03.01.2022

From September 9, 2021 to January 21, 2022 at the Museo de la Filatelia, Oaxaca

Dear Someone:

When we first started to dig in the archives of Mail Art, a question immediately appeared for us and has travelled with this exhibit to this day, when we are finally showing you some of the undusted materials. Where does one begin to excavate an international network of Mail Art that, by the 1970s and 80s, counted with multiple points of entry and exit, and which was not organized around a nuclear center but dispersed in a series of decentralized nodes? Giving another face to a globalizing process dominated by markets, Mail Art established a dynamic system of international artistic connectivity nurtured by a series of exchanges coming from diverse geographic and ideological territories. In a brief period of time, a wide array of aesthetic and political questions travelled through local, regional, and global circuits. Margaret Randall, editor of the bilingual poetry magazine El Corno Emplumado/ The Plumed Horn, referred to this global network as “a world within another world, one without geographical borders or entry requirements.”

A manifest rejection of the art world’s conventional models of production, circulation, and promotion were behind the efforts of Mail Art to redefine cultural borders. It is clear that, by the early 1970s, the Mexican artistic field was ripe for such explorations. On the one hand, publications of international scope that were in place since the 1950s had allowed artists to network with peers such as the Brazilian Noigandres group. On the other hand, the political experience of 1968 resulted in the fact that the younger artists began to organize themselves into autonomous collectives and groups. The same dissident spirit motivated them to explore politically engaged artistic languages, in line with colleagues in South America using conceptual art to confront military regimes and political repression. Here, Mail Art operated as the material network that brought them all together: an independent circuit created and managed by the artists themselves that allowed for multiple forms of association. Participants such as César Espinosa, Araceli Zúñiga and Leticia Ocharán claim that Mail Art ought to be described as a “system of distribution and circulation of artistic messages.” Through Mail Art, participants could advance political ideas and experiment with marginal media (the postcard, the photocopy, the fanzine). Or they could test collaborative pieces that defied the logics of individual originality and prestige, choosing instead the copy, the reproduction, or the drift. Furthermore, the correspondence or “gift” proposed a mode of exchanging art that challenged the inscription of art in the market. These exercises extended the horizons of conceptual art, propagating emerging practices such as performance, artist books, or visual poetry.

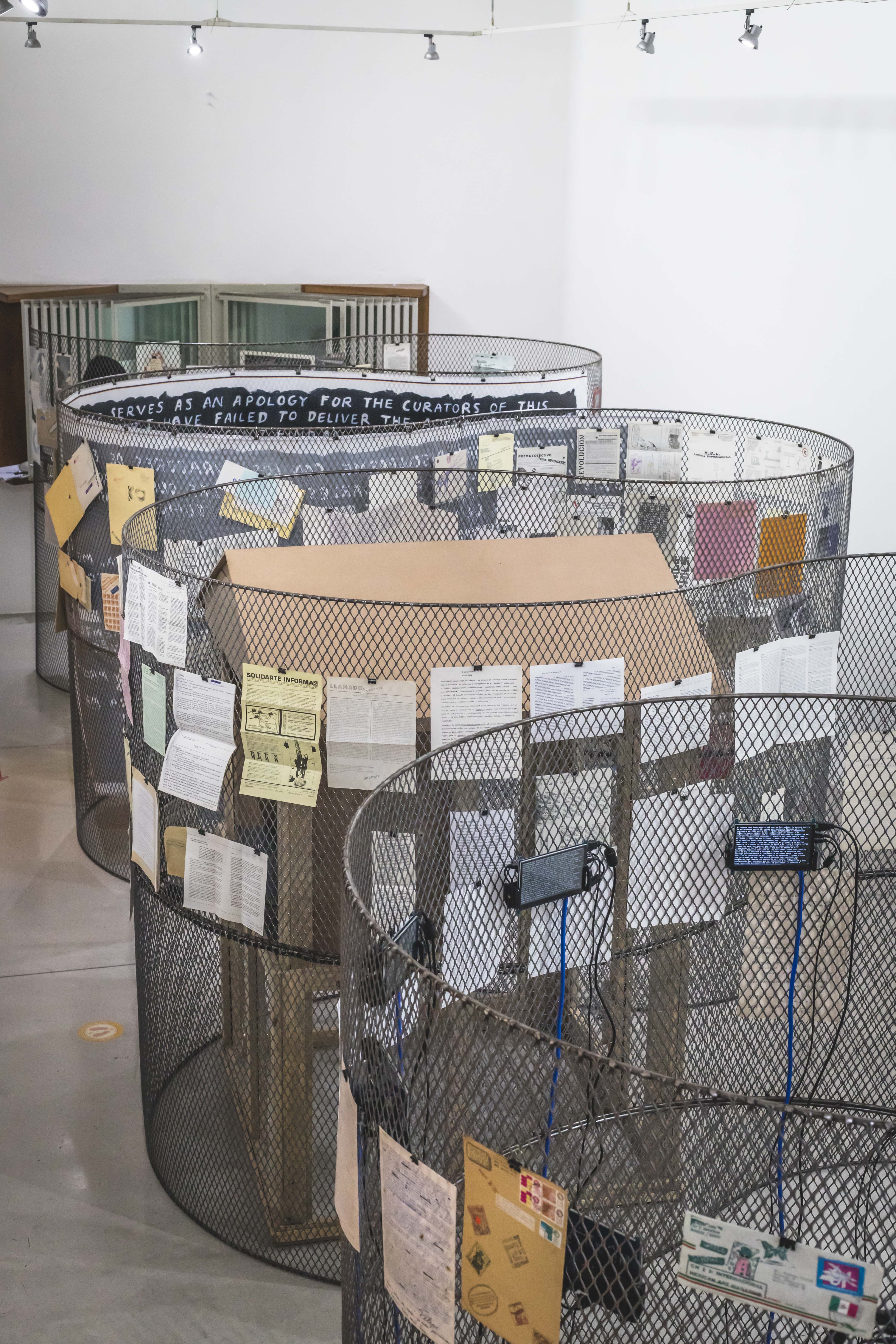

The pieces that were exhibited in fairs, biennales, ephemeral events, or other events constitute only a fraction –a minimal one– of the aesthetic and political proposal of Mail Art. There is no question that Mail Art required collective coordination, a collaborative spirit, and a strong desire to experiment and transform. That is why Ulises Carrión insisted that, from that point on, the strategy behind the organization and circulation of an art piece was not a circumstantial factor, but an intrinsic characteristic of the piece itself. The local, regional, and transnational networks established by Mail Art have to be understood as part of its conceptual process in general. Therefore, when inquiring on the Mexican segment of the Mail Art network, we have asked ourselves how to present a critical cartography of Mail Art that can help us imagine new routes of critical inquiry and artistic praxis. Following Brian Larkin, who claims that an infrastructure is “matter that allows for the movement of other matter,” in this exhibit we aim to dig up the scaffolding of that infrastructure called Mail Art, both in a material and discursive sense.

Hidden Cartographies aims to show that many of the inquiries behind the design and practice of the Mail Art network are all but obsolete today. Therefore, the archaeology of its circuits implies tracking the hidden cables that lead from the past to the present and from the present to the past, showing the evolution and relevance of some of Mail Art’s original concerns. This way, along with the archive, the exhibit presents contemporary pieces that make evident the echoes between Mail Art and our present reality, a few clues that begin to draw possible future itineraries. Inside the universe of cartographic practices, we agree with the geologist when she claims that the past is inscribed in the present. But so do we agree with the archivist who unburies the past to explain the present. And also with the science fiction writer who cannot help but see in the present the scattered signs of the future.

With affection,

Someone else.

A Appropriation

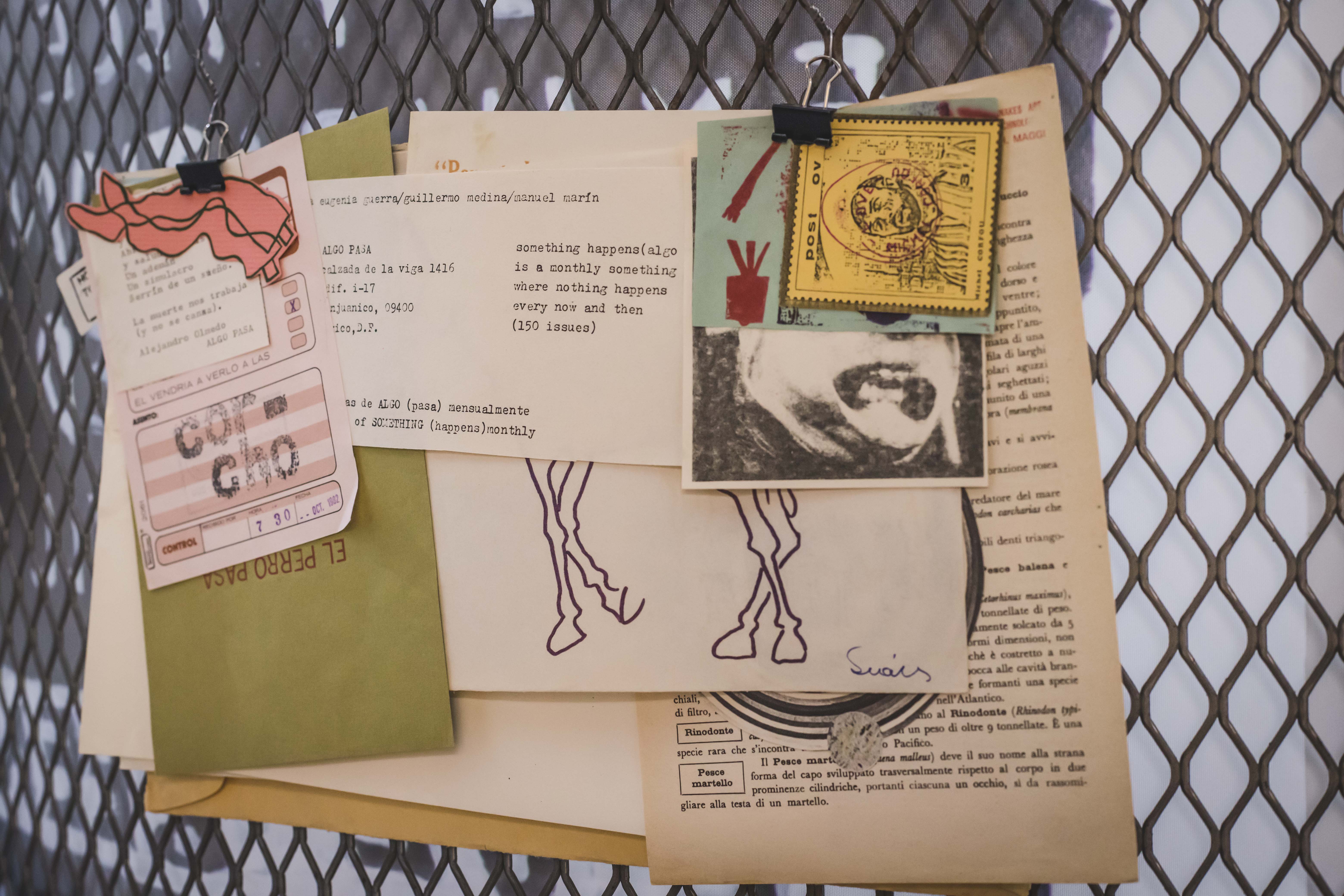

In the beginning there was appropriation. Scattered efforts emerged in the Americas and Europe in order to set up an international network of mail art on the cracks of the postal system, like an organism slowly growing inside another one, using its channels, vehicles, mechanisms, and logistics. The result was a network of artistic exchange that operated almost in clandestine fashion through the postal infrastructure. Conscious of this, artists celebrated this tactical appropriation by means of what Craig J. Saper once called “intimate bureaucracies.” If postal exchange was the point of Mail Art, every single thing that allowed for the exchange to happen and that left a mark of its journey in space and time could be considered a nuclear element of the art piece. Envelopes were more than simple coverings, ink marks played with border controls, postage stamps allowed artists to experiment with the miniature. According to Saper, these “intimate bureaucracies” worked as signs of recognition between artists, a signal that both the sender and the receiver belonged to a deterritorialized community called Mail Art.

B Composition

Conscious that the participants in Mail Art were also the creators, managers, and administrators of a horizontal network of artistic communication, soon enough, artists had to take a step back and ask themselves how they had got there and what exactly was Mail Art. Was it the same thing in the Brazilian dictatorship than in France or England, behind or in front of the Iron Curtain? Inspired by cybernetic feedback loops, artists exchanged manifestos, ideas, and theories that offered divergent explanations of the origins, objectives, and directions of Mail Art. Ray Johnson’s “Correspondence School,” Fluxus’ “Eternal Network,” or the circuits of Latin American concrete poetry were all possible departing points, “alternative genealogies” (Gilbert) for a network that in fact had multiple simultaneous origins.

In Mexico, after the student movement of 1968, one could hear of the collective organization of young experimental artists into a series of autonomous “groups.” One could also hear that some of these young artists (Felipe Ehrenberg, for instance) established the first links with the Mail Art network and began to filter address books and open calls to Mail Art events. Soon enough, many of the “groups” became nodes in a network that allowed them to open up local, regional, and global lines of communication. Collectives specifically devoted to Mail Art such as Aquí or Colectivo-3 (later reorganized into Post/Arte) appeared on the scene. These participants wrote their own manifestos and theories. They also attempted to establish formal associations at the local and regional level. At the same time, artists with similar political or conceptual inquiries (performance, happenings, visual poetry) were establishing their own circuits within the network, continuously redrawing the shifting map of Mail Art.

C Transmission

Because it operated on the side of traditional art institutions, the Mail Art network had to be maintained, updated, and expanded by the artists themselves. The invention of circulation and exhibition infrastructures that allowed Mail Art to become public was essential. Mail artists in Mexico organized events of different kinds, from collective exhibitions such as Salón Independiente to the International Biennales of Visual Poetry. They were attempting to show in these events the collective panorama of Mail Art, its diversity, and plurality. They also had to design their own communication apparatus in the form of posters, invitations, and catalogues.

To sustain the mobility of Mail Art and the continuous updating of the network, different groups began producing periodical bulletins that followed the tracks of experimental poetry magazines sent through the mail such as FILE, Schmuck, or The Plumed Horn. Araceli Zúñiga and César Espinosa’s bulletin Post/Arte did not only circulate open calls to collective events or organized debates on Mail Art, it also published bulletin issues specifically dedicated to visual poetry and other contemporary aesthetic expressions happening in particular countries throughout the world. Manuel Marín’s group established the magazine-envolope Algo Pasa (the group opted to reproduce all of the collaborations received for a magazine issue; they created a series of identical envelopes or packages with the reproduced materials inside and sent an envelope to all of those interested in receiving the magazine). These publications made sure to maintain the local nodes of the Mail Art network active and updated.

D Collaboration

The essential premise of Mail Art was to open up routes of artistic collaboration through the postal system. For more than two decades, the circulation of open calls to participate in Mail Art events around the world ensured the emergence of multidirectional exchanges. There were in the network nodes of low intensity: occasional participants and sporadic collaborations. But there were also well established channels that hosted a significant amount of postal activity. Artists and groups involved in Mail Art defined many different modalities of exchange, collaboration, and collective creation. Its most intimate form was the personal correspondence between two artists, a correspondence that allowed its participants to experiment with the codification and decodification of postal messages. But there were also collective modalities of exchange through open calls that established a theme and a mechanism to participate freely. In these cases, the participations sent by different individuals from around the world were exhibited together as a single piece. That was the mechanism behind collaborative pieces such as the Poema Colective Revolución (Revolution: a Collective Poem), the Pon un objeto cotidiano aquí (Place a daily object here), or the Aquí (Here) postcards. Independently of the modality, feedback was the main ingredient of Mail Art, an element that could adopt different forms: an answer, an intervention, a citation, a forwarded message… All of these actions defined conceptually the material act of the postal exchange. In the end, Mail Art was a language in itself, a system of codes that any participant could employ in order to establish different kinds of correspondence with peers from around the world.

Works Cited

Espinosa, César, Leticia Ocharán and Araceli Zúñiga. “México ¿Posmodernismo sin vanguardia?” In César Espinosa y Araceli Zúñiga, La perra brava: arte, crisis y políticas culturales. Mexico: UNAM/STUNAM, 2002: 119-131.

Gilbert, Zanna. “Genealogical Diversions: Experimental Poetry Networks, Mail Art and Conceptualisms,” caiana 4 (2014): 1-14.

Larkin, Brian. “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (2013): 27-43.

Marcín, Mauricio. “Arte correo en un libro.” In Mauricio Marcín (editor), Arte Correo. Barcelona: RM, 2011.

Randall, Margaret. “Carta a Arnaldo Orfila Reynal.” Margarett Randall Papers. Center for Suthwest Research, University of New Mexico.

Saper, Craig J. Networked Art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

Yépez, Heriberto. “La poética de Ulises Carrión.” In Ulises Carrión, Montones de metáforas. Mexico: Malpaís, 2019.

Museo de la Filatelia de Oaxaca

Calle de la Constitución #201

Centro Histórico, Oaxaca de Juárez

C.P. 68000, Oaxaca, México.

Teléfono: 951 514 2375

Curated by Pedro Ceñal Murga and Alfonso Fierro

Museography by Estudio Fi

Graphic Design by Jackie Crespo

Thank you Lorena Botello, Natalia Brizuela, César Espinosa, Natalia de la Rosa, Ana García Kobeh, Daniel Garza Usabiaga, María Eugenia Guerra, Mauricio Guerrero, Martha Hellion, Alejandra Kurtycz, Magali Lara, Mauricio Marcín, Alejandra Moreno, Clemente Padín, Elva Peniche, Araceli Zúñiga and the Museo de la Filatelia de Oaxaca’s team for your help.

Project funded by

Programa de Fomento y Coinversiones Culturales del FONCA, Mexico.

Patronato de Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico.

Museo de la Filatelia de Oaxaca, Mexico.

Comments

There are no coments available.