Between territorial borders, violence, and democracy, Regina José Galindo presents “Democratic Spring” at Portas Vilaseca Gallery in Rio de Janeiro Curated by Daniela Labra, Galindo shares a selection of her performance work from the past seven years. “Her actions are often described as radical; yet, given the issues she addresses in her research, how could one not be radical when confronting the legacy of colonial violence in the Americas?”, writes our contributor Janaú.

Although the borders between countries are limits imposed by human invention, there is something that connects us as "Latin Americans", a term that in itself highlights the impact and legacy of colonialism in our territories. Beyond this colonial fiction, there are multiple confluences between the countries of so-called Latin America, territories that Regina Jose Galindo has researched and explored through her artistic practice, composed mostly of performances. Born in 1974 in Guatemala City, where she lives and works, Galindo is one of the most internationally recognized artists in the field of performance art. She has received important accolades, such as the Golden Lion at the 51st Venice Biennale in 2005.

Her artistic production stretches that which unites us while exposing still-open social wounds, using themes such as politics, gender, and democratic setbacks as fundamental axes of her research. Her work is part of important collections around the world and she has participated in prominent international exhibitions such as the São Paulo, Prague and Istanbul biennials, as well as institutions such as the Tate Modern (London), the Centre Pompidou (Paris) and the Guggenheim (New York), among others. With a career spanning more than two decades, her work not only denounces but also calls for change.

In Primavera Democratica, presented at Portas Vilaseca in Rio de Janeiro as part of the gallery's 15th anniversary commemorative calendar, Regina Jose Galindo brings together a series of works created from 2017 to the present. This is the first time the Brazilian city has hosted a solo exhibition by the artist. For the occasion, Galindo conceived and carried out an unprecedented on-site performance entitled Primavera Democratica [Democratic Spring], which also gives its name to the exhibition. In addition to the performance at Praça da Harmonia in downtown Rio, the gallery organized a public conversation between Galindo and Guatemalan artist Jorge de Leon, in which they shared with the public aspects of their respective careers, marked by significant performances in contemporary art.

Curated by Daniela Labra, the exhibition occupies two floors of the gallery. At the entrance, the visitor encounters a photographic record of Primavera Democratica. The performance is also documented on video, where Regina is seen lying naked on the ground while two gravediggers place wildflowers around her body. For a few minutes, the flowers form a sort of tapestry or deathbed, with the artist motionless and with her eyes closed at the center. People passing through the space stop to observe, evoking the sensation of being at a wake. However, one can also think: What does a body like that dream about? What possibilities of existence does a woman have?

The title of the work, as well as the exhibition, was conceived specifically for the Brazilian context, considering the discussions surrounding the limits of democracy and the violence perpetrated against cis and trans women in the country. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Brazil ranks fifth in the world in femicide rates; Guatemala ranks even higher, and other Latin American countries also appear on that list, highlighting the urgent need for transformation. The flowers allude to a possible social awakening, while the choice of gravediggers to place them around her body refers to the victims of femicide in Brazil. This is, therefore, a double operation that challenges democratic states and their supposed guarantee of human rights in territories plagued by multiple instances of violence.

In her artistic practice, which focuses primarily on performance, Galindo explores the possibilities of fabulation that this hybrid language allows. It confronts figures of power and rigid social structures, sometimes proposing absurd scenarios that challenge everyday reality. This is how a magical dialogue between worlds takes place, where her seemingly fragile body becomes something immense. This exercise connects with the deep roots of these territories and can provoke minds exhausted by social inequality to imagine possible revolutions.

Works such as Jardin de Flores [Flower Garden] (2021) and Guatemala Feminicida [Femicidal Guatemala] (2021), included in the exhibition, activate the public space with the presence of the female body, calling for critical attention and reflection on the living conditions of these people. In Jardin de Flores, by covering the bodies of 25 trans women with colorful fabrics, Galindo removes the viewer from a stigmatizing gaze while affirming their existence. In Guatemala Feminicida, she walks the streets with a flag similar to the Guatemalan one but in black and white, marching like a survivor, although mourning the deaths of so many of us.

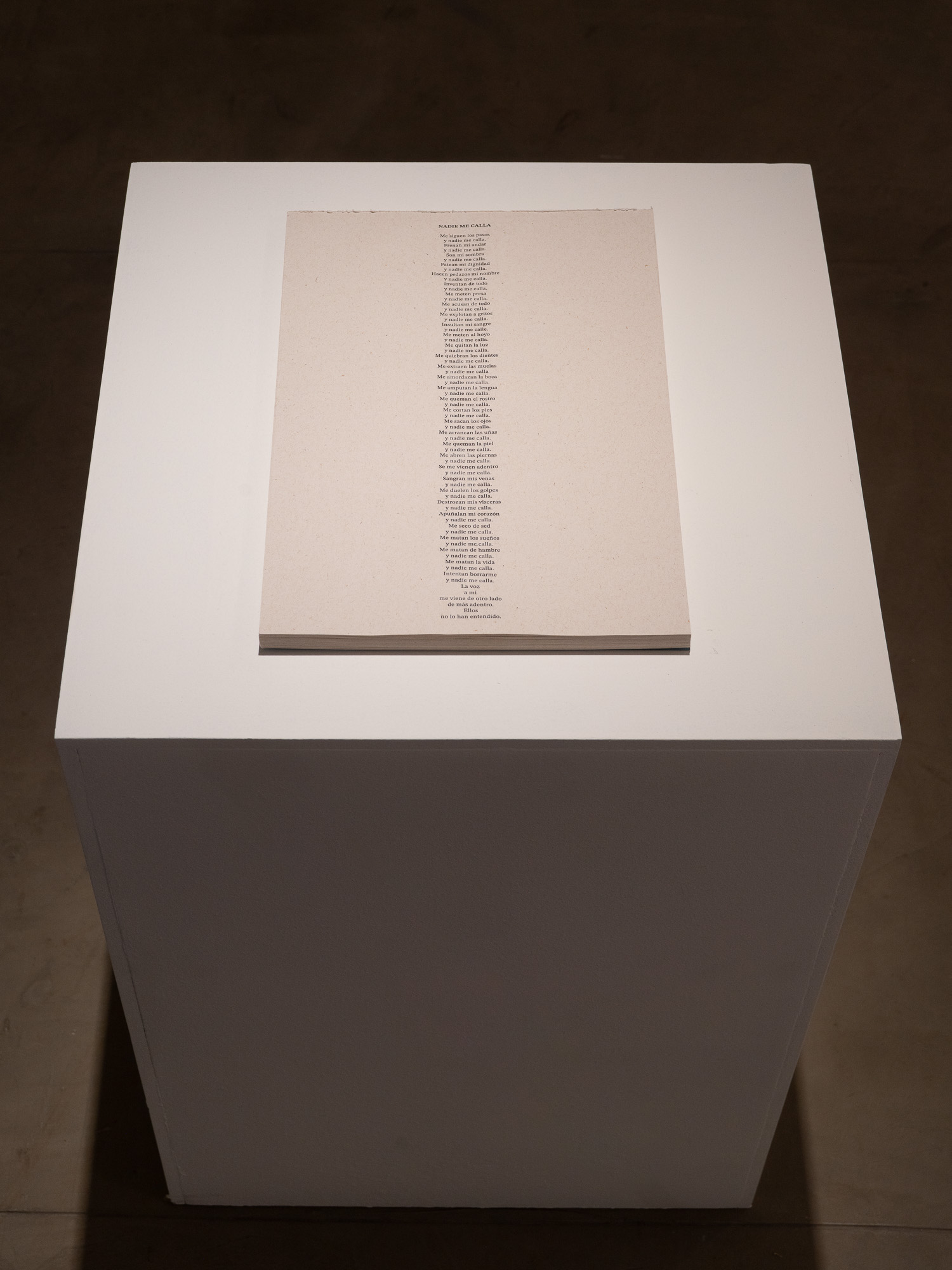

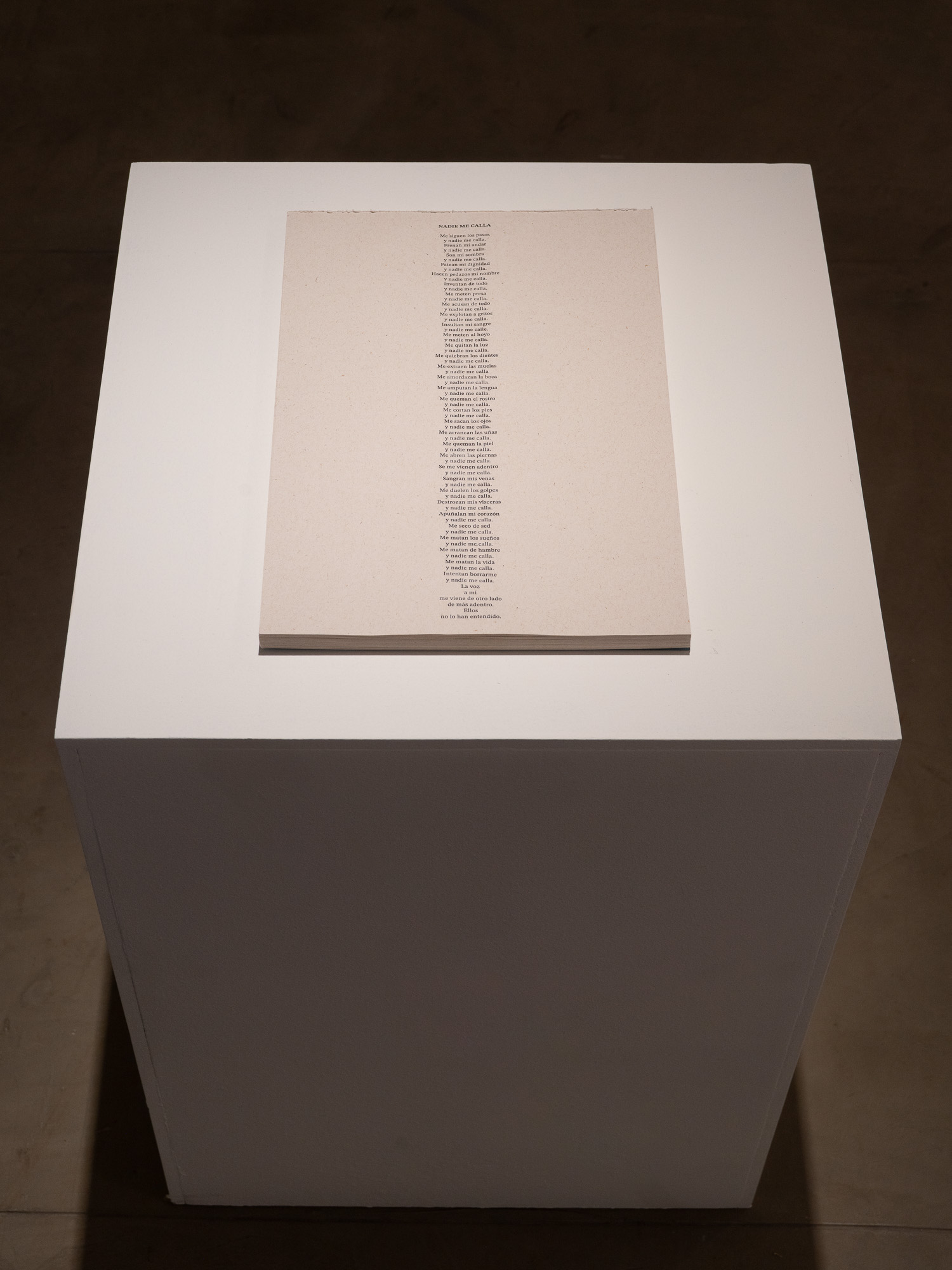

The exhibition also includes La sangre del cerdo [The Pig's Blood] (2017), Rios de gente [Rivers of People], El gran retorno [The Great Return], and the poem Nadie me calla [Nobody Silences Me]. It is interesting to note that Galindo always presents herself as an artist and poet, emphasizing the importance of language and the poetic word in her work. The aforementioned poem, displayed in a white cube from which the public can take a copy, seems to shout from the gallery walls: “Her body will not be silent, her memory will not be silent, her dreams will not be silent.” This is a statement that transcends time: the artist born in the context of war in her home country refuses to be silenced by it, even though today that conflict takes other forms—those shaped by these democracies marked by multiple setbacks.

For those who are not yet familiar with her work, this exhibition offers an overview of her production over the last decade, showcasing both her versatility and the unique grammar that defines her works. Her treatment positions Regina Jose Galindo as an artist committed to the struggles of peoples violated by states and their structures, particularly patriarchal violence, as well as those emanating from Eurocentric perspectives of domination. In the same way, it stretches the imaginary of borders and geographical limits invented by men, expanding the horizon of what is imposed as imperative: rivers, flowers, blood, poetry, desire, and many other subjective elements that live and persist beyond the limits of the human species.

At a conference held at the Tomie Ohtake Institute in 2021, Galindo was asked how she deals psychologically with what she experiences in her works. She answered clearly: “The biggest problem is the research process, when I'm faced with reality.” That is to say, no performance impacts her as much as direct contact with the realities of rights violations. Her practices are a space of struggle in which poetics becomes a powerful weapon. When they take place in public spaces, they acquire an impact that is often difficult to measure, generating powerful and disruptive images in everyday life, as in Rios de gente, which updates the community memory of a river diverted from its course. In more intimate or closed spaces, her actions shock the audience, such as in La sangre del cerdo, where she is doused with a bucket of pig's blood in allusion to Donald Trump's American policy.

In some public interventions, the artist has stated that she often doesn't conceive her works as artistic pieces, but rather as a cry that cannot be postponed. In her work, there is a notion of reality that calls for action, but also great courage in mobilizing communities to make her performances possible. The relevance of her works is striking, revealing how her production engages with a global axiom sustained "at the cost of many people’s blood". In Primavera Democratica, Regina offers us flowers while inviting us to question what democracy means and what kind of society we want to inhabit.

It's often said that her actions are radical; however, given the issues she addresses in her research, how can one not be radical when confronting the legacy of colonial violence in the Americas? It seems that Galindo uses a force equivalent to the violence she exposes. In order to shake and break structures rooted in our subjectivities, an equally forceful response is necessary. By incorporating these ideas into her performances, she puts her body into play and establishes a dialogue between apparent fragility and the great symbols of power: the street, public buildings, war tanks, crowds, and men.

The urgency of Regina Jose Galindo's work is revealed in the current global context, marked by socioeconomic crises and the advance of totalitarian policies that accompany a conservative wave. In the Primavera Democratica performance, she may be dreaming, making her nakedness and existence a place to imagine life. At a time when many fields of art seem to remain silent in the face of ongoing genocides, Regina Jose Galindo refuses to accept omission as an option. In this way, she reminds us that art is always political, whether in the impertinence of staying alive in front of a war tank, or in silence in the face of barbarism.

Although the borders between countries are limits imposed by human invention, there is something that connects us as "Latin Americans", a term that in itself highlights the impact and legacy of colonialism in our territories. Beyond this colonial fiction, there are multiple confluences between the countries of so-called Latin America, territories that Regina Jose Galindo has researched and explored through her artistic practice, composed mostly of performances. Born in 1974 in Guatemala City, where she lives and works, Galindo is one of the most internationally recognized artists in the field of performance art. She has received important accolades, such as the Golden Lion at the 51st Venice Biennale in 2005.

Her artistic production stretches that which unites us while exposing still-open social wounds, using themes such as politics, gender, and democratic setbacks as fundamental axes of her research. Her work is part of important collections around the world and she has participated in prominent international exhibitions such as the São Paulo, Prague and Istanbul biennials, as well as institutions such as the Tate Modern (London), the Centre Pompidou (Paris) and the Guggenheim (New York), among others. With a career spanning more than two decades, her work not only denounces but also calls for change.

In Primavera Democratica, presented at Portas Vilaseca in Rio de Janeiro as part of the gallery's 15th anniversary commemorative calendar, Regina Jose Galindo brings together a series of works created from 2017 to the present. This is the first time the Brazilian city has hosted a solo exhibition by the artist. For the occasion, Galindo conceived and carried out an unprecedented on-site performance entitled Primavera Democratica [Democratic Spring], which also gives its name to the exhibition. In addition to the performance at Praça da Harmonia in downtown Rio, the gallery organized a public conversation between Galindo and Guatemalan artist Jorge de Leon, in which they shared with the public aspects of their respective careers, marked by significant performances in contemporary art.

Curated by Daniela Labra, the exhibition occupies two floors of the gallery. At the entrance, the visitor encounters a photographic record of Primavera Democratica. The performance is also documented on video, where Regina is seen lying naked on the ground while two gravediggers place wildflowers around her body. For a few minutes, the flowers form a sort of tapestry or deathbed, with the artist motionless and with her eyes closed at the center. People passing through the space stop to observe, evoking the sensation of being at a wake. However, one can also think: What does a body like that dream about? What possibilities of existence does a woman have?

The title of the work, as well as the exhibition, was conceived specifically for the Brazilian context, considering the discussions surrounding the limits of democracy and the violence perpetrated against cis and trans women in the country. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Brazil ranks fifth in the world in femicide rates; Guatemala ranks even higher, and other Latin American countries also appear on that list, highlighting the urgent need for transformation. The flowers allude to a possible social awakening, while the choice of gravediggers to place them around her body refers to the victims of femicide in Brazil. This is, therefore, a double operation that challenges democratic states and their supposed guarantee of human rights in territories plagued by multiple instances of violence.

In her artistic practice, which focuses primarily on performance, Galindo explores the possibilities of fabulation that this hybrid language allows. It confronts figures of power and rigid social structures, sometimes proposing absurd scenarios that challenge everyday reality. This is how a magical dialogue between worlds takes place, where her seemingly fragile body becomes something immense. This exercise connects with the deep roots of these territories and can provoke minds exhausted by social inequality to imagine possible revolutions.

Works such as Jardin de Flores [Flower Garden] (2021) and Guatemala Feminicida [Femicidal Guatemala] (2021), included in the exhibition, activate the public space with the presence of the female body, calling for critical attention and reflection on the living conditions of these people. In Jardin de Flores, by covering the bodies of 25 trans women with colorful fabrics, Galindo removes the viewer from a stigmatizing gaze while affirming their existence. In Guatemala Feminicida, she walks the streets with a flag similar to the Guatemalan one but in black and white, marching like a survivor, although mourning the deaths of so many of us.

The exhibition also includes La sangre del cerdo [The Pig's Blood] (2017), Rios de gente [Rivers of People], El gran retorno [The Great Return], and the poem Nadie me calla [Nobody Silences Me]. It is interesting to note that Galindo always presents herself as an artist and poet, emphasizing the importance of language and the poetic word in her work. The aforementioned poem, displayed in a white cube from which the public can take a copy, seems to shout from the gallery walls: “Her body will not be silent, her memory will not be silent, her dreams will not be silent.” This is a statement that transcends time: the artist born in the context of war in her home country refuses to be silenced by it, even though today that conflict takes other forms—those shaped by these democracies marked by multiple setbacks.

For those who are not yet familiar with her work, this exhibition offers an overview of her production over the last decade, showcasing both her versatility and the unique grammar that defines her works. Her treatment positions Regina Jose Galindo as an artist committed to the struggles of peoples violated by states and their structures, particularly patriarchal violence, as well as those emanating from Eurocentric perspectives of domination. In the same way, it stretches the imaginary of borders and geographical limits invented by men, expanding the horizon of what is imposed as imperative: rivers, flowers, blood, poetry, desire, and many other subjective elements that live and persist beyond the limits of the human species.

At a conference held at the Tomie Ohtake Institute in 2021, Galindo was asked how she deals psychologically with what she experiences in her works. She answered clearly: “The biggest problem is the research process, when I'm faced with reality.” That is to say, no performance impacts her as much as direct contact with the realities of rights violations. Her practices are a space of struggle in which poetics becomes a powerful weapon. When they take place in public spaces, they acquire an impact that is often difficult to measure, generating powerful and disruptive images in everyday life, as in Rios de gente, which updates the community memory of a river diverted from its course. In more intimate or closed spaces, her actions shock the audience, such as in La sangre del cerdo, where she is doused with a bucket of pig's blood in allusion to Donald Trump's American policy.

In some public interventions, the artist has stated that she often doesn't conceive her works as artistic pieces, but rather as a cry that cannot be postponed. In her work, there is a notion of reality that calls for action, but also great courage in mobilizing communities to make her performances possible. The relevance of her works is striking, revealing how her production engages with a global axiom sustained "at the cost of many people’s blood". In Primavera Democratica, Regina offers us flowers while inviting us to question what democracy means and what kind of society we want to inhabit.

It's often said that her actions are radical; however, given the issues she addresses in her research, how can one not be radical when confronting the legacy of colonial violence in the Americas? It seems that Galindo uses a force equivalent to the violence she exposes. In order to shake and break structures rooted in our subjectivities, an equally forceful response is necessary. By incorporating these ideas into her performances, she puts her body into play and establishes a dialogue between apparent fragility and the great symbols of power: the street, public buildings, war tanks, crowds, and men.

The urgency of Regina Jose Galindo's work is revealed in the current global context, marked by socioeconomic crises and the advance of totalitarian policies that accompany a conservative wave. In the Primavera Democratica performance, she may be dreaming, making her nakedness and existence a place to imagine life. At a time when many fields of art seem to remain silent in the face of ongoing genocides, Regina Jose Galindo refuses to accept omission as an option. In this way, she reminds us that art is always political, whether in the impertinence of staying alive in front of a war tank, or in silence in the face of barbarism.