A reflection across the work of Cecilia Vicuña on the meaning of being indigenous and the questioning of the colonialist gaze that has conditioned the relationship with our natural and race roots.

“In the Andes they say: Time has come to renew the past. Future remains behind: It has yet to arrive.”

Andean proverb

From the time I first met Cecilia Vicuña (b. Chile, 1948), I was awakened to a deep curiosity about the Andean indigenous universe that has for millennia inhabited the geographical region where I grew up, central Chile’s Aconcagua Valley. Her work began, coincidentally, in the year 1966, at the mouth of the Aconcagua River, in Concón. Back then I wasn’t even born, but it was in my first conversations with Vicuña that I began recognize myself in those places to which she’d paid homage over more than fifty years of artistic evolution, in the form of a life dedicated to listening to the voices of Chile’s ancient peoples.

As I get deeper and deeper into her work, and as I see my own consciousness expand, the more I am able to relate to my own land. I wonder what it means to be indigenous: Must you have indigenous blood to share in its worldview? Or—more than ever today—is being indigenous a consciousness? Every day in the news, we see a scenario in which global warming is increasingly real. But indigenous nations, thanks to their deep understanding of the union between nature and the human, provide a global example of care and respect for the environment. It’s encouraging to see how in the last fifteen years—despite being violently harassed by corporations and multinationals—it has been indigenous activists who have created a way forward, preventing even greater environmental disaster through natural-resources stewardship planning, ancient knowledge and, above all, by defending their territories.

With the advent of the colonial period, a central characteristic of the South American indigenous worldview was lost, effaced through Christian evangelization and the introduction of new thought systems. As pagan animism was destroyed, Christianity made the exploitation of nature possible amid a climate of utter indifference to the feelings of natural objects.[1] Cecilia Vicuña’s work is situated at the heart of that struggle, where, as the artist herself has stated, “consciousness is human beings’ greatest art, where the physical act of producing performances, shows, and objects is merely the tangible manifestation of our consciousness, that seeks to touch on other forms of consciousness,” and paves the way for an understanding that once again makes us feel at one with nature—a fundamental knot in the thread of life.[2]

The nullification of this model of indigenous thought has spread to other spheres of knowledge to the point of convincing us that everything linked to the indigenous world was primitive and backward. This goes entirely hand-in-hand with the invisibility to which Cecilia Vicuña’s work has until very recently been subject in the contemporary art scene, since a nullification of the indigenous contribution to the history of the Western Hemisphere is based on a nullification of the majority of the sources from which Vicuña’s artworks are nourished. Thus exhibitions such as About to Happen, her first large-scale show in the United States and currently on view at the New Orleans Contemporary Arts Center, as well as her participation in Documenta 14, take on major significance with regard to the near future. As the About to Happen curatorial text points out, Vicuña’s work reframes de-materialization as something beyond a formal outcome of 1960s-era conceptualism—as it is commonly understood—as well as a formal consequence of radical climate change, and in both cases as a process that molds public memory and responsibility.[3] Lucy Lippard, who has followed Vicuña’s work very closely, writes in 2014 that Vicuña and her partner, poet James O’Hern, created a video to recuperate this collective memory and environmental responsibility by means of oral tradition.[4] Entitled We Are All Indigenous, Vicuña added to the human family but we have forgotten it. This can be a problematic notion, Lippard asserts, in a scenario like that of the United States, where having indigenous forebears has taken on an exotic vogue. That said, the intent behind Vicuña and O’Hern’s declaration is to once again take up the indigenous thought model in order to drive the emergence of a global consciousness that can prevent environmental catastrophe. Far from being an appropriation of a thought-system or an identity, it is an urgent wake-up call.

I’ve often heard people say Cecilia Vicuña appropriates elements from the indigenous world as a way to exoticize her art; I’ve even heard— in written texts—that Vicuña thinks she’s an Indian. But what ethic would impede an artist from developing indigenous-realm concepts and beliefs as a means of eliciting consciousness within us, the viewers, that could lead us to prevent global disaster? I also wonder who else could attest to the enormous crimes colonists committed when they forbade the indigenous to continue using their own names, speak their languages, and believe in their gods. I have witnessed the respect with which Vicuña approaches every place, even to pick up an apparently insignificant pile of twigs, stones, and small shells; the care she takes when she introduces herself to others; and even the way she alters her voice in presentations, so that the atmosphere she creates, rather than what she says, is what matters. Vicuña speaks constantly of listening. Her poetry, installations, and performances are not born of her intellect; rather, they are a message that reaches her in an almost medium-like fashion, via a highly archaic means of communication. Testimonies abound from people who have attended her performances or readings, and they bear witness to the trance Vicuña embodies as well as the way she transmits numerous dimensional intersections that exist in the timeframe we call the present. Vicuña’s work is future work nourished by voices of the past, or, as the artist says, ancient thoughts. Her Palabrarmás are poems where words come to life; no written phrases in the book can ever be read in the same way again. They change, they mix with new stories, they translate to other languages, and they expand or contract in sounds only Vicuña’s voice can emit.

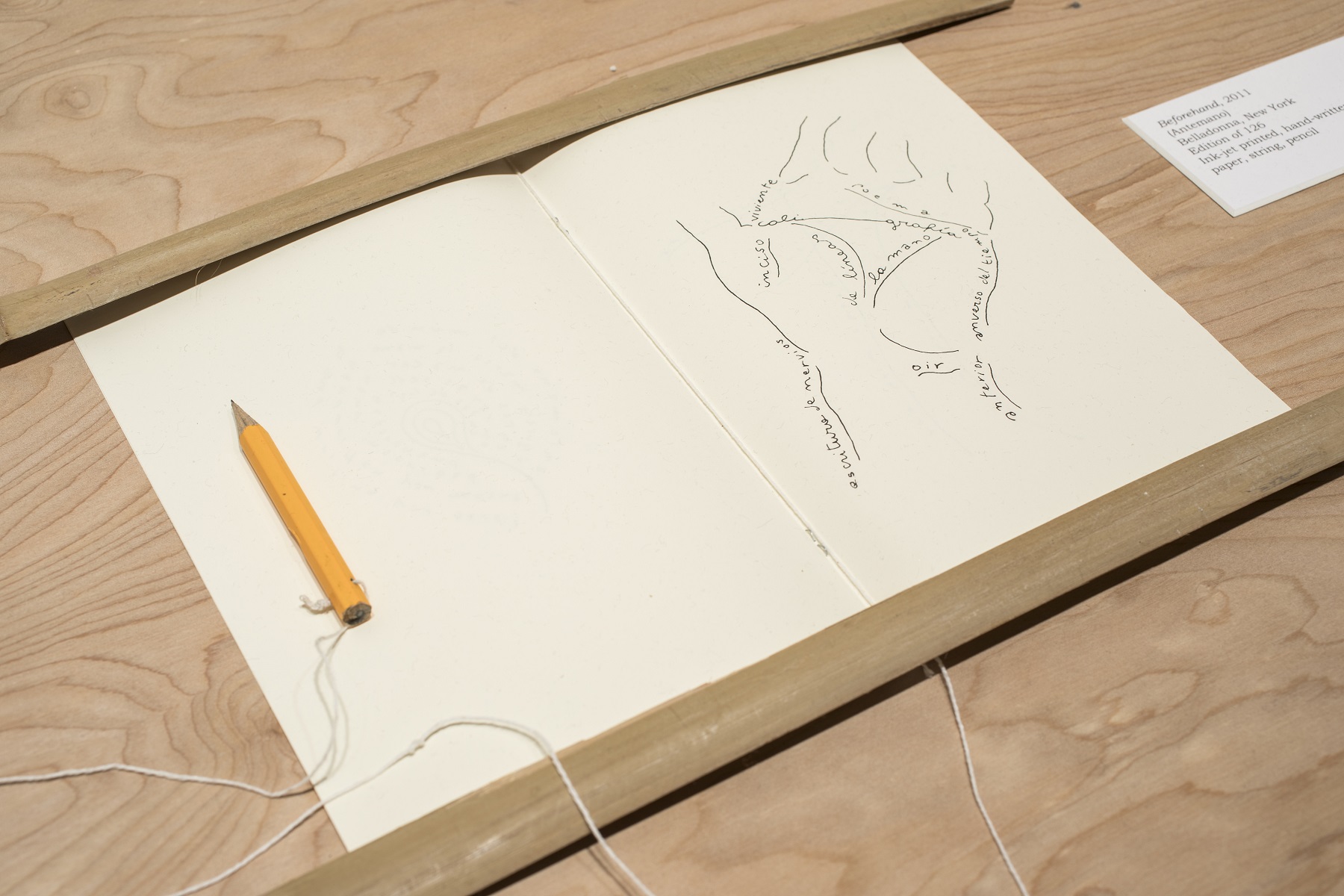

It’s no surprise that when we look at Vicuña’s various installations, we find ourselves before the same elements time and again, as if through constant repetition, those materials—found or elaborated in their urban environment and/or regenerate life, oxygenating our blood as in a deep, purifying meditation that lets us connected to other sources of knowledge. Materials such as wool, bamboo shoots, rubble, branches, fishing line, ropes, nets, and feathers are always there on the table in her studio, as are books that she herself has made, or that she studies on the widest array of subjects. Plus there are words—lots of words scrawled onto scraps of paper. As About to Happen co-curator Andrea Andersson cogently surmises, “each new artwork is a record of a previous work or action as part of a long practice of perpetual revision,” a constant split between doing and un-doing.[5]

At the heart of her practice, there are two concepts to which her work is dedicated, both equally important: the knotted Inca weavings known as quipus, and the precarios. Both lend great value to water as a source of life. Decades earlier, Cecilia Vicuña discovered that in the time of the Incas, tactile quipus were woven from knotted cords as a means of keeping accounts. She also learned of what was called the ceque, a virtual system of forty-one imaginary lines starting out from Cuzco and extending toward the four corners of the world. The quipu and the ceque connected all communities to a totality, creating a vision of the common as something alive. A collective fabric oriented toward mountain water sources. It speaks to us of water’s tremendous importance in the Andean worldview, protecting millennia-old springs, glaciers and additionally, the places where fresh and salt water meet. As curator Dieter Roelstraete points out, it’s possible the monumental quipu Vicuña presented at Documenta 14, made of strands of red, un-carded wool, connects the mother goddess of the Andes with the maritime mythologies of Ancient Greece.[6] Underlining climate change’s global scale and the planet-wide need to create a collective call for life-force, Vicuña brings a ritual practiced for years in other waters, that are in fact the same, to the Mediterranean.

With regard to the precarios, Cecilia created the name Arte Precario as an independent, autonomous category for her work in the mid 60’s. While not from the Andean realm, it does have an immense poetic force that clearly permeates all existence, in every direction. Her Precarios are small-scale sculptures made from discarded objects that are at once fragile and grandiose. They are portraits of life’s precariousness, of the ephemeral, the transitory, and the transcendent. While the first Precarios were created in the 1960s and installed at the shore in Concón, to be washed out to sea, they should be seen as a work in progress from which the concept that gives them their name emerges. Just as Vicuña’s participation at Documenta 14 is dedicated to The Story of the Red Thread,[7] About to Happen is dedicated to the discarded, whether this may be people, objects, or stories. For that reason, the exhibition includes a large gallery filled with small-scale Precarios as well as a monumental structure created by a collective gathering of materials from the coast of Louisiana that resembles a raft, or rather a structure that might stay afloat for a minute or two and then dissolve into the current. Dissolution is also an element that moves through Vicuña’s artistic practice, specifically one’s un-making in order to unify with some other whole.

What happens when the future is not something out there, but rather, something that comes from the past, from listening to our ancestors or from the force of archaic world-visions?

There are different ways to be indigenous. Cecilia Vicuña embodies the strength of her Diaguita-nation forebears from the north of Chile, as well as that of her Basque-Irish origins and that of her Spanish family that reached Chile in the seventeenth century, perhaps the start of her mixed-race heritage. Maybe that strikes those who feel indigenous thought can only be transmitted by blood as pertinent, but returning to one of my initial questions, what does it mean to be indigenous? At Cecilia Vicuña’s performances—and even just listening to one of her improvised songs in some corner of Chile’s central valley—I’ve been able to hear my ancient thoughts, the voices of those who’ve occupied these lands for thousands of years, that still live in me and in all of us.

Comments

There are no coments available.