30.11.2015

The curatorial field cannot be discussed without acknowledging its interdependence with the transformations that have occurred in artistic practice and in the world of institutions over the past 60 years. There is a vast international bibliography on this subject in the Global North, but very frequently it isolates the emergence of curating from its broader context. However, the main problem is that the view from Europe and the United States builds up a narrative starting from local examples in hegemonic countries (such as the inaugural myth of Harald Szeeman in When Attitudes Become Forms, 1969), ignoring the fact that similar changes have taken shape in countries of the so-called Global South. The climate of experimentation and rupture that so well characterizes the art of the 20th century was present in cities such as Buenos Aires, Mexico, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo, just to mention those in Latin America. This text will concentrate on the case of Brazil and address the connection between the rise of a generation of experimental artists that emerged in the late 1960s and the consolidation of the first generation of Brazilian curators (at a time when they were not yet called so), in the context of the most brutal period of the military regime. More specifically, it will examine the role played by the art historian Walter Zanini in building up a dynamic museum of contemporary art at the University of São Paulo, as well as his research and support of mail art and video art.

In the 1960s, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo already had a number of relatively established art institutions. The Museums of Modern Art of Rio and São Paulo, the MASP and the São Paulo Biennial had already been in place for over a decade and had been promoting the exchange of ideas and the circulation of international artists, bringing the Brazilian art world up to date with what was happening in other parts of the world. Mario Pedrosa, the main Brazilian critic of the 20th century moved in international circles and, in 1959, had organized the International Congress of Art Critics in Brazil. Pedrosa had been the mentor of the artists who created the Neo-concrete Movement, and was an important supporter of Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark, and Lygia Pape, to name the most well-known. When Oiticica, Clark, and Pape began to raise the question of public interaction and their work also moved beyond traditional artistic codes, Mario Pedrosa realized that this marked the beginning of postmodern art (2) and understood that he could not accompany artists in this new stage in the history of art. At that time, a new generation of critics started a close dialogue not only with the neoconcretist generation, but also with the younger artists who would become known as “the barricades generation” (3).

These critics not only understood the new artistic vocabulary that was being developed at the time, but also came to question the way it was presented. A clear example from Mario Pedrosa’s hometown of Rio de Janeiro is Frederico Morais, a young critic from Minas Gerais who could be regarded as the first independent curator in Brazil. In July 1968, he organized the Arte Pública no Flamengo event, in which artists produced their works in front of the audience in a climate of interaction and exchange. Two years later, Morais promoted the Do Corpo a Terra exhibition in Belo Horizonte. Twenty-five artists were invited to stage interventions in the city to commemorate the opening of the Palácio das Artes.

In São Paulo, with the growth and consolidation of the art biennial, its mastermind, the impresario Francisco Matarazzo decided to close down the Museum of Modern Art – the institution that until then had been responsible for organizing the event, in order to dedicate himself exclusively to the biennial. As the MAM-SP’s (Museum of Modern Art) collection was practically the entrepreneur’s private collection, he brought it to the University of São Paulo and created the USP Museum of Contemporary Art. There was great expectation in the art world that the director would continue to be Mario Pedrosa (the last to direct the MAM), but the university stipulated that the post be filled by someone with a formal employment contract. They therefore appointed art history professor Walter Zanini, who had recently returned from France and had a solid academic training under the historian André Chastel. In 1963, the MAC – USP (Museum of Contemporary Art at University of São Paulo) first opened its doors. From the outset, Zanini questioned the role of the museum in the contemporary world and its function in relation to the art of its time. The fact that the MAC was located inside a university reinforced its educational character, but the director took this peculiarity as an invitation to experiment and provide new readings. With a highly important collection of work by modernist artists, the MAC combined the functions of reviewing history (with retrospective shows of artists who had still not been the subject of monographic exhibitions) and projecting the future (by organizing shows of the work of emerging artists). At first, emerging art was presented in the museum in the Jovem Gravura Nacional and the Jovem Desenho Nacional exhibitions. This was the case up until 1967 when the Jovem Arte Contemporânea (JAC) project began, opening the way for research in all sort of media and with a strong emphasis on experimentation.

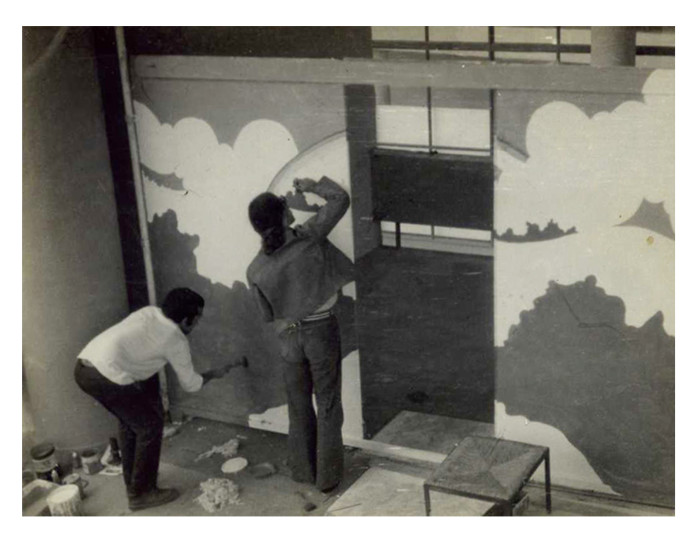

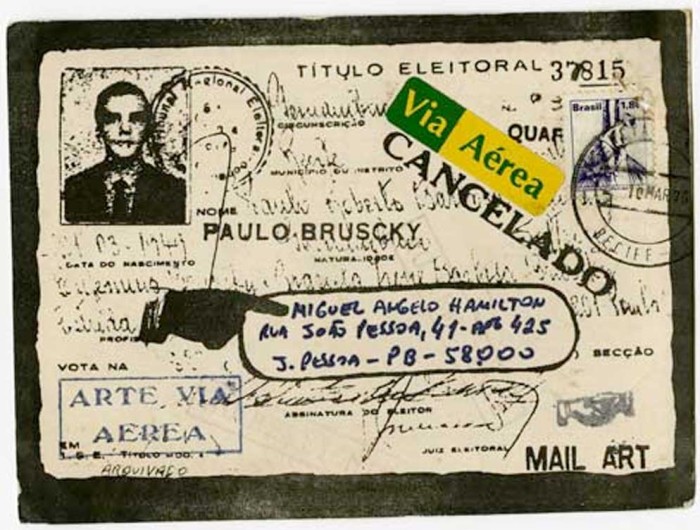

In the 1970s, Walter Zanini’s interest in video and mail art grew. Without ever stopping to teach art history at USP, he broadened his knowledge of the most recent developments in art related to communications and networks. Working as part of a network had always been an important part of Zanini’s museum management ethos and this may have influenced his enthusiasm for the power of connection, decentralization and the mail art network, and also of the enormous challenges and confrontation of naturalized values that this movement brought to the art world. A founding member of what would become CIMAM (the ICOM International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art) and founder of the Brazilian Art History Committee, the director of the MAC – USP was a great enthusiast for sharing with peers and especially with artists. It was through listening to artists that Walter Zanini came to change the selection criteria for JAC in 1972, which would turn into the most daring edition of the project. Instead of portfolios submitted to a selection commission, the artists who would participate in the 1972 edition were chosen by lot. The museum space was divided into sections of roughly equal size and the selected artists had a week to produce their work in the indicated space; some artists swapped or even sold their spaces. The model received much criticism and great praise in equal measure. For some, the relinquishment of critical standards for the artist selection was an act of inane populism. And for others, it was a grand experimental gesture and an act of curatorially daring model. It was certainly the only time when the participation of artists was left to chance. But experimentation continued to guide the actions of the MAC- USP.

Looking into promoting video art in São Paulo, Walter Zanini managed to acquire video equipment for the museum in 1974, since the exorbitant prices of the Portapak had put it out of reach of artists themselves. In Rio de Janeiro, a group of artists led by Anna Bella Geiger got their hands on a set of filming equipment that enabled them to produce the first crop of Brazilian video art –an achievement that received great praise from Zanini. The curator provided unrestricted support for experimentation with different media and systems of circulation. It was no coincidence that the main institutional link that the MAC – USP established under the 15 years of Zanini’s administration was with the Buenos Aires CAyC (Center for Art and Communication). There was a great affinity between Jorge Glusberg’s project and that of Walter Zanini in terms of the exploration of a new transgressive form of art based on systems of codes and signs. However, we should bear in mind the different characters of the CAyC and the MAC – USP. While the former was an independent space without a collection, the latter followed all the precepts and protocols of a museum institution. It could be argued that Zanini’s MAC – USP was one of the most daring museums in South America in the 1960s and ‘70s. The art historian’s classical training makes his openness to a technological avant-garde even greater.

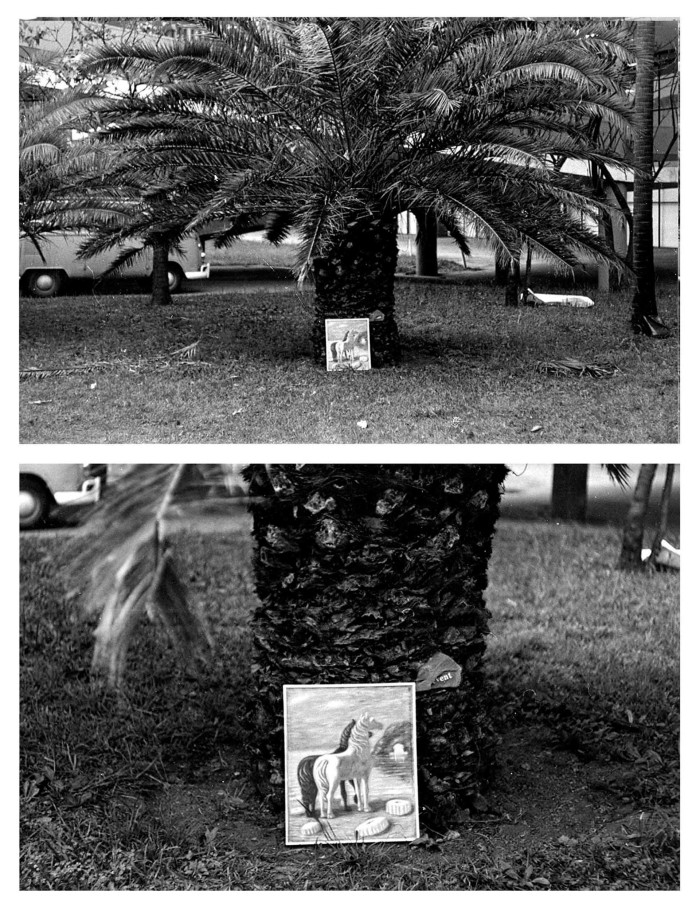

Zanini maintained an open and frank dialogue with the young artists of the time, as exemplified by the actions of Genilson Soares and Francisco Iñarra’s (1947-2009) Arte/Ação group, whose modus operandi involved the appropriation of the work of other artists and its installation in institutional spaces as a way of criticizing them from within. The relationship between Zanini and the group was so close that they and other São Paulo artists actually had the keys to the main door of the museum (although this has been denied by some). In 1975, Soares and Iñarra arrived early in the morning at the MAC – USP and removed the Event stone, which was a part of the Impresso sobre Rocha installation by Japanese artist Chihiro Shimotani, and carried it around the museum. The whole action was documented in photographs and turned into a piece called Evento com a pedra Event. The museum’s director was highly supportive and he even sent this documentation to various exhibitions. According to Genilson Soares, Zanini said, “At least you didn’t take out a painting!” The curator’s remark provided the idea for a new piece, this time involving Giorgio de Chirico’s Horses on the Seashore. On the one hand, these actions demonstrated the great institutional fragility of the MAC – USP, but also Walter Zanini’s great openness to the most transgressive, exploratory, and experimental artistic proposals.

How was it possible for a museum under the yoke of the Brazilian military dictatorship to be an open platform that tested limits? Unlike cinema, music, and theater, the visual arts have never enjoyed great popularity in Brazil and have always been held to be an art form produced by the elites for the elites. The attention of censorship fell more on other media. However, visual arts were not left untouched by censorship and persecution. Art exhibitions and biennials were shut down or had works removed by the military regime, as was the case with the 2nd Bahia Art Biennial in 1968. Interestingly, the MAC – USP was not harassed by the regime. Some researchers believe that the activities of the MAC – USP were not taken very seriously, precisely because they supported and collected the work of very young, not yet institutionally legitimized artists. It would seem that the museum’s extreme experimentalism freed it from the constraints of the military regime.

This is just one fragment of a great web of interconnections that enabled the artistic vocabulary in Brazil to be renewed, bringing about a shift from an ecology of modern art revolving around the art critic towards the ecology of contemporary art where the role of the curator as we know it today emerged. Such changes have occurred around the world in various specific contexts. The aim here is not to decide who came first, but merely to point to the vast constellation of different players and situations that helped to build the porous and flexible fabric of contemporary exploration in the field of art.

Notes:

(1) This text is a highly abridged version of one chapter of my doctoral thesis Aracy Amaral, Frederico Morais and Walter Zanini – the genesis of the curatorial field in Brazil for the UFPE’s Postgraduate Program in Sociology, to be defended in the first semester of 2016.

(2) “Arte Ambiental, Arte Pós-moderna, Helio Oiticica” published in Correio da Manhã, 26 June 1966.

(3) Artur Barrio, Cildo Meireles and Antonio Manuel are some of the artists belonging to this generation.

Comments

There are no coments available.