22.09.2018

By Germano Dushá, São Paulo, Brazil

September 7, 2018 – December 9, 2018

White-label Bienal

At the beginning of September, the first edition of the Bienal de São Paulo was opened to the public after the coup d’état, which in August 2016 resulted in the impeachment of the then President, Dilma Rousseff. During this period, Brazil experienced its most heightened political turmoil in recent history and, currently, it is in the closing stages before the scheduled date for its next elections, which will be the most complex, tense, and chaotic dispute since redemocratization. Under a coup government capable of destroying any progress in the social and cultural fields over the last few decades, we have observed an escalation of general, state, and targeted group violence—in turn increasing poverty and inequality. Against this backdrop marked by a staggering instability, discourses of hate linked to a blatant fascism and a liberal, simplistic, and deceptive project, which have not had success anywhere in the world, are openly promoted.

It is in this context that Brazil produces, week after week, its most dreadful images, whose aesthetical elements are reproduced in the broadcasts and publications made through digital medias—Brazil being one of the countries most connected to the internet. The dance which invades the news programs and timelines informs us about the assassination of Marielle Franco, city councillor, woman, black, and well-known human rights activist; about conservative attacks articulated in order to coerce and silence artistic activities; about police massacring dozens of street dwellers in an act in the centre of São Paulo worthy of medieval times; about a plane crash involving a minister of the Supreme Court; about the President—unpopular and notoriously corrupt—using arms in order to buy the silence of an accomplice in prison; about countless cases of femicide and savage attacks of transvestites; about an expresident being acclaimed by the people minutes before his surrender to justice after a questionable criminal process; about the barbarities of the war promoted by a military genocide intervention in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro; about a candidate running for presidency attacked with a knife in the middle of an electoral campaign event; etc. The signs of time are extensive and tough… it becomes difficult for art to cope with so much power.

The organizers of the 33rdedition of the Biennial don’t appear to believe in the necessity of engaging with the heat and pressures beyond the Pavilhão Ciccillo Matarazzo, where it has created its own microclimate bubble.

Under the will of questioning a certain automatism which has taken the design processes of the major global exhibitions of the last few decades, in which the role of the curator gained more visibility upon choosing and articulating questions, the plan of this year, lead by the Spanish Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro, presented itself without any noticeable uniqueness or any individual aspect which could favour its identification. The argument is that the modus operandi of the last editions was important, but it brought serious problems, such as the centralization of power in one figure and hindering the diversity of ideas and pushing the artists into a cloudy territory, of minor importance and conditioned to illustrate a thesis or a predefined concept. In order to respond to this crisis of the curatorial model, the biennial departs from a discourse which is deliberately generic. Without specific desires or interests, it opts for a kind of non-identity.

Named Afinidades afetivas, in a pleonastic conjunction making a reference to the title of the novel “Afinidades eletivas” 1809) by Goethe and from the thesis “De la naturaleza afectiva de la forma” (1949) by Mário Pedrosa, the exhibition with approximately 100 artists does not have a clearly defined theme. Instead of an author proposal, it seeked to employ its core energy in order to think about its own organisation, concerned primarily with the possible experiences of the public in relation to the works and the effects which those result in. Therefore, the focus is in line with the reading that Goethe and Pedrosa make, on the phenomenon’s which absorb our attention and the performing potential of art for individual emancipation and social transformations, regardless of formal or narrative elections.

In practice, the direction of this edition took two fundamental decisions: to depart from a tabula rasa visual programming and to draw up a fragmented operational model. The first point reveals itself in a communication which is easily confused with the institutional identity of the Biennial Foundation itself. Upon making simple use of the Helvetica font in lower case, used exhaustively everywhere since the mid-twentieth century, the objective was to have the least possible interference in the content; to make something which serves for everything, without indicating anything at the beginning. In this way, it focuses more on the number 33 than on its own title. The second point manifests itself in a framework with twelve individual projects chosen by Pérez-Barreiro, the “general curator”, and seven collective expositions organised by invited artists—called ‘artist curators’, which also include their own works. Therefore, it sought to establish few and isolated choices, and to give a larger part of the exhibition space to certain artists in order for each one to work in total autonomy. As such, naturally, there is no single path to traverse or understand the biennial; in that fragmentation, every moment arises with complete freedom and, clearly, suitably enclosed.

Curatorship seeks only to be responsible for the given faculties of the artists. It resembles, in a certain way, the activity of white label businesses that develop products or services to be labelled and resold in many different ways by other people, without the commitment of being directly involved in the final result.

Individual Projects

The group of twelve exhibitions is made up of eight commissioned projects, a historical project, and three posthumous expositions of Latin American artists active in the 1990s who died prematurely and who, despite their importance, remain unknown. In addition, what they have in common is the temporality which they share in relation to the preferences of the chief curator.

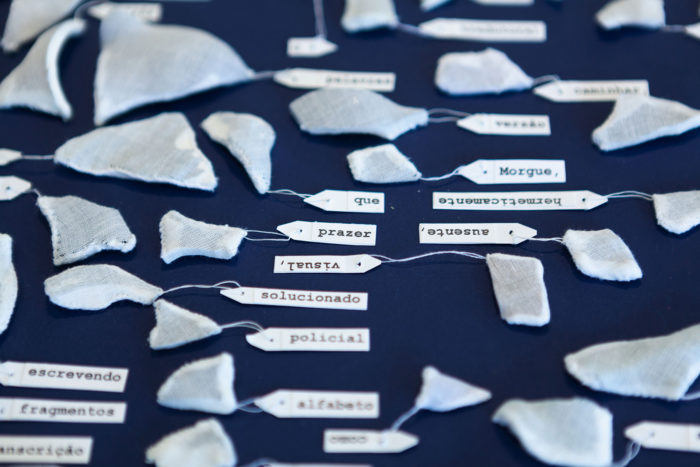

The exhibitions vary from dull and compressed exhibition of the series of paintings by Siron Franco (1947) related to the radioactive disaster arising from the spillage of cesio-137, which took place in the city of Goiânia in the year 1987, to a proposal by Luiza Crosman (1987) which reunites post internet furniture—with obvious North American and European influence, interventions in the building and in the audio guide of the exposition, such as dialogues with the Biennial Foundation in order to discuss and attempt to shape aspects of the action system of the institution. This critical willpower is present in two other commissioned projects: the astute film by Tamar Guimarães (1967), about the essay of an adaptation of a novel Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas (1881), by Machado de Assis, occurring in the physical and organizational fields of the Biennial, and the network of actions by Bruno Moreschi (1982), which seeks to create a parallel archive in order to think critically and to intervene in the production, dissemination and analysis of the documented registers, archivists and communications generated by the 33rdedition. Although nothing makes the temper rise, they are considerable initiatives that think about the institutional problems from within.

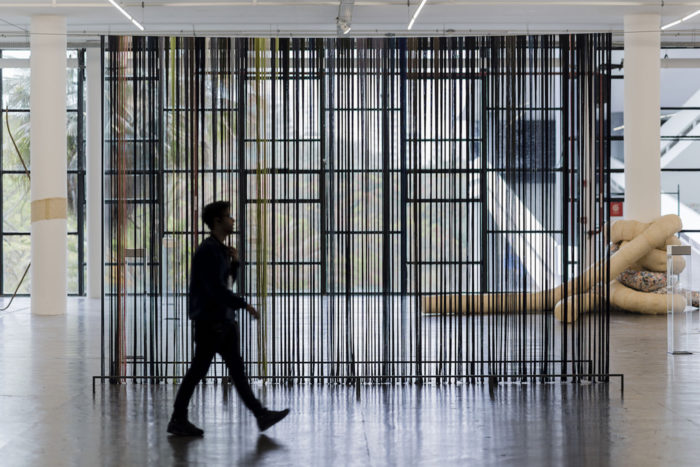

In the section of the tributes, there is a small retrospective by Lucia Nogueira (1950-1998), a Brazilian who was living in London. Her works are about intense and unusual materialistic psychological relations between objects, spaces, and situations. It is a work conscious of the volatility of the forms, signs, and mental states, especially guided by a Brazilian psyche, which makes it capable of offering good provocations for these days. It is regrettable that it is exposed in a museum device—a mix of a catwalk, an exposition of an art fair and a prison unit—which blocks the public from relating with the works through a body play, an essential element for the artist.

Collective exhibitions

Both in the museums layout of the exhibitions as well as in the individual curatorial ideas, the complete absence of conversation is made explicit between the “artist-curators” during their design process. Each one did what they wanted in their limited space.

The ground floor, for example, is occupied almost completely by the exposition sentido/común by the Spanish Antonio Ballester Moreno (1977), which brings together artists from different generations, works of their grandparents and other references in order to look over very superficially the relations between ecology and culture, challenging dualistic thinking such as nature vs modernism, intuition vs science, aesthetics vs function, popular art vs erudition. It is a good cover letter for a biennial that emerged passionate for pleasant gestures and not for the intensity of the risk, for the broad proposal and not by a complex discourse. Right above is the exhibition organised by the Brazilian Sofia Borges (1984), with many of her works, her friends, and references, such as Tunga (1952-2016) and Sarah Lucas (1962), and some of the artists associated with the Museu do Imaginário Inconsciente de Nise da Silveira such as Adelina Gomes (1916-1984). With a labyrinthine exhibition space, made with thick walls and heavy velvet curtains, it presents countless photographs, paintings, and sculptures, seeming more like an immense dissertation-installation of the artist herself about her ideas regarding the limits of culture, language and representation.

In the middle, as part of the exhibition curated by Wuru-Natasha Ogunji (1970), an American living in Nigeria, Apariciones stands out, washing rituals by the South African Lhola Amira (1984)—an urgent action of production of knowledge and treatment with the oppressed indigenous peoples of the damaged soil like Brazil—, and the sculptures of a specific place by the Lebanese Youmna Chlala (1974), which engage with the physical and conceptual properties of the columns by Oscar Niemeyer. In a similar way, a big sculpture by the Bolivian Elba Bairon (1947) comments directly on the modern building in which the exposition O pájaro lentois located, by the Argentine Claudia Fontes (1964). Finally, the façade created by the Uruguayan Alejandro Cesarco (1975) gleams, with works by the brilliant Sturtevant, one of the most recent of the entire biennial, who nevertheless, died in 2014 at the age of 89.

On the top floor, the works of the Swedish Mamma Anderson (1962) and of the Brazilian canon Waltercio Caldas (1946) are located side by side, each one enclosed in its own fairly traditional white cube. The first exhibits various paintings of the artist curator, the only woman in the show, together with pieces by important artists for their formation, such as the Polish Ladislas Starevich (1882-1965) with the pioneered animation La venganza del camarógrafo—made in 1912 with insect’s cadavers—iconic Russian paintings by Henry Darger (1982-1973) and seven of his compatriots. The second, carpeted, full of white walls and crammed with works—the majority being of Waltercio himself—refers immediately to the excesses and the hypoxia of the art rooms from the past century or from the art fairs intended for the secondary market, which throw together an array of objects and modernist paintings. Just one woman is involved, the Venezuelan of German origin Gego (1912), and in stark contrast with another eighteen men. Here nothing has been understood regarding the importance of making visible art history beyond the gaze and the masculine canon. As a common ground, everyone makes themselves present through formal spiritual exercises which happen in a range of approximations with the aesthetical interests, and with the work it is clear, of the curator artist.

Affects and Effects

Contrary to the emotional vision of this biennial, it is difficult to not be provoked by the cataclysm which moves closer to us, desiring to find only what is at the height of the spirit of the times. Even more complicated is trying simply to cut out the influence, for better or for worse, which social networks exercise in our lives, as the curator also points out without deepening into the topic. It is symbolic that the exhibition has opened its doors in a week the following on an extremely tragic Sunday, in which the country witnessed, completely astounded, the fire of the Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro. The images of the flames devouring its base will fade from the memories of the Brazilians with difficulty over the next few years, and the idea that a large part of their diverse archive, whose importance was immense, now is ashes, will forever leave distressing marks on our social imaginary.

A biennial in this Brazil of the second decade of the twenty-first century can only be worthwhile in the urgency and in the excitement in which it is conceived; understanding it as an opportunity to liberate strong imaginations and carry out projects of rare magnitude, which only in that context can come to light. In the most alarming hour, upon dressing a kind of translucent cape, the plan of this Biennial doesn’t even affirm its existence nor experience cancelling it. On the one hand it lets the game so open and blunt, whilst on the other, it seems to insist on what are tired of seeing: it is basically confined to the expositional field of the pavilion, it is based on personalised selections, it presents a concept sustained on bibliographical references and it talks in a metadiscourse that only appeals to specialists.

In spite of being burocratically competent, risks and opinions are not taken, therefore nothing is revised nor radicalised. It only delivers what can be on the reliance of any museum or gallery of any scale, in any part of the world. In that sense, it distances itself from the potential of the institution over its public function. In short, although quite rightly it refuses the automation of the totality in order that nothing is on top of the singular experiences of each fragment, it touches very little on the vital enigma that governs the affects, of which Goethe speaks to us. It touches even less on the possibility of being taken by the transforming and revolutionary power of the artistic experience, as Pedrosa proposes.

Germano Dushá (Serra dos Carajás, 1989) is a writer, critic, curator and cultural producer based in São Paulo. He holds a BA in Law and a postgraduate degree in Art: Criticism and Curatorship. He works mainly with independent art projects and curatorial experiments, and has contributed to many publications. He has cofounded the projects Fora; Coletor; Observatório; um trabalho um texto; e BANAL BANAL.

Comments

There are no coments available.