In its second edition, the Bienal das Amazônias chooses to think of the region not as a distant territory or an exotic imaginary, but as a living system of relations, memories, and struggles. Inspired by Paraense writer Benedito Monteiro’s notion of “distance as relation,” the biennial delves into ways of understanding Amazonian art through its own ontologies and tensions, avoiding the simplifications of global environmentalism and the extractive frameworks that have historically mediated its representation. Within this context, the figure of the Acrean artist Roberto Evangelista—pioneer of Amazonian conceptualism, spiritual leader, and sharp critic of the region’s developmentalist policies—becomes a point of grounding for considering how art can activate other ecologies of knowledge. His work, which weaves together ritual, territory, and politics, continues to challenge institutional structures through a florestino ethics that recognizes the forest as both subject and teacher. In this conversation, the biennial’s co-curator Sara Garzón reflects on Evangelista’s legacy and on the curatorial challenges posed by a biennial committed to sustaining the complexity of Amazonian cosmologies without reducing them to image, resource, or metaphor. Through her perspective, a broader reflection unfolds on memory, spirituality, resistance, and the contemporary possibilities of reimagining curatorial practice from—and with—the territory

SG: While Evangelista’s work emerged during the height of global environmental movements, his approach, like that of many Latin American artists, was never aligned with environmentalism in a conventional sense. For him, there was no singular definition of “nature.” Instead, his practice articulated a “florestine/riverine consciousness,” one deeply attuned to the industrialization, extraction, and social transformations reshaping life in the Amazon throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

The political, economic, and artistic landscape of the region in the 1970s–80s clarifies how Evangelista both inherited and diverged from local traditions. Under the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964–85), the Amazon became not merely a natural territory but a laboratory for governmental vision, infrastructural expansion, and economic experimentation. The establishment of the Zona Franca de Manaus (1967) and the Polo Industrial de Manaus (ca. 1972) aimed to industrialize the region, generating a manufacturing hub driven by federal incentives. This reconfigured the socio-spatial fabric of Manaus and its surroundings: rapid urbanization, demographic growth, shifts from extractive economies to low-wage manufacturing, and the expansion of roads and new agricultural frontiers. “Nature,” as you can imagine, became a contested, mediated, and increasingly instrumentalized space.

In this context, the biennial’s task was not to translate Evangelista’s florestine consciousness into the lexicon of green environmentalism, but to let his thought unsettle the very frameworks through which “ecology,” “nature,” and “sustainability” are being institutionalized. His reflections on the “citizenship of the forest” offered a guiding principle, an entry point for conceiving this vast, layered territory as a subject in its own right, and for understanding relationality as a fundamental measure of being.

dvs: Evangelista defended the forest as a system of knowledge rather than as landscape or resource. What does it mean to curate from that perspective today, at a moment when the Amazon continues to be translated through extractive frameworks, material as well as symbolic?

SG: For Evangelista, the forest was neither a landscape to be represented nor a resource to be extracted; it was a system of knowledge, an epistemic and ethical environment. To curate from that perspective required shifting the curatorial field from representation to relation, from exhibiting the forest as an object of study to engaging it as a subject that organizes, teaches, and ultimately transforms our subjectivities.

Mater Dolorosa — In memoriam II. A criação e sobrevivência das formas (1978) was one of Evangelista’s most emblematic works. Originally conceived prior to the popularization of video art, the 26-minute film merges experimental cinema and visual art, and was broadcasted on national television. Through its narration and imagery, Evangelista meditates on creation, survival, and artistic process, presenting geometric forms like circles, squares, triangles, as symbols of continuity and resistance. These “constructivist” forms gestured towards cultural recovery amid the erasure of local lifeways.

With that in mind, rather than presenting the Amazon as an image of crisis or a site of preservation, we envisioned the biennial as a space of encounter, where the artists, forests, rivers, cities, and more-than-human entities could articulate relations in their own terms.

dvs: Evangelista’s notion of an “ecology of the spirit” proposed a convergence between art, myth, and politics. How can the biennial sustain that convergence without romanticizing it?

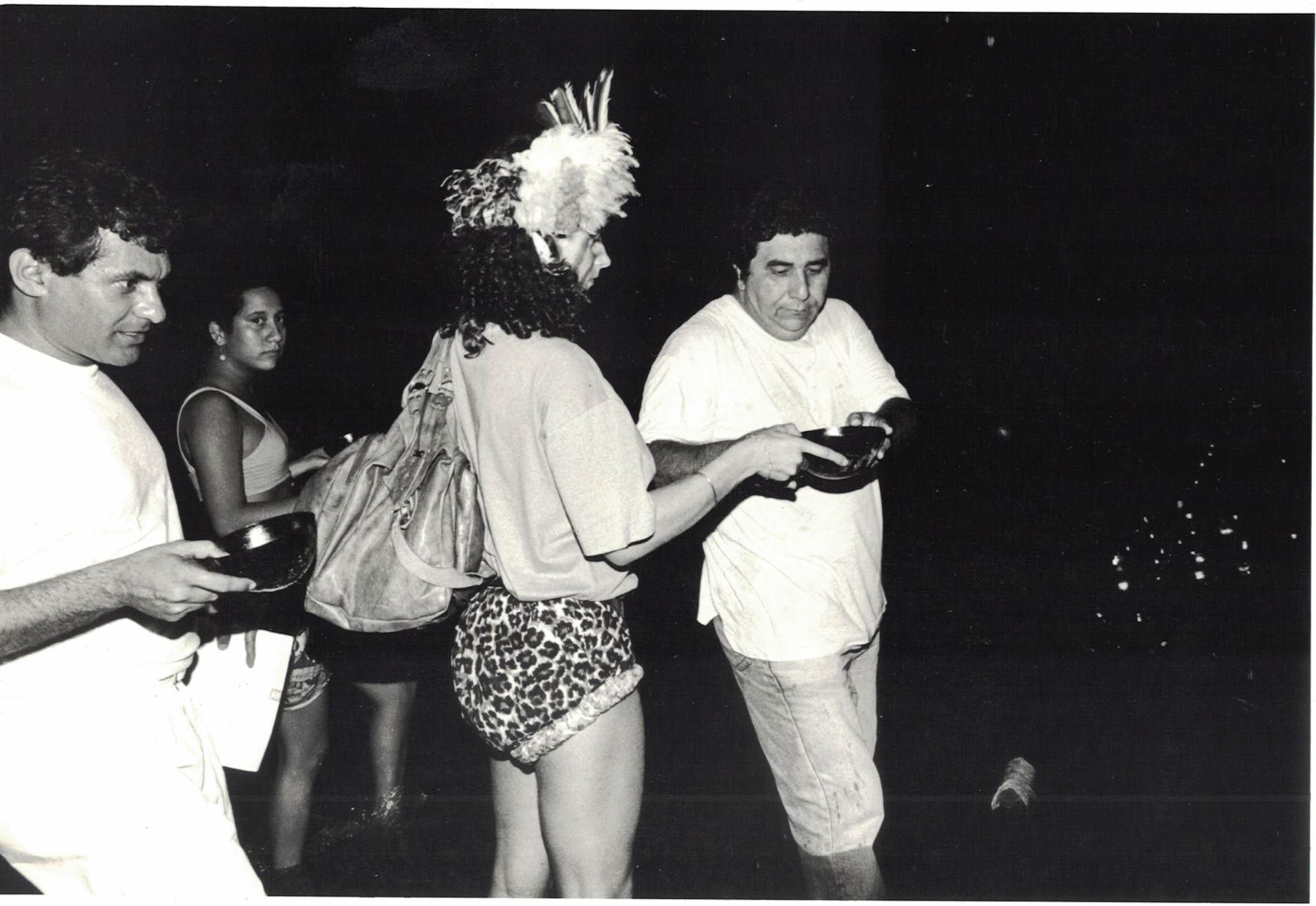

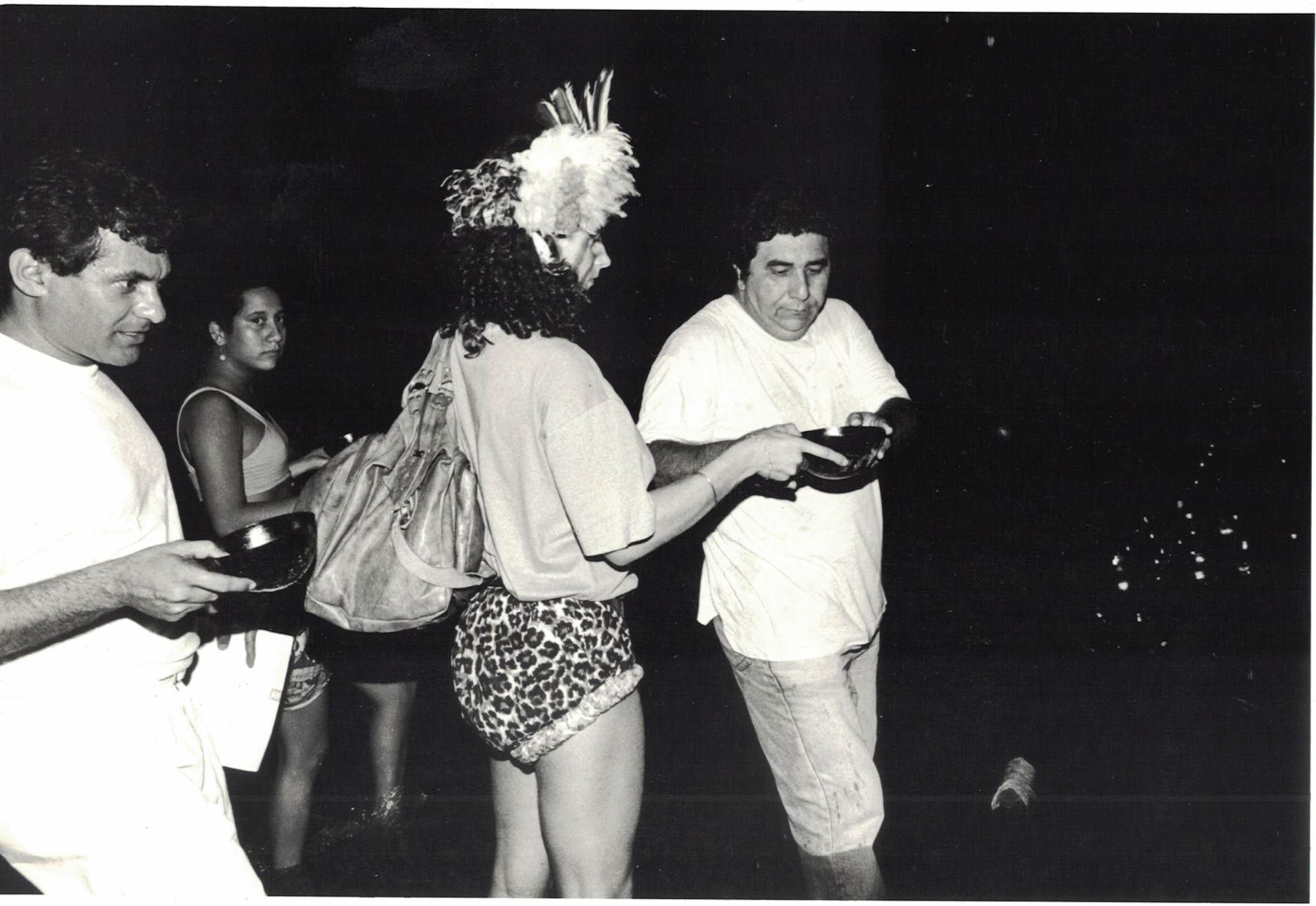

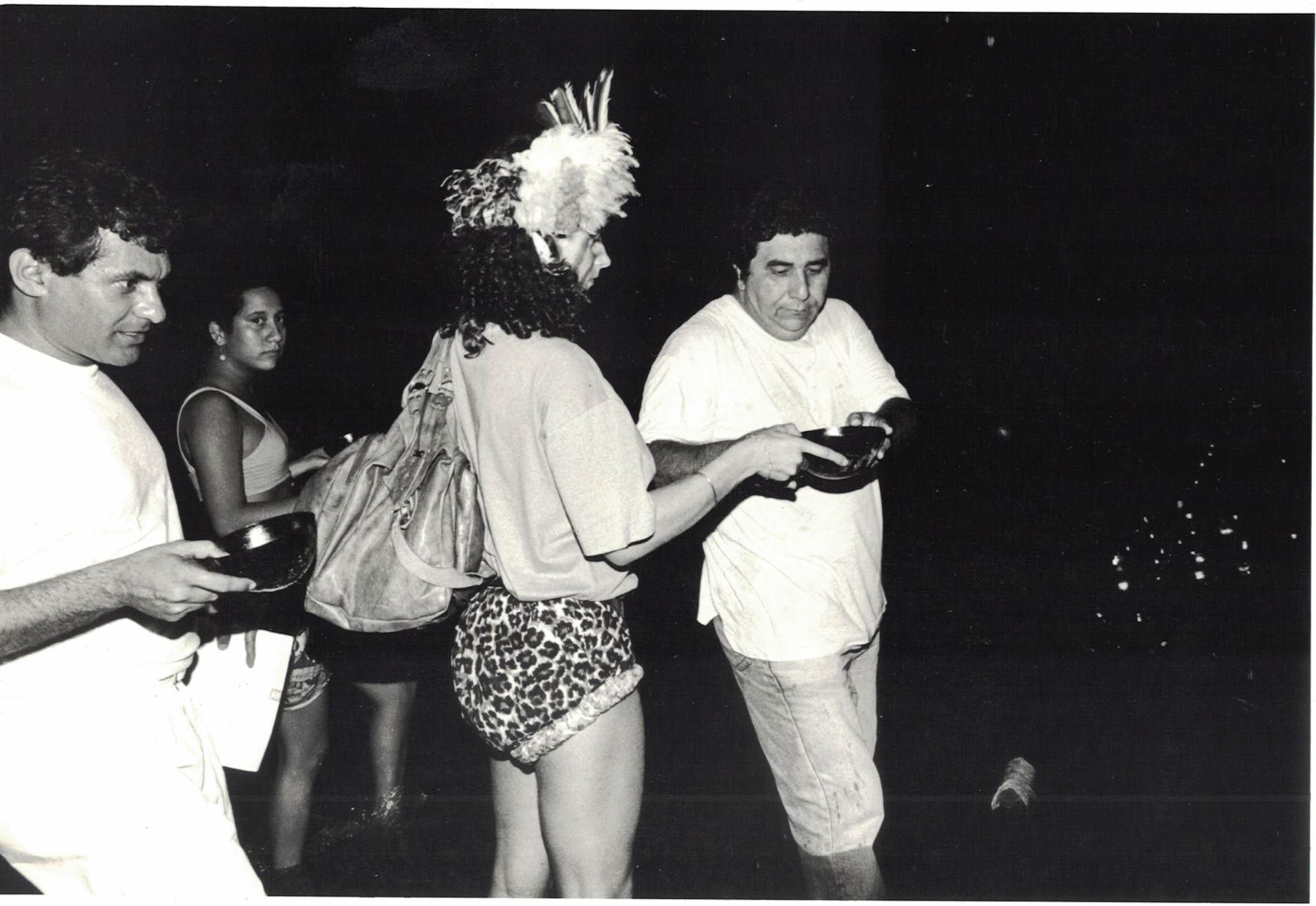

SG: Evangelista’s engagement with the forest was never limited to a metaphor. His spiritual leadership within the União do Vegetal (UDV) was characterized by a deep reverence for local traditions, emphasizing the importance of the sacred tea, Hoasca, and its role in facilitating spiritual growth. Evangelista’s contributions were, in fact, instrumental in fostering a community that balanced spiritual discipline with artistic expression.

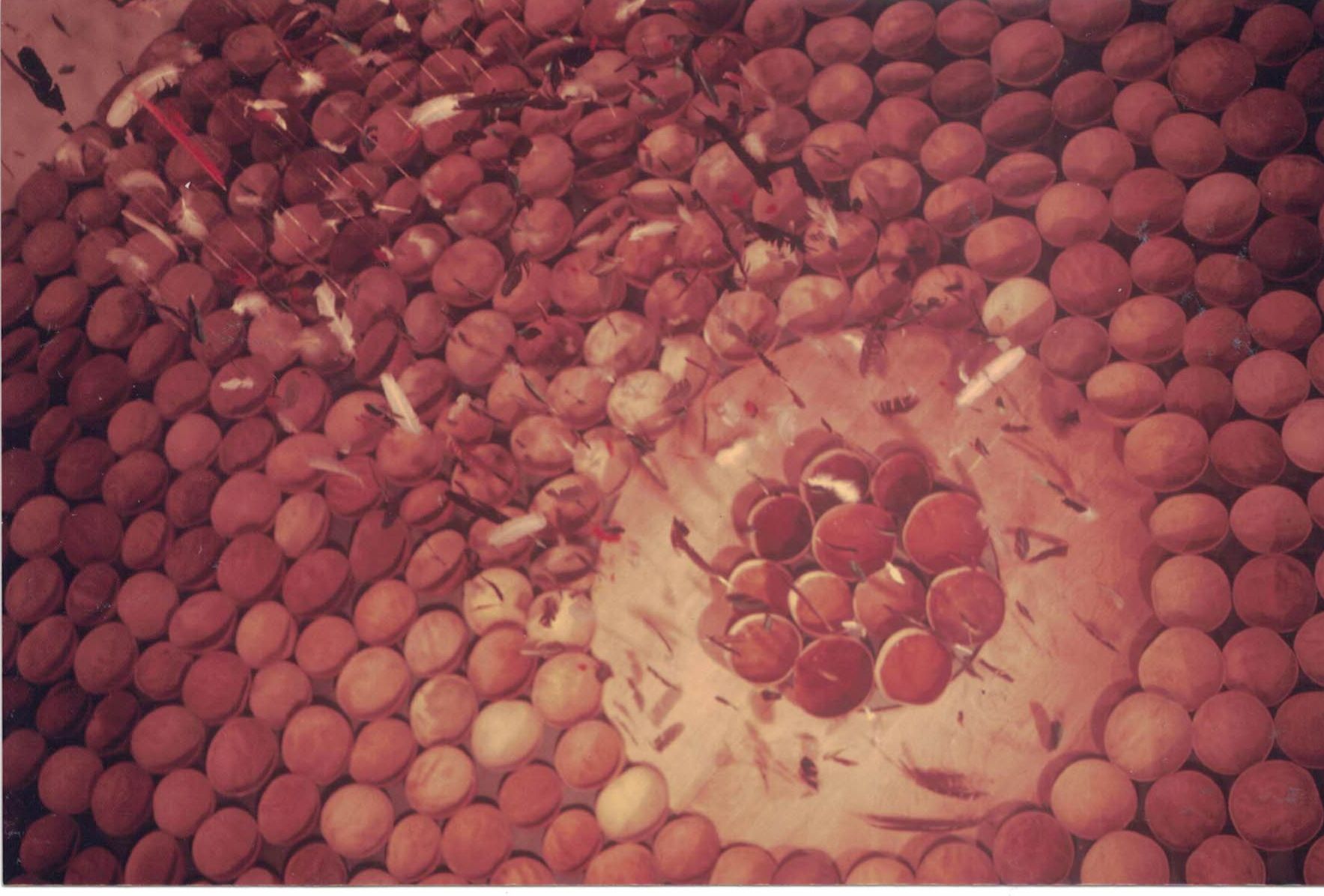

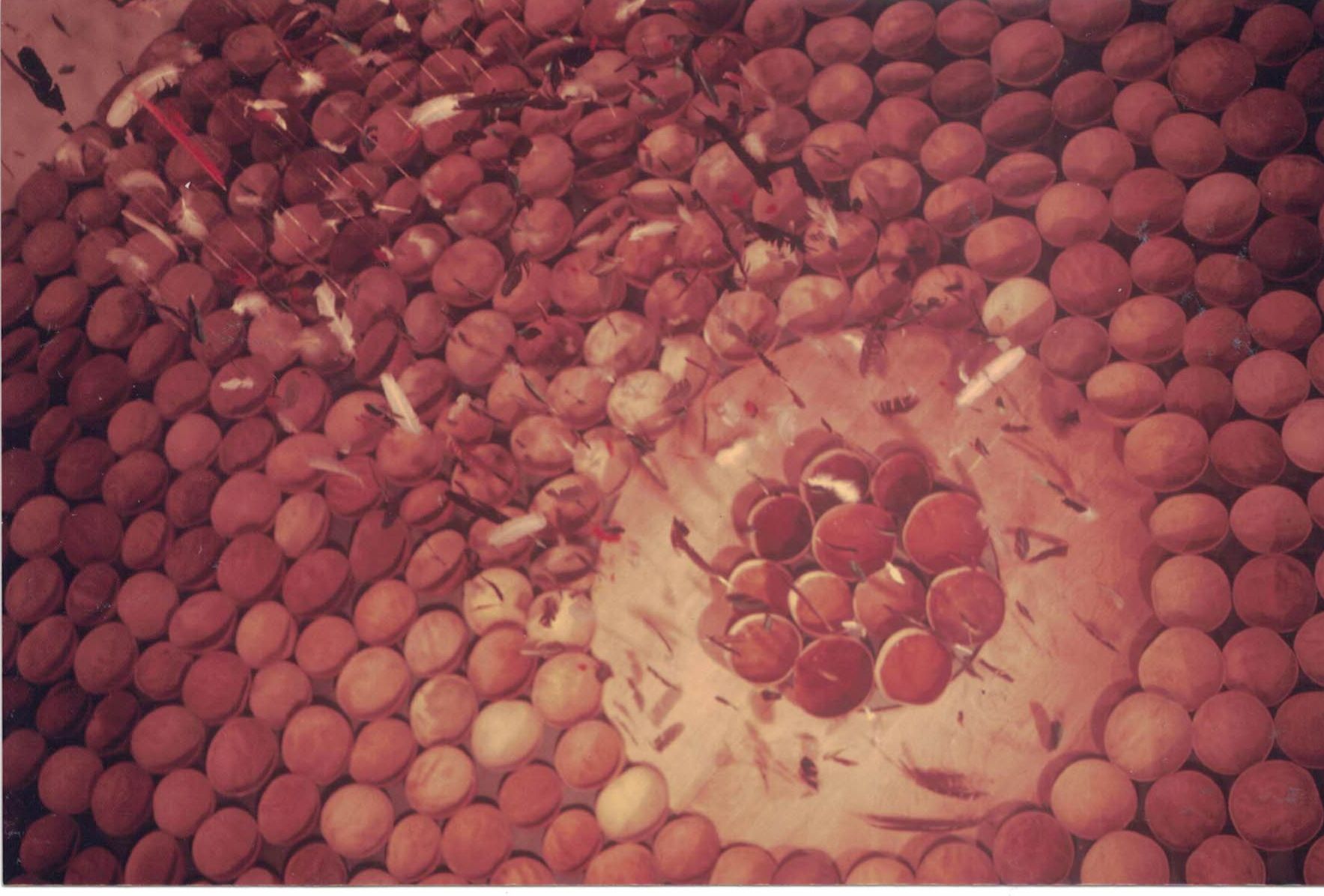

In addition to that, he was committed to the social and political realities of the Amazon. His installation Nika Uicana, conceived as an homage to Chico Mendes (1944-1988), the rubber tapper, union leader, and environmental activist assassinated in 1988, stands as evidence of how Evangelista’s florestine sensibility was a form of political consciousness. By evoking Mendes’s struggle to defend the forest and its communities against extractivist violence and political overreach, Evangelista affirmed that any “ecology of the spirit” must also account for the material conditions and human costs of environmental subjugation.

In Nika Uicana, the forest becomes not merely a site of spirituality, but a field of resistance or, put differently, a living archive of collective struggle. Evangelista’s tribute to Mendes acknowledges that the forest’s vitality depends on those who defend it, situating his art within a broader network of ecological and social activism.

SG: Evangelista remains unsettling because his practice defies institutional containment. His art was ephemeral, participatory, and site-specific, rooted in cosmological ethics rather than institutional validation. By blurring the boundaries between art and matter, concept and action, he exposes the limitations of any art institution, which seeks to present final “objects of art” as distinct from territory, political action, or even spiritual practice. To think with Evangelista is to privilege relationality over representation, allowing us to turn the biennial into a space of co-creation, one less concerned with displaying mythic symbolism and instead more attentive to the politics of relation.

SG: While Evangelista’s work emerged during the height of global environmental movements, his approach, like that of many Latin American artists, was never aligned with environmentalism in a conventional sense. For him, there was no singular definition of “nature.” Instead, his practice articulated a “florestine/riverine consciousness,” one deeply attuned to the industrialization, extraction, and social transformations reshaping life in the Amazon throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

The political, economic, and artistic landscape of the region in the 1970s–80s clarifies how Evangelista both inherited and diverged from local traditions. Under the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964–85), the Amazon became not merely a natural territory but a laboratory for governmental vision, infrastructural expansion, and economic experimentation. The establishment of the Zona Franca de Manaus (1967) and the Polo Industrial de Manaus (ca. 1972) aimed to industrialize the region, generating a manufacturing hub driven by federal incentives. This reconfigured the socio-spatial fabric of Manaus and its surroundings: rapid urbanization, demographic growth, shifts from extractive economies to low-wage manufacturing, and the expansion of roads and new agricultural frontiers. “Nature,” as you can imagine, became a contested, mediated, and increasingly instrumentalized space.

In this context, the biennial’s task was not to translate Evangelista’s florestine consciousness into the lexicon of green environmentalism, but to let his thought unsettle the very frameworks through which “ecology,” “nature,” and “sustainability” are being institutionalized. His reflections on the “citizenship of the forest” offered a guiding principle, an entry point for conceiving this vast, layered territory as a subject in its own right, and for understanding relationality as a fundamental measure of being.

dvs: Evangelista defended the forest as a system of knowledge rather than as landscape or resource. What does it mean to curate from that perspective today, at a moment when the Amazon continues to be translated through extractive frameworks, material as well as symbolic?

SG: For Evangelista, the forest was neither a landscape to be represented nor a resource to be extracted; it was a system of knowledge, an epistemic and ethical environment. To curate from that perspective required shifting the curatorial field from representation to relation, from exhibiting the forest as an object of study to engaging it as a subject that organizes, teaches, and ultimately transforms our subjectivities.

Mater Dolorosa — In memoriam II. A criação e sobrevivência das formas (1978) was one of Evangelista’s most emblematic works. Originally conceived prior to the popularization of video art, the 26-minute film merges experimental cinema and visual art, and was broadcasted on national television. Through its narration and imagery, Evangelista meditates on creation, survival, and artistic process, presenting geometric forms like circles, squares, triangles, as symbols of continuity and resistance. These “constructivist” forms gestured towards cultural recovery amid the erasure of local lifeways.

With that in mind, rather than presenting the Amazon as an image of crisis or a site of preservation, we envisioned the biennial as a space of encounter, where the artists, forests, rivers, cities, and more-than-human entities could articulate relations in their own terms.

dvs: Evangelista’s notion of an “ecology of the spirit” proposed a convergence between art, myth, and politics. How can the biennial sustain that convergence without romanticizing it?

SG: Evangelista’s engagement with the forest was never limited to a metaphor. His spiritual leadership within the União do Vegetal (UDV) was characterized by a deep reverence for local traditions, emphasizing the importance of the sacred tea, Hoasca, and its role in facilitating spiritual growth. Evangelista’s contributions were, in fact, instrumental in fostering a community that balanced spiritual discipline with artistic expression.

In addition to that, he was committed to the social and political realities of the Amazon. His installation Nika Uicana, conceived as an homage to Chico Mendes (1944-1988), the rubber tapper, union leader, and environmental activist assassinated in 1988, stands as evidence of how Evangelista’s florestine sensibility was a form of political consciousness. By evoking Mendes’s struggle to defend the forest and its communities against extractivist violence and political overreach, Evangelista affirmed that any “ecology of the spirit” must also account for the material conditions and human costs of environmental subjugation.

In Nika Uicana, the forest becomes not merely a site of spirituality, but a field of resistance or, put differently, a living archive of collective struggle. Evangelista’s tribute to Mendes acknowledges that the forest’s vitality depends on those who defend it, situating his art within a broader network of ecological and social activism.

SG: Evangelista remains unsettling because his practice defies institutional containment. His art was ephemeral, participatory, and site-specific, rooted in cosmological ethics rather than institutional validation. By blurring the boundaries between art and matter, concept and action, he exposes the limitations of any art institution, which seeks to present final “objects of art” as distinct from territory, political action, or even spiritual practice. To think with Evangelista is to privilege relationality over representation, allowing us to turn the biennial into a space of co-creation, one less concerned with displaying mythic symbolism and instead more attentive to the politics of relation.