10.10.2016

by Cristiana Tejo, São Paulo, Brazil

September 10, 2016 – December 11, 2016

When the São Paulo Biennial was established in the 1950s, Brazil was considered a country of the future. Besides its welcoming atmosphere for immigrants, a fast and steady rhythm of economic growth and industrialization made the country a fertile terrain for new and modern utopic experiments. The Biennial was originally conceived by an Italian, industrial businessman who designed it to put Brazil into the gravitational zone of the international art scene and update local artists and audiences about the latest international art debates. São Paulo incarnated the spirit of cultural renewal and with a batch of new institutions like the Biennial, the Museum of Modern Art (MAM-SP) and MASP (Museu de Arte de São Paulo), it reclaimed the title of capital city of the arts, even though Rio de Janeiro was still the capital of the country and home to many important artists and thinkers. Brazil was not a consolidated democracy but was trying to move past its legacies of colonialism, and of the slave trade by the progressive implementation of work laws, and the nationalization of petroleum and gas production, among other things. President Getúlio Vargas, who emphasized this process of economic modernization, was a dictator before being democratically elected and some years after his suicide, the country was again under dictatorship. In its almost 200 years of independence, Brazil has only been a democracy for few, short periods.

Now, seven decades after the inauguration of the Biennial and the birth of other cultural institutions that altered the ecology of the arts in Brazil, the street that represents the XX Century in São Paulo and the country, Avenida Paulista, is the epicenter of a swell of conservatism. The wave culminated in a recent, new kind of coup, done without military force and following all the rites as a normal impeachment procedure, but with no crime of responsibility–which is the main cause for an impeachment. The reason for President Dilma Rousseff’s deposition became clear when the deputies dedicated their votes against her to their children, their mothers, God, and their spouses, and not on behalf of public interest. It was evident when the interim President announced his ministries and we could see only men: white, straight, and rich, and in the front ground of political power. It was obvious when after dozens of plea-bargaining and a huge investigation against corruption, the elected President Dilma was not mentioned once. It seems that the period where the Brazilian Labour Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores) was in power was a brief concession for affirmative policies and social adjustment by the “owners” of the country even when Brazilian economics had made astonishing developments, and its role in international politics had gained relevance.

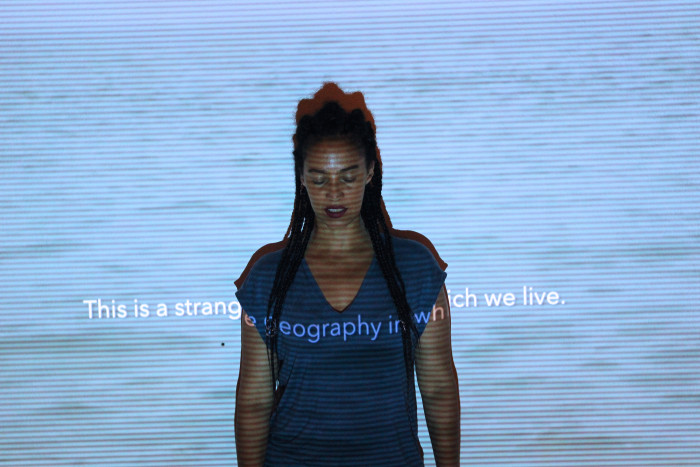

The 32nd edition of São Paulo Biennial opened on September 7, 2016, the day of celebration of Brazil’s independence and a week after the definitive removal of Dilma from office. This evolving political scenario added new layers of meaning to the Biennal’s title Live Uncertainty. In the opening press conference, curator-in-chief Jochen Volz mentioned that the first speech of the new Brazilian President Michel Temer, which started by saying that “the uncertainty was over,” was really just a message for investors and for the financial field, and was in fact an exact counterpoint to the perspective adopted by the Biennal. In President Temer’s view, the newfound certainty was anchored by anachronistic truths and order: no more space and civil rights for the silenced voices of minorities, no more room for the increase of quality in public services, no more emphasis in culture as a catalyst for change, and no more protagonism in the international arena. In short; let’s put things back in “traditional” places, restoring the patriarchal, colonial, and classist order. Suddenly, he positioned a new platform for Brazil that harkened back to the 1960s, or in some cases to the XIX Century.

Alternatively, Live Uncertainty is theoretically based in decolonial thought and sheds light on environmental and epistemological issues; it tries to identify new approaches to knowledge and new ways of dealing with present, global conditions, in a strong dialogue with the previous Biennal curated by Charles Esche. However, questioning and doubt are present not only in the discourse of the show–as in the last biennial–but in the attitudes of the curatorial team specifically regarding the dynamics of the art world.

Departing from the ideas of Portuguese sociologist Boaventura de Sousa Santos, in particular his concept of the “epistemologies of the South,” Volz and his co-curators defy common beliefs about what a Biennial should be, incorporating “denaturalization” as a method. Firstly, they interrogate the current role of the São Paulo Biennial given that the national and international context has changed dramatically since it was conceived, and that the Biennial is not the only way to connect the Brazilian art scene to the hegemonic art world. In fact, it argues that the notion that real art is made in Europe, in the USA and the rest of the modern globe just follows it has long been proven obsolete. So it’s ongoing iteration doesn’t comprise big international names. On the contrary, it presents fresh names of both young artists (Vivian Caccuri, Barbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca, Cristiano Lenhardt, Lais Myhrra, Jorge Menna Barreto, Dalton Paula, Grada Kilomba, only to mention some) and veteran artists that haven’t received proper visibility yet (Sonia Andrade, Gilvan Samico, Bené Fonteles). In this way, it’s curatorial standpoint is that the Biennial is a platform to update the global art world, altering the common understanding of who has to learn from whom.

Secondly, there is an interconnected vision between world ecology and the ecology of the arts, pointing to the fact that, while we discuss the exhaustion of the natural resources of the planet, we are also addressing our own fatigue from certain ways of doing things within the art world. This Biennial is impregnated by minimal gestures and an intimate atmosphere that avoids curatorial pyrotechnics. The standpoint of the proposal also declines sexy and extravagant concepts, thus questioning the sustainability of the anxiety of the new. So, many people may be disappointed by the recurrence of a similar tone and similar preoccupations that were highlighted in previous international exhibitions, such as the 13th Documenta of Kassel, 55th Venice Biennale and in some angles, Esche’s Biennial. Originality is a belief rooted in XIX century, like modern science and positivism also are. However, in the 32nd Biennial of São Paulo, we are in the territory of de-centered perspectives brought by a myriad of critiques that attempt to articulate other forms of knowledge.

Thirdly, there is a visible respect and affection among the curatorial team, the people who work in all levels of the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, the artists, and the audience that can be noticed by the generous scale of the show–less artists, more space–and the care taken with the information about the show that is distributed to a broad public. It may sound like a silly statement, but it is not if we want to be coherent with the theories that we use and the pursuit of fresh approaches towards art and life. It is usual to visit exhibitions that are theoretically based on post-colonial or decolonial discourse, but that in practice are made by people who disregard and mistreat each other, their colleagues, the institutional professionals, and the non-experts. In the ecology of knowledges (another idea of Sousa Santos) there is a respectful process of listening and a consideration of the other’s knowledge and subjectivity in order to surpass the monoculture of scientific knowledge and self-centered worldview. In Santos’ words: “Over the last decades, there has been a growing recognition of the cultural diversity of the world, with current controversies focusing on the terms such of such recognition. But the same cannot be said of the recognition of the epistemological diversity of the world, that is, of the diversity of knowledge systems underlying the practices of different social groups across the globe. However, from anti-capitalist perspective such recognition is crucial. The epistemological privilege granted to modern science from seventeenth century onwards which made possible the technological revolution that consolidated Western supremacy, was also in suppressing other, non-scientific forms of knowledge and, at the same time the subaltern social groups whose social practices were informed by such knowledges. In the case of the indigenous people of the Americas and of the African slaves, this suppression of knowledge, a form of epistemicide (Santos, 1998), was the other side of genocide”. [1]

Instead of the monoculture of scientific knowledge, Boaventura de Sousa Santos suggests an ecology of knowledges, a way of establishing a dialogue in a constellation of knowledges, as all knowledges are incomplete. In terms of the art world, respecting the other is a way of altering Western conceptions of professionalism, where such an act contains the possibly emancipatory consequence of re-balancing the ecology of the arts.

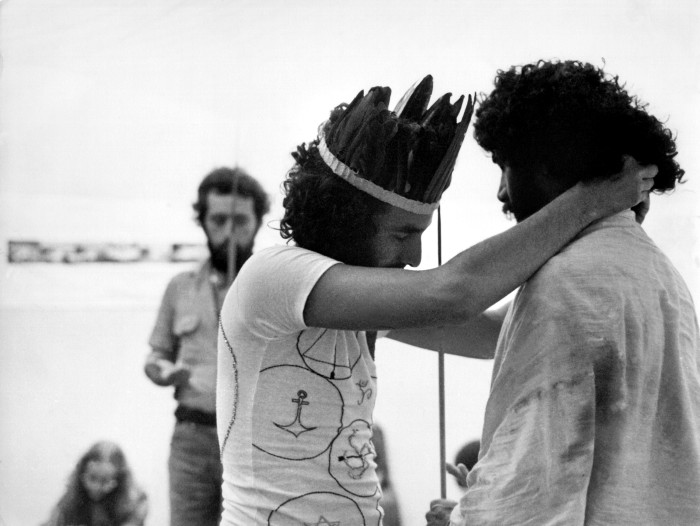

There is an effort in this biennial of gathering different spaces of speech, just as we have been noticing in some of the major exhibitions of the last two decades, which depart from post-colonial and decolonial perspectives. I would like to mention the presence in the São Paulo Biennial of one of the most important projects in Brazil addressing indigenous matters: Vídeo nas Aldeias (Video in the villages). The project started in 1986 as an initiative of indigenist film-maker Vicent Carelli and aims to empower native groups from all regions of Brazil via the usage of video. After some workshops, indigenous groups are encouraged to produce their own videos at the same time that they see others’ production. The methodology of the project breaks with the hegemonic Western white gaze, as each community choses how to present themselves and what they consider relevant to highlight –as a political and ethnic strategy. Concomitantly, there is a meaningful exchange within groups that are separated geographically but who face similar issues, thus turning video into an important tool for treatment and discussion of shared causes. Nowadays, there are circa 70 films produced in the last 30 years that can be seen in the project website and for the first time the archive is shown in an art exhibition. After so many perspectives considering native people as objects, this project allows them to be subjects, as they always were.

Notes:

[1] Santos, B. d. (2007). Beyond abyssal thinking. From global lines to ecologies of knowledges. Eurozine. Accesed on September 23rd 2016, http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2007-06-29-santos-en.html

Comments

There are no coments available.