidar, ahora nadie de la selva los podrá sacar

Desde el perímetro, por los bordes, se levanta un pluriverso de voces rebeldes. Defensoras y guardianas del territorio que acechan a los cazadores que no respetan la selva y toman siempre más de lo que necesitan. Ellas ven claramente la relación entre los zoológicos, las cárceles y las bóvedas oscuras. Juntas revientan candados y desmantelan rejas. Ese es su cine-liberación. Y aunque no las vean o no las quieran ver, andan repartidas por los montes, los bosques, los valles, los ríos, las costas y las calles. Son muchas, serán más y vencerán. Cantando. Bailando.

Fragment from the poem “Arte contemporáneo” by Elvira Hernández (Los trabajos y los días. Santiago: Lumen, 2017, 273).

“The owners of the great machines of monopoly capitalism (…) needed a science that would ‘establish’ the jungle peace (…) combined with a transcendent ethics of hunting”. Donna Haraway, “Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden” in Social Text No. 11

(New York City: Duke. University Press, 1984-1985), 20–64.

María José Ferrada, “Vamos a hacer un sol”. En la selva hay mucho por hacer. Santiago: MSSA, 2022.

On the history of the MSSA, see: María Berríos, “‘Struggle as Culture’: The Museum of Solidarity, 1971-1973”, Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry, (London), Issue 44, Fall–Winter 2017, 130-141.

Claire Bishop, Museología radical. Buenos Aires: Libretto, 2018, 8.

Comments

There are no coments available.