The artist Laryssa Machada writes about "Aqui e Ali", the first solo exhibition of artist Agrippina Manhattan in the city of Rio de Janeiro. The destabilization of maps and the linguistic strategies that accompany Manhattan’s research process once again emerge as counter-narrative tools against the white-cishetero-colonial world—the very one that upholds the art world.

São Gonçalo, the artist's homeland, appears as the gravitational center of the exhibition. Aqui e Ali [Here and There], Agrippina Manhattan's first solo exhibition at the Artur Fidalgo Gallery, is a cartographic gesture that rejects fixed borders. Living on the edge of Brazil's second-largest metropolis, yet simultaneously focusing on her backyard, her image, the house won by her grandmother in a legal battle; tracing a meridian in São Gonçalo.

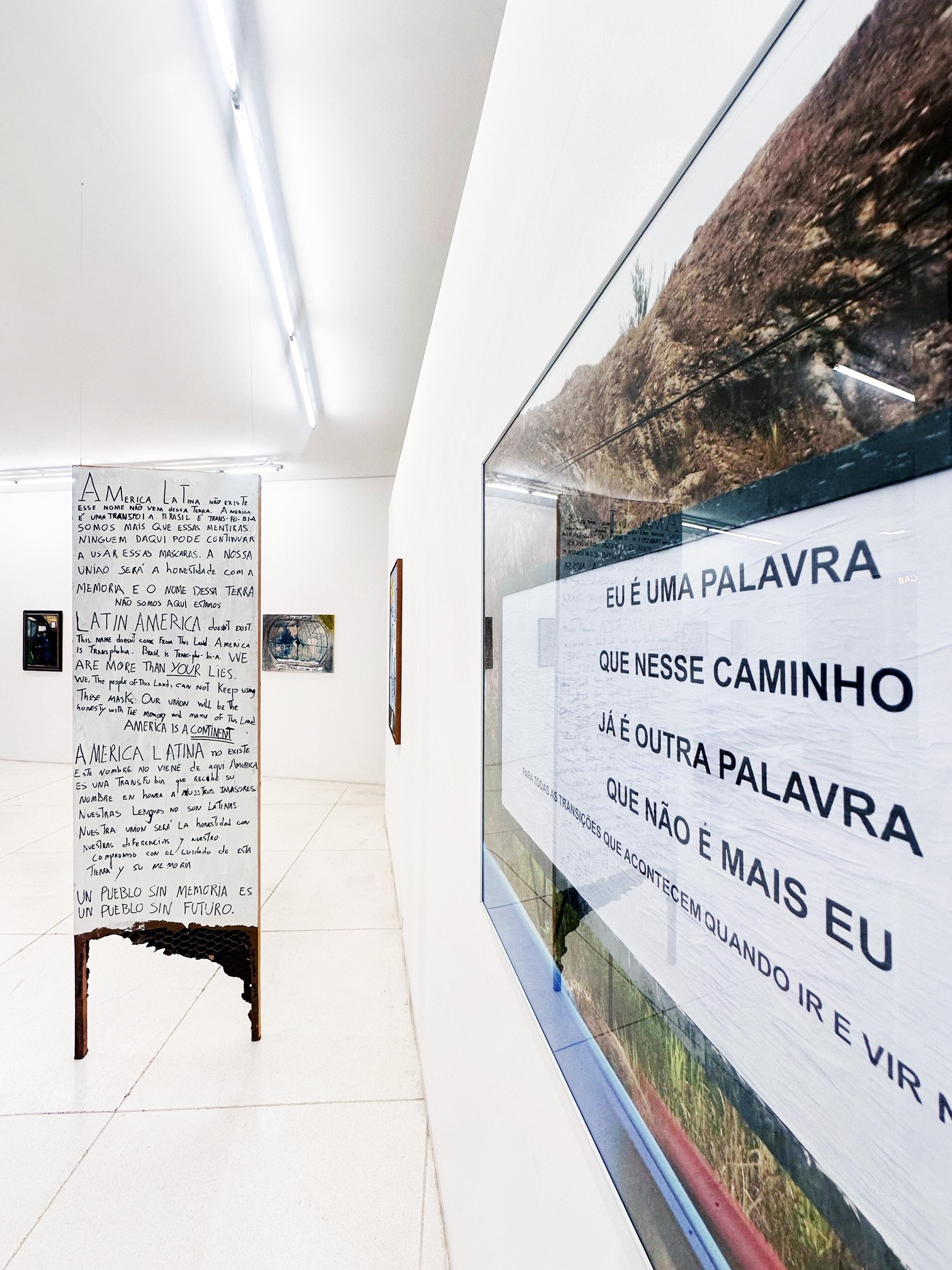

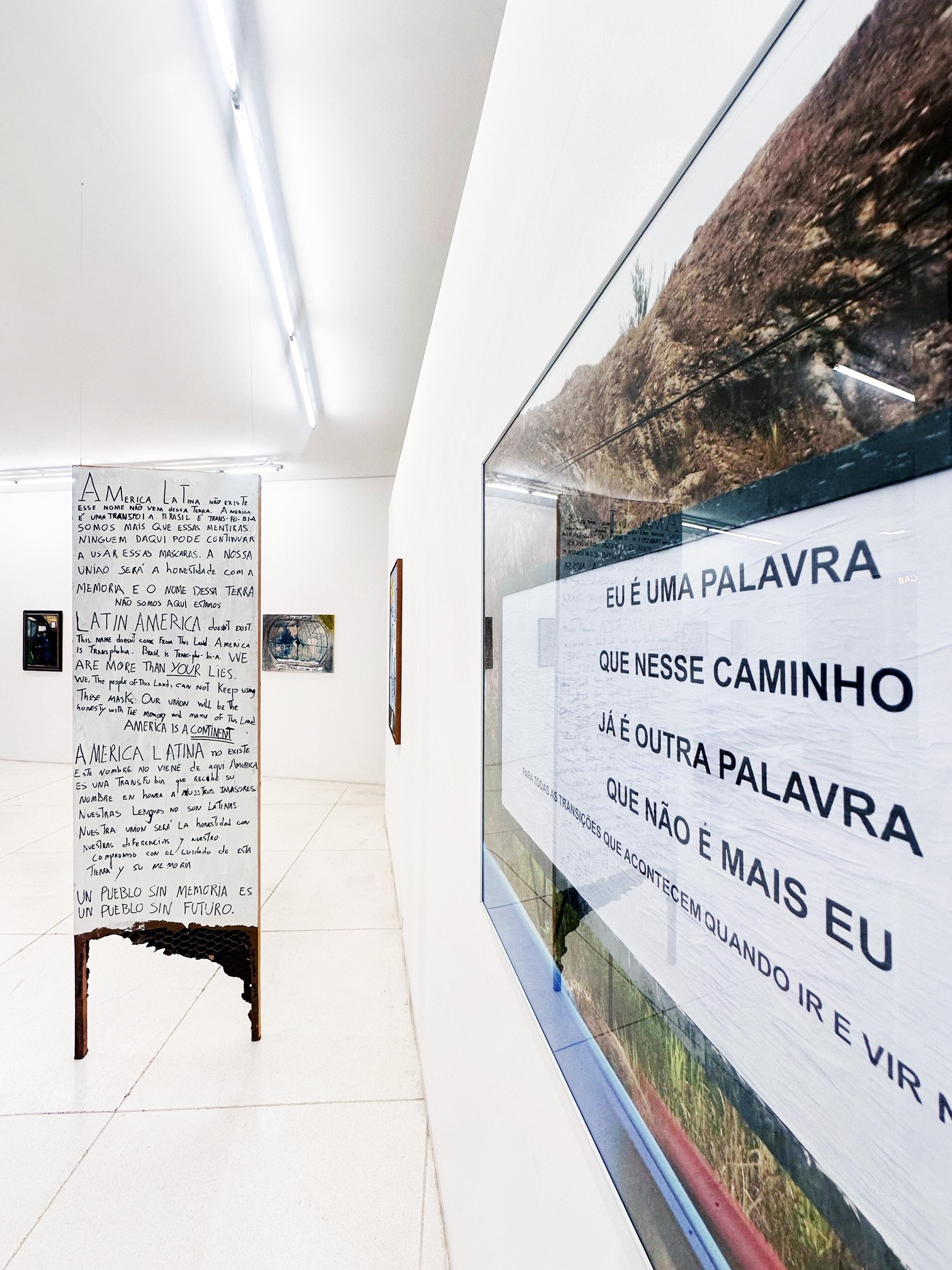

Semiotically and corporally, Agrippina proposes a destabilization of maps. She physically moves through the city, transitioning points of view: “Among the most recent works is the door, which I call Velhas Linguas, Novas Mentiras [Old Languages, New Lies]. Which, like every door, has two sides. In it I wrote a text that switches between Spanish, Portuguese and English. On the back it says: “Não sou blanca, papi. Sou latina, papi. Saoko”. The phrase, a reappropriation of Rosalía's song (which in turn reinterprets an Afro-Caribbean sound), is a serious joke: What place is this so-called Latin America? Who decides the legitimacy of these territories? The Transição [Transition] videoperformance narrates precisely that border in a more subjective sphere.

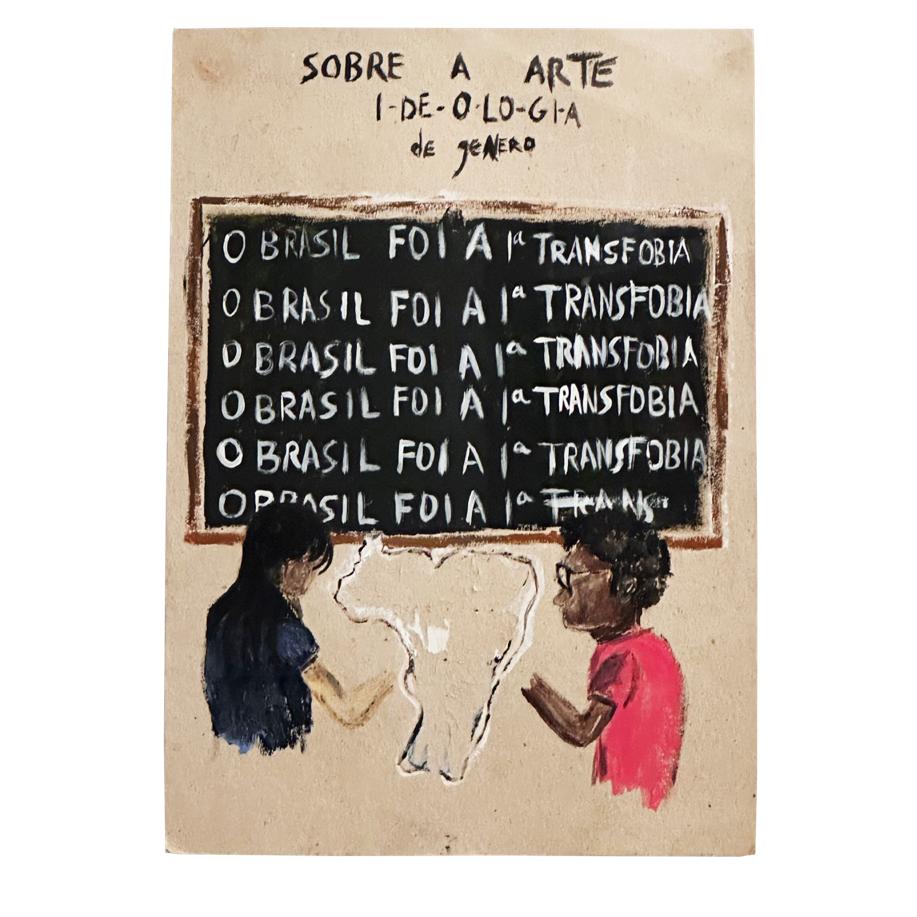

In the same rhythm, on a moving and affective axis, the artist traces Leviathan, a ferocious creature that crosses oceans. And he lands in those nations with solid surfaces, but burning inside. In this way, the territory does not appear as a neutral inheritance: the house she inherited in São Gonçalo also appears as a debt, as a collapsing roof, a staircase to be rebuilt. “But it’s my house,” says Agrippina. Checking the “Brazilian” soil is like realizing you’ve received a house, but you still have to deal with the holes. As a solo exhibition, Manhattan manages to complicate its narrative, stitching together a contradictory History of Art—which, incidentally, is the artist's academic background.

Two of her earlier works directly exemplify this pictorial revision: Praia das Pedrinhas and O Último Missionário [Rock Beach and The Last Missionary] establish a direct confrontation with the history of 19th-century Brazilian art. The works are based on the paintings Moema, by Victor Meireles, and O Último Tamoio, by Rodolfo Amoedo, both made by white men who, consciously or unconsciously, perpetrated images of dejected indigenous bodies. In Manhattan's reinterpretation, she inserts her own body as a mediator: “When I came to these works, I thought about how to replace those indigenous bodies with respect. And my respect was not wanting to represent something that I am not.” In Praia das Pedrinhas, she exchanges the idyllic setting for a landscape of São Gonçalo and portrays herself sunbathing topless—a gesture that interrupts the logic of exoticization and reinscribes a present, self-narrative body that is not subordinated to the colonial myth. Already in O Último Missionário, the inversion of the scene draws a symbolic rupture: it is not just a question of replacing a character, but of exposing the failure of a civilizing project. Both works displace the place of homage and operate as visual critique, proposing an ethical and aesthetic reconfiguration of national imaginaries.

Official history, Bible, world map, pop music: Old Lies documented and transported through the centuries, renewed in the present: “That work came about when I saw that Rosalia won a Latin Grammy. That discussion about where things come from. Sometimes a symbol changes location, culture, and context so much that it transforms into something else. I never imagined exhibiting that work, which is why it has a comical honesty.”

In Other Borders, fire appears as the courage to lose absolute control over the transformation of the fabric—and to expose the unpredictable, the unknown, that which is still difficult to translate. “He doesn’t respect the line, he doesn’t respect those borders,” memories that can no longer even be accessed. “I, for one, am somewhat pessimistic. I believe that which is not remembered is lost. So, it's a right, a compensation, which is much more than just land, you know?”

Before Aqui e Ali, the artist had already been constructing narratives between art and education, body and territory, image and discourse. In previous works, such as the collective exhibitions Rio de Corpo e Alma and Ainda Trago na Boca, her research on canons, language and pedagogy was already presented in a structured manner. What the current exhibition does is consolidate these themes into a more concentrated space, where it is possible to perceive the continuity of a living visual experimentation—shaped in friction with art history.

Agrippina Manhattan, born on the São Gonçalo meridian, draws herself with the Atlas in her hand: “That's a practice that has interested me, placing my references as the official ones of Art History.” After all, maps fail loudly.

Agrippina R. Manhattan was born and raised in São Gonçalo since 1997. She studied Art History at the EBA-UFRJ and Visual Arts at the EAV Parque Lage. She presents herself as an artist, teacher and transvestite because these are things she wanted to become. She is interested in conceptual art, the beauty of words, and emancipatory strategies in education. She participated in the collective exhibitions Rio de Corpo e Alma at the Historical Museum of the City (RJ) and Ainda Trago na Boca at the Christal Galeria (PE). She has lived in Recife since winning the VI FUNDAJ Artist-in-Residence Competition in 2023.

São Gonçalo, the artist's homeland, appears as the gravitational center of the exhibition. Aqui e Ali [Here and There], Agrippina Manhattan's first solo exhibition at the Artur Fidalgo Gallery, is a cartographic gesture that rejects fixed borders. Living on the edge of Brazil's second-largest metropolis, yet simultaneously focusing on her backyard, her image, the house won by her grandmother in a legal battle; tracing a meridian in São Gonçalo.

Semiotically and corporally, Agrippina proposes a destabilization of maps. She physically moves through the city, transitioning points of view: “Among the most recent works is the door, which I call Velhas Linguas, Novas Mentiras [Old Languages, New Lies]. Which, like every door, has two sides. In it I wrote a text that switches between Spanish, Portuguese and English. On the back it says: “Não sou blanca, papi. Sou latina, papi. Saoko”. The phrase, a reappropriation of Rosalía's song (which in turn reinterprets an Afro-Caribbean sound), is a serious joke: What place is this so-called Latin America? Who decides the legitimacy of these territories? The Transição [Transition] videoperformance narrates precisely that border in a more subjective sphere.

In the same rhythm, on a moving and affective axis, the artist traces Leviathan, a ferocious creature that crosses oceans. And he lands in those nations with solid surfaces, but burning inside. In this way, the territory does not appear as a neutral inheritance: the house she inherited in São Gonçalo also appears as a debt, as a collapsing roof, a staircase to be rebuilt. “But it’s my house,” says Agrippina. Checking the “Brazilian” soil is like realizing you’ve received a house, but you still have to deal with the holes. As a solo exhibition, Manhattan manages to complicate its narrative, stitching together a contradictory History of Art—which, incidentally, is the artist's academic background.

Two of her earlier works directly exemplify this pictorial revision: Praia das Pedrinhas and O Último Missionário [Rock Beach and The Last Missionary] establish a direct confrontation with the history of 19th-century Brazilian art. The works are based on the paintings Moema, by Victor Meireles, and O Último Tamoio, by Rodolfo Amoedo, both made by white men who, consciously or unconsciously, perpetrated images of dejected indigenous bodies. In Manhattan's reinterpretation, she inserts her own body as a mediator: “When I came to these works, I thought about how to replace those indigenous bodies with respect. And my respect was not wanting to represent something that I am not.” In Praia das Pedrinhas, she exchanges the idyllic setting for a landscape of São Gonçalo and portrays herself sunbathing topless—a gesture that interrupts the logic of exoticization and reinscribes a present, self-narrative body that is not subordinated to the colonial myth. Already in O Último Missionário, the inversion of the scene draws a symbolic rupture: it is not just a question of replacing a character, but of exposing the failure of a civilizing project. Both works displace the place of homage and operate as visual critique, proposing an ethical and aesthetic reconfiguration of national imaginaries.

Official history, Bible, world map, pop music: Old Lies documented and transported through the centuries, renewed in the present: “That work came about when I saw that Rosalia won a Latin Grammy. That discussion about where things come from. Sometimes a symbol changes location, culture, and context so much that it transforms into something else. I never imagined exhibiting that work, which is why it has a comical honesty.”

In Other Borders, fire appears as the courage to lose absolute control over the transformation of the fabric—and to expose the unpredictable, the unknown, that which is still difficult to translate. “He doesn’t respect the line, he doesn’t respect those borders,” memories that can no longer even be accessed. “I, for one, am somewhat pessimistic. I believe that which is not remembered is lost. So, it's a right, a compensation, which is much more than just land, you know?”

Before Aqui e Ali, the artist had already been constructing narratives between art and education, body and territory, image and discourse. In previous works, such as the collective exhibitions Rio de Corpo e Alma and Ainda Trago na Boca, her research on canons, language and pedagogy was already presented in a structured manner. What the current exhibition does is consolidate these themes into a more concentrated space, where it is possible to perceive the continuity of a living visual experimentation—shaped in friction with art history.

Agrippina Manhattan, born on the São Gonçalo meridian, draws herself with the Atlas in her hand: “That's a practice that has interested me, placing my references as the official ones of Art History.” After all, maps fail loudly.

Agrippina R. Manhattan was born and raised in São Gonçalo since 1997. She studied Art History at the EBA-UFRJ and Visual Arts at the EAV Parque Lage. She presents herself as an artist, teacher and transvestite because these are things she wanted to become. She is interested in conceptual art, the beauty of words, and emancipatory strategies in education. She participated in the collective exhibitions Rio de Corpo e Alma at the Historical Museum of the City (RJ) and Ainda Trago na Boca at the Christal Galeria (PE). She has lived in Recife since winning the VI FUNDAJ Artist-in-Residence Competition in 2023.