11.06.2020

Reaffirming the relevancy of Afrofuturism’s legacy and vision in the present, Reynaldo Anderson and Tiffany E. Barber suggest technology as a tool, albeit born of White Supremacy, to be “hacked” by global anti-racist movements in order to fight the agonizing hydra of Necrocapitalism.

The Black Angel of History has been speaking to the souls of Black Folk since the beginning of time. The Angel has known rivers. The Angel was with us at the battle of Tondibi, Cape Coast castle, Jamestown, and Adwa. The Angel whispered to Denmark Vesey, [1] Nat Turner,[2] and Nanny,[3] and carried them to heaven. The Black Angel has a message for us now. The Black Angel of History is the messenger of an African worldview in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and mass death within a post-U.S. world order, marked by twenty-first century Necrocapitalism.[4]

Necrocapitalism is a reflection of the historic formation of racialized capital in relation to settler-states, imperialism, colonialism, and post-colonialism. Extending the work of Achille Mbembé (2003), Necrocapitalism and its forerunner Necroeconomics animate what Marx (1990) refers to as the originary accumulation of enslaved Africans as a foundational feature of capitalism.[5] The Angel too, heard, and bore witness to the cries of the people as they were carried across the ocean and deserts like Black gold to sing their songs of sorrow as strangers in strange lands. The accumulation of their Black DNA has contributed to the racialized distribution of twenty-first-century life, death, dispossession, and subjugation.[6] In our current moment, within the context of the global COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent economic collapse, information capitalism and its accumulation now function as an openly Necrocapitalist system. Under and against the racialized hierarchies of the Western economy, the Black Angel of History tells us peoples of African and indigenous descent are faced with health disparities and unsafe labor conditions within our current Necrocapitalist system, an extension of slavery. These workers’ former white masters and conqueror-settlers require them to labor in plants, participate in the food industry with little to no benefit, and toil in the Prison-Industrial complex until death, like their ancestors.

The Angel has traveled across beyond time and space to prepare us for a future African Zion beyond this place of wrath and tears. The Angel whispered and sowed secret Afrofuturist visions of Saturn in Sun Ra’s ear to accelerate to the stars beyond the gravity of White supremacy.

The Black Angel of History reminds God’s sable children of the legacy of medical apartheid and enslaved African women screaming under the scalpel of western science. COVID-19 has exposed the incompetence of Donald Tr*mp, B*ris Johns*n, Jair Bols*naro, and other elected officials. It has also revealed the limits of Neoliberalism as an oppositional force to global fascism and white supremacy, as well as the failure of populism as a governing philosophy. These interlocking phenomena are the background for the ideas explored in this essay, which began as a series of conferences and salons organized around the topic of Afrofuturism’s second wave in academic spaces like UNESCO Paris (France), Loyola Marymount University, Emory University, Duke University, Jackson State University (United States), and others over the last several years. The Black Angel of History has seen African-descended peoples of the continent and the diaspora through the rise and fall of kingdoms, the East and West African slave trades, and other formative struggles. In the early twenty-first century, it manifests as an Afrofuturist harbinger of things to come. The Black Angel of History now resurfaces to instruct its people to go back and fetch tools they have forgotten and use these tools to weather the struggles to come.

Drawing together second-wave Afrofuturism and its Black Speculative Arts Movement progeny, this essay centers the Black Angel of History as a response to what Sunny Singh and Subhabrata Bobby Banerjee call Necrocapitalism. The term Afrofuturism emerged as an explanatory concept for the African American imagination’s engagement with science fiction, music, art, and technology following the end of the Cold War and the emergence of the World Wide Web. Since this time, a new wave of Black speculative art and design aimed at re-imagining both the past and the hotly contested present in order to catalyze the future has come to the fore, a movement unto itself. Afrofuturism 2.0, the Black Speculative Arts Movement (BSAM), and Necrocapitalism all concern the ways in which structures of containment circumscribe everyday Black life. These shared concerns produce tension, calling forth the Black Angel of History that arises at the intersection of forward-thinking, extreme economic and environmental collapse, mass death, and destruction.

The Angel has traveled across beyond time and space to prepare us for a future African Zion beyond this place of wrath and tears. The Angel whispered and sowed secret Afrofuturist visions of Saturn in Sun Ra’s ear to accelerate to the stars beyond the gravity of White supremacy. Afrofuturism 2.0 is a transnational, trans-contextual, diasporic, and cultural worldview that interrogates linear constructions of the past, present, and future in the humanities and sciences in order to overturn Eurocentric motifs of identity, technology, time, space, and religion. It expands early Afrofuturist ideas into the areas of theoretical and applied science, metaphysics, social sciences, aesthetics, and programmatic spaces. It acknowledges the increasing necessity to challenge a trenchant and growing wave of fascism and anti-Black sentiment. These shifts have all contributed to establishing Afrofuturism 2.0’s transdisciplinary, Pan-African reach. Although Afrofuturism conceptually originated in the North American African diaspora, practitioners in Africa and its larger diaspora, as well as non-African adherents, have embraced and begun revising it in relation to their own geopolitical contexts and conditions. Furthermore, contemporary Afrofuturism is maturing in metaphysical areas such as cosmogony (origin of the universe), cosmology (structure of the universe), speculative philosophy (underlying pattern of history) and philosophy of science (the impact of theoretical and applied science on society, culture, and individuals).[7] This 2.0 version extends the reach of radical Black visual art, literature, theater, social and applied sciences, and critical theory of the long twentieth century in the U.S., and is currently experiencing a generative and historic moment in the era of Necrocapitalism.

In the face of international fascism, the mass death stemming from Necrocapitalism, climate change, and other crises to come, the Black Angel of History reorients and reconceives praxis for Pan-African liberation and survival.

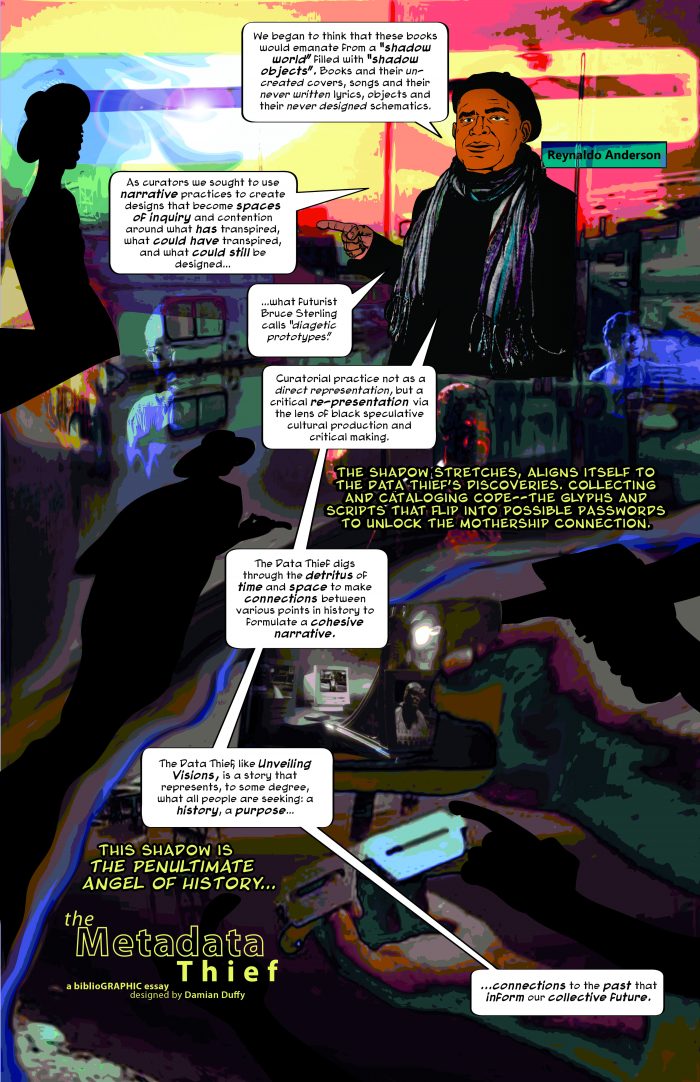

The Black Speculative Arts Movement (BSAM) is situated here. As an act of resistance to racialized capitalism, the Black Speculative Arts Movement institutes new foundations for global liberatory systems. BSAM is an international network of creatives, intellectuals, and artists representing different positions and bases of inquiry that include: Afrofuturism, Astro Blackness, Afro-Surrealism, Ethno Gothic, Black Digital Humanities, Afro-future female or African-centered Science Fiction, The Black Fantastic, Magical Realism, and The Esoteric. Frequently these positions may overlap around the terms speculative and design, and even appear to be incompatible, yet they often interact at the nexus of technology and ethics.[8] The movement emerged following the opening of the Unveiling Visions: Alchemy of The Black Imagination exhibition curated by John Jennings and Reynaldo Anderson and held at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City in 2015. There in New York City, the Metadata Thief awakened to the call of the Black Speculative Arts Movement. BSAM has since become a global entity with semi-annual events regularly taking place on three different continents.

The summer 2020 virtual exhibition Curating the End of the World, the latest large-scale BSAM event, reconfigures how we perceive historical process through speculative design and data mining, concepts first introduced in the didactic materials for Unveiling Visions. The two-part, online exhibit locates the Black Angel of History and Afrofuturism 2.0 within the unique sociopolitical and geographic contexts that comprise the Pan-African sphere to critique Necrocapitalism and the acceleration of social life for Black and African people.[9] Aesthetically, this conceptual move bridges Frankfurt School theorist Walter Benjamin’s angel of history with the data thief to form the Metadata Thief, or the Black Angel of History—a figure whose roots originated in the experimental documentary, The Last Angel of History (1996). Directed by John Akomfrah and written and researched by Edward George of the UK-based Black Audio Film Collective, the film outlines the origins and significance of Afrofuturism vis-à-vis the journey of a time-traveling data thief. The Data Thief explores Black music, speculative thought, technology, Black transatlantic culture, and neoliberalism across time and space. This figurative creation echoes Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History and its relation to Angelus Novus (New Angel), Paul Klee’s monoprint of 1920. The abstract print shows a bird-like stick figure staring at something out of frame. With mouth open and wings spread, the figure appears to be frozen at the moment, contemplative, yet perched to move. This look is how Benjamin pictures the angel of history: a view of the historical process as an unceasing cycle of suspension and melancholia wherein the figure faces the past with its back to the future. Benjamin’s important work, influenced by Jewish metaphysics within the kabbalah tradition and was written during the era of monopoly capitalism. Although Benjamin misses the opportunity to address Rassenhygiene (race purity) and the plight of the Afro-German population, his essay provocatively critiques historical materialism and vulgar Marxism in the wake of the failure of the 1919 German Revolution and the betrayal of Stalinism. The Black Angel of History goes beyond the work of Benjamin and the Black Audio Film Collective, parsing the available metadata of global oppression and injustice. In the face of international fascism, the mass death stemming from Necrocapitalism, climate change, and other crises to come, the Black Angel of History reorients and reconceives praxis for Pan-African liberation and survival.

Pan-Africanism has been primarily defined as a cultural and political construct that over-relied on colonial records for data.[10] The Black Angel of History amends this outmoded framework. The Black Angel of History travels and navigates via Black Software, a coded technocultural neural network of algorithms and database aggregations—archival and real-time—held together by the compression of time and space, that has resulted from information capitalism and its attendant technological structures, such as the hardware of cables that re-draw the colonial sea routes.[11] Because of the different geographic locales, sometimes modulated by varying APIs (application program interfaces) throughout the African continent and the Pan-African diaspora, thinking and doing Afrofuturism in this way could potentially impact education, crisis, and risk assessment, economic development, public policy, and the political economy of the Black technosphere.[12] Significantly, the Black Angel of History redresses previous assertions concerning Afrofuturism and its underdevelopment in relation to accelerated global flows, contemporary and future forces of production, and social reality.[13]

For example, the theory of Accelerationism holds the idea that capitalism should be accelerated in order to generate radical social change. Accelerationism is a reflection of the desire of Silicon Valley Capitalists to create and control vectors of life and return to a Eurocentric, Eden-like vision of society with its ability to consume and rule, undisturbed by the presence of Black and Brown bodies. Contemporary theories of Acceleration fall within two distinct camps. On the right is an anti-humanist (crypto-fascist) impulse, usually associated with British philosopher and short-story writer Nick Land. Amid the current global revolt, police and state actors as well as white nationalist organizations have appropriated the anti-humanist impulse in right-wing accelerationism to provoke a race war. On the left is a post-Marxist perspective and aesthetic tendency that moves back and forth between poles of capitalist alienation spurred by technology and hyper-commodified art objects that drive their own markets within the logic and desire of late capitalism.[14] Correspondingly, its adherents believe this will hasten its self-destructive tendencies and lead to its collapse.[15] The global economic collapse of 2008 ignited contemporary articulations of Acceleration as a technological-social direction toward a post-capitalist order.

However, recent scholarship asserts, like a portmanteau, that Acceleration already existed in formulations of Blackness and Afrofuturism recoded as Blacceleration. Significantly, the current left versus right conflict in Accelerationism ignores the role slavery played in capitalist accumulation and the role of agency put forth by Black Radical Tradition scholars like Cedric Robinson, C.L.R. James, Claudia Jones, and others.[16] The Black Angel of History has come forth sounding the call to African people to resist the postmodern Babylonian Empire and its right-wing settler utopianism of Make America Great Again as well as giving the warning to be aware of Asian Tigers from the East while reminding them of other suns. Thus, in the context of racialized capitalism and the corresponding destruction of Black life, the Black Angel of History seeks to break apart the human-capital binary that Accelerationism advances and reposition itself as a beacon of radical change.

The authors thank Natasha A. Kelly and Andrew Rollins for their editorial comments.

“Denmark Vesey (also Telemaque) (c.1767 — July 2, 1822) was a literate, skilled carpenter and leader of African Americans in Charleston, South Carolina. In June 1822 he was accused and convicted of being the leader of “the rising,” a potentially major slave revolt which was scheduled to take place in the city on July 14. He was executed on July 2.” More information

“Nat Turner’s rebellion was one of the largest slave rebellions ever to take place in the United States, and it played an important role in the development of antebellum slave society. The images from Nat Turner’s Rebellion — of armed black men roaming the country side slaying white men, women, and children — haunted white southerners and showed slave owners how vulnerable they were.” More information

“Nanny, known as Granny Nanny, Grandy Nanny, and Queen Nanny was a Maroon leader and Obeah woman in Jamaica during the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Maroons were slaves in the Americas who escaped and formed independent settlements. Nanny herself was an escaped slave who had been shipped from Western Africa. It has been widely accepted that she came from the Ashanti tribe of present-day Ghana.” More information

Generally, Necrocapitalism names a form of capitalism where a country’s trade and industry are founded on, linked to, and dependent on death and the profits accruing from it. It provides a framework for understanding how different forms of institutional, material, and discursive power operate in the global political economy and the violence and dispossession that result from this paradigmatic shift.

See Achille Mbembé and Libby Meintjes. “Necropolitics,” Public Culture 15, 1 (2003), 11-40. See also Karl Marx, Trans. Ben Fowkes and David Fernbach, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1 (New York: Penguin Books Limited, 1990).

See Subhabrata Bobby Banerjee’s “Necrocapitalism,” Organization Studies 29, 12 (2008), 1541-1563. See also Sunny Singh’s “The end of necro-capitalism (but not necessarily capitalism),” Media Diversified (2017),

See Reynaldo Anderson and Charles E. Jones, eds. Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro-Blackness (Latham, MD: Lexington Books, 2015).

See Reynaldo Anderson, “Afrofuturism 2.0 & the Black Speculative Arts Movement: Notes on a Manifesto,” Obsidian: Literature & Arts in the African Diaspora 42, 1-2 (2016), 230-238.

For the exhibition, Curating the End of the World, see

See P. Olisanwuche Esedebe’s Pan-Africanism: The Idea and Movement, 1776-1991 (Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1994).

Editor’s note: From our archives, we recommend reading: Cláudio Bueno, “Amerelo-Ouro” en Vibrán imágenes en la oscuridad, Terremoto #16 (Fall 2019), available in

See Charlton D. McIlwain, Black Software: The Internet & Racial Justice, from the AfroNet to Black Lives Matter (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019); Nick Srnicek, Platform Capitalism (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2017); and Cécile Wendling, Jack Radisch, and Stephane Jacobzone, “The Use of Social Media in Risk and Crisis Communication,” OECD Working Papers on Public Governance 24 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2013),

See Mark Bould’s “The Ships Landed Long Ago: Afrofuturism and Black SF,” Science Fiction Studies 34, 2, Special Issue Afrofuturism (July 2007), 177-186.

See Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams’ Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work (London/New York: Verso Books, 2015/2016).

See Jason M. Adams’ Occupy Time: Technoculture, Immediacy, and Resistance after Occupy Wall Street (New York: Palgrave, 2013).

See Aria Dean’s “Notes on Blacceleration,” e-flux journal 87 (December 2017), < https://www.e-flux.com/journal/87/169402/notes-on-blacceleration/>

Comments

There are no coments available.