13.04.2015

The Witch’s Cradle is a 16mm film by avant-garde filmmaker Maya Deren in collaboration with Marcel Duchamp, that was filmed in 1943 in Peggy Guggenheim’s gallery Art of This Century in New York. This essay examines how the film’s narratives become triggers for sensory exploration between the actress and her surroundings, and speculates on the mystery around the unfinished film, the artist’s collaboration, and the relationship between the actors and the architectural space of Art of This Century.

Maya Deren, Witch’s Cradle, 1943

Maya Deren, Witch’s Cradle, 1943

The phrase “the end is the beginning is the end…”, written around a pentagram and impressed on the actress Pajorita Matta’s forehead — as it appears in the 16mm film The Witch’s Cradle (1943) — can be read infinitely. The silent, unfinished, twelve-minute film is a collaboration between Ukrainian filmmaker Maya Deren and French artist Marcel Duchamp and was set at Peggy Guggenheim’s New York gallery Art of This Century, designed by the Austrian architect, artist, and designer Frederick John Kiesler. Its title, The Witch’s Cradle, references the witch-hunts that took place between the 15th and 18th centuries in Europe, when inquisitors would use punishment and force indicted witches into a sac that they then hung from a tree’s branch and swung intensely. When word about this new form of punishment spread the witches themselves started to experiment with the method, and found that the sensory deprivation and mix up induced by the experience caused hallucinations. The first time I saw the film, I associated the strings that Matta’s character seems to be conjuring, pulling, and winding, with symbols for such punishment. Although, perhaps, they just embody Duchamp’s obsession with knots.

Deren’s interests in voodoo and altered states of consciousness are fundamental elements for the film’s rhetoric and bestow in it an ambience of the surreal. During the film’s twelve-minute run, only two actors appear: Matta and Duchamp. Matta personifies a virginal looking girl, dressed in white and walking barefoot around the gallery. Her character, which possibly represents a witch, is physically seeking an altered state of consciousness by drifting through the darkened space at night. Her movements evoke psychedelia; they do not follow a precise choreography and as such, suggest her passage into a trance.

What signals indicate a passage into a state of trance? For both the body and mind to enter into a state of unconsciousness? Are they uncontrollable body movements like profound physical contortions, eyes rolled back, and sometimes,the articulation of unknown words? In scientific terms, the trance is defined as a psychopathological phenomenon. But can our environment and surroundings also influence us into a trance or a state of actual possession?

However, the goal of this text is not to enter into Deren’s cinematographic language through the rituals of voodoo. Instead, I’m interested in exploring the relationship between the architectural space of the gallery and the use of props and artworks as vehicles to spur certain senses of the psyche: let’s call it a psychogeographic exploration.

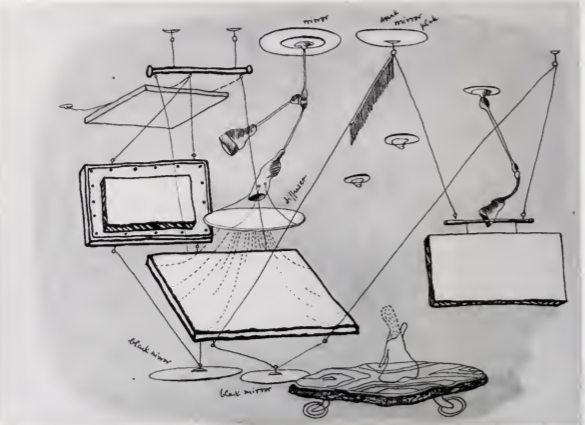

Conceptual drawing for lighting system, Art of This Century, New York, 1942. Ink on paper, 8×1.1 inches (20.3×27.9cm). Kiesler Estate.

Conceptual drawing for lighting system, Art of This Century, New York, 1942. Ink on paper, 8×1.1 inches (20.3×27.9cm). Kiesler Estate.

1. The gallery as a cave

The film’s setting plays an essential role throughout its course, we could even say that it becomes a character in itself. The Surrealist gallery, Art of This Century was an experiment for Kiesler: the architect and artist sought to activate the senses, including perception, by converting the gallery into a kinetic and dynamic stage where the spectator could transform into a personage or another art piece.

When Peggy Guggenheim commissioned Kiesler to do the project, she demanded one thing: all the paintings should be exhibited without frames, an aesthetic that the artist had already established before (1). Taking into consideration Guggenheim’s petition, Kiesler designed wooden curved walls that resembled cave walls when installed in the gallery. Kiesler’s design sketches show how his visualization techniques were influenced by his own interpretations of the primitive man’s experiences. As he noted in his Notes on Designing the Gallery (1942):

“The primitive man did not know vision and fact as separated worlds. When he carved and painted the walls of his caves or the sides of a rock, there were no frames or cut edges between his artworks and the space of life.” (2)

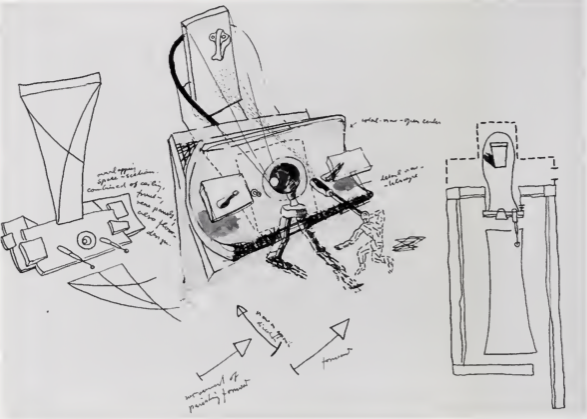

Telescope view of street from gallery, Art of This Century, New York, 1942. Ink and gouache on paper, Kiesler Estate.

Telescope view of street from gallery, Art of This Century, New York, 1942. Ink and gouache on paper, Kiesler Estate.

Using string as support, Kiesler suspended the pictures from the roof in which he set a device with biomorphic forms and modular functions. He also generated a visual and aural environment in which the gallery lights went off in intervals, suddenly and without notice, to be replaced with the sound of a marching train.

Art of This Century became the optimal stage for Deren — a place suspended in time and space where art pieces became signs, or in her own words, “cabalistic symbols of the twentieth century.” The objects present in the gallery become part of Matta’s choreography, they endow the stylization of her gestures and confer a ritualistic dimension to functional movement. She interacts with the artworks in some of the scenes. She entangles the strings in her hands, uses a self-sustaining pendulum to hypnotize herself, and switches on Kiesler’s Vision Machine which was originally designed to examine sixty-nine of Duchamp’s reproductions of his piece, Boîte-en-valise. Produced over fifteen years (1930-1945), these reproductions were exhibited and transported as a portable museum, inside a suitcase which Duchamp carried from one place to the next. The artist considered these reproductions and their moving system as institutional critique questioning originality, and the ways museums circulate images. This leads me to reflect on a possible connection between The Witch’s Cradle and Duchamp’s reproductions: a place where smuggling and infiltration of a portable museum into the gallery by the artist become an event that exists between the shadows and the prohibited. And in Deren’s film, filming Matta summoning a ritual inside of the gallery space at night during closed public hours conjures speculations of rites as prohibited acts.

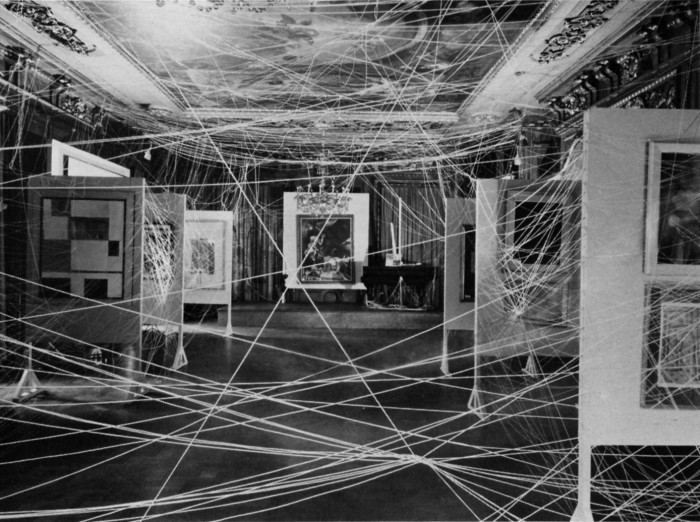

One Mile of String, (First Papers of Surrealism Exhibition, NY), Marcel Duchamp curator, 1942, Surrealism.

One Mile of String, (First Papers of Surrealism Exhibition, NY), Marcel Duchamp curator, 1942, Surrealism.

2. Treasure hunt with Duchamp

Duchamp shows up in the movie only momentarily, as a sort of ghost: a string threading around him like a snake ascending up a tree, and which Matta and Duchamp wind around their fingers to make a spider web form. The following scene shows the string, again moving as an animate being, going up Duchamp’s back and finally wrapping itself around his neck. Building on the film’s mysterious aura, this sequence only shows the artist as a silhouette giving his back to the camera, never looking at it (is Duchamp hiding something from someone?), which made me wonder: what is the relationship between the string and the artist? Also, what is the relationship between the string and the rite?

This appearance of Duchamp, who was probably playing himself in the film, makes us speculate about the string as an allusion to, or a direct extension of the threads he had used before in his 1942 exhibition, First Papers of Surrealism; in it the threads seemed to trap the exhibited pieces as if in a spider web. First Papers of Surrealism actually reveals a lesser known aspect of Duchamp’s practice as a curator which has caught historians’ and curators’ attentions as a more obscure typology of exhibitions: the artist as curator (3). Or, maybe the string is a metaphor for the pieces of his life and work. Or, perhaps, as art historian Paola Magi suggests in her book, Treasure Hunt with Marcel Duchamp, the life and work of the artist may be interpreted as a series of enigmas and hidden signs. For example, in the scene in which the string comes to life and climbs up his neck, the artist might be interpreting his own death by choking himself. Or, like Magi suggests, the string could represent two things: that the artist is the work of art or that the artist’s life is the work of art (4).

Surrealist gallery, Art of This Century, New York, 1942.

Surrealist gallery, Art of This Century, New York, 1942.

3. Inconclusive friendships, unfinished projects

I look for The Witch’s Cradle on YouTube or in the corny, cult webpage where I first found out about it, and I watch it again and again. Each time I’m finished watching, I come back to the same questions: why didn’t the artists ever finish the film? Or was it always their intention that the film remain inconclusive?

Certainly, this collaboration between Duchamp, Deren, and Kiesler is not a coincidence. There are specific events that unite these three characters. Below I list some facts or thoughts that can serve as starting points to try to understand the bonds that resulted in The Witch’s Cradle, and why it remained inconclusive:

1/ Kiesler and Duchamp met in Paris during the mid 1920s and maintained a friendship until the 1950s. During twenty-five years they collaborated on different projects (publications, machines, and exhibitions, among others), and engaged with similar themes, like perception and mechanisms of vision, in their respective practices. They shared the same group of friends in Paris and intellectual circles in New York.

2/ The First Papers of Surrealism exhibition could well have been the first time both artists met Deren. The filmmaker had been part of the Surrealist group in Europe. On the other hand, neither Kiesler nor Duchamp considered themselves part of any group (and much less of the Surrealist group). Still, like many of the Surrealists, the three found refuge in the United States by the beginning of World War II.

3/ Deren embarked upon a long investigation of Haitian voodoo which is explained in her book, Divine Horsemen: The Voodoo Gods of Haiti (1953). She was the first white woman to become a high priestess of the Haitian religion. For her, the Surrealist movement served as the platform that brought her to voodoo: “as a form of expression, because through it was able to reach maturity by means of the inner journey into the mind.” (5)

Throughout his life Duchamp worked with many other artists on collaborations, most of which remained unfinished. Deren’s film is on this list. Actually, Deren was known for leaving a number of other projects unfinished: films, texts, screenplays, etc. In fact, at some point in her career she promoted her films as “Abandoned Films”; for her, this act of leaving projects open is tied to an aesthetic which refuses to close circles. There is no element in The Witch’s Cradle which points to a denouement, nor one that augurs that the film is about to end. Rather, from one moment to another, without any explanation, the film just ends.

Maya Deren, Witch’s Cradle, 1943

Maya Deren, Witch’s Cradle, 1943

As I mentioned before, Duchamp and Kiesler ended their twenty-five year relationship in the 1950s, but the reason remains uncertain: maybe one said something that offended the other, or one stole an idea from the other, or insulted him with a piece, or a text… or, what could have been the motive? On the other hand, Deren and Duchamp’s relationship is still an ambiguous episode within art history, which has given space for speculations about their collaboration. Did they meet while having coffee in some apartment at Greenwich Village? Did a common friend introduce them? Or in any case, did they keep in touch after collaborating on The Witch’s Cradle?

The act of leaving a part of his or her oeuvre inconclusive is tied to a notion of the artist as someone constantly looking for reinterpretations of him/her self. This process forms part of his/her own identity and discourse.

I can mention some artists for whom self-reinterpretation has become an intrinsic part of their persona: Beuys, Lee Byars, Jonas among others. But undoubtedly, the person I think about the most concerning this notion of the inconclusive and of the metaphysic transformation of the self, is experimental theater director Jerzy Grotowski. Grotowski abandoned theater to create a system of movements and spatial practices combining anthropology, nature, and rituals, which made him one of the most important contributors of contemporary performance. With the sudden shift from Paratheater to the Theatre of Sources in the late 1970s, Grotowski expressed an interest in the transcultural rituals and shamanistic practices like voodoo in Haiti, practices from Huicholes in Mexico, and yoguis in India.

Grotowski carefully cultivated his mysterious character. He dominated a metamorphic personae; he disappeared and reappeared, disemboweling diversity in his theatrical practice. With each new phase, the Polish theater director also altered his physical appearance. By the late 1960s, Grotowski left Poland and moved to America. At the time, he had short hair, a clean shaven face, wore sunglasses and an omnipresent dark suit. His travels in the States and contact with 1970s youth subcultures had a profound influence and a significant transformation on his appearance. He started growing out his hair and beard, wore jeans, and underwent drastic weight loss As Richard Schecner, one of Grotowski’s disciples, said about his constant changes: “It is unusual that a person can have so many aspects, so many faces, so many presences, so many characters.” (6)

And so, the following questions emerge: can we assume that Duchamp and Deren are artists who over-curate their persona as part of their artistic discourse? What is the motive for their inconclusive collaboration? This film was part of something bigger, a preconceived plan which contributes to the mysticism surrounding the same film and collaboration. Was it on purpose?

I will end this text with a Paul Valéry quote which Deren supposedly used to refer to unprecedented events, these trivial events which live between the visible and the invisible, these inconclusive events: “a poem is never finished, only abandoned.”

Rodrigo Ortiz-Monasterio

Notes

(1) Lisa Phillips, Frederick Kiesler, editor. New York Whitney Museum of American Art Catalogue. New York, Whitney Museum Publications, 1989, p. 63.

(2) Kiesler, Selected Writings, from “Note on Designing the Gallery.”, 1997. Hatje Cantz Verlag GmbH & Co KG, Berlin.

(3) Elena Filipovic: A museum That is Not (2009). http://www.e-flux.com/journal/a-museum-that-is-not/

(4) Paola Magi, Treasure Hunt with Marcel Duchamp, Edizioni Archivio Dedalus, 2011, Roma.

(5) Ally Acker, Reel women. Pioneers of cinema. 1896 to the present, New York, Continuum,1991, 96.

(6) Richard Schechner, “Exoduction: Shape-Shifter, Shaman, Trickster, Artist, Adept, Director, Leader, Grotowski” en The Grotowski Sourcebook, Richard Schechner and Lisa Wolford (eds.). Londres: Routledge, 1997. 461-2.

Comments

There are no coments available.