22.02.2020

Index Art Book Fair @kurimanzutto, Mexico City

January 23, 2020 – January 26, 2020

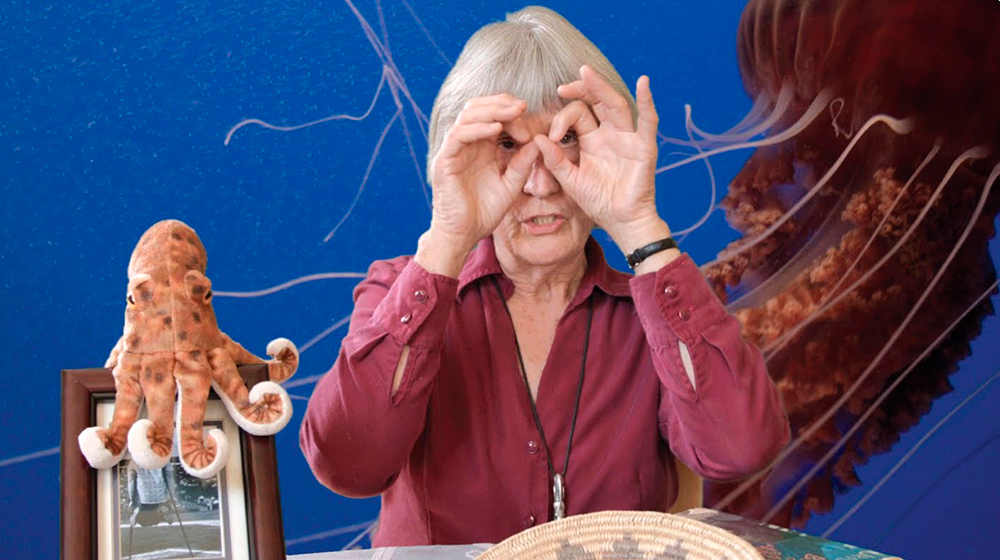

Donna Haraway, a feminist biologist and anthropologist, works around ideas that follow a feminist, anti-specist and cyborg genealogy that abbreviate speculative fiction and science fiction as narrative powers to raise a Chthulucene future, that is, a multi-conscience and ethic-species anchored in the collective responsibility of inhabiting the effects of current capitalism in bold and creative ways.

Within the framework of Index Art Book Fair, in cooperation with kurimanzutto, Donna Haraway visited Mexico City in a context of gradual socio-political deterioration, which has recently manifested itself in violence in multiple aspects, with particular pain in Femicide violence. During her visit, Andrea Ancira, researcher and curator, talked with her about the relationship between academics and the university as part of social movements, reproductive justice, and identity politics within the framework of a politically and socially situated thought.

Andrea Ancira: I recently watched Fabrizio Terranova’s Donna Haraway: Story Telling for Earthly Survival. I found particularly interesting when you pinpoint a series of important conditions for organizing your life, your academic work and your writing in the house you share. From the balance between physical and intellectual work, considering that worlds create stories and that the stories we produce every day allow us to speak and imagine from our own place and position, how do you build knowledge both outside and within the academy? Outside and within the movements and political networks from which you think and act? How do physical and intellectual work, care and companionship fit into your writing? I’m thinking, for example, in the tensions between socially engaged research and academia in the context of prevailing privatization of knowledge and epistemicide that comes with it.

Donna Haraway: In the early 1980s, already working in the university, a group of us who had been a commune bought land together and repaired an old house. We sought to trigger a collective imagination together through working the land, connecting to different movements in that way. That really did not succeed, not the way we imagined it. It was an important period of social movement in which those of us with academic jobs began to understand the degree of our own privilege. It was important personally, but I don’t propose it as a model to follow. However, I do have strong feelings towards connection work within the university; making knowledge and teaching with each other at the university. The public university is a beautiful and unusual institution, the care of the university apparatus involves working against the ranking of university positions and the privatization of public universities. That is being academic.

From my own experience and ideology, it’s very important to connect with people working in different areas. That’s why I’m part of the Center for Creative Ecologies, of the Science and Justice Research Center, and work with artists and activists in the university as well as ethnographers, literary people, among others. What I mean is that the university must be in connection with the struggles happening in the city that hosts it. In the case of California, which is where I live: affordable housing, homelessness, and water justice in the center of the state. All of the above in relation to immigration issues.

Despite being retired, I support and I am part of these research groups, although less than before. But that is also not enough. For example, many of us in the university, students and faculty in staff, are part of the Sanctuary Movement [1] in the city. As well, I work with a Literacy Program in Santa Cruz and I teach English to immigrants who need to learn it for survival. These many little things I do are not a social movement, but they keep me connected in place. I think that movements in place, connected with other movements in place, makes us have a greater impact. We become great because we connect. I think my ideas, and as much as possible my actual life, are about making connections.

One person only has one life, so you do some things well and some things poorly. But you stay with the trouble, and you try to let your ideas, which are themselves practices. It’s not like ideas are here and practices over there, the making of knowledge is a practice.

AA: I find very thought-provoking the idea of understanding political engagement and organization not as a huge, solid and unified movement but as sets of connections, situated strategies, assemblies, and multiple situated alliances located. However, I’m wondering if these alliances could actually happen outside the State and how they could materialize large-scale infrastructure projects, such as water supply, public education, etc. To what extent are these ideas linked to, for example, autonomist movements that question the very oppressive and colonial existence of the State?

DH: Outside these institutions. I mean, I agree with you, I think it is necessary this happen simultaneously. Nobody can do everything, but we can know about each other and we can make alliances where we can, as well as how we can disagree with others when necessary.

I think it’s very important to work within and also to work outside, and sometimes in antagonism with the university. To have a certain sense of humor; to have some patience towards antagonism so that it is not understood as the end of the world. Antagonism can generate new ideas. And it’s very important if forces outside the university put pressure on the university, for example. So I actually think it is very important not to have a purified idea about where politics happen. Politics happen just about anywhere people make them happen.

We are in partial alliance and partial conflict. For example, Angela Davis, who was in my department of the university for many years. She initiated a group back in 1990 called Women of Color in Conflict and Collaboration. I join and support this idea: in conflict and collaboration.

AA: This makes me think of “friction”, a metaphor Anna Tsing suggests to understand the diverse and conflicting social interactions and encounters across differences that make up our contemporary world. Friction not necessarily thought as resistance but as an interaction that defines movement, cultural form and agencies through which hegemony is constantly being made and unmade.

DH: Exactly. Anna Tsing is really wonderful. Her concept of generative friction points to the need to rub ourselves against others. I mean, cooperation is all well and good, but sometimes you need friction. Without the friction, it becomes too insular, too nice, right? It’s important not to be nice all the time. But that doesn’t mean a particular person has to do all of that because we have different sensibilities, different capacities for conflict and we need each other.

Portada del más reciente libro de Donna Haraway.

AA: The next question is about reproductive justice, which is a topic very present in your last book Stay With the Trouble. Since we know that women’s reproductive freedom and justice are in tension with the demands of patriarchy, racism, colonialism, and capitalism. In the face of the environmental crisis and the general absence of reproductive and sexual rights, what does a feminist and decolonial exercise of reproductive freedom in solidarity with other species look like?

DH: I think that is an urgent question. I am heartened that many of us are asking the same. What does it already look like and what else is to be done? Radical questions. So, there are achievements that are clear, and remain clear. For example, that human beings must not be coerced into either having or not a child. That coercion in all its forms must be resistant. And that coercion is sometimes subtle, it’s usually structural, it’s often economic. These remain if one thinks in terms of collective justice and not just reproductive rights.

Reproductive justice also means housing and food, the capacity and right to travel and the capacity to engage in knowledge-making systems. I’m avoiding the word “education” because it’s so liberal, haha!, the right to travel. These are all reproductive rights, this is reproductive justice, particularly for women of color who more than thirty years ago insisted on that. Afro-descendant feminist abolitionists understood that caring for their relatives and caring for generations are reproductive rights in equidistance to lynching and genocide practices that are part of reproductive injustice.

The ability to care for generations is crucial for reproductive justice. Thus, reproductive rights—in a narrow sense—are commonly understood as access to good contraceptives (of the kind that you really want to use) and access to abortion without coercion either way. So, of course, these are essential reproductive rights, but they are not enough. They aren’t reproductive justice. I believe that two new causes arise within the feminist work for reproductive justice articulated by anti-racist workers, feminists and our allies: begin to think seriously about issues of ecological justice parallel to the numbers of human population that are really difficult. It has been terrifying to think about this because it easily places us in racist positions. It is very easy to be racist if you are thinking about human population issues. But it is necessary to think about it and to take the risk of being wrong.

Many people begin to criticize racial capitalism, reproductive injustice and its impact on the poor population. Its impact on people of color, in particular, especially women of color. Without losing this criticism, we must also begin to think creatively about density, distribution and the number of people on the planet. We must think about all that in an alliance with non-humans. We must think about this as multi-species. We must think about the entanglement of human beings and other beings in the world: the living and the non-living; the dead; the rocks, the waters, the mountains. And we must look to those who have been thinking this way all along. Which often, not always, but often, are indigenous movements; their way of making kin and taking care of kin who are not all human. Certainly, there are populations of people, speaking of the US, who take care of each other kin because of the oppression of families; African American, Latino families, and so forth. I also think LGBTQ people understand about making kin without having to resort to the figure of the baby as the main factor. There are many models, many practices, some old, some new, for understanding about making kin without emphasizing babies, and taking care of babies who actually get born. The actual care of already existing babies as a priority. In other words, being pro-baby, but not pro-reproduction.

I think people are beginning to try to figure out how to talk about this in a multi-species way without separating human beings and everybody else, without separating rights from justice. We don’t know how to do that yet. There are structural reasons for us not to know how to do that. But I feel a little bit of encouragement.

Ilustración de @electralouis. Imagen vía su cuenta de Instagram

AA: I agree, talking about density population numbers is very risky especially if inequality is not taken into account. In addition, in the context of Mexico and its colonial history, it is a problematic perspective if we consider the policies and practices of population “control” through forced sterilization, a very common practice in Mexico and other Latin American countries. From 2001 to today, the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH for its acronym in Spanish) has documented several cases of this abuse in various ways in rural clinics across the country.

DH: And these are all old histories…

AA: Crossed by internal colonialism…

DH: From the State, and from up: from the class-structure society, from the history of simulations’ and the anti-indigenous policy. All of which has come to bear on women’s bodies. An example is population control, policies, and practices with contraceptive means that are not under the control of women. So I think a feminist demand must be contraceptives under the control of women. Means to control the reproduction that women want and will use; men too, but women first. We must not fail to prioritize these types of demands. People in the communities understand how number growth is not innocent, it is not simple. Not that this is just an external idea.

So, how do people want to deal with this? How do we want to collaborate and cooperate with that? How do we control the migration instrumentalized by colonial logic that strips communal territories to give way to development under the interests of the state and capital? We, as academics and critical thinkers, have knowledge tools—good critique—but we don’t have good policies to deal with problems. I believe that migration policies are really urgent in terms of generational politics: the right to migration in parallel to the fight against migration due to poverty and violence. Therefore, the practice of reproductive justice could be to address forced migration, not just who gets birth control. Without detracting from either aspect.

AA: What other struggles are linked to the exercise of reproductive justice or reproductive freedom? I’m thinking of all forms of forced life, for example in the industrial agricultural complex…

DH: I think it’s really interesting that human numbers on Earth are related to the J-curve, [2] that famous increase of numbers from the end of World War II to now. Plus it happened at exactly the same time as forced life of industrial agriculture, industrial animal production, intensification of mining, extraction, and intensification of land conversion. Modification of the land, through dispossession and undermining of land rights, through legal and non-legal means. These processes are simultaneous, they are co-temporary.

I think of all of us who have been born since World War II, the ones who have been produced by force growth. Moved off the land, moved away from the control of the integrity of communities. Moved into situations where either the care of children is impossible or where another child is necessary to be able to pay for our land tax. Forced reproduction has been a practice that has produced the kind of human numbering crisis we are in. It’s about choice — I think choice is an important word and I don’t want to discard it. However, to think about reproductive choice is to reduce, but to think about forced reproduction is not the type of need that will be addressed by the population control program. At the same time, communities and people must have access to healthy and affordable contraceptives.

Shoshanah Dubiner, Endosymbiosis, tribute to Lynn Margulis, 2012. Image via www.cybermuse.com

AA: Also, what about all the traditional contraceptive methods that are not mediated by allopathic medicine? These are situated technologies that are often erased or discarded when public health systems impose their own methods instead of integrating these local technologies in the apparatus…

DH: Yes, strengthening the community apparatus. But, I think people need and want both. Sometimes traditional apparatuses don’t work very well, and sometimes they do. I think that people are capable of inquiry and capable of asking if these are appropriate circumstances now. Who still has this knowledge and how do we strengthen them? Who wants access to a health clinic, or do we want both? And how do we get it on our terms?

AA: The last question is concerned with a potential intersection or friction between identity politics and the cyborg. Identity politics are usually aimed at claiming greater self-determination and political freedom for marginalized groups by understanding the distinctive nature of each group and questioning typifications imposed from outside, rather than organizing only around belief systems or party affiliation. However, in recent years a reactionary discourse of identity has emerged that perceives race, gender, and sexuality as highly appreciated essences, which define themselves and justify themselves, by reinforcing the binary class/identity approach, giving rise to a stifled political imagination in which identity-based politics can only be conceptualized within a (neo)liberal-capitalist logic. That means identity as the starting point and arrival of the political, instead of being considered part of the work of building meaningful and constructive solidarity between the oppressed groups. In the face of the binarisms on which Western ontology is built (man/woman, nature/culture, human/animal or human/machine) you propose a transhumanist hybridization called cyborg. Where would identity and minority politics stand from a cyborg horizon?

DH: I never called it transhumanist. I avoid these words because they become contaminated so fast. I tend to invent words because those other kinds of words like transhumanist or posthumanism really bother me. This is still human-centered; nevertheless, I’m not against a certain kind of small aged humanism.

Identity politics can become very separatist, fast, and pure. On the other hand, I try to not be an absolutist. I/dentity politics has a place in the practices that I want to see flourish. That is important, to come together with people who recognize and like each other to affirm histories, stories, and identities in connection with others. Identities must be recrafted in connection so that identity politics don’t become a mode of separatism but a mode of situating. We are here, not everywhere. I mean, this history is not all stories. We certainly care about this history, but it’s in connection with what other people care about. How do we find the contact zones to get together? I tend to think that way. Rather than to condemn identity politics.

———

Andrea Ancira (Mexico City, 1984) is a writer, editor, and researcher whose practice is situated at the crossroads of art, politics and experimentation, as a place of (un)learning. She has facilitated formal and informal study platforms on Critical Theory and Marxism, Politics of the Archive, Sound Ethnographies and Communal Practices in museums, universities and independent art spaces such as UNAM, Museo Universitario del Chopo, SOMA, Villa Vassilieff, Beta-Local, Instituto 17, Estudios Críticos, Casco Art Institute, Aeromoto, Biquini Wax EPS and Cooperativa Cráter Invertido.

Since 2011 she has participated in various initiatives organized or in dialogue with the struggles of the National Assembly of Environmental Affected People (ANAA); the Permanent Peoples Tribunal (TPP) and women of the CNI (National Indigenous Congress) and the CIG (Indigenous Council of Government) in Mexico. She has worked as a researcher at the Ministry of Culture in Mexico, as a curatorial assistant at the University Museum of Contemporary Art (MUAC) and as associate curator at Centro de la Imagen. In 2018, she worked as Editorial and Project Coordinator of Buró-Buró, co-coordinated ICI’s Intensive Curatorial Program in Mexico City and participated in the School of Art Criticism of La Tallera/SAPS. Since 2016, she co-created the feminist editorial platform tumbalacasa.

According to its website, the Sanctuary Movement is “a growing movement of immigrants and over 1100 faith communities doing what Congress and the Administration refuse to do: protect and stand with immigrants facing deportation.”

It consists of the graph of a population that grows exponentially at first and suddenly collapses.

Comments

There are no coments available.