14.09.2015

Shock and Alejandro Jodorowsky are synonymous. Those familiar with his films since the 1966 production Fando y Lis have come to expect this element in his works. But when and where did this aesthetic of shock originate? His Panic Theory -developed in the early 1960s- and its first visual expressions, the “panic ephemerals,” hold the keys.

The artist, director and writer Alejandro Jodorowsky is best known for his shocking and controversial film career that spans nearly six decades. During the 1960s, he began to develop a distinctive aesthetic vocabulary, consistently employing disturbing and jolting imagery that was frequently the target of censorship. His cult-favorite films such as the acid-Western El Topo (1970) or his epically delirious The Holy Mountain (1973), feature explicit depictions of nudity, sexuality, physical violence (particularly against women), animal sacrifice, and anti-religious and anti-authoritarian sentiment, mixed with a bit of alchemy and magic. An aesthetic of shock permeates his body of work and he has applied this concept not only to his films, but also his theatrical productions, writing, performative interventions, television shows, and even in comics, as recent exhibitions such as the retrospective at CAPC Musée d’art contemporain in Bordeaux, curated by María Inés Rodríguez, have helped to elaborate and contextualize. But how and why did Jodorowsky arrive at this aesthetic of shock and how might we problematize his reliance on this strategy? In order to assess this, an investigation into his Panic theory and his “panic ephemerals” is necessary.

Arriving in Mexico after a stint in Paris, Jodorowsky stayed in regular contact with fellow artists in Europe including Fernando Arrabal and Roland Topor. All three artist-writers worked in a Surrealist mode but grew frustrated with the movement, comprised, as has Jodorowsky described, by “men in ties that talked about politics and not art, they were bureaucrats.”(1) In his estimation, the Surrealists saw the movement as a culture, but one that had grown increasingly rigid and regulated under the guidance of figures like André Breton. In response to these conflicts the artist began to develop a theory of Panic.

In Mexico, Jodorowsky began to develop his world of panic, engaging what little experimental theater scene the country had to offer. He staged productions of Samuel Beckett (Theater of the Absurd) and Antonin Artaud (Theater of Cruelty), both of whom informed his drive toward panic and particularly the latter for his introduction of the irrationality and instability into the equation. These early productions, pointed towards a desire to violate the assumed roles and spaces of traditional theater productions. Additionally, they were demonstrative of his desire to eliminate ties to the bourgeoisie and attempt “to place the audience on the verge of crisis.”(2) Panic theory proposed that through the creation of an environment of forced panic and chaos, the audience might reach a state of euphoria and transform, thereby turning into the “panic man” who is free from the constraints of social, historical, and political repression and the chains of “individual thought”.(3)

In addition to theatrical concerns, Panic theory also developed as a possible escape or solution to the crisis over the “real” (particularly the debate over figuration and abstraction) that permeated international artistic debates of the time.(4) Given Jodorowsky’s theatrical roots, it is unsurprising that he turned to ephemeral performance as a means of critiquing and challenging artistic categories and the interdependency of art and institution at the time.

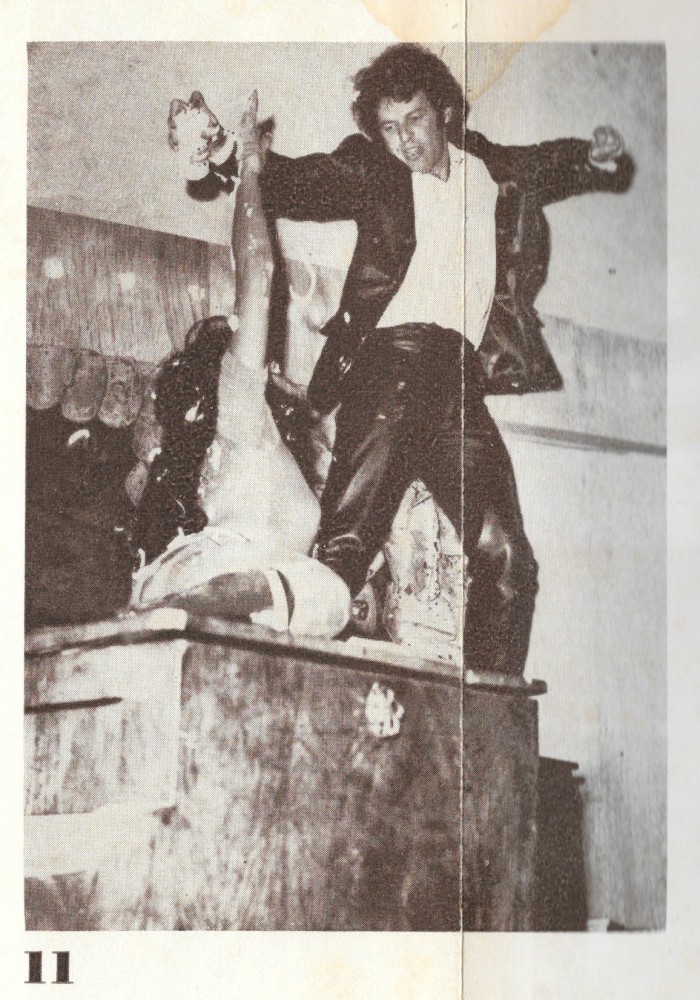

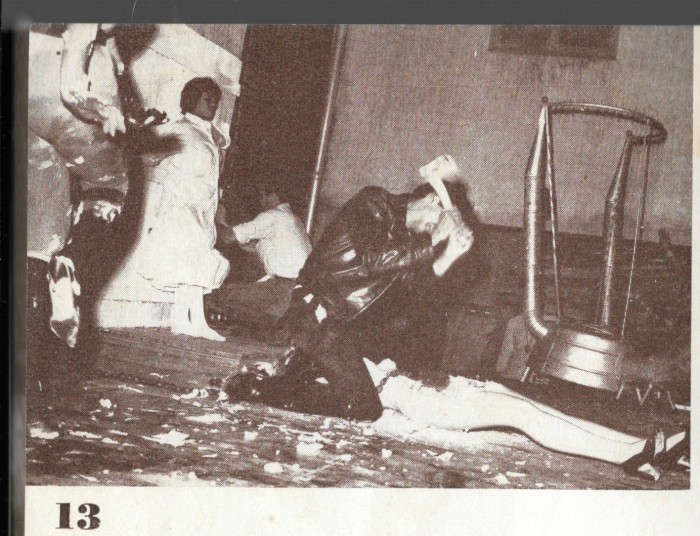

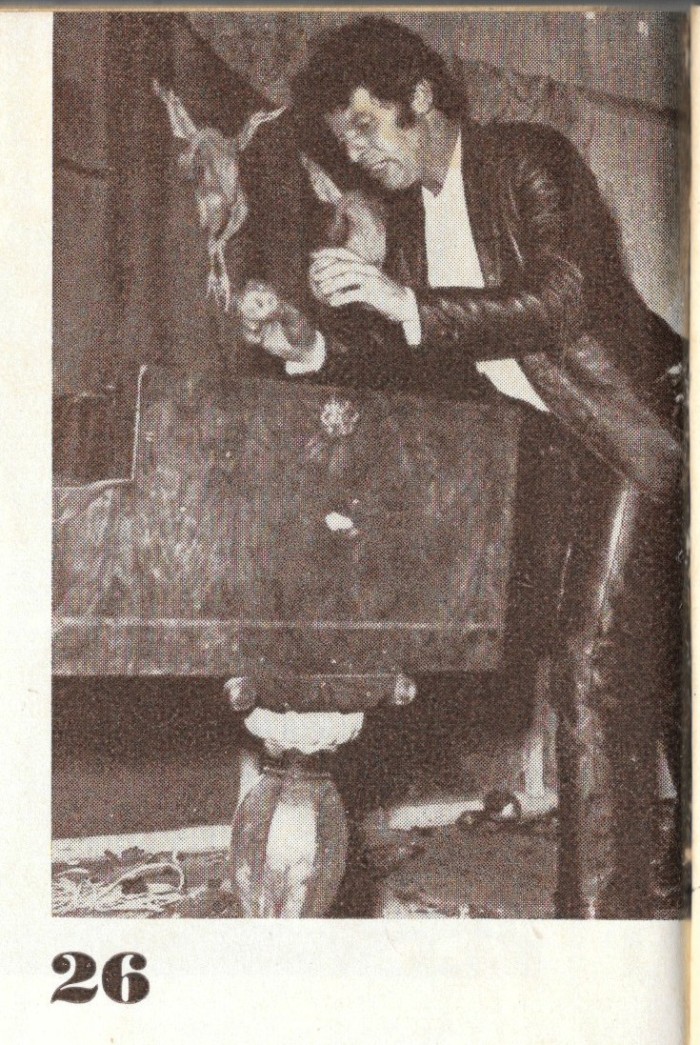

The first physical manifestations of what became “Panic theory” were largely improvised, one-time events and interventions called efímeros pánicos or Panic ephemerals. They involved the participation of all manner of artists, musicians, poets, actors, dancers, prostitutes and performers engaging in a chaotic and delirious production of simultaneously occurring collective and individual actions. Loose schematic scripts were developed by Jodorowsky or by the participants themselves encouraging a truly interdisciplinary model to art making.(5) They performed with numerous props and objects, some of them created for the event (such as musical instruments) and others that could be used for improvisation, including quotidian elements like eggs, shaving cream, milk, baby carriages, axes, and tortillas. Through the shock of the chance encounter with these spontaneous action, Jodorowsky hoped a type of therapy would be performed at the efímero. The interaction with objects and materials was meant to be a “real action” and not an act of representation.(6) Having been removed from the role of “spectator” and liberated from “individual thought”, promoting a form of cathartic release from the crisis of contemporary life.(7) By participating in the Panic party, the common man is transformed into a “Panic man” through a strategy that is akin to electroshock therapy.

According to his text in Teatro pánico (first published in 1965), the three ingredients of “panic” are: euphoria, humor, and terror.(8) If we turn to the little extent documentary evidence of the ephemerals, it is clear that these elements were consistently employed. In a 1963 ephemeral at the Academy of San Carlos (the only well documented early example), Mannequins were violated with axes, women were given haircuts, a piano was destroyed and set on fire and the flames then used to roast several chickens.(9)

The 1965 ephemeral in Paris (part of a panic spectacle organized with Arrabal and Topor), features such salacious activities as Jodorowksy himself,- initially dressed as Parisian police officer- sacrificing live chickens, their spilled blood then smeared on the naked and frantically gyrating bodies of female dancers. He even pummeled their bodies with the headless carcasses against a background of beat pounding drums. Towards the end of the disturbing scenario, a crazed Jodorowsky, was taken by a hooded figure resembling death. This figure began to smother him with an object resembling a large plastic vagina. Eventually he escaped, using an axe to hack his way through the vagina. After emerging on the other side, he was received and embraced by this figure of death, completing his transformation into the “panic man”.

An abandonment of social hierarchies was also a desire effect of panic, and the delirious combining of disparate elements and actions were meant to call the authority of these constructions into question. But as was insightfully suggested in a recent review of Jodorowsky’s retrospective in Bordeaux, there is a curious and shocking reliance on the violation of the female figure throughout the ephemerals.!10) While this might be reflective of the state of feminism in Mexico during the 1960s as well as a misogynistic stance on the part of the artist, the shocking treatment of women (and animals and, at times, the disenfranchised) in the ephemerals verges on the border of “shock for shock’s sake.”

This problematizes panic theory’s proposal to offer respite from societal ills when viewed from a 21st century perspective, yet the fact that the ephemerals continue to have a shocking effect raises further questions over the effectiveness of the panic ephemerals. Can and how might artists present opportunities for a collective healing in today’s world? How do we redefine an aesthetic of shock in a landscape inundated with repeating images of chaos and terror? That Jodorowksy’s evocation of panic during the 1960s and 70s continues to provoke both outrage and veneration in audiences, suggests that there might be potential for a collective shock therapy to generate new social and political models even today.

Notes:

(1) “eran hombres de corbata que hablaban de política y no de arte, eran burócratas…” Ignacio Maldonado Llobet and Lourdes Sánchez Puig, “La Osadía Jodorowsky, los primeros happenings latinoamericanos,” (masters thesis, Universidad Iberoamericana, 1994), p. 51.

(2) Cuauhtémoc Medina, “Recovering Panic,” in Olivier Debroise, ed., La era de la discrepancia: Arte y cultura visual en México / The Age of Discrepancies: Art and Visual Culture in Mexico; 1968–1997 (Mexico City: UNAM / Turner, 2006), 98.

(3) Alejandro Jodorowsky, “Hacía el ‘efimero’ pánico o ¡sacar el teatro del teatro!”, in Teatro pánico (México: Era, 1965), p. 12-13.

(4) Rita Eder, “Two Aspects of the Total Work of Art: Experimentation and Performativity,” in Desafío a la estabilidad: procesos artísticos 1952-1967. (Mexico City: MUAC/UNAM, 2014), p. 65-81.

(5) Jodorowsky, “Hacía el ‘efimero’ pánico o ¡sacar el teatro del teatro!”, p. 12. The recent exhibition, Desafío a la estabilidad: procesos artísticos 1952-1967 (MUAC, UNAM, 2014) firmly positioned Jodorowsky as a central figure in the development of non-traditional and interdisciplinary art practices and his relationship to the artists of the Ruptura generation in particular.

(6) Ibid., 15.

(7) Ibid., 13.

(8) Ibid., 12.

(9) “Documento pánico,” in Teatro pánico.

(10) Daniel Spicer, “Alejandro Jodorowsky: never belonging,” Wire (August 2015). Accessed 8/31/2015. http://www.thewire.co.uk/in-writing/columns/alejandro-jodorowsky-38280#.VeCQHbiOAqI.facebook.

Comments

There are no coments available.