A journey through Anri Sala’s latest exhibition at kurimanzutto, where the frescoes become landscapes of compressed time: seconds, centuries, and geological eras coexisting on a single surface. Among passing clouds, millenary marbles, and atmospheres that seem caught in negative, Sala invites us to look more slowly—to observe the intervals between what has just happened and what is about to occur. Here, every crack in the fresco is a fissure revealing history, fragility, and possibility. Each layer of lime, pigment, and aluminum coexists with questions about memory, ideology, technology, and the tensions of a world in constant crisis. What do we see when we look at a painting through a screen? Which images endure over time? And which bodies become trapped—like clouds—inside the stones that hold them? Michelle Sáenz Burrola writes about the work, time, and the act of looking.

I walked into the gallery and made my way through the green room. The artist was moving at full speed. In his hand he held a ring that, to my eyes, looked like a snail leaving behind a metallic, iridescent trail. The gallery’s natural light and the aluminum backing of the frescoes cast a shimmering reflection around them.

Anri Sala’s recent exhibition at kurimanzutto presents a series of frescoes situated between temporal and geological layers. Throughout the walkthrough, the artist poses questions about the personal, historical, and conceptual relationship he maintains with this recent body of work, linking it to his audiovisual practice. Fresco, he says, is a technique that forces you to slow down and does not allow for much expressiveness, since you work on wet plaster and must treat it with great care. These two limitations have allowed him to physically internalize a calmer temporality at a moment of acceleration. His first encounter with fresco painting was as an art student at the National Academy of Arts in Tirana, Albania, in the 1990s, shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union. During this shift in identity, history, and ideology, there was a sense of opportunity as well as a great velocity. Systemic change could only be absorbed through processes that required more slowness; this is why he calls for deceleration through the fresco technique—one he has set in counterpoint to his audiovisual production.

Interval, Temporality

The interval in Sala’s work appears at different scales and moments as a space between two instants: when something has just happened and something else is about to occur. In the artist’s early video works we find Intervista: Finding the Words (1998), in which Sala discovers a 16mm reel in his family home showing his mother participating in a Communist Youth congress decades earlier. The film had no sound, so the artist resorted to lip-reading, working with a school for the deaf that helped him decipher the words his mother spoke during an interview. Years later, in an ideological landscape transformed after the fall of communism, Sala confronts her about those ideals, which have since shifted. In this case, the proposed interval unfolds across decades: How do the ideals we hold transform through our experiences and the political and social changes we live through? What role does ideological consistency play in moments of ruin and catastrophe? How can we preserve ideals tied to a specific historical moment as an act of resistance?

In the works currently exhibited at kurimanzutto, intervals manifest at different temporal scales. In the frescoes, they appear as lapses of seconds: the movement and transformation of clouds as fleeting moments of contemplation; in other cases, they appear as centuries-long intervals through the use of technologies such as fresco painting, analog photography, or celluloid, in contrast with contemporary digital devices like smartphones. Finally, we also see intervals of thousands of years on a geological scale, evident in the marbles embedded in the paintings.

Sliding the Gaze Toward the Clouds

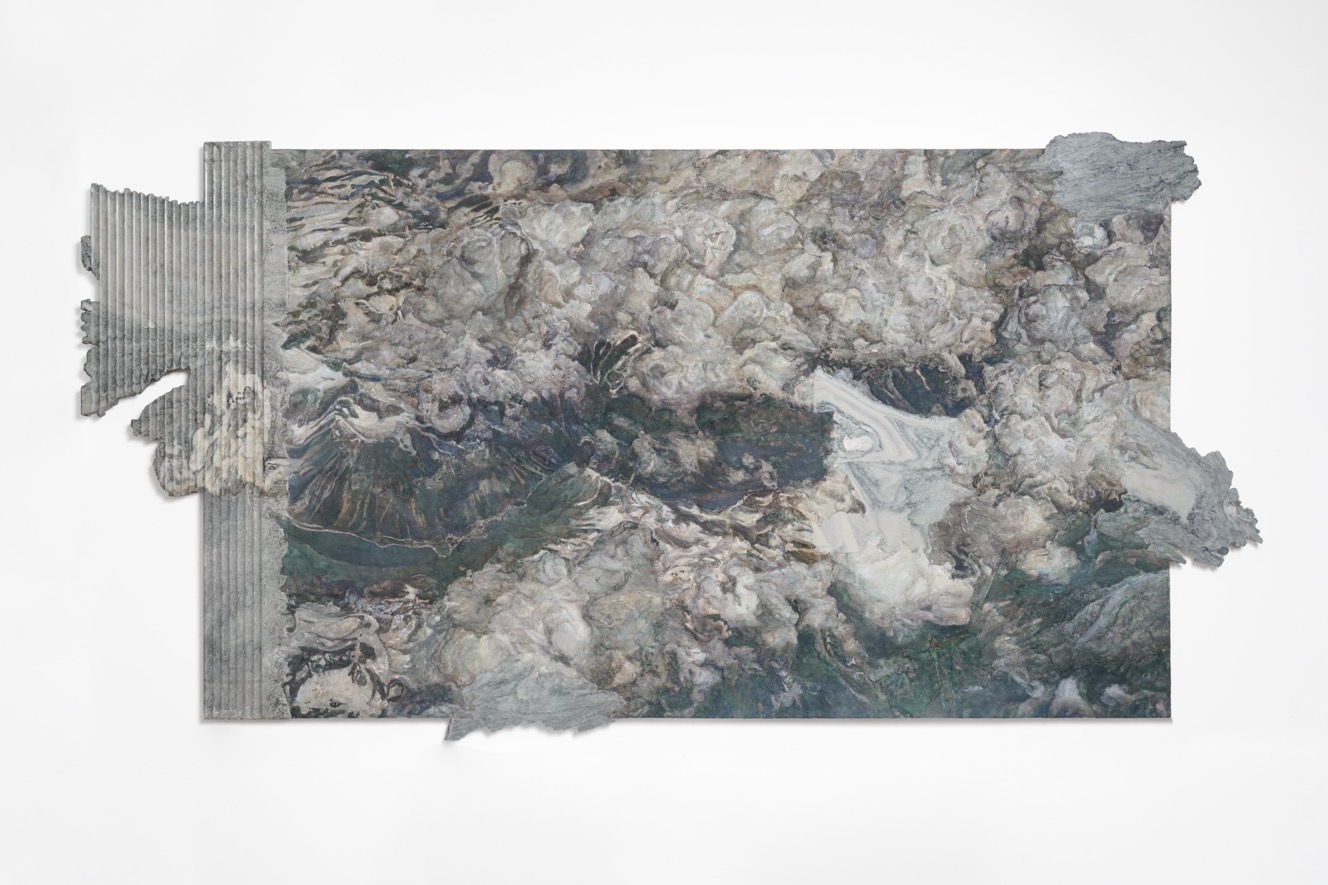

The Surface to Air series reveals shifting perspectives: aerial views and upward gazes. Color exists in the material itself—among layers, indentations, and reliefs. The atmospheres are blue, orange, green, brown, gray; from them emerge moving landscapes where clouds constantly shift. Looking out an airplane window and realizing that you are floating, almost touching water in its gaseous state—vulnerable, and yet held by a nearly unquestioned sense of safety, protected only by technological advancement and the idea of progress.

Tracing vista (STA XXIX, Giornata 1–29) appears as an explosion of the initial atmosphere, a guide that unfolds across transparent layers to map the fresco. It resembles a cartographic study composed of printed stones, currents drawn as lines, and perforations that act as pathways guiding the assembly of the atmosphere.

In Surface to Air XXXII and Surface to Air XXXVIII, we encounter two moments: being above the clouds, and ascending/descending toward a human settlement. In both, millennia-old marbles are inlaid, softening the squared grid of the frame; a space between sea, clouds, mountain ranges, and the faint suggestion of an urban grid at the periphery. Where do these marbles come from? The artist traces their journey from stone formation millions of years ago to a restoration workshop in Naples, where precious marbles gather like a treasure.

In Surface to Air XXXIV, XXXV, and XXXIII, the atmosphere grows drier. They appear as three seconds of video stills—barren earth, a Martian landscape, or the crater of a celestial body. The Tartaruga marbles reveal their cavities leading into the fresco’s interior. These openings confirm that life was once fossilized in them, fading and leaving voids behind.

The series Surface to Air owes its title to the perspective it proposes: observing the atmosphere and cloud movement from the ground upward or from the sky downward. Yet the name also evokes missiles launched from land or sea toward an aircraft or incoming projectile. Today, the global political landscape is in crisis: the rise of the far right, ongoing genocides—uninterrupted by any organization capable of intervening—ecocides, and relentless dynamics of colonial, extractivist, dominant, and erasing violence.

Symbolically, the missile is a rupture that shatters calm. What would happen if that apparent stability were suddenly disrupted by something symbolizing a missile strike? There is no need to imagine it—this is the daily reality of millions across the planet, and through our devices we have access to images of multiple coexisting realities.

In this sense, the serene temporality of cloud movement represented in the frescoes might hold only a few microseconds of contemplation—instants before or after the destabilization of a missile or the bombardment of war images accumulating in our minds.

The materiality of the frescoes intertwines with their content by revealing and contrasting temporal processes—the different rhythms matter requires to take shape. The frescoes consist of layers: the plaster surface, the embedded minerals, and within them a metallic aluminum support holding the image industrially.

Remembering Historical Frescoes

The artist’s historical relationship with painting is evident in both his interest in the medium and his references to frescoes by Piero della Francesca, Fra Angelico, and Masaccio. In Legenda Aurea Inversa (VII, fragment 1), a figure from another time appears. When we encounter it, Sala invites us—through our cellphones—to switch the camera to negative mode in order to discover, on our own devices, colors resembling those of Piero della Francesca. In Cristo Deriso (Fragment 1) the inversion from positive to negative directly recalls Fra Angelico, establishing a dialogue between digital techniques and classical painting. The reflection of natural light from the gallery collides with the fresco’s aluminum backing, creating a zigzagging halo around the piece. Finally, in The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (Inversa), inspired by Masaccio, the two figures—expressing pain and confusion beside the interior of a shell—appear as if newly revealed and seen backlit, like a negative. The faces in the fresco bear textures reminiscent of sand and earth. The fresco process becomes a metaphor for time: lime sets slowly, layer by layer, like the assembly of a video in which moving images are edited without linear narrative, oscillating between flow and rupture. Fresco and video thus share a tension between the permanence of matter and the ephemerality of the image.

Celluloid Against the Light

Our eyes are accustomed to seeing images in positive—but how do we relate to images when they are in negative? During the conversation, Sala mentioned that this translation of colors is not intuitive, making it difficult to decipher the colors painted negatively in the fresco. What reflections arise when we use our phones to view the original colors of paintings presented to us in negative? What happens when we look at a painting through a cellphone?

When visiting exhibitions, we constantly pull out our phones to document experiences or photograph images we want to remember. The choreographic act of placing the phone before the painting—and the device itself distorting the color—allows the image and our bodies to inhabit two simultaneous spaces: virtual and physical.

It is only through a technological mediator, such as a projector or cellphone, that we can see the colors in positive. The exercise of looking at a painting in negative and translating it into positive through our phones reveals an older version of the image. This action underscores the way we live in-and-outside the screen, emphasizing our dependence on technological mediation.

A Fissure to Look Closely

In fresco painting, cracks are inevitable, explained Gianmarco Biele, the artist’s assistant for this project. When I asked about the process, I understood that they result from drying and material reactions; however, I believe these fissures also want to speak. Where do these cracks lead us? How do they translate into our own time? The fissures seem almost imperceptible, yet they insist that we look closely. They ask us to gaze attentively at modernity’s failed promises, to recognize them and reorient ourselves. We stand on the edge of collapse, and it is through these fissures that we can observe, act, listen, and create meaning.

After finishing the exhibition, I stayed in the bookstore getting to know the artist’s work a bit more—page after page, book after book—moving through my body like images in motion. Staying there allowed me to situate the frescoes within a broader interweaving of his practice. When I left the gallery, I thought about the clouds and minerals in the frescoes as I walked among rocks and the sky, as if they were one and the same body. The experience gave me the chance to feel close to what has been there far longer than I have, like an interval, before returning to the chaos of life and the city.

I walked into the gallery and made my way through the green room. The artist was moving at full speed. In his hand he held a ring that, to my eyes, looked like a snail leaving behind a metallic, iridescent trail. The gallery’s natural light and the aluminum backing of the frescoes cast a shimmering reflection around them.

Anri Sala’s recent exhibition at kurimanzutto presents a series of frescoes situated between temporal and geological layers. Throughout the walkthrough, the artist poses questions about the personal, historical, and conceptual relationship he maintains with this recent body of work, linking it to his audiovisual practice. Fresco, he says, is a technique that forces you to slow down and does not allow for much expressiveness, since you work on wet plaster and must treat it with great care. These two limitations have allowed him to physically internalize a calmer temporality at a moment of acceleration. His first encounter with fresco painting was as an art student at the National Academy of Arts in Tirana, Albania, in the 1990s, shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union. During this shift in identity, history, and ideology, there was a sense of opportunity as well as a great velocity. Systemic change could only be absorbed through processes that required more slowness; this is why he calls for deceleration through the fresco technique—one he has set in counterpoint to his audiovisual production.

Interval, Temporality

The interval in Sala’s work appears at different scales and moments as a space between two instants: when something has just happened and something else is about to occur. In the artist’s early video works we find Intervista: Finding the Words (1998), in which Sala discovers a 16mm reel in his family home showing his mother participating in a Communist Youth congress decades earlier. The film had no sound, so the artist resorted to lip-reading, working with a school for the deaf that helped him decipher the words his mother spoke during an interview. Years later, in an ideological landscape transformed after the fall of communism, Sala confronts her about those ideals, which have since shifted. In this case, the proposed interval unfolds across decades: How do the ideals we hold transform through our experiences and the political and social changes we live through? What role does ideological consistency play in moments of ruin and catastrophe? How can we preserve ideals tied to a specific historical moment as an act of resistance?

In the works currently exhibited at kurimanzutto, intervals manifest at different temporal scales. In the frescoes, they appear as lapses of seconds: the movement and transformation of clouds as fleeting moments of contemplation; in other cases, they appear as centuries-long intervals through the use of technologies such as fresco painting, analog photography, or celluloid, in contrast with contemporary digital devices like smartphones. Finally, we also see intervals of thousands of years on a geological scale, evident in the marbles embedded in the paintings.

Sliding the Gaze Toward the Clouds

The Surface to Air series reveals shifting perspectives: aerial views and upward gazes. Color exists in the material itself—among layers, indentations, and reliefs. The atmospheres are blue, orange, green, brown, gray; from them emerge moving landscapes where clouds constantly shift. Looking out an airplane window and realizing that you are floating, almost touching water in its gaseous state—vulnerable, and yet held by a nearly unquestioned sense of safety, protected only by technological advancement and the idea of progress.

Tracing vista (STA XXIX, Giornata 1–29) appears as an explosion of the initial atmosphere, a guide that unfolds across transparent layers to map the fresco. It resembles a cartographic study composed of printed stones, currents drawn as lines, and perforations that act as pathways guiding the assembly of the atmosphere.

In Surface to Air XXXII and Surface to Air XXXVIII, we encounter two moments: being above the clouds, and ascending/descending toward a human settlement. In both, millennia-old marbles are inlaid, softening the squared grid of the frame; a space between sea, clouds, mountain ranges, and the faint suggestion of an urban grid at the periphery. Where do these marbles come from? The artist traces their journey from stone formation millions of years ago to a restoration workshop in Naples, where precious marbles gather like a treasure.

In Surface to Air XXXIV, XXXV, and XXXIII, the atmosphere grows drier. They appear as three seconds of video stills—barren earth, a Martian landscape, or the crater of a celestial body. The Tartaruga marbles reveal their cavities leading into the fresco’s interior. These openings confirm that life was once fossilized in them, fading and leaving voids behind.

The series Surface to Air owes its title to the perspective it proposes: observing the atmosphere and cloud movement from the ground upward or from the sky downward. Yet the name also evokes missiles launched from land or sea toward an aircraft or incoming projectile. Today, the global political landscape is in crisis: the rise of the far right, ongoing genocides—uninterrupted by any organization capable of intervening—ecocides, and relentless dynamics of colonial, extractivist, dominant, and erasing violence.

Symbolically, the missile is a rupture that shatters calm. What would happen if that apparent stability were suddenly disrupted by something symbolizing a missile strike? There is no need to imagine it—this is the daily reality of millions across the planet, and through our devices we have access to images of multiple coexisting realities.

In this sense, the serene temporality of cloud movement represented in the frescoes might hold only a few microseconds of contemplation—instants before or after the destabilization of a missile or the bombardment of war images accumulating in our minds.

The materiality of the frescoes intertwines with their content by revealing and contrasting temporal processes—the different rhythms matter requires to take shape. The frescoes consist of layers: the plaster surface, the embedded minerals, and within them a metallic aluminum support holding the image industrially.

Remembering Historical Frescoes

The artist’s historical relationship with painting is evident in both his interest in the medium and his references to frescoes by Piero della Francesca, Fra Angelico, and Masaccio. In Legenda Aurea Inversa (VII, fragment 1), a figure from another time appears. When we encounter it, Sala invites us—through our cellphones—to switch the camera to negative mode in order to discover, on our own devices, colors resembling those of Piero della Francesca. In Cristo Deriso (Fragment 1) the inversion from positive to negative directly recalls Fra Angelico, establishing a dialogue between digital techniques and classical painting. The reflection of natural light from the gallery collides with the fresco’s aluminum backing, creating a zigzagging halo around the piece. Finally, in The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (Inversa), inspired by Masaccio, the two figures—expressing pain and confusion beside the interior of a shell—appear as if newly revealed and seen backlit, like a negative. The faces in the fresco bear textures reminiscent of sand and earth. The fresco process becomes a metaphor for time: lime sets slowly, layer by layer, like the assembly of a video in which moving images are edited without linear narrative, oscillating between flow and rupture. Fresco and video thus share a tension between the permanence of matter and the ephemerality of the image.

Celluloid Against the Light

Our eyes are accustomed to seeing images in positive—but how do we relate to images when they are in negative? During the conversation, Sala mentioned that this translation of colors is not intuitive, making it difficult to decipher the colors painted negatively in the fresco. What reflections arise when we use our phones to view the original colors of paintings presented to us in negative? What happens when we look at a painting through a cellphone?

When visiting exhibitions, we constantly pull out our phones to document experiences or photograph images we want to remember. The choreographic act of placing the phone before the painting—and the device itself distorting the color—allows the image and our bodies to inhabit two simultaneous spaces: virtual and physical.

It is only through a technological mediator, such as a projector or cellphone, that we can see the colors in positive. The exercise of looking at a painting in negative and translating it into positive through our phones reveals an older version of the image. This action underscores the way we live in-and-outside the screen, emphasizing our dependence on technological mediation.

A Fissure to Look Closely

In fresco painting, cracks are inevitable, explained Gianmarco Biele, the artist’s assistant for this project. When I asked about the process, I understood that they result from drying and material reactions; however, I believe these fissures also want to speak. Where do these cracks lead us? How do they translate into our own time? The fissures seem almost imperceptible, yet they insist that we look closely. They ask us to gaze attentively at modernity’s failed promises, to recognize them and reorient ourselves. We stand on the edge of collapse, and it is through these fissures that we can observe, act, listen, and create meaning.

After finishing the exhibition, I stayed in the bookstore getting to know the artist’s work a bit more—page after page, book after book—moving through my body like images in motion. Staying there allowed me to situate the frescoes within a broader interweaving of his practice. When I left the gallery, I thought about the clouds and minerals in the frescoes as I walked among rocks and the sky, as if they were one and the same body. The experience gave me the chance to feel close to what has been there far longer than I have, like an interval, before returning to the chaos of life and the city.