“Estalo,” a snap, a flash, an almost immediate moment. Within the publication of readings accompanying the 14th Mercosur Biennial, Dr. Andrea M. Gómez articulates a reflection on plasticity—neuronal, genetic, and symbolic—as a vital force that balances order and chaos. Through a writing style that moves between scientific discourse and mythopoetic imagination, the author examines the biological mechanisms of change—from RNA alternative splicing to synaptic plasticity—as metaphors for thought, perception, and interspecies communication. The essay proposes a psychedelic and ecological reading of knowledge, where molecular biology becomes a shared language among humans, fungi, animals, and trickster gods (such as Coyote)

Plasticity is the tendency for life to transform without breaking or collapsing into meaningless chaos. Of course, this tendency also exists in our brain, which is made of interconnected, interdependent, but individual units (e.g., neurons) that process external information indirectly from within the black box of our cranium. Or rather, it makes the best attempt to make sense of external information so long as the brain’s perceptions, associations, and predictions increase our chance for survival. This tendency for the brain to change itself, whether it changes its structure or function, is known as neural plasticity. Whether it changes the connections or synapses is known as "synaptic plasticity". In all cases, again, plasticity in an ideal scenario should work to ensure our survival. However, the brain’s ability to change itself presents a paradox: if plasticity were too excessive, our memories would vanish; on the other hand, if plasticity were too rigid, we would not be able to learn. With this perspective, we can appreciate neural plasticity as neither good nor bad but a law of nature that balances order and chaos. Then what biological entity, or otherwise, keeps this balance between order and chaos in check? How can we begin to make sense of this balance when it is challenged by either the mundane or by profound mind-altering shifts in perception and self-such as what occurs with psychedelics?

Dogma vs splicing

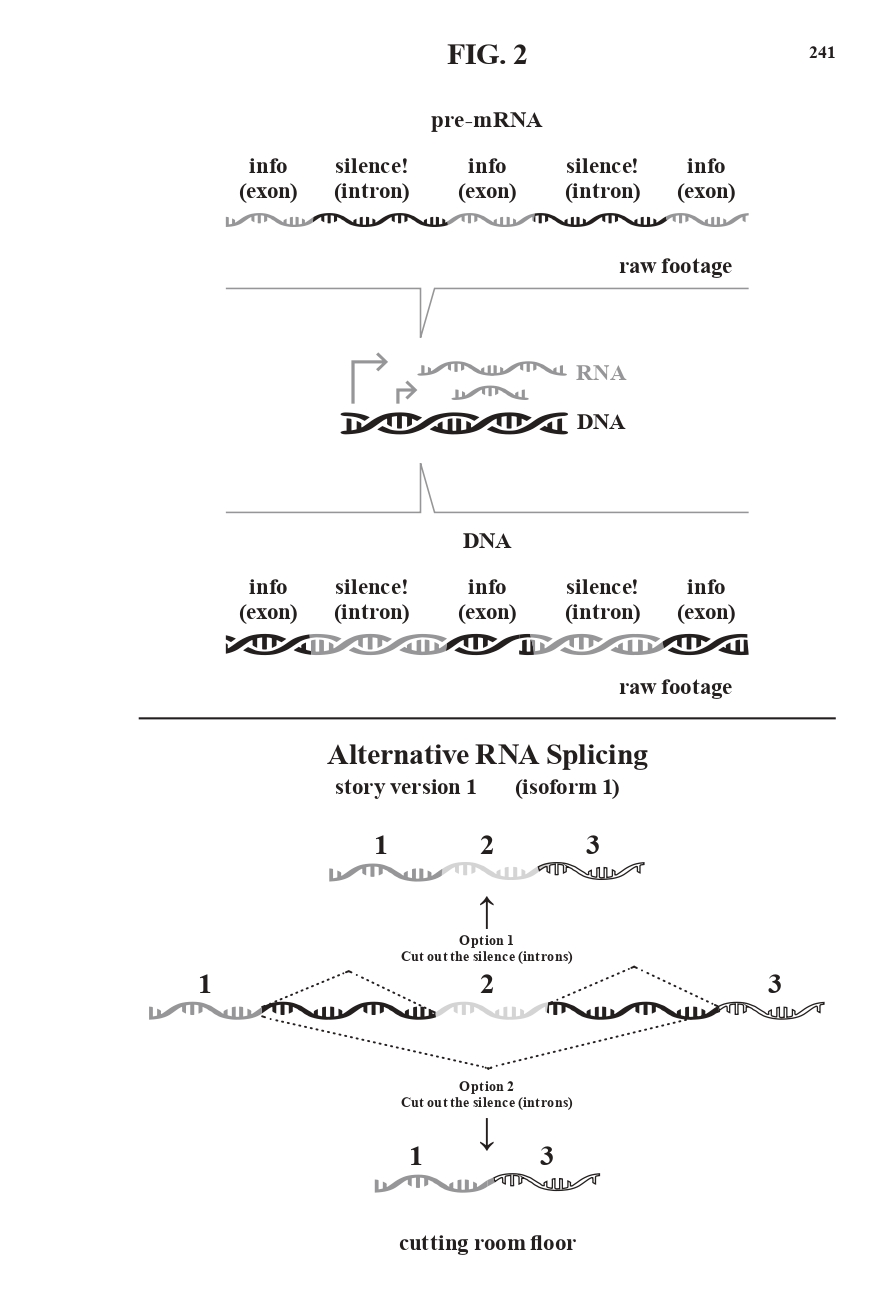

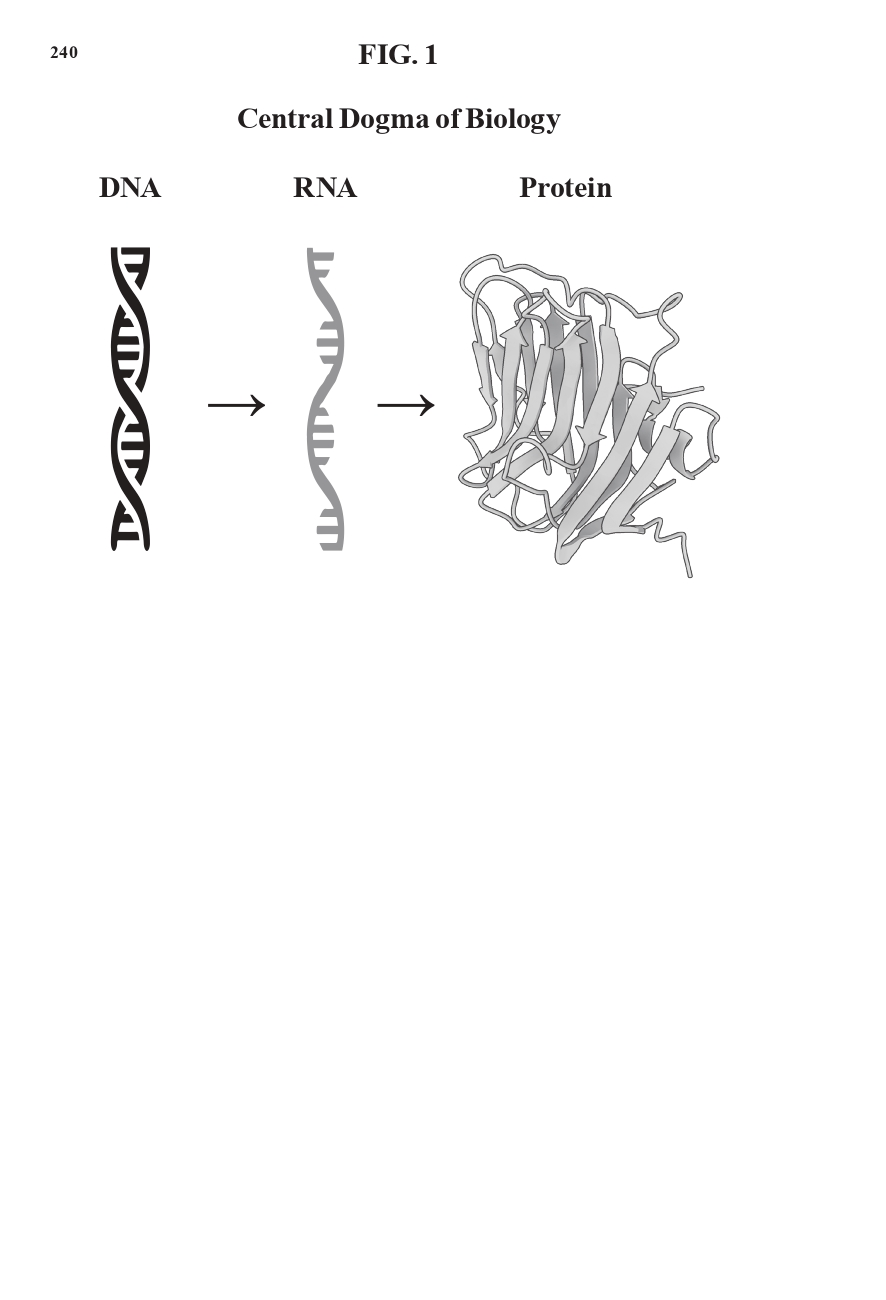

Should you ask this question to a biologist (or any “-ologist” mired in professional perspective), they would enthusiastically point you to dogma. So, let’s examine a favorite dogma of biologists: the central dogma (FIG. 1) . Simply put, the central dogma describes in biochemical terms - the direction from which life flows. From its storage at the DNA level to its retrieval at the RNA level, life’s information, now untangled, crystallizes at the protein level, where its products carry out the daily operations of life. Emanating from the DNA, all life flows. However, like all dogmas, the central dogma also struggles to maintain relevance. How is flexibility maintained along this linear track? What about stability? Further, adding insult to injury, when we compare our genetic code to chimps, we are nearly identical to our distant cousins (96%). When comparing a human to another human, we are 99.9% identical. Since the components are nearly identical, how can their action lead to individual differences in perception – from primate to primate, or from human to human? nsight into these conundrums revealed themselves upon a closer look at the genetic code. The DNA sequence that eventually becomes protein (exons) was not continuous. Instead, exons were interrupted by bouts of silence.

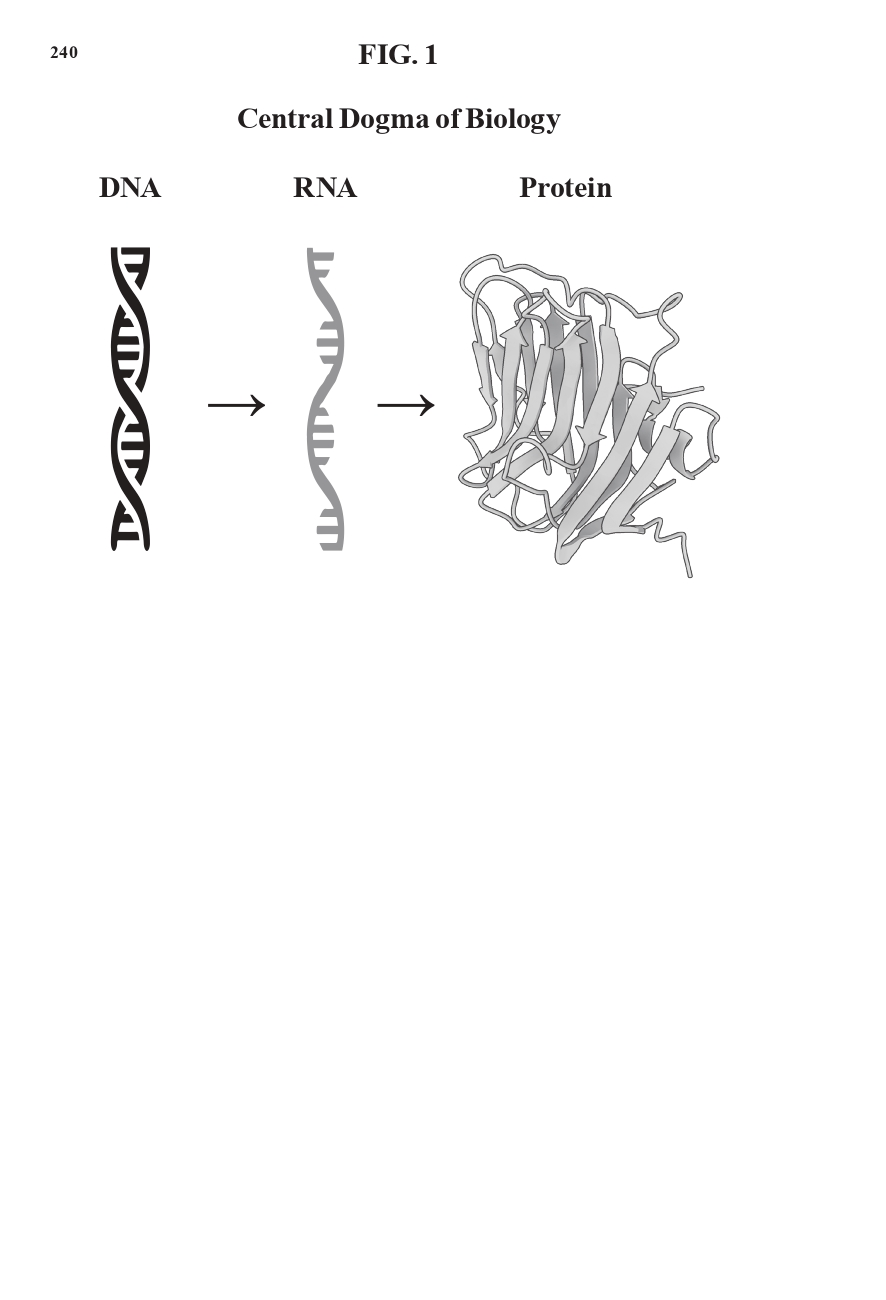

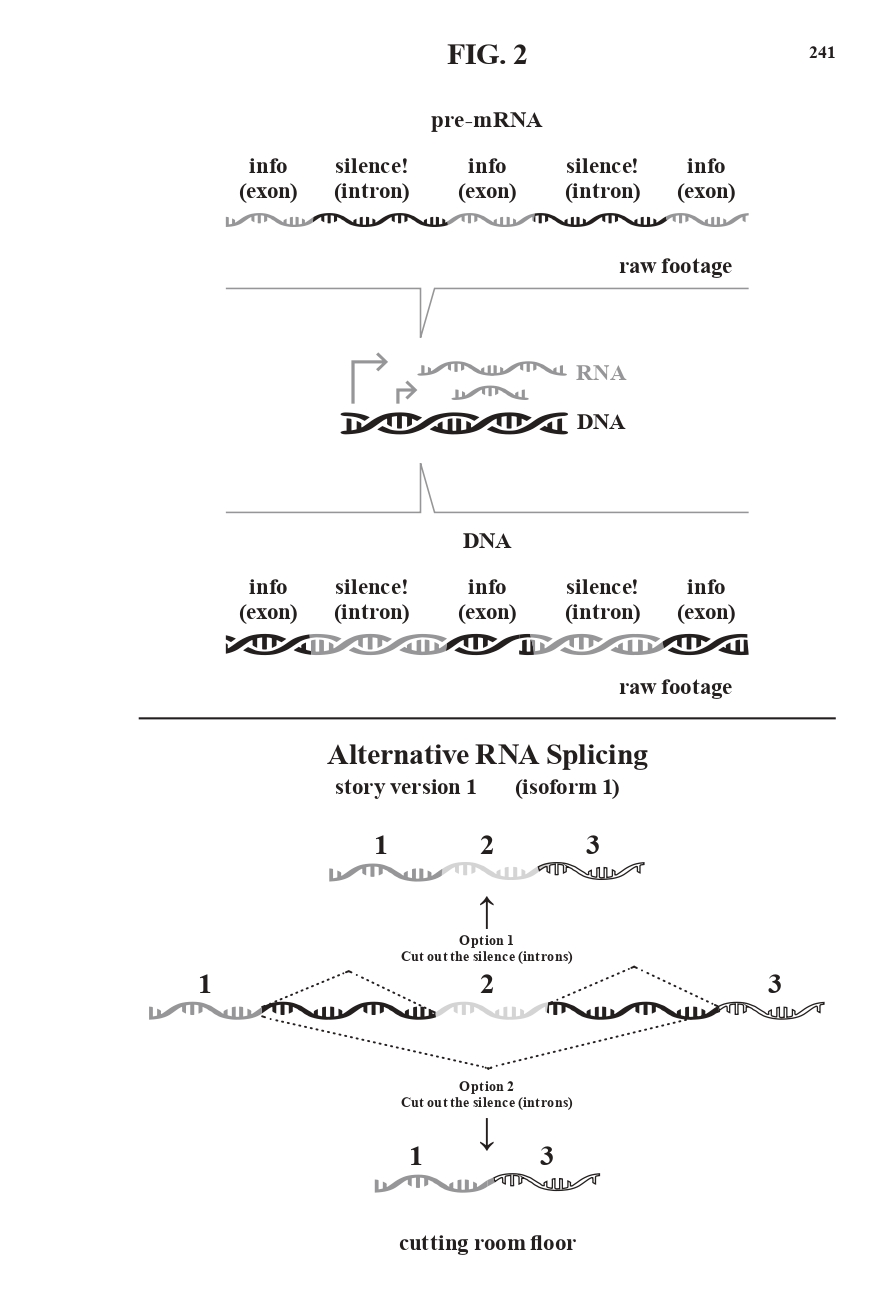

These silent or non-coding regions are called introns (intragenic regions). However, transcribing the DNA to na RNA product yields a product that still contains the introns. How does one deal with these rude interrupters? Cut them out! Like editing a movie, the raw footage containing the silent introns are enzymatically chopped out. As the introns drop quietly to the editing room floor, the exons are spliced together, and information can now proceed uninterrupted to become proteins. It’s here that the story of us gets more exciting. Like a filmmaker deciding which scenes to cut and which to keep, potentially creating different versions of the story, alternate combinations of RNA can be spliced together - termed alternative RNA splicing (FIG. 2). With this simple cut-and-pasting mechanism, we now have a strategy to explain differences between us and our primate relatives and between us and our human relatives, as well as an explanation for how the flow of genetic information can remain stable and flexible simultaneously. Stable at the DNA level. Flexible at the RNA level.

Shall we pause with the metaphors, such as editing room floors, to explain how complexity and diversity are generated during evolution and revisit synaptic plasticity? A materialistic view is necessary to understand an empirical version of the lived, somatic and cognitive experience of perception. We will start with sensory transduction, as it is the first step in perception. Physical stimuli, whether an odor, a taste, a photon, a change in pressure, or an indentation in the skin, are detected by specialized sensory neurons throughout our body, transforming odors, photons, and pressures into neural activity. As the electrical impulse propagates from the periphery to the brain, the propagation of that activity is not continuous. It is interrupted as activity passes from neuron to neuron throughout the brain. The site of these interruptions are synapses.

At their core, synapses are tiny communication devices. However, instead of communicating via a continuous flow of electrical current, they signal with chemicals. A signaling molecule and its receptor are required for communication between neurons. Triggered by an electrical impulse, a chemical signal called a "neurotransmitter" is released from the inside of the neuron to the outside, where it may float away. However, suppose the neurotransmitter is close enough to a receptor on an adjacent neuron. In that case, it will bind, change the receptor’s shape, and initiate a tiny flux of ionic current. Suppose enough 243 neurotransmitters are released and bind to a sufficient number of receptors. In that case, the rush of current flowing into the neuron is sufficient to trigger an impulse that propagates throughout the cell and onto the rest of the circuit.

When compared to an electrical transmission, a chemical transmission is much slower. The accumulation of interruptions distributed throughout the neural network determines whether select neuron ensembles are recruited to a sensory percept. One way to recruit select ensembles of neurons to a percept is by changing the strength of synaptic transmission. Increase the number of neurotransmitters released or decrease the number of neurotransmitters released. Increase the number of neurotransmitter receptors or decrease the number of neurotransmitter receptors. Changes to the magnitude of synaptic transmission is synaptic plasticity. As a reminder, the directionality of change – synapses weakening or synapses strengthening – is neither good nor bad. The directionality is simply the working space that alters the identity of neural ensembles recruited to percepts. Again, ideally, creating meaningful internal representations of the external world that contribute to our survival.

With so many sources of external input, how does the brain decide which ensembles are the most important at any given moment? Here is where neuromodulators play a role. Oxytocin, serotonin, dopamine, acetylcholine, and noradrenaline are all neuromodulators that serve to bias which ensembles of neurons are the most important but typically operate to recruit ensembles of neurons on a short time scale. The synthesis of neuromodulators happens internally. Amino acids consumed by us via diet get converted by enzymatic pathways to the various neuromodulators needed for cellular communication. Of course, we are not the only species that synthesize neuromod— An interruption in transmission occurs. Coyote steps into frame and taps the mic.

“And we’re live! Welcome back, beautiful people, to this incredible finale. Coyote here, reporting live at the finish line of what can only be described as 100% unadulterated inspiration. Folks, get ready to be swept away by the finale of the race to discover psychedelics.”

“As you see, dear viewers, the crowd is going wild. They’re excited. I’m excited. I hope you can also feel the excitement at home, folks.” Coyote trots over to the winner’s circle, where the champions, Mushroom, Toad, and Cactus, are basking in their well deserved glory.

“Before we celebrate our winners, let’s check back in with the last racer, Western Science, who is now coming in from the horizon, entering the final stretch of the race.” Coyote continues,” His resilience is a testament that this race isn’t just about winning. It’s about grit. It’s about determination. And it’s about the focus to make it to the end.”

“Now, we have Mushroom here, discoverer of psychedelic tryptamines and ergolines.” Coyote lifting the mic to Mushroom. “Mushroom, what do you think of Western Science?” Mushroom, in their characteristic mycelial tone, replies. “I am truly inspired by Western Science’s innovative spirit.” Mushroom pauses for an uncomfortable amount of time. “Yes. They truly embody the essence of this race. Afterall, they invented the study of Chemistry to mimic what took me ages to evolve.” Teary-eyed, Coyote concludes,

“Wow. Truly an inspiration. Back to you,

Andrea.”

Of course, we are not the only species that synthesize neuromodulators. The enzymatic pathways we use to synthesize neuromodulators that serve as the currency for our neurotransmission exist across all of life. Some species have evolved to use the same pathways as us. Other species use similar pathways, but that slightly deviate from ours. Let’s take the amino acid tryptophan, for example. We and other animals ingest tryptophan, and we use it to synthesize serotonin. Similarly, the group of closely related Psilocybe mushrooms uses tryptophan, but instead of producing serotonin, their enzymatic pathways produce the psychedelic psilocybin. Why? Interestingly, not all members of Psilocybe synthesize psilocybin. However, those that do, live in ecosystems close with other animals. Do they produce psilocybin from tryptophan similar in function to why we use it? We use it to change the timing of synaptic interruption, ensemble recruitment, and to alter synaptic plasticity. Why would mushrooms use it? Maybe they use it to communicat with us. What are they trying to say?

Psychedelics produced by animals, plants, or fungi profoundly alter the way we perceive external input. Given its structural similarity to serotonin, psychedelics can bind to our serotonin receptors, thus changing the timing of synaptic transmission and changing the identities of neuronal ensembles that are recruited to our percepts. Given the profound magnitude of changes to reality and perception during psychedelic exposure, how is it that we do not delve into complete chaos? Put in another way; we know very little about the mechanisms that enable neural plasticity for learning while stably retaining existing memories throughout a lifetime. Empirical evidence collected from the scientists in my lab demonstrates that a single psychedelic dose robustly and persistently alters alternative splicing lasting at least a month with hardly any changes in how DNA is transcribed. Back to our filmmaking metaphor, the raw footage did not change. Instead, shifts in perception induced by psychedelic exposure created different versions of the same story.

Plasticity is the tendency for life to transform without breaking or collapsing into meaningless chaos. Of course, this tendency also exists in our brain, which is made of interconnected, interdependent, but individual units (e.g., neurons) that process external information indirectly from within the black box of our cranium. Or rather, it makes the best attempt to make sense of external information so long as the brain’s perceptions, associations, and predictions increase our chance for survival. This tendency for the brain to change itself, whether it changes its structure or function, is known as neural plasticity. Whether it changes the connections or synapses is known as "synaptic plasticity". In all cases, again, plasticity in an ideal scenario should work to ensure our survival. However, the brain’s ability to change itself presents a paradox: if plasticity were too excessive, our memories would vanish; on the other hand, if plasticity were too rigid, we would not be able to learn. With this perspective, we can appreciate neural plasticity as neither good nor bad but a law of nature that balances order and chaos. Then what biological entity, or otherwise, keeps this balance between order and chaos in check? How can we begin to make sense of this balance when it is challenged by either the mundane or by profound mind-altering shifts in perception and self-such as what occurs with psychedelics?

Dogma vs splicing

Should you ask this question to a biologist (or any “-ologist” mired in professional perspective), they would enthusiastically point you to dogma. So, let’s examine a favorite dogma of biologists: the central dogma (FIG. 1) . Simply put, the central dogma describes in biochemical terms - the direction from which life flows. From its storage at the DNA level to its retrieval at the RNA level, life’s information, now untangled, crystallizes at the protein level, where its products carry out the daily operations of life. Emanating from the DNA, all life flows. However, like all dogmas, the central dogma also struggles to maintain relevance. How is flexibility maintained along this linear track? What about stability? Further, adding insult to injury, when we compare our genetic code to chimps, we are nearly identical to our distant cousins (96%). When comparing a human to another human, we are 99.9% identical. Since the components are nearly identical, how can their action lead to individual differences in perception – from primate to primate, or from human to human? nsight into these conundrums revealed themselves upon a closer look at the genetic code. The DNA sequence that eventually becomes protein (exons) was not continuous. Instead, exons were interrupted by bouts of silence.

These silent or non-coding regions are called introns (intragenic regions). However, transcribing the DNA to na RNA product yields a product that still contains the introns. How does one deal with these rude interrupters? Cut them out! Like editing a movie, the raw footage containing the silent introns are enzymatically chopped out. As the introns drop quietly to the editing room floor, the exons are spliced together, and information can now proceed uninterrupted to become proteins. It’s here that the story of us gets more exciting. Like a filmmaker deciding which scenes to cut and which to keep, potentially creating different versions of the story, alternate combinations of RNA can be spliced together - termed alternative RNA splicing (FIG. 2). With this simple cut-and-pasting mechanism, we now have a strategy to explain differences between us and our primate relatives and between us and our human relatives, as well as an explanation for how the flow of genetic information can remain stable and flexible simultaneously. Stable at the DNA level. Flexible at the RNA level.

Shall we pause with the metaphors, such as editing room floors, to explain how complexity and diversity are generated during evolution and revisit synaptic plasticity? A materialistic view is necessary to understand an empirical version of the lived, somatic and cognitive experience of perception. We will start with sensory transduction, as it is the first step in perception. Physical stimuli, whether an odor, a taste, a photon, a change in pressure, or an indentation in the skin, are detected by specialized sensory neurons throughout our body, transforming odors, photons, and pressures into neural activity. As the electrical impulse propagates from the periphery to the brain, the propagation of that activity is not continuous. It is interrupted as activity passes from neuron to neuron throughout the brain. The site of these interruptions are synapses.

At their core, synapses are tiny communication devices. However, instead of communicating via a continuous flow of electrical current, they signal with chemicals. A signaling molecule and its receptor are required for communication between neurons. Triggered by an electrical impulse, a chemical signal called a "neurotransmitter" is released from the inside of the neuron to the outside, where it may float away. However, suppose the neurotransmitter is close enough to a receptor on an adjacent neuron. In that case, it will bind, change the receptor’s shape, and initiate a tiny flux of ionic current. Suppose enough 243 neurotransmitters are released and bind to a sufficient number of receptors. In that case, the rush of current flowing into the neuron is sufficient to trigger an impulse that propagates throughout the cell and onto the rest of the circuit.

When compared to an electrical transmission, a chemical transmission is much slower. The accumulation of interruptions distributed throughout the neural network determines whether select neuron ensembles are recruited to a sensory percept. One way to recruit select ensembles of neurons to a percept is by changing the strength of synaptic transmission. Increase the number of neurotransmitters released or decrease the number of neurotransmitters released. Increase the number of neurotransmitter receptors or decrease the number of neurotransmitter receptors. Changes to the magnitude of synaptic transmission is synaptic plasticity. As a reminder, the directionality of change – synapses weakening or synapses strengthening – is neither good nor bad. The directionality is simply the working space that alters the identity of neural ensembles recruited to percepts. Again, ideally, creating meaningful internal representations of the external world that contribute to our survival.

With so many sources of external input, how does the brain decide which ensembles are the most important at any given moment? Here is where neuromodulators play a role. Oxytocin, serotonin, dopamine, acetylcholine, and noradrenaline are all neuromodulators that serve to bias which ensembles of neurons are the most important but typically operate to recruit ensembles of neurons on a short time scale. The synthesis of neuromodulators happens internally. Amino acids consumed by us via diet get converted by enzymatic pathways to the various neuromodulators needed for cellular communication. Of course, we are not the only species that synthesize neuromod— An interruption in transmission occurs. Coyote steps into frame and taps the mic.

“And we’re live! Welcome back, beautiful people, to this incredible finale. Coyote here, reporting live at the finish line of what can only be described as 100% unadulterated inspiration. Folks, get ready to be swept away by the finale of the race to discover psychedelics.”

“As you see, dear viewers, the crowd is going wild. They’re excited. I’m excited. I hope you can also feel the excitement at home, folks.” Coyote trots over to the winner’s circle, where the champions, Mushroom, Toad, and Cactus, are basking in their well deserved glory.

“Before we celebrate our winners, let’s check back in with the last racer, Western Science, who is now coming in from the horizon, entering the final stretch of the race.” Coyote continues,” His resilience is a testament that this race isn’t just about winning. It’s about grit. It’s about determination. And it’s about the focus to make it to the end.”

“Now, we have Mushroom here, discoverer of psychedelic tryptamines and ergolines.” Coyote lifting the mic to Mushroom. “Mushroom, what do you think of Western Science?” Mushroom, in their characteristic mycelial tone, replies. “I am truly inspired by Western Science’s innovative spirit.” Mushroom pauses for an uncomfortable amount of time. “Yes. They truly embody the essence of this race. Afterall, they invented the study of Chemistry to mimic what took me ages to evolve.” Teary-eyed, Coyote concludes,

“Wow. Truly an inspiration. Back to you,

Andrea.”

Of course, we are not the only species that synthesize neuromodulators. The enzymatic pathways we use to synthesize neuromodulators that serve as the currency for our neurotransmission exist across all of life. Some species have evolved to use the same pathways as us. Other species use similar pathways, but that slightly deviate from ours. Let’s take the amino acid tryptophan, for example. We and other animals ingest tryptophan, and we use it to synthesize serotonin. Similarly, the group of closely related Psilocybe mushrooms uses tryptophan, but instead of producing serotonin, their enzymatic pathways produce the psychedelic psilocybin. Why? Interestingly, not all members of Psilocybe synthesize psilocybin. However, those that do, live in ecosystems close with other animals. Do they produce psilocybin from tryptophan similar in function to why we use it? We use it to change the timing of synaptic interruption, ensemble recruitment, and to alter synaptic plasticity. Why would mushrooms use it? Maybe they use it to communicat with us. What are they trying to say?

Psychedelics produced by animals, plants, or fungi profoundly alter the way we perceive external input. Given its structural similarity to serotonin, psychedelics can bind to our serotonin receptors, thus changing the timing of synaptic transmission and changing the identities of neuronal ensembles that are recruited to our percepts. Given the profound magnitude of changes to reality and perception during psychedelic exposure, how is it that we do not delve into complete chaos? Put in another way; we know very little about the mechanisms that enable neural plasticity for learning while stably retaining existing memories throughout a lifetime. Empirical evidence collected from the scientists in my lab demonstrates that a single psychedelic dose robustly and persistently alters alternative splicing lasting at least a month with hardly any changes in how DNA is transcribed. Back to our filmmaking metaphor, the raw footage did not change. Instead, shifts in perception induced by psychedelic exposure created different versions of the same story.