25.01.2020

Sala de Exposiciones Planta Baja, Centro Cultural Tijuana, Tijuana

20 de septiembre de 2019 – 29 de marzo de 2020

It has been decades since we realized about media’s influence on our perception. However, it appears as if we still forget about this on a daily basis, and so we keep relating to our information devices as if they were transparent, faithful to reality, and completely harmless. The proof is in our tridimensional notion of space, in perspective representation, which was originally an invention of hegemonic knowledge; before the Renaissance, we didn’t see in perspective. [1] These visual production techniques have built the world as we know it, giving form not only to our way of perceiving reality as for its geometrical representation but our way of feeling and understanding it, instrumentalizing our desires and fears for the benefit of capital accumulation.

Inside this aesthetical indoctrination, the body, as a constitutive unity of power, carries with cosmetic and ideological mandates that result in certain ways of looking and behaving. In the specific case of sexual dissent, the LGBTTTIQA+ community has fought for the visibility and agency they currently have. Our presence in areas such as legislation, art, and entertainment, becomes a struggle for vindication as a form of assimilation by the dominant production system. The homosexual man has specifically reached global representation, not as a dissident, but as a variation of heterosexual men. Sheltered by liberal ideologies with progressive dyes, the gay men is now a sophisticated feminist, environmentalist, but most importantly, not a woman. The global representation of a gay man looks like a “man,” moves like a “man,” speaks like a “man.” He is white, fit, and handsome. The cost for this portrayal inside the system is the delimitations of the possibilities of being; being a gay man now is respectable, only if you are the gay the power needs and wants. The diversity discourse is always co-opted by the heteronormativity.

The misogynist discrimination that exists towards the insides of the LGBTTTIQA+ community, a consequence of the filtration of the acceptable gay paradigm, is the subject that Mauricio Muñoz develops in his exhibition MASC4Mascara at the Centro Cultural Tijuana (Tijuana, México). The exhibition consists of a space intervention, composed of video works, neon signs, and lightboxes. The pieces are united by LED laces which delineate the exhibition space and the museographical devices, creating a virtual like atmosphere, just like a Tron scene; a design that reflects the condition of most virtual habitability possibilities, which continue to reproduce the perspective and Cartesian planning implanted by the hegemonic epistemic regime. This feeling of cohabiting a video game—in which our vital integrity is at stake—is in line with Muñoz’s proposal, which seeks to materialize the digital space of gay mobile applications, using the graphic language of emojis and the visuality of global pop culture, such as the video clip.

Exhibition view of MASC4mascara by Mauricio Muñóz at Centro Cultural Tijuana. Image courtesy of the artist

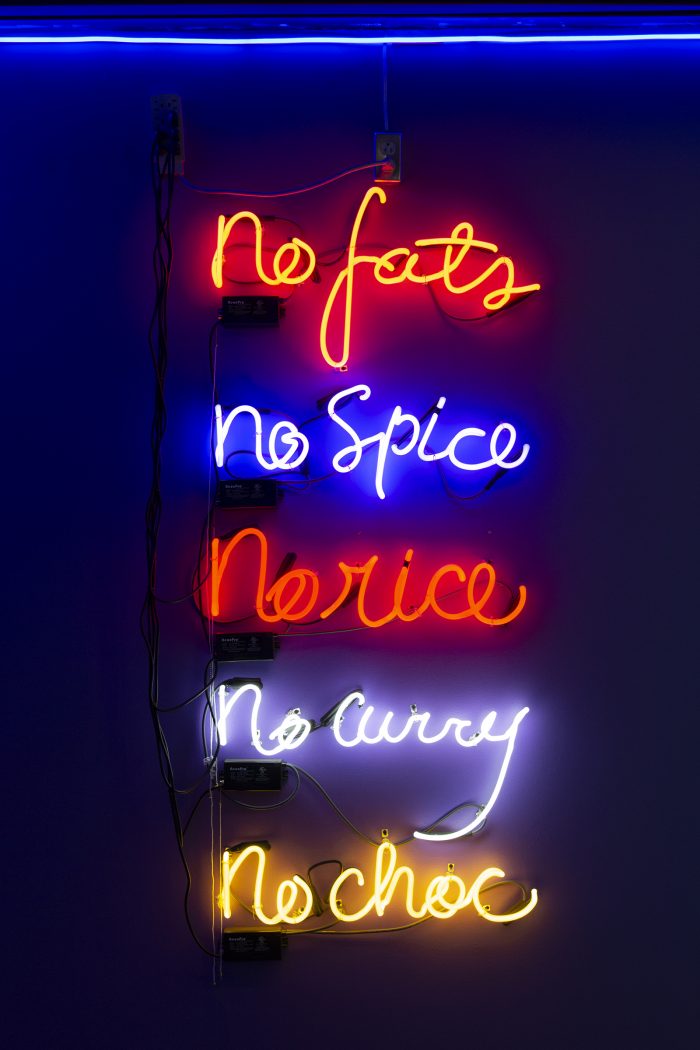

The eggplant and peach emojis, which are used to allude the penis and butt cheeks in social media language, are presented in the racial variety that the smartphone’s keyboard deploys in other emojis related to body parts, disarticulating the neutrality of the symbols by giving them a skin tone from white to black, going through redhead. Likewise, a shopping list written in neon light describes no fats, no spice, no rice, no curry, no choc, as the unwanted inputs, which actually refer to the racial diversity construct that marks bodies to categorize them as undesirable corporalities in application profiles. Without racialization, there is no sexualization. [2]

The aesthetical canons are systematically standardized constructs with the objective of defining valid and valuable bodies as opposed to the Other: fearsome and disposable. Managing this binary condition (fat-fit, handsome-ugly, poor-rich, white-black), structures the desire in such a way that we aspire to be those homogeneous bodies which embody the ideal gay, while we disregard all which doesn’t resemble that concept, even in our own body, generating permanent and irresolvable frustration— capitalism’s real currency—since that, which prevents us from joining the beauty canon is, to a large extent, a constituent part of our corporality.

MASC4Mascara is read in a luminous sign, the work which gives title to the exhibition, lauding to a phrase used in gay apps (masc4masc) to describe that the profile user has a masculine personality and that he is in search of another man with the same characteristics, condemning feminine conducts. Once again, the virility imperative patent, which also reproduces misogyny, creates violent conduct against the bodies that, to the eyes of these men, are devalued because of being similar to a woman’s body. Muñoz plays with this sentence by changing MASC for mascara, referring to the cosmetic used to make eyelashes prettier.

Vista de la exposición MASC4mascara de Mauricio Muñoz en el Centro Cultural Tijuana. Imagen cortesía del artista

Vista de la exposición MASC4mascara de Mauricio Muñoz en el Centro Cultural Tijuana. Imagen cortesía del artista

The feminized and feminine bodies are the most abject subjects for the system: women, transgendered, transsexual, and other fluid gendered persons, suffer from violence when performing “femininities” among the binary look of those who consider them as characteristics of disgusting and disposable bodies. One of the projected video clips shows the lip-sync of the song Never Knew Love Like This Before by Stephanie Mills. In the foreground, on a pink background, Muñoz appears wearing a blonde-pink wig and clothes in purple tones, mimicking her body gestures with the voice of the interpreter. A certain rasquache [3] aesthetic is evident. Meaning, an obscene, brave visuality that breaks codes and paradigms from the outsider’s vision and the unpleasant construction of a classist society. Towards the video clip’s finale the shot opens, revealing the dirt floor on which the artist dances, and seconds later, the bottom mount falls—appearing to be an accident—and an almost wild (or rather poor) landscape is revealed. This sequence places Muñoz as a racialized, feminized and third world body, evidencing the tactics for the manufacture of the hegemonic visuality that has co-opted the diverse; a visuality that admits dissent taken from its context, surrounded by interchangeable scenery.

The exhibition bets for an aesthetic based on entertainment’s glamour, a strategy that attracts a diversity of spectators, who in response to their conditioning, because of the seemingly colorful and familiar language of social networks, are faced with the torsion of the sex-gender paradigm and its performative possibilities. Something that is appreciated in a society as machista as the Mexcian society where homo-lesbo-transphobia continues to erode freedom and life.

Vista de la exposición MASC4mascara de Mauricio Muñoz en el Centro Cultural Tijuana. Imagen cortesía del artista

The long journey to the first openly queer exhibition

The room text mentions that Mauricio Muñoz’s show is the “first openly queer-themed exhibition” [4] showed at the Centro Cultural Tijuana. I celebrate that the cultural institution with a bigger scope in the city is opening its doors to artistic proposals with the characteristics of MASC4Mascara. But at the same time, I think of the artists, managers, and organizations, whose work allowed this event. With the intention of doing a memoir recognition, I will briefly mention some of the places and initiatives that contemplated sexual dissent, art, and culture as a working engine in Tijuana:

In 1978 Emilio Velásquez Ruiz founded Emilio’s Coffee, the epicenter of cultural events since sexual dissent, as well as a stronghold against the HIV / AIDS pandemic. In the eighties, he founded the first gay newspaper in Tijuana, Frontera Gay.

The performance Art Pilgrimage (Sushi Gallery, 1988) by Gerardo Navarro, who transvestite toured the streets of San Diego, CA, performing a series of actions related to the border between Mexico and the US, where the genre is questioned as another border.

The Las Comadres (1988-1992) collective, which reflected on women from the border, their paradigms, sufferings, and violence. The members are Anna O’Cain, Carmela Castrejón, María Eraña, Lynn Susholtz, Emily Hicks, Cindy Zimmerman, Berta Jottar, María Kristina Dybbro-Aguirre, Kirsten Aaboe, Graciela Ovejero, Eloisa de León, Laura Esparza, Rocío Weiss, Frances Charteris, Yareli Arizmendi, Marguerite Waller, Aida Mancillas, and Ruth Wallen.

Max Mejía directed Frontera Gay since 1991, after Arte de Vivir (2004), a cultural magazine that talked about sexual dissent and art-related themes.

In 1994 Antonio Escalante, Emilio Velásquez, and Max Mejía founded the Cultural Gay Week. This first edition celebrated an art exhibition in La Capilla de Frida gallery and coffee shop. Later it was adopted by the Institute of Art and Culture of Tijuana. It is currently performed in different spaces.

The (trans)feminist and interdisciplinary collective La Línea (2002-2009), which produced publications and actions related to gender. Its members are Amaranta Caballero, Abril Castro, Kara Lynch, Lorena Mancillas Corona, Sayak Valencia, and Jennifer Donovan.

Lx Jotx Nostrx (2014), which prompted “the collective creation of spaces to share a playful practice where diversity and dissensions become a party that celebrates the policies and agency of the trans/fag/whore/tortilla/tullidxs”. Members/founders: Sayak Valencia and Katia Sepúlveda.

La Sagrada Familia (2018), a collective/event that conveys performers that address gender issues.

Muxxxe; artistic proposal consisting of actions that include musical and costume production.

These project’s recall is not absolute. However, understanding that the erasure of memory is one of the conditions for the return of ultraconservative ideologies, such as fascism, [5] investigating, storytelling, remembering, become acts of resistance; and these, in turn, allow exhibitions such as MASC4Mascara to be exhibited today within a cultural institution.

—

References

Antonio Bertrán, Damas y adamados: conversaciones con protagonistas de la diversidad sexual (Mexico City: Ediciones B, 2017).

Peter Drucker [coord.]. Arco iris diferentes (Mexico City: Siglo Veintiuno, 2004).

Lx Jotx Nostrx. Statement <https://lxjotxnostrx.wordpress.com/about/> (Recovered on January 18, 2020)

Hito Steyerl, “En caída libre. Un experimento mental sobre la perspectiva vertical” en Condenados de la pantalla (Buenos Aires: Caja Negra Editor, 2014).

Francisco Godoy Vega y Leticia Rojas Miranda, No existe sexo sin racialización (Madrid: Colectivo Ayllú, 2017).

Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, “Rasquachismo: a Chicano sensibility” en Chicano aesthetics: Rasquachismo (Phoenix: MARS, Artistic Movement of Río Salado, 1989).

Andrew Roberts, MASC4mascara. Texto de sala. Tijuana, México, 2019.

Sayak Valencia, «El régimen está (transmitiendo en) vivo» en #Re-visions, no. 9: Madrid, 2019.

Comentarios

No hay comentarios disponibles.