What does it mean to curate a biennial in a territory shaped by colonial violence and a memory that has yet to fully sediment? This text approaches the 24th Paiz Art Biennial as a space of friction, where the metaphor of the tree of life enables—and at times fails—to think through the relationships between body, territory, and history from Guatemala.

Curating a biennial in the era of biennialization entails a particularly complex task. Biennials seem to be expected to condense a multiplicity of meanings into a single gesture, as if nothing could be left outside them: identity, body, memory, language, spirituality, territory, colonization, future. An international biennial tends to operate simultaneously as diagnosis, archive, and horizon, offering a broad reading of a deeply unequal world. This demand for totality signals the place the biennial occupies today as a space of collective projection. Faced with these excessive expectations, its power does not lie in encompassing everything, but in what it manages to activate: opening questions, rehearsing relationships, sustaining frictions.

Yet, what are the implications of curating a biennial in and from Guatemala? What does it mean to curate a biennial today? What responsibilities are activated when the curatorial gesture does not take place in a hegemonic art capital, but in a territory marked by colonial violence, Indigenous genocide, structural inequality, and a memory that has yet to fully sediment? How can a biennial be conceived within the Central American context?

With 48 years of history, the Paiz Art Biennial has been one of the main platforms for inserting Guatemala into the global contemporary art map. Throughout its editions, it has brought together artists from different geographies, consolidating itself as an international meeting point. In its 24th edition, titled The Tree of the World curated by Eugenio Viola—an Italian critic and curator whose practice has focused on performance, the body, and experience—the biennial takes as its departure point the concept of the tree of life: a symbol that cuts across multiple cultures, articulating the spiritual and the material, the individual and the collective, life and death, heaven and earth.

The tree as metaphor intertwines and takes root; it promises connection, continuity, regeneration. It is an archetype of creation and origin, a powerful image for thinking about existence and collective identity. However, its symbolic power also carries a risk: that of becoming a comfortable abstraction capable of accommodating any discourse. How can spirituality and memory be addressed in Guatemala without neutralizing their political charge? How can the past be prevented from becoming an aesthetic motif stripped of conflict? What tree grows here?

The Tree of the World finds some of its most powerful moments in artworks that engage the body, memory, and Latin American territory as contested spaces that activate political, affective, and historical relations. In Tierra arrasada [Scorched Earth], a performance by Carlos Martiel, the artist stands naked beside an iron sculpture bearing the word GENOCIDE and invites the audience to lift it together with him. The action seeks to collectively bear the weight of mourning, while referencing not only the massacres of Mayan peoples in Guatemala but also the ways such violence reappears and is reactivated in Palestine. The burden also points to shared responsibility for the conditions that allow certain massacres to persist and be administered as part of the contemporary order.

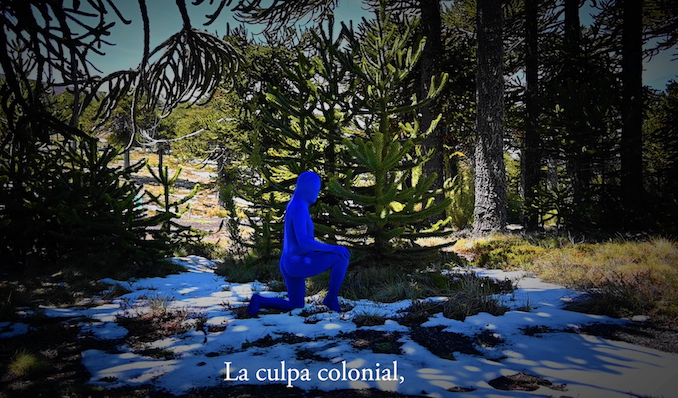

On the other hand, Seba Calfuqueo presented the video installation Culpa [Guilt]. Through the artist’s body and a written narrative, the work exposes the relationship between the colonization of Ngulu Mapu—the Mapuche territory annexed by the Chilean state—and the devastation of nature. The piece dismantles the symbolic violence embedded in the so-called “Pacification of the Araucanía,” revealing how state language operates as a mechanism of erasure and legitimation of dispossession. In this intersection of body, territory, and writing, colonization appears as an ecological and political wound that continues to produce effects in the present, resonating with other histories of occupation and extractivism across Latin America.

In contrast to colonization, other works move toward the possible. In Los deseos nuestros [Our Desires], Jeff Cán Xicay shifts the question of identity toward the right to desire and to the future. His installation stems from a collaboration with Kataj, a collective space for community-based thought and memory in which the artist has grown and participated actively. The work consists of a series of phrases expressing desires articulated by the community itself: “we will not be afraid,” “genocide will end,” “women and men will have courage,” “we will have dignity.” These statements activate a shared temporality in which the future is neither utopia nor promise, but a practice articulated from everyday life.

The idea of the future finds a different echo in Documentación de envíos [Documentation of Shipments], by Jorge de León, which addresses displacement. An improvised raft supports a concrete block carved with Mayan faces and drawings that trace its possible journey from Guatemala to the United States. The drawn landscapes introduce a dreamlike, almost fragile dimension that sustains imagination as a motor for traversing hostile territories, where fantasy operates as a form of survival.

From a more intimate place, the work of Colombian artist Luz Lizarazo unfolds. In Ambular, she presents a series of drawings that articulate a personal cosmogony, the result of years of reflection on femininity and on what spiritually sustains us as human beings. Without resorting to grand gestures or overtly politicizing territory, the work proposes a sensitive perspective that dialogues with the metaphor of the tree of life from the realm of the everyday and the affective.

However, despite its achievements, the biennial also reveals the inevitable tensions and fissures that traverse any curatorial process of this scale. Even with the diversity of artists’ backgrounds and the intention to construct a multinational narrative, some works prove problematic in how they situate themselves within the Guatemalan context. In front of certain works, the question arises: why continue to summon the colonizing gaze as a source of legitimacy for a biennial located in Guatemala? How can territory be thought without neutralizing the political potential of the past through its aestheticization?

The problem is not what is represented, but how and from where. By detaching history and memory from the conditions that produced them, certain works reduce the Guatemalan context, weakening its critical force. This is particularly evident in the case of Orlan’s work, which rather than engaging in dialogue with Mayan culture, seems to reinscribe asymmetries and reactivate colonial imaginaries that the biennial itself seeks to question.

The French artist is known for her long trajectory in body and performance art—from live surgeries that challenge beauty standards to digital self-hybridization series that merge her own face with diverse iconographies as a strategy against the hegemonic aesthetic canon. Her work belongs to a critical tradition concerning image, beauty, and the body as social construction. Yet within the Guatemalan context, this operation fails to activate meaningful reflections on local colonial and racial violence; instead, it reproduces a form of symbolic appropriation that invokes Mayan iconography from a Western body, as if such images could be used as a visual surface without confronting the material conditions of domination and dispossession that persist in the present.

In Diego Cibelli’s case, the friction lies not in form but in meaning. The drawing is technically impeccable. However, it depicts a shared banquet where figures from Roman and Mayan worlds coexist, fused in a kind of historical fantasy. This symbolic confusion is not innocent. By juxtaposing the imaginary of the Roman Empire—historically a paradigm of expansion, domination, and conquest—with Mesoamerican Indigenous cultures, the work flattens historical differences and erases power relations. The banquet becomes a dangerous metaphor: it suggests a horizontal encounter where none existed. In the Guatemalan context, where the consequences of colonization remain material and not merely narrative, this operation is deeply unfortunate.

The case of Kite is particularly complex, precisely because she is an artist, composer, and researcher with a solid and widely recognized practice. Her work has consistently explored computational media and performance, integrating artificial intelligence systems with Indigenous knowledge since 2017. Her performance at the biennial’s opening, staged in the ruins of La Recolección Church in Guatemala City, felt surprisingly restrained and predictable. Built around dream narratives accompanied by classical music—live violins and cellos—it retreats into an aesthetic introspection that fails to activate a critical relationship with the site. The choice of a Western classical musical language produces an effect of distancing, and the performance ultimately functions as an aesthetic interlude, frankly boring.

The tensions running through The Tree of the World place the Paiz Art Biennial in a fertile space for discussion. In a context like Guatemala—where history has not been repaired and colonial wounds continue to produce material effects—a biennial cannot aspire to neutrality. Its relevance lies in its capacity to make these frictions visible and to interrogate their conditions. Which narratives make sense in this territory? From where are they articulated, and whom do they address? Which bodies, memories, and futures are activated—and which are left out—when thinking the global from this context?

The biennial does not offer univocal answers to these questions, but it does clearly expose the risks and possibilities of such an attempt. Its successes show that it is possible to activate relationships between body, territory, and history. Its frictions, by contrast, reveal how easily colonial imaginaries can be reinscribed, even when the intention is to open other readings.

Within this unstable balance, the Paiz Art Biennial reaffirms its relevance as a necessary critical space. Not as a device meant to resolve everything, but as a platform that insists on how to situate an international biennial in Guatemala. The Tree of the World works when this question remains in the foreground: when works take root in Latin American territory and the context acts as an active interlocutor. In the more international crossings, this specificity sometimes dissolves; yet it is precisely in this back-and-forth that the biennial rehearses—not without risk—ways of thinking the global from this context. Asking what tree grows here is a way of recognizing the vitality of a biennial that continues to grow.

Photographies by Sergio Muñoz

Courtesy of Fundación Paiz

Curating a biennial in the era of biennialization entails a particularly complex task. Biennials seem to be expected to condense a multiplicity of meanings into a single gesture, as if nothing could be left outside them: identity, body, memory, language, spirituality, territory, colonization, future. An international biennial tends to operate simultaneously as diagnosis, archive, and horizon, offering a broad reading of a deeply unequal world. This demand for totality signals the place the biennial occupies today as a space of collective projection. Faced with these excessive expectations, its power does not lie in encompassing everything, but in what it manages to activate: opening questions, rehearsing relationships, sustaining frictions.

Yet, what are the implications of curating a biennial in and from Guatemala? What does it mean to curate a biennial today? What responsibilities are activated when the curatorial gesture does not take place in a hegemonic art capital, but in a territory marked by colonial violence, Indigenous genocide, structural inequality, and a memory that has yet to fully sediment? How can a biennial be conceived within the Central American context?

With 48 years of history, the Paiz Art Biennial has been one of the main platforms for inserting Guatemala into the global contemporary art map. Throughout its editions, it has brought together artists from different geographies, consolidating itself as an international meeting point. In its 24th edition, titled The Tree of the World curated by Eugenio Viola—an Italian critic and curator whose practice has focused on performance, the body, and experience—the biennial takes as its departure point the concept of the tree of life: a symbol that cuts across multiple cultures, articulating the spiritual and the material, the individual and the collective, life and death, heaven and earth.

The tree as metaphor intertwines and takes root; it promises connection, continuity, regeneration. It is an archetype of creation and origin, a powerful image for thinking about existence and collective identity. However, its symbolic power also carries a risk: that of becoming a comfortable abstraction capable of accommodating any discourse. How can spirituality and memory be addressed in Guatemala without neutralizing their political charge? How can the past be prevented from becoming an aesthetic motif stripped of conflict? What tree grows here?

The Tree of the World finds some of its most powerful moments in artworks that engage the body, memory, and Latin American territory as contested spaces that activate political, affective, and historical relations. In Tierra arrasada [Scorched Earth], a performance by Carlos Martiel, the artist stands naked beside an iron sculpture bearing the word GENOCIDE and invites the audience to lift it together with him. The action seeks to collectively bear the weight of mourning, while referencing not only the massacres of Mayan peoples in Guatemala but also the ways such violence reappears and is reactivated in Palestine. The burden also points to shared responsibility for the conditions that allow certain massacres to persist and be administered as part of the contemporary order.

On the other hand, Seba Calfuqueo presented the video installation Culpa [Guilt]. Through the artist’s body and a written narrative, the work exposes the relationship between the colonization of Ngulu Mapu—the Mapuche territory annexed by the Chilean state—and the devastation of nature. The piece dismantles the symbolic violence embedded in the so-called “Pacification of the Araucanía,” revealing how state language operates as a mechanism of erasure and legitimation of dispossession. In this intersection of body, territory, and writing, colonization appears as an ecological and political wound that continues to produce effects in the present, resonating with other histories of occupation and extractivism across Latin America.

In contrast to colonization, other works move toward the possible. In Los deseos nuestros [Our Desires], Jeff Cán Xicay shifts the question of identity toward the right to desire and to the future. His installation stems from a collaboration with Kataj, a collective space for community-based thought and memory in which the artist has grown and participated actively. The work consists of a series of phrases expressing desires articulated by the community itself: “we will not be afraid,” “genocide will end,” “women and men will have courage,” “we will have dignity.” These statements activate a shared temporality in which the future is neither utopia nor promise, but a practice articulated from everyday life.

The idea of the future finds a different echo in Documentación de envíos [Documentation of Shipments], by Jorge de León, which addresses displacement. An improvised raft supports a concrete block carved with Mayan faces and drawings that trace its possible journey from Guatemala to the United States. The drawn landscapes introduce a dreamlike, almost fragile dimension that sustains imagination as a motor for traversing hostile territories, where fantasy operates as a form of survival.

From a more intimate place, the work of Colombian artist Luz Lizarazo unfolds. In Ambular, she presents a series of drawings that articulate a personal cosmogony, the result of years of reflection on femininity and on what spiritually sustains us as human beings. Without resorting to grand gestures or overtly politicizing territory, the work proposes a sensitive perspective that dialogues with the metaphor of the tree of life from the realm of the everyday and the affective.

However, despite its achievements, the biennial also reveals the inevitable tensions and fissures that traverse any curatorial process of this scale. Even with the diversity of artists’ backgrounds and the intention to construct a multinational narrative, some works prove problematic in how they situate themselves within the Guatemalan context. In front of certain works, the question arises: why continue to summon the colonizing gaze as a source of legitimacy for a biennial located in Guatemala? How can territory be thought without neutralizing the political potential of the past through its aestheticization?

The problem is not what is represented, but how and from where. By detaching history and memory from the conditions that produced them, certain works reduce the Guatemalan context, weakening its critical force. This is particularly evident in the case of Orlan’s work, which rather than engaging in dialogue with Mayan culture, seems to reinscribe asymmetries and reactivate colonial imaginaries that the biennial itself seeks to question.

The French artist is known for her long trajectory in body and performance art—from live surgeries that challenge beauty standards to digital self-hybridization series that merge her own face with diverse iconographies as a strategy against the hegemonic aesthetic canon. Her work belongs to a critical tradition concerning image, beauty, and the body as social construction. Yet within the Guatemalan context, this operation fails to activate meaningful reflections on local colonial and racial violence; instead, it reproduces a form of symbolic appropriation that invokes Mayan iconography from a Western body, as if such images could be used as a visual surface without confronting the material conditions of domination and dispossession that persist in the present.

In Diego Cibelli’s case, the friction lies not in form but in meaning. The drawing is technically impeccable. However, it depicts a shared banquet where figures from Roman and Mayan worlds coexist, fused in a kind of historical fantasy. This symbolic confusion is not innocent. By juxtaposing the imaginary of the Roman Empire—historically a paradigm of expansion, domination, and conquest—with Mesoamerican Indigenous cultures, the work flattens historical differences and erases power relations. The banquet becomes a dangerous metaphor: it suggests a horizontal encounter where none existed. In the Guatemalan context, where the consequences of colonization remain material and not merely narrative, this operation is deeply unfortunate.

The case of Kite is particularly complex, precisely because she is an artist, composer, and researcher with a solid and widely recognized practice. Her work has consistently explored computational media and performance, integrating artificial intelligence systems with Indigenous knowledge since 2017. Her performance at the biennial’s opening, staged in the ruins of La Recolección Church in Guatemala City, felt surprisingly restrained and predictable. Built around dream narratives accompanied by classical music—live violins and cellos—it retreats into an aesthetic introspection that fails to activate a critical relationship with the site. The choice of a Western classical musical language produces an effect of distancing, and the performance ultimately functions as an aesthetic interlude, frankly boring.

The tensions running through The Tree of the World place the Paiz Art Biennial in a fertile space for discussion. In a context like Guatemala—where history has not been repaired and colonial wounds continue to produce material effects—a biennial cannot aspire to neutrality. Its relevance lies in its capacity to make these frictions visible and to interrogate their conditions. Which narratives make sense in this territory? From where are they articulated, and whom do they address? Which bodies, memories, and futures are activated—and which are left out—when thinking the global from this context?

The biennial does not offer univocal answers to these questions, but it does clearly expose the risks and possibilities of such an attempt. Its successes show that it is possible to activate relationships between body, territory, and history. Its frictions, by contrast, reveal how easily colonial imaginaries can be reinscribed, even when the intention is to open other readings.

Within this unstable balance, the Paiz Art Biennial reaffirms its relevance as a necessary critical space. Not as a device meant to resolve everything, but as a platform that insists on how to situate an international biennial in Guatemala. The Tree of the World works when this question remains in the foreground: when works take root in Latin American territory and the context acts as an active interlocutor. In the more international crossings, this specificity sometimes dissolves; yet it is precisely in this back-and-forth that the biennial rehearses—not without risk—ways of thinking the global from this context. Asking what tree grows here is a way of recognizing the vitality of a biennial that continues to grow.

Photographies by Sergio Muñoz

Courtesy of Fundación Paiz