17.08.2015

Bernardo José de Souza’s interest on how contemporary society relates to past, present and future times has led him to investigate science fiction as a powerful tool for artists and curators worldwide who challenge current political views.

Rio de Janeiro, some year in the future

A city partially underwater and devoid of human presence

Those who survived the great wave of the summer of 2074 could barely stand the torrid temperatures that struck down capybaras, monkeys, and humans with equal force the following year. Such a terrible, far-reaching public calamity was unheard of in these parts: a devastating urban exodus never before seen; not even Graciliano Ramos would have ventured to conceive of such a thing.

They headed southwards, those wretched souls, in search of fresh water, a friendly shoulder, milder temperatures, any sign of hope. But God only knows what they came across in that frantic southern flight, fated to fail like all human undertakings since time immemorial.

Out of sheer stoicism, I decided I would not budge. I would stay behind on my own, take refuge in this decadent tropical mansion in the middle of the Atlantic forest – sparser with each day that passed – surrounded by the memories that had filled the hard years I had devoted to myself and the few that came here in search of a secret embedded in the grotto, the tower, the aquarium, the oca, or even in Corcovado (that mountain that can be seen from here and reached by anyone willing to climb that treacherous hill, go straight on, and come face-to-face with He who has always so carefully kept his back turned to me, this poor creature, and my property).

At first, I counted the days like Penelope, weaving the web of my own memory and embellishing it here or there with a smattering of fiction. But I ended up losing count of the centuries that dragged by, and so I surrendered to the pleasure of observing the sneaking changes to the wildlife, my semblance, and the areas surrounding this mansion.

Things and creatures started to appear, sprouting out of nowhere, creeping out of the shadows, taking over my gardens and rooms as if they were theirs. And it was always at night – or rather, at the hour of the wolf – that this magic took place, leaving me ever more intrigued. Species never before seen, frightful beings, unintelligible voices haunted me without rest or respite.

I never tried to talk to them or even to smile, afraid I would look foolish, tongue-tied, like some tourist in a strange land.

But I was relieved to see that they were content just to snoop around my collection. Sometimes they would rearrange works, objects, belongings, and knick-knacks with silly things of their own, because they also produced oddities, which, I should add, meant nothing to me. One way or another, this land was being explored again. What curiosity would guide the fate of these folks?

The Negative Hand (1)

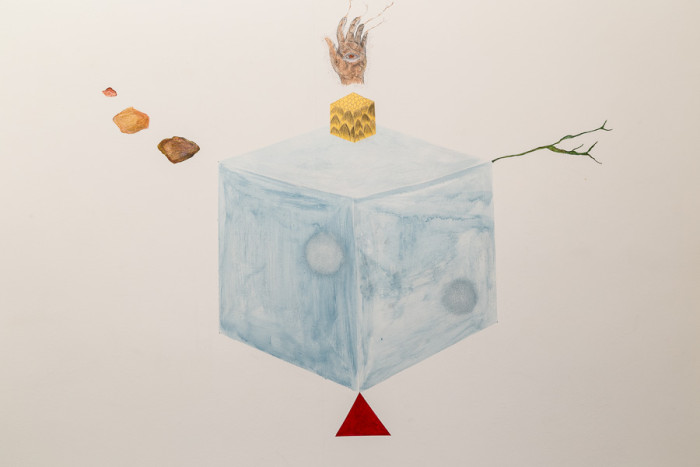

Les Mains Négatives, a film by Marguerite Duras inspired by the mythical paintings from the Upper Paleolithic discovered in the caves of Gargas, France, served as the starting point for the construction of this exhibition. Broadly inspired by science fiction, this project addressed the Parque Lage (2) space as a kind of archaeological site explored by different civilizations in the distant future, after the people of Rio de Janeiro fled the unbearable temperatures and a great tidal wave left the city partially underwater in 2074.

The visitors to Parque Lage – assuming the role of explorers of the future – came across the remains of past civilizations: sculptures, images, architecture, and ruins of great iconic value, imbued with symbolism. Largely devoid of verbal or written language, this exhibition was designed to allow the visitors to relate in a more phenomenological manner to the artworks scattered around, not just in the rooms normally devoted to art – the entrance hall and Cavalariças galleries – but also in the constructions around the mansion: the grotto, oca, tower, aquarium, and the former slaves’ laundry, as well as the forest itself.

Based on the perception of space as the expression of the “unequal accumulation of time,” as postulated by geographer Milton Santos, The Negative Hand took Parque Lage as a geographical space where different times coexist as juxtaposed layers that constitute an atemporal dimension permeated by fiction, thus engendering a heterotopian zone that obeys its own isolated, internal logic and is therefore cut off from the reality of the outside world.

Although the works selected for this project do not deal objectively with science fiction, they do indicate a world in transformation, where the body and recognizable forms, whether from nature or the world of material culture, are subject to impacts or mutations in their organism, structure or architecture.

A range of artists, from different generations and nationalities contributed to the conception of a universe of post-apocalyptic overtones, whose aesthetic and political tendencies indicate the philosophical and cultural landscape of today, constituted in a zone of contrasts and discrepancies that constantly forces us to look at the past through the lens of history and predict the future based on foundations that are just as precarious and provisional as our capacity to conceptually articulate the period in which we live.

Afterthoughts

The conception process of any art exhibition demands from its curator to establish simultaneous relations to past, present, and future times. We start from previously accumulated knowledge – be it on an individual or collective plane – to shape the body and soul of an exhibition but furthermost we must be able to embrace the immediate reality, in all its potency and incoherence, in order to grow organic and fruitful relations with contemporary thought. On the other hand, we are tempted from degree zero of the project, to incur in futurological exercises, avid as we are to envision a wide range of critical relations vis-à-vis its final result, thus anticipating the role of the critic and even of the art historian. This is an exercise that is capable of revealing latent aspects in our thinking, thus offering an external perspective whose dialectic nature is different from ours. As such, we are in permanent relation with diverse temporalities, although responding to questions whose origin lies in the present, framed by particular preoccupations that could only emerge from a given moment in time.

My experience in the development of The Negative Hand could not have been different, and the preceding texts seem to me quite revealing of that process as a whole. The first one is a absolute literary reverie that came to me unannounced and was written in one single breath, an intuitive response to a curatorial project that had been taking shape in my mind already for a few months, maybe even a year. Above all, it responds to the desire to articulate ideas stemming precisely from the primary source of my inspiration, namely science fiction literature. That is how the sci-fi short story emerged, without the usual sieve and ties usually imposed by academic thinking.

This interest in science fiction dates back to my childhood. But it was only when curator Sofia Hernandez Chong Cuy sent me a review in The New Yorker about Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy (3) – which raises a number of political issues as it builds a future scenario for humanity – that I fully understood that science fiction in literature (and more recently in the visual arts, though less in Hollywood movies, given the ingredients of American political and cultural hegemony implicit to the genre) has been operating as one of the most powerful platforms to discuss contemporary politics.

In 2014 I planned an exhibition for Largo das Artes (Rio de Janeiro) that was based on a workshop on curatorship. At the time, I was interested in the notion of “second nature,” taking different perspectives according to the author, from Marx, Freud, and Hegel to Sam McAuliffe. The discussion of habits, cultural norms and conventions, the superstructure, and the whole naturalization of behaviors and procedures that are anything but natural to man led me to study post- or trans- humanist theories, which in turn directed me to Catherine Malabou and her compelling essay on destructive plasticity, entitled Ontology of the Accident.

In this work, she takes a step beyond the normal conception of plasticity as a phenomenon that covers just the giving or gaining of shape through gradual and flexible transformation, without any cuts or radicality. Rather, what the author proposes is an investigation into the annihilation of a being’s form and essence when they survive an accident. Her classic examples, which are unique to this day, are people with progressive degenerative neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s and war trauma victims. Her initial reference is Franz Kafka, who investigates a transformational process that is restricted to an external aspect, as is the case of Gregor Samsa when he wakes up as a bug in The Metamorphosis.

Although the idea of destructive plasticity is conceived as an incipient form by Malabou, it can be transposed into the current debate about the end of time, the apocalypse, the extinction of the human species, and the place of nature, which will eventually sweep man off the face of the earth. Everything may change but nature will remain, even if transformed.

From there to science fiction it was a natural progression. In that first 2014 exhibition at Largo das Artes, called To See What Is Coming, the future emerged from the works of Neil Beloufa (Kempinski), David Cronenberg (Crash), and Gisela Motta and Leandro Lima (looking into the exchange between Hal’s artificial intelligence and the human crew in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey).

In this new exhibition, the curatorial strategy is shaped by other tendencies. Above all, the chance to conceive a project especially for Parque Lage and not for a museum or gallery with white walls in the middle of some cosmopolitan city somewhere in the world. So Parque Lage’s geography and architecture were clearly important from the outset for the curatorial approach, as this is a space where the natural world and human constructions coexist in apparent harmony. They are overlapping planes that form a single landscape that I’d call decadent. In this setting, the artworks are on equal footing with the mansion and its eclectic architecture (and tropical contours); with the grotto and aquarium in their forms that simulate nature; with the vernacular structure of the kupixawa (a primitive indigenous architecture/technology) erected just a year ago; with the forest and the French gardens behind the park; and finally, with Christ the Redeemer itself, overlooking everything and everyone. This project could never be taken somewhere else; it was born in the bosom of the forest and the architecture of Parque Lage, and by extension in the city of Rio de Janeiro – a prime example of symbiosis between natural and urban environment unmatched anywhere else in the world.

Besides geographer Milton Santos’s aforementioned thesis about space being the result of the unequal accumulation of time, my research was guided by Michel Foucault’s formulations about heterotopias and Fredric Jameson’s exhaustive book on “archaeologies of the future,” where he establishes the genesis of utopia and science fiction with one as a variant of the other.

Also, the possibility of making contact with a different kind of public than the people who usually attend art institutions was essential, since Parque Lage is also visited by tourists who are attracted to the eccentricity of its architecture and the stunning beauty of the surrounding landscape. I hope that when they come across the works scattered around the grounds they will relate to them in a rather intuitive way – guided less by museological codes and more by the spontaneity of the encounter with works that sprout out of the ground and walls almost like anomalies of nature, or as if they were real or fictive remnants of times past. The grotto, the tower, and the aquarium are all man-made ruins, and therefore fictional in the term’s broadest sense, like the history of Parque Lage, marked by fictional films (Glauber Rocha’s Terra em Transe and João Pedro de Andrade’s Macunaíma were shot there), and projects that were never carried through (like Lina Bo Bardi’s project for the school in 1965 and Sérgio Bernardes’s plans for a Museum of the Indian in 1968). Reality and fiction are paired up in this exhibition, just as historical narrative is understood as one great work of invention.

In today’s world, we are always being urged to look to the past and into a precarious, provisional future of apocalyptical overtones, the only possible scenario in today’s philosophical and political context in view of the absence of projects to sustain and qualify the experience of the present time.

Lastly, one question has been haunting me ever since I wrote that science fiction introduction: who could be this narrator speaking to us from the future? What kind of discourse does he articulate? What is the purpose of this literary introduction?

This narrator (the diary entry is signed by my namesake: Bernardo José de Souza), although speaking from the future, does not exactly constitute a subject of modernity, given his predilection for a Portuguese that is, if not archaic, at least outdated as well as his references to icons of classic literature or early twentieth century (the mythical Penelope and the great Brazilian realism writer, Graciliano Ramos). In a first examination of this character, there is no trait that fully represents modern thought, as no loathing against heritage and tradition can be remarked in his character; he preserves such a strong relationship with the past that he decides to remain in Rio de Janeiro despite the tsunami and the scorching heat of that annus horribilis of 2074 – a hundred years after my birth.

Who would then be this creature? A bourgeois conservative, refusing to abandon his property, his belongings, his life, in short, his past? Or was he a romantic, driven by a relentless curiosity, challenging even God, the creator? Bernardo, by stoically deciding to stay in Rio’s soil, ends up being visited by intriguing and unknown beings, future civilizations that will provide absolute awe and delight to him. He traverses time, survives for weeks, months, years, and centuries on end, in spite of the imminent apocalypse around him.

And while gaining unprecedented longevity for a human, the narrator amounts to an almost divine status, allowing him to monitor everything and everyone from this elevated perspective. An exoperspective – this characteristic point of view in science fiction that lets us see our world from outside – is precisely the ingredient that propels us to overcome the subordinate and selfish condition that drives us to ignore otherness, and even to recognize life and universal time as something of much higher scale and importance than our mundane anxieties.

Bernardo José de Souza

All pictures ©Pedro Agilson

Notes:

(1) The Negative Hand, with Antoine Guerreiro do Divino Amor, Avalanche, Barrão, Cinthia Marcelle, Cyprien Gaillard, Cristiano Lenhardt, Daniel Steegmann Mangrané, Dominique Gozález-Foerster, Elena Narbutaite, Erika Verzutti, Felipe Braga. Gintaras Didziapetris, Gustavo Torres, Igor Vidal, Igor Gaviole, Leo Felipe, Leticia Ramos, Luciana Brites, Luiz Roque, Manoela Medeiros, Mariana Kaufman, Marguerite Duras, Mauricio Ianês, Michel Zózimo, Pablo Pijnappel, Rafael RG, Ricardo Castro, Rodrigo Braga, Rodolfo Parigi, Stefan Panhans, Tiago Rivaldo, Tomaso de Luca, and Vera Chaves Barcellos.

The exhibition took place at Parque Lage, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, between the 19th of June and the 6th of August 2015, under the invitation of Lisette Lagnado, the Director of the School of Visual Arts of Parque Lage, as part of her Guest Curator Programme.

(2) Originally a sugar refinery building, the palace was refurbished in the 1920s and until today holds the same architectural eclectic style that was conceived by Italian architect Mario Vodret, by request of Henrique Lage and his wife, Italian opera singer Gabriella Bezansoni. In the 19th century, landscape painter John Tyndale was called to design the park so that it would echo English romanticism and his fascination for nature. Between the 1920s and 1940s, Parque Lage was the scene of diverse night gatherings of the artistic and bohemian circle of Rio de Janeiro around the opera diva.

(3) http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/our-greatest-political-novelist?mobify=0

Comments

There are no coments available.