19.09.2019

Por Kati Lincopil

Santiago de Chile

26 de julio de 2019 – 13 de octubre de 2019

Una de las sedes del Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Santiago de Chile está ubicada en el Parque Forestal, en la ribera sur del río Mapocho, en el centro mismo de la ciudad. Familias de distinta conformación, tamaño y nacionalidad aprovechan para pasear. Algunas renuncian a la tarde soleada para explorar el frío interior del MAC, el siamés impopular del Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, con el cual comparte edificio.

En la primera planta se encuentra Si tú vivieras aquí, la primera retrospectiva de la artista estadounidense Martha Rosler (Brooklyn, 1943) en Latinoamérica, curada por Mariagrazia Muscatello y Montserrat Rojas Corradi, en el marco de la segunda edición de BIENALSUR —la Bienal Internacional de Arte Contemporáneo de América del Sur. Así lo anuncian las grandes letras blancas inscritas al exterior de la sala 1, junto a una lista de las y los artistas nacionales invitadas e invitados a dialogar: Claudia del Fierro, Cristóbal Cea, Bárbara Oettinger, Bernardo Oyarzún, Voluspa Jarpa y Máximo Corvalán-Pincheira.

“¿Quién es Martha Rosler?”, se preguntan al oído algunos de los que se animaron a entrar al museo. Al cruzar el umbral se encuentran con In the place of the public: Airport, que ocupa los dos primeros muros que colindan en ángulo recto. Ocho fotografías de la serie, que muestran los lúgubres interiores de aeropuertos de EE.UU. y Alemania, fronteras higiénicas y estandarizadas, están montadas en línea horizontal sobre ambos muros blancos, rodeadas de frases de distintos tamaños, en letras negras, como si flotaran:

control total

imagen brillante de desalojo

regímenes del escrutinio

No digo mapa, no digo territorio

fantasías de escape

Más a la izquierda una pantalla plana reproduce un slide de fotos del proyecto aún en curso Air Fare, una serie de capturas de comidas ofrecidas en vuelos de primera clase, deformes miniaturas, versiones patéticas e industrializadas, de tablas de queso y uvas, pato a la naranja, crême brûlée. Porciones casi inexistentes de caviar acompañadas de copitas de champaña, que la baja calidad de las tomas vuelven aún más deprimentes y ridículas.

Dos mujeres muy jóvenes, una de cabello corto y rosado y otra de melena azul, se detienen frente al televisor por unos momentos, cuchichean brevemente, y se dirigen con impaciencia a la banca de madera dispuesta frente a un antiguo televisor que reproduce el video de 1983, A simple case for torture, or how to sleep at night. Los dos auriculares conectados son ocupados por una mujer y su pequeño hijo. El niño tiene apenas tres años, la madre intenta empecinadamente ponerle los audífonos y, con acento venezolano, le pide que se quede tranquilo. Luego de que logra acomodarlo, miran por unos momentos las manos de Rosler moviendo y superponiendo recortes de prensa escrita sobre la intervención de EE.UU. en Latinoamérica, la que propició los golpes de Estado, denunciando su apoyo implícito a la tortura, las violaciones a los derechos humanos. En una hora de grabación, Rosler muestra una documentación bibliográfica exhaustiva de las consecuencias políticas y económicas en dichos países, la manipulación de la información y la soberbia estadounidenses. Paralelamente, la voz de un hombre expone en inglés sobre filosofía y política. El video no cuenta con subtítulos.

En la sala se escucha un golpe estrepitoso que hace que varias personas se distraigan de la lectura de las reproducciones ampliadas de Tijuana maid (texto original de 1978 y readaptado este año), una de las Novelas postales de Service: A trilogy on colonization, en la que una mujer mexicana que emigra de Tijuana a San Diego relata, en primera persona, la experiencia de cruzar la frontera ilegalmente, para luego ejercer como criada, siendo víctima de abusos y discriminación, mientras, paralelamente, es objeto de exotización y motivo de presunción por parte de sus empleadores. “Will you cook a Mexican dinner for us sometimes? / ¿Nos cocina una comida mexicana para nosotros alguna vez?”, dice en una de las postales que recoge fragmentos de recetas y frases comunes del Home maid Spanish cookbook, el bestseller bilingüe que intenta adiestrar al servicio doméstico hispanohablante en las costumbres de la American family. “A los ricos le gusta comer la comida de los pobres”, afirma la protagonista del relato. El testimonio problematiza cómo la extrema xenofobia colinda con la devoración cultural y física de los inmigrantes/invasores, recluidos y esclavizados en la intimidad de la familia burguesa.

El niño se encuentra en el suelo, los audífonos lejos, y la madre se apresura en levantarlo. Rosler sigue moviendo sus recortes en la pantalla, mostrando libros. La madre y el niño se alejan del intervencionismo, de la tortura, de la política y la filosofía.

La característica melodía de Star Wars que musicaliza el paródico video Chile on the road to NAFTA (1997), interpretada por la Banda Instrumental de la Escuela de Suboficiales de Carabineros, llena la sala. La luz de la proyección es débil y no logra sobreponerse a la iluminación del lugar. Las imágenes del Chile rural de los noventa y la gigantografía de un enorme brazo que empuña una lata de Coca-Cola, emplazado en medio de un eriazo, aluden a cómo Chile pasó de un gobierno socialista a volverse el “laboratorio neoliberal” de América Latina. Star Wars, el puño, carretas tiradas por mulas, las épicas trompetas, Coca-Cola. El montaje no puede sino provocar una risa melancólica.

Dos señoras se sorprenden al ver que la obra trata sobre Chile. Se sorprenden de verse producidas y observadas por la productora y observadora proveniente de EE.UU., el mirador mundial.

Claudia del Fierro (Santiago, 1974) ocupa la esquina sur oriente del museo, dando la espalda a la Cordillera de los Andes. Su obra Políticamente correcto (2001-2019) es una video performance reproducida en dos proyecciones simultáneas. En una, vemos a Del Fierro caminar por una vereda en dirección a la proyección vecina y luego regresar. En el segundo vemos cómo, vestida como una más de las costureras de una fábrica de ropa, logra entrar y salir del lugar junto al resto de las obreras, sin que nadie note que no trabaja ahí. Del Fierro se “disfraza” de obrera textil para entrometerse en su mundo. En el suelo, levemente iluminados, están apilados los uniformes, los disfraces. Afuera, una pantalla plana reproduce el montaje de imágenes de inmigrantes cruzando la frontera de países del primer mundo, intercaladas con violentos flashes rojos, que conforman la pieza Who said we did not know (2018) de Bárbara Oettinger (Santiago, 1981), la única artista que no se refiere a Chile. Junto a ella, las tres fotografías biométricas de un rostro “mestizo”, junto a una reproducción de un retrato hablado de rasgos similares, superan los dos metros de alto y son parte de la icónica obra Bajo sospecha de Bernardo Oyarzún (Los muermos, 1963). El rostro retratado en las gigantografías es el del artista, quien en 1998 fue detenido por Carabineros y acusado injustamente de haber cometido un asalto. Oyarzún reflexiona sobre la criminalización de sus rasgos mapuche, ofreciendo su rostro al escrutinio, al juicio. La presencia de esta obra recuerda que en Chile perdura el racismo y el clasismo consecuencia de la Colonia. Un eco en la cultura popular que apunta a ello es el programa de humor crítico Plan Z, que en los años noventa, parodiaba esta situación con un sitcom llamado Mapuches millonarios. Una contradicción absoluta en Chile. “A veces creo que debería teñirme el pelo negro y cambiarme el apellido”, se lamenta en una escena la criada blanca y colorina de la familia mapuche representada en Plan Z.

Oyarzún monta además 164 retratos fotográficos de personas con alguna filiación sanguínea consigo mismo titulados La parentela o por la causa. La tipificación racista del rasgo mapuche emerge en el puente de una nariz, la forma de un cuello, la carnosidad de los labios, el color de la piel, algo que por muchas generaciones fue y sigue siendo motivo de vergüenza. Tener cara de pobre, de criminal. Tener “cara de nana”, como le gritaron en una versión de Lollapalloza a la músico chilena Anita Tijoux.

En el muro un texto reza:

Tiene la piel negra,

como un atacameño

el pelo duro,

los labios gruesos

prepotentes

mentón amplio,

frente estrecha,

como sin cerebro.

Son las cicatrices de un pecado original. Los retratos son un espejo, nos reflejan. Su “parentela” es también la nuestra.

La cantidad de información escrita que contiene la siguiente sala podría conformar un enorme libro. Informe Rettig (2017), de Máximo Corvalán-Pincheira (Santiago, 1977), instala en el muro tres tomos del Informe de la Comisión de Verdad y Reconciliación intervenidos con fuego hasta casi su desaparición. La obra recupera los relatos de presos políticos en la dictadura chilena. Junto a ella, Secuenciación del azul marino (2017) y White page sequencing presentan hojas de la guía telefónica de Santiago y Nueva York, respectivamente. La primera, intervenida con acuarela azul, es una alegoría a las personas asesinadas por la dictadura al ser lanzadas al Océano Pacífico. Son las únicas piezas de la muestra que intentan explicarse y contextualizarse por medio de un texto inscrito sobre el muro, que algunos se detienen a leer, mirando las piezas de reojo. Junto a ellas, parte del proyecto de Voluspa Jarpa (Rancagua, 1971), La biblioteca de la no historia, trabaja en torno a la desclasificación por parte del Servicio Secreto de EE.UU. de más de 200 mil documentos que refieren a Chile. Una desclasificación clausurada: 70% de la información fue tachada, borrada, perpetuando el trauma.

Los espectadores rodean las obras, leen parcialmente. Un hombre mayor con lentes bifocales pega la nariz en los documentos, frunciendo el ceño. Ladea la cabeza. La información textual es inabarcable, como inabarcable es la historia del horror. Borrar, tachar, hundir los relatos y los nombres de los sujetos, en estas obras, alude a la desaparición y tortura de sus cuerpos, pero por otro lado, su deshumanización. Para la dictadura los sujetos deben ser otros, olvidar, o de lo contrario, desaparecer. El asesinato de los opositores es un intento desesperado por borrar su existencia, donde los ciudadanos y su historia son solo datos, versiones reemplazables. Pero recuperar los “datos” no es una enunciación vacía, es inscribir en el papel, y así, en la memoria, la presencia en el mundo de quienes se intentó extinguir. Es recordar y recuperar el lugar de lo único que nos queda de ellos.

Separada de las obras chilenas, la última sala vuelve al trabajo de Rosler. A medida que cae la tarde, la humedad del interior cala los huesos. Solo algunas personas logran llegar a este último momento. En esta sala predominan las obras que han sido clasificadas como feministas, pero desde la perspectiva cerrada del feminismo blanco, que ha homogeneizado la identidad de las mujeres cisgénero, dejando en segundo plano su inscripción social, étnica, territorial y de clase. Un lugar de enunciación de discursos y producción de imágenes que va más allá de la tematización de las obras o la instalación de los tópicos asociados a “lo femenino” en la misma, donde, como en estas obras, hay una visibilización crítica a estereotipos sexistas superficiales, sin una mayor reflexión al respecto.

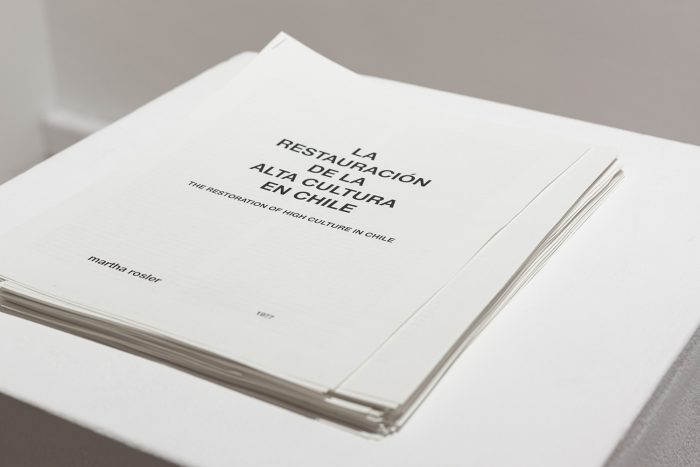

Las voces de la madre e hijo del video Domination and the everyday (1978) comparten espacio con los fotomontajes de la popular serie House beautiful: Bringing the war home (1967-1972), volviendo al tema de la invasión de los medios de comunicación en los espacios de intimidad, denunciando la indiferencia. Del poder sobre la información. Sobre un plinto un loop del paródico Semiotic of the kitchen (1975) es el único de los videos subtitulados al español, una pequeña fisura en la tiranía del inglés sobre las obras y las cédulas que atraviesa la muestra. En el otro extremo, Martha Rosler reads Vogue (1982), donde a través de los audífonos podemos oír la voz de la artista preguntando y respondiendo, mientras hojea la revista: “What is Vogue, what is fashion. It is glamour, it is excitement, drama, wishing…”. En otro muro comparten espacio las fotografías del cantautor Víctor Jara (San Ignacio, 1932) Manifestación en la vía pública (Vietnam Solidarity Campaign) de 1968 con el texto en español La restauración de la alta cultura en Chile (1977) de Rosler. El texto entrega una línea brutal: “La junta aparece en Televisión o por lo menos a los que tenían acceso a la televisión, luego del golpe —así lo afirma el New York Times— para recordarle a la gente de Chile: ‘Recuerden, ustedes pueden ser reemplazados’”. La obra convive espacialmente con fotografías de transeúntes y trabajadores de la serie Cuba (1981) y Chile (1995). Nosotros, los reemplazables.

Casi llegando a la salida del museo, como un tropiezo, arrinconado contra un pilar, se encuentra instalado en el suelo el video de Cristóbal Cea (Santiago, 1981), Hawker Hunter (v.1.1) (2015), una animación en 3D, reproducida en loop, del vuelo del avión británico con el que los militares bombardearon el Palacio de la Moneda el 11 de septiembre de 1973, y cuya cabina de control Cea recubre con lo que parece una enorme tela, boicoteando su trayectoria, su objetivo destructor, intentando impedir lo irreversible.

La tarde pre-primaveral acaba. En Santiago ya es de noche. La gente se enfunda en abrigos, rodea sus cuellos con bufandas. Abandona el silencio y los susurros para comentar lo experimentado mientras bajan la escalinata del museo. Rosler ha denunciado la indiferencia. ¿Nuestra indiferencia o la de ellos? Su obra respondió en su momento a una necesidad contextual, política, y se criticó su afán propagandístico, no-artístico. Ahora que sabemos, ¿podemos seguir igual? Afuera algunos se tientan con el olor a caramelo de un carrito de cabritas. [1] Saber no es suficiente si no se tiene poder sobre esa información. ¿Tenemos poder sobre esa información? Quizás tienen razón. Nosotros podemos ser reemplazados.

—

Kati Lincopil (Independencia, 1989) Estudió Teoría e Historia del Arte en la Universidad de Chile. Librera. Editora y co-fundadora en revistadesastre.cl

[1] Palomitas de maíz.

Palomitas de maíz

Comentarios

No hay comentarios disponibles.