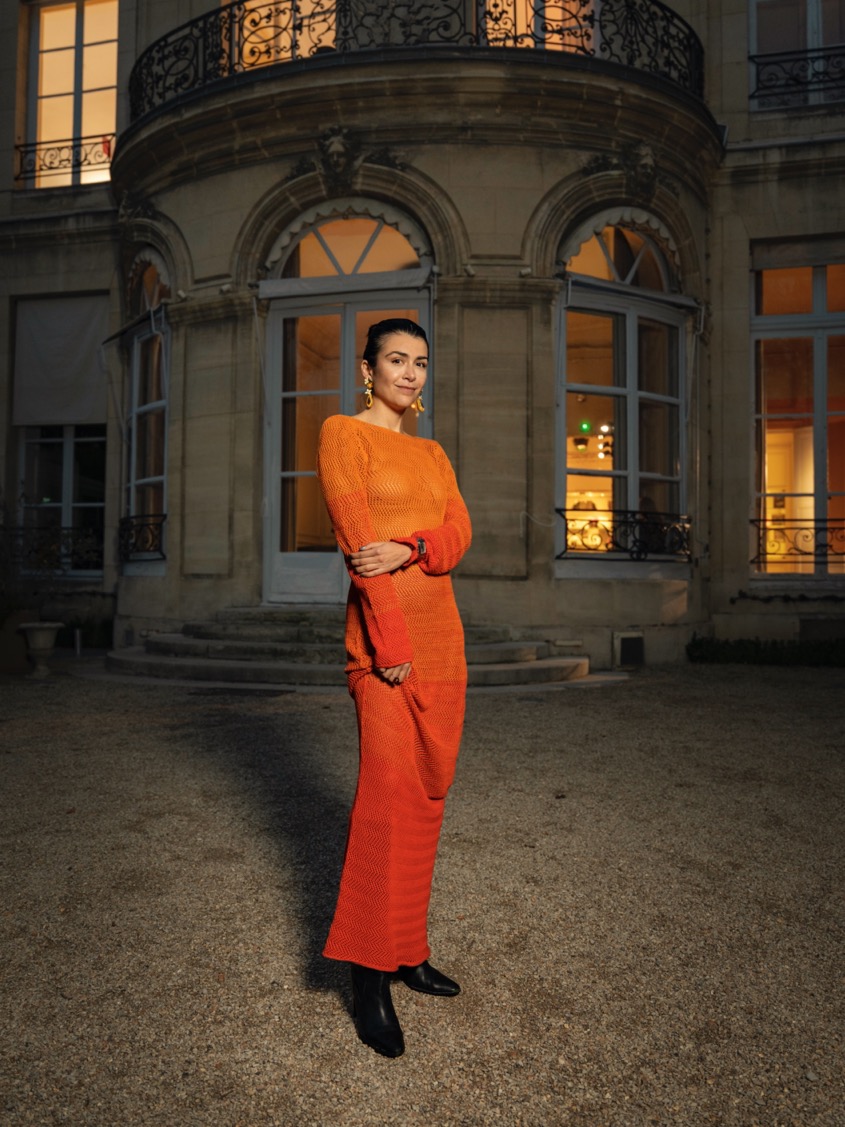

Can a Latin American art fair in Paris escape exoticism without abandoning the market? From the Maison de l’Amérique Latine, MIRA Art Fair operates at the intersection of cultural translation, colonial memory, and the need to build a market that does not reproduce old hierarchies. In this conversation with Manuela Rayo, founder of the fair, we discuss identity as a site of dispute, authenticity as a political strategy, and the ever-present risk of turning “Latin American” into yet another market label. An interview about narrating ourselves from within, unsettling the center, and sustaining a transcontinental project without concessions.

MIRA’s existence confirms that Latin American art has acquired both symbolic and economic value within the European circuit. The fair moves between the emancipatory gesture of asserting identity and the risk of becoming just another label in the catalog of the global art market. We spoke with Rayo about these tensions, the challenges of leading a transcontinental project, and the need to build a cultural bridge that does not reproduce long-standing power imbalances.

Verónica [V]: Founding a fair dedicated to Latin American art in Paris implies an act of cultural translation. From where is Latin America being translated for a European audience?

Manuela Rayo [MR]: Inevitably—although I don’t like to admit it—Latin America is still seen in Europe through a halo of exoticism: a place where it’s always hot and the party never ends. Showing our artistic scene allows us to complicate that image, blur clichés, and reveal nuances. I like to think of this relationship in terms of our languages: Spanish or Portuguese in relation to French. They are similar, almost sister languages, but never identical. That small distance is where what’s interesting emerges: dialogue and curiosity.

V: Art fairs are, at their core, commercial devices. At the same time, presenting Latin American art in Paris inevitably raises questions about colonial history. How does MIRA reconcile the need to build a market with the possibility of sustaining a critical discourse around coloniality, inequality, or cultural extractivism?

MR: For me, one does not exclude the other. MIRA was born with a dual objective: to build a cultural bridge between Latin America and Europe, and to generate a solid market for our artists. Both missions are equally important. Being conscious of our colonial, unequal, and complex past is what gives us identity and legitimacy. It’s not about denying the wound, but about transforming it into discourse and into our own aesthetic language. I deeply believe that authenticity sells: when we speak from what hurts or unsettles us, the result carries strength and truth. Add a strong narrative, clear communication, and a tireless team, and that’s the formula.

V: A frequent critique of the so-called “boom” of Latin American art is that institutions in the Global North exhibit it without changing the conditions of production, distribution, or valuation. How does MIRA engage with Latin American contexts and the countries of origin of its exhibitors and artists?

MR: MIRA has a fundamental advantage: we are Latin American women telling our own story. Our team—Colombian, Mexican, Uruguayan, Argentine—makes all the curatorial decisions. We do work with French collaborators, yes, but the decisions are grounded in a Latin American perspective. That changes everything. It’s not the same to be observed from the outside as it is to narrate ourselves from within. That gaze brings legitimacy, empathy, and real knowledge of the contexts. Every artist, every gallery, every performance is selected with respect and with a profound sense of responsibility: to show the diversity and power of our voices without simplifying them.

We are still limited by resources, but each edition is a step closer to broader and fairer representation. This process would not be possible without key people such as Noelia Portela, who has played a fundamental role in shaping this vision.

V: How do you prevent MIRA from functioning as an “identity niche” within the European art market—that is, a space where Latin American art is consumed solely as an aesthetic category?

MR: It’s a question I ask myself constantly. I don’t want MIRA to be “the exotic fair,” but rather a fair defined by quality, thought, and risk—one that also happens to be Latin American. At the same time, we have to acknowledge it: yes, we are a niche, and we’re proud of that. In France, African, Asian, or Middle Eastern art scenes have strong, well-established platforms; the Latin American scene, by contrast, remains underrepresented. Very few galleries in Europe work with artists from the region. That lack of visibility is precisely what justifies MIRA’s existence.

Each year, we work to build a narrative that celebrates our identities, presenting a diverse, complex, and contemporary Latin America—where identity is not a stereotype, but a point of departure.

V: Latin America is not a homogeneous region. How is it decided, from Paris, what is included and what is left out of the category “Latin American art”? Which areas do you feel are still underrepresented, and why do you think that is?

MR: That diversity is what makes Latin America so fascinating. We share roots and a history marked by colonization, but not all countries are represented in the same way. Stronger economies, such as Mexico or Brazil, have a consolidated presence, while other contexts—like Cuba, Peru, or Paraguay—remain less visible.

And yet, talent and creative power exist everywhere. In our first edition, for example, Cuba had an incredible representation of artists and curators. I believe it is our responsibility to keep expanding the map, to show what is seen and what is not yet seen. Nothing should be left out.

V: What are the main challenges you’ve encountered in leading a project that seeks to give value to Latin American art? What can we expect from the future of the fair?

MR: All of them! (laughs). Paris is a wonderful city, but it’s also a saturated and highly competitive market, with a cultural structure very different from ours. Bringing projects from Latin America involves complex logistics, limited resources, and a great deal of perseverance.

But those challenges are also opportunities: in such a demanding context, only what is truly distinct and authentic manages to stand out. MIRA keeps growing. Each edition is more solid and more ambitious, moving closer to its original dream: to build a space that not only shows Latin American art, but engages with the rest of the world on equal footing.

MIRA’s existence confirms that Latin American art has acquired both symbolic and economic value within the European circuit. The fair moves between the emancipatory gesture of asserting identity and the risk of becoming just another label in the catalog of the global art market. We spoke with Rayo about these tensions, the challenges of leading a transcontinental project, and the need to build a cultural bridge that does not reproduce long-standing power imbalances.

Verónica [V]: Founding a fair dedicated to Latin American art in Paris implies an act of cultural translation. From where is Latin America being translated for a European audience?

Manuela Rayo [MR]: Inevitably—although I don’t like to admit it—Latin America is still seen in Europe through a halo of exoticism: a place where it’s always hot and the party never ends. Showing our artistic scene allows us to complicate that image, blur clichés, and reveal nuances. I like to think of this relationship in terms of our languages: Spanish or Portuguese in relation to French. They are similar, almost sister languages, but never identical. That small distance is where what’s interesting emerges: dialogue and curiosity.

V: Art fairs are, at their core, commercial devices. At the same time, presenting Latin American art in Paris inevitably raises questions about colonial history. How does MIRA reconcile the need to build a market with the possibility of sustaining a critical discourse around coloniality, inequality, or cultural extractivism?

MR: For me, one does not exclude the other. MIRA was born with a dual objective: to build a cultural bridge between Latin America and Europe, and to generate a solid market for our artists. Both missions are equally important. Being conscious of our colonial, unequal, and complex past is what gives us identity and legitimacy. It’s not about denying the wound, but about transforming it into discourse and into our own aesthetic language. I deeply believe that authenticity sells: when we speak from what hurts or unsettles us, the result carries strength and truth. Add a strong narrative, clear communication, and a tireless team, and that’s the formula.

V: A frequent critique of the so-called “boom” of Latin American art is that institutions in the Global North exhibit it without changing the conditions of production, distribution, or valuation. How does MIRA engage with Latin American contexts and the countries of origin of its exhibitors and artists?

MR: MIRA has a fundamental advantage: we are Latin American women telling our own story. Our team—Colombian, Mexican, Uruguayan, Argentine—makes all the curatorial decisions. We do work with French collaborators, yes, but the decisions are grounded in a Latin American perspective. That changes everything. It’s not the same to be observed from the outside as it is to narrate ourselves from within. That gaze brings legitimacy, empathy, and real knowledge of the contexts. Every artist, every gallery, every performance is selected with respect and with a profound sense of responsibility: to show the diversity and power of our voices without simplifying them.

We are still limited by resources, but each edition is a step closer to broader and fairer representation. This process would not be possible without key people such as Noelia Portela, who has played a fundamental role in shaping this vision.

V: How do you prevent MIRA from functioning as an “identity niche” within the European art market—that is, a space where Latin American art is consumed solely as an aesthetic category?

MR: It’s a question I ask myself constantly. I don’t want MIRA to be “the exotic fair,” but rather a fair defined by quality, thought, and risk—one that also happens to be Latin American. At the same time, we have to acknowledge it: yes, we are a niche, and we’re proud of that. In France, African, Asian, or Middle Eastern art scenes have strong, well-established platforms; the Latin American scene, by contrast, remains underrepresented. Very few galleries in Europe work with artists from the region. That lack of visibility is precisely what justifies MIRA’s existence.

Each year, we work to build a narrative that celebrates our identities, presenting a diverse, complex, and contemporary Latin America—where identity is not a stereotype, but a point of departure.

V: Latin America is not a homogeneous region. How is it decided, from Paris, what is included and what is left out of the category “Latin American art”? Which areas do you feel are still underrepresented, and why do you think that is?

MR: That diversity is what makes Latin America so fascinating. We share roots and a history marked by colonization, but not all countries are represented in the same way. Stronger economies, such as Mexico or Brazil, have a consolidated presence, while other contexts—like Cuba, Peru, or Paraguay—remain less visible.

And yet, talent and creative power exist everywhere. In our first edition, for example, Cuba had an incredible representation of artists and curators. I believe it is our responsibility to keep expanding the map, to show what is seen and what is not yet seen. Nothing should be left out.

V: What are the main challenges you’ve encountered in leading a project that seeks to give value to Latin American art? What can we expect from the future of the fair?

MR: All of them! (laughs). Paris is a wonderful city, but it’s also a saturated and highly competitive market, with a cultural structure very different from ours. Bringing projects from Latin America involves complex logistics, limited resources, and a great deal of perseverance.

But those challenges are also opportunities: in such a demanding context, only what is truly distinct and authentic manages to stand out. MIRA keeps growing. Each edition is more solid and more ambitious, moving closer to its original dream: to build a space that not only shows Latin American art, but engages with the rest of the world on equal footing.