20.05.2019

Questioning mechanisms of epistemic extractivism and depoliticization of Afro-Colombian ancestral knowledge, Claudia Segura talks with Adriana Ciudad about the collaborative artistic process carried out with the Cantoras of Timbiquí, a funeral accompaniment that resignifies the personal battle through the collective.

We Will Meet There, Without Shadow and Without Face is a project by the Peruvian-German artist Adriana Ciudad that unfolds in a myriad of questions and doubts and a multiplicity of symbolic and material devices that urge us to ask ourselves about the representation and integration of information that, either for prejudice, colonialism, or intellectual elitism, has been left out of what we value as knowledge.

It is not inconsequential that this knowledge is usually linked to groups cornered by history, belittled by the academy, and often subjugated at a political-economic level by the countries that harbor them. This piece focuses on an Afro-Colombian community that occupies a very specific part of the Colombian geography, separated by topographical accidents as well as a clear desire to move away from the rest of the state.

These practices unite that which is still a mystery to the prevailing rationality—concepts such as death, the unconscious, trauma, loss, pain, forgiveness, among others. They place existential issues closer to subjective emotions rather than objective reasoning. Hence the profound importance of such practices, for their ontological volatility makes them as vulnerable as they are changing, and therefore difficult to categorize. Approaching such knowledge presupposes a mental openness that not everyone is willing to assume. Adriana Ciudad does it without thinking twice at the moment her artistic practice becomes conscious of the structures of power and knowledge—those of which she herself is part—and releases them to embrace another type of seeing, space to observe, and place to share, where affection becomes the bridge between the strictly personal and the collective.

Claudia Segura: Adriana, tell us, how did you approach the Afro-Colombian community of Timbiquí, and what struck you the most about their tradition of the Alabaos songs?

Adriana Ciudad: When my mother died, the world stopped for me. I did not feel the ground under my feet, I only felt vertigo and pain. “Smash your chest into pieces and break your heart. My soul breaks and I lose my head.” This is described in an Alabao, an Afro-Colombian funeral song.

In full mourning and in the midst of the research on ancestral knowledge that forms part of my artistic work, I coincidentally came across the songs on the internet. Finally, I was hearing verses that spoke of what I was feeling. The melodic force and the intonation of multiple voices singing an alabao in chorus produce an immediate visceral reaction that leads the listener to an emotional catharsis.

It was through sharing intimacy that our collaboration began. We were joined by affection, a collective intimacy. After all, death is universal.

These songs were fundamental to my process of overcoming the death of my mother. I found in them the comfort I was desperately seeking. In Latin-American cities, we are so westernized that we do not usually talk about death: we perform our mourning in solitude and we cry in secret. It is as if there is a collective trauma. Nobody knows how to react or what to say in the face of death. We have unlearned how to share grief, how to experience affection and loss in communion with others. We are determined to think that the intimate is not collective.

My way of approaching the Cantoras [1] of Timbiquí was always personal. When I introduced myself to Nidia Góngora, the lead singer, I told her that I came to her because of the death of my mother, that I was still grieving and that I felt that the knowledge of her funeral practices was a wonderful treasure that I wished to understand more deeply.

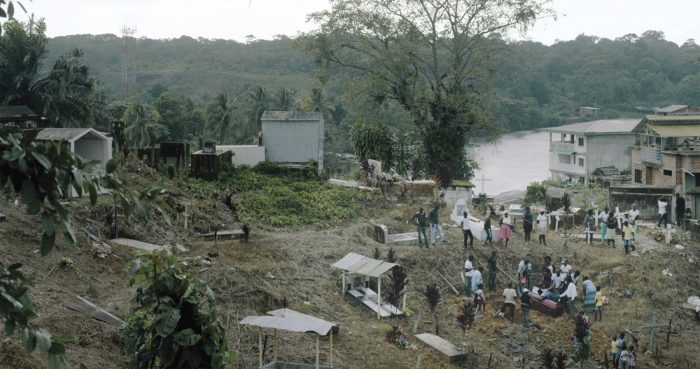

Thus, it was with some skepticism that the Timbiquí Cantoras opened their world to me. In the course of this project, I made two trips to Timbiquí, a remote and almost inaccessible municipality, which can only be accessed by river or plane. It is so complicated to get there that it feels like a journey into a parallel reality. It was there, in the middle of the jungle, that I discovered the healing power of the alabaos of the Cantoras of Timbiquí.

CS: How would you describe the relationship that they have with the state of mind that this song produces, given that it is something almost funereal, which theoretically would be sad and melancholic?

AC: Interestingly, in Timbiquí the atmosphere around death is not only of sadness and melancholy, there is also an atmosphere that resembles a party. Well, if the mourning is well done and there is catharsis, there is a reason to celebrate. As the Cantoras say, “you have to sing to the dead.”

CS: These are communities that have been closed in on themselves by force and have, without a doubt, had to protect themselves. How was your arrival in Timbiquí, since, after all, you were still a foreigner who was invading their spiritual and physical space?

AC: At the beginning of my stay it was not easy to enter into a dialogue with the Cantoras. They were somewhat reluctant to share their knowledge through interviews. “Many vests arrive here. They take out information and never come back,” is what they told me about NGO workers and other entities that go there.

For them, that was me at the beginning of the project: one more vest looking for information. It was only after going through the ritual that they performed for my mother that I won the respect and confidence of the Cantoras. It was through sharing intimacy that our collaboration began. We were joined by affection, a collective intimacy. After all, death is universal.

CS: Tell us, from your personal experience and as a spectator, how do the alabaos operate and what potential do they have?

AC: “The alabaos are sung when there is death,” as they say. You cannot sing just like that. It is believed that “singing without death” will cause someone from the village to suddenly die. During my two stays in Timbiquí, I understood that I had to relate to the alabaos in the same way that the Cantoras do. I had to experience a real and sincere ritual if I wanted to hear and feel the healing power of the alabaos. Once I did this, I understood that they are psychomagic acts. They are performative actions that give us access to healing and to the sacred.

When someone dies in Timbiquí, everybody meets and helps the bereaved settle the practical aspects first—the logistics. Afterwards, the body is veiled at home and kept company with songs for a whole night. The next day the burial takes place. The soul of the deceased person is accompanied by prayers and songs in front of an altar where his photo lies for nine days. For no reason the bereaved family is left alone. The last day is the Remate, which is the final ritual known as Rising Out of the Tomb, in which the soul is helped in its passage beyond. Throughout this process, the people who have suffered the loss—the mourners—go through a very powerful catharsis where crying is welcome, sought, and celebrated by the community.

CS: You returned to Timbiquí after a month to perform the final Remate, which was, without a doubt, the best way to enter into the community—from your fragility and weakness. From then on, you established trust with the Cantoras and you could continue with the project. Right after that healing ceremony, you wrote a text that grew out of your experience.

AC: That’s right. I wrote a poem about what I experienced that night from an artistic point of view. Oliva, along with the help of other Cantoras, set up an altar especially for my mother in the corner of the living room of the house belonging to Popó, Nidia’s brother. We sat in a half moon shape looking at the altar and together, between prayers and songs, we began the ritual of the Remate.

Rising out of the Tomb in Timbiquí

A closure for Remate: our last night to say goodbye, my mother and I.

13 Cantores (11 women and 2 men)

A white altar. Flowers. A photograph of my mother at the center.

It was magical. Moving. Everything vibrated. The songs opened a portal. The altar was the door.

The songs invoked. The space became timeless.

The women transformed into spiritual guardians,

full of calmness, empathy, and love.

Powerful women accompanied by two masculine and sensitive guardians. Tremendous women, tremendous songs.

And suddenly, a butterfly appeared.

Later, the Cantoras told me that before I had noticed,

the butterfly was already circling my crown:

“It fluttered around you, until it landed on the altar.”

The black cloth butterfly contrasted with the white butterfly.

The ritual of songs and prayers became more powerful with the butterfly’s presence…

It is in that moment

that rivers start to flow from my eyes.

Nidia hands me a candle and they all stand. We form a path of two rows facing the altar. The space is filled with light from held candles.

The songs increase their vibration and the butterfly fllutters away from the altar.

The Cantoras become the keys to the portal, they are my protectors and my support.

I fall into a trance.

I feel the first hug my mother gave me at birth, I see her smile,

I feel her enthusiasm for life that always captivated me,

I hear her speak, always eloquent and sharp,

I see her pull giant shells from the sea, I see her dancing without music,

I also see her vulnerability and that which she could not overcome,

but I always feel her loving, dignified and noble,

even when the end of her illness came.

The butterfly flies and flies around me,

until it disappears down the path of women and light.

“Your mother has just broken free from earth.

She is now in the great beyond and in peace,”

Nidia whispers into my ear.

Oliva approaches me smiling, and proudly says:

“I helped you cry, you hear?”

CS: Far from replicating the figure of the artist as ethnographer, I see your practice as one that puts pressure on the difficult concept of complicity and that shows how actions and symbolic devices, that can surpass geography and time, can develop through performative gestures such as sharing. What did you gain from this project as an artist?

AC: For me, this project was an adventure through which I distanced myself from Western methodologies of researching a project, a methodology that is primarily based on theoretical reasoning and hierarchical intellectual classifications. I started from my intuition and the unknown. I understood that the only way to approach this project was to allow myself to be vulnerable, to myself and to those around me. I felt that I had to be brave to face the pain. I discovered that part of the beauty of life lies in its fragility. It is necessary to lose touch with the ground from time to time. For my part, I healed everything that needed healing and along the way, I learned a lot from the wonderful women of the Pacific—of the power of collaboration and of the great voices that exist in the most remote places of South America.

Cantoras is how women chanters of the alabaos are known as.

Comments

There are no coments available.