21.03.2016

Natalia Valencia and Terence Gower discuss abstraction, the mental thresholds of modernism and the architectural hangover.

Natalia Valencia: So let’s start at the beginning, or at the morning after…

Terence Gower: When you suggested “hangover” as a theme for our conversation it made me think of what I always refer to as the “New Deal hangover,” a term I use for the years immediately following the second world war in the US—a period I’ve been studying for many years—when Roosevelt’s great pre-war public projects continued to function pretty much as before (compare to the current state of public education and healthcare in the US).

I think we can all agree that a massive political shift took place in the US in the early 1930s: a democratic government was elected with a new emphasis on public infrastructure projects, in contrast to the every-man-for-himself spirit of the 1920s. In my research I found that the general spirit of public investment remained intact even through the madness of McCarthysim. That door was closed by Reaganomics in 1980. You can almost say that 1930 to 1980 was a strange 50 year hiatus within a long sort of Darwinian modus operandi—survival of the fittest—, which I consider a founding American ideology. That means the period we’re talking about, including my “New Deal hangover” was part of a peculiar leftward shift in the country’s history.

I love your idea of the “day after the party” because when viewed from the right end of the political spectrum, the public-mindedness I just mentioned was a big party paid for with public funds: “We’ve got to pull the plug on the sound system, stop throwing money around, and get serious (about personal gain)”. And vice-versa, the New Deal was about putting an end to the capitalist free-for-all of the roaring 20s.

This viewpoint underlies my research on post-war US public architecture, including foreign buildings like embassies. A couple of years ago I was reading an article about the new US Embassy in Baghdad, built in 2007, after the invasion. The building was portrayed as a total scandal: it was the most expensive and largest embassy built by any country anywhere in the world, but remained only partially occupied. In the project that resulted from this embassy research (Baghdad Study Case, 2012-2014) I avoided the term “Iraq war” as I have always considered what transpired between these two countries an illegal attack, invasion and occupation.

I found some mention of an earlier embassy in Baghdad and that gave me insight into a post-war embassy-building program that started in the late 1940s, (also part of the New Deal hangover.) We’re talking about a relatively enlightened and progressive period in the US, where creative thinkers in the State Department started to feel like the architectural projects abroad could be used as public relations tools for the government. Again, consider this in contrast to the new super-fortified embassy buildings, sometimes referred to as “super-bunkers”. Up until then, embassies looked like miniature White Houses—plantation style—with columns out front that could be read as a reference to slavery and other negative things from American history. The State Department formed a board of very forward-thinking architects, including people like Pietro Belluschi from Oregon, Ralph Walker from New York, and other leading modern architects from the period, with a very clear directive of projecting the idea of the US as a progressive country. They wanted to use materials like glass to represent transparency, to have cultural facilities like libraries and auditoriums right up front in order to give off a strong sense of public access and open doors. The idea was to both demonstrate and represent open access to information, in contrast to what they thought was happening in the Soviet republics, as this was the beginning of the cold war. When I first presented Baghdad Case Study at Haus of Kulturen der Welt in Berlin (2012), I used the city as an example of that American public relations program.

NV: Haus of Kulturen der Welt was a gift by the Americans to Berlin…

TG: Exactly, originally built as the Kongresshalle, the HKW building was a great work of US propaganda.

The US embassy in Havana was the second commission of this progressive US embassy project, after the Brazil embassy. They were both granted to the same architectural firm, Harrison & Abramovitz, who were also the master planners for the UN in New York. Harrison also did Rockefeller Center and right after the UN and the embassies, Abramovitz did the CIA headquarters in Washington! He was receiving all of these contracts for strong ideologically loaded buildings for the US government.

I’m a utopianist, so I was interested in how fucked up the US has always been yet with these moments of enlightenment and progress, which interestingly came out of places like the State Department. The design directive for the post-war embassy program is a great example of its progressive vision.

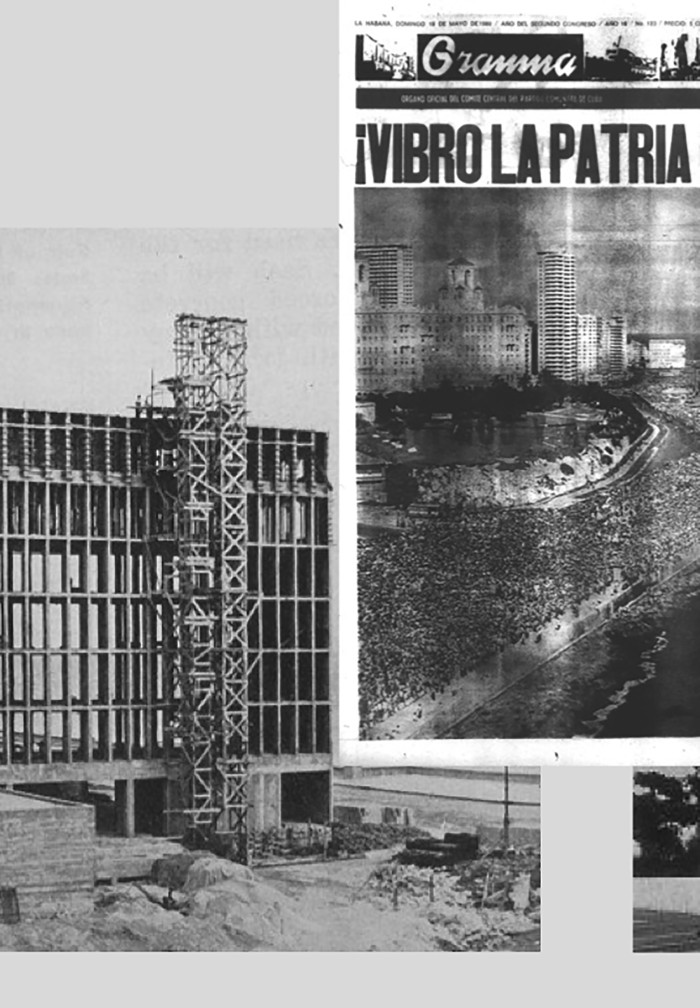

The US embassy in Havana was commissioned in 1949 and finished in 52′. It was occupied by the US government in 1953, but then of course in 1959 the Cuban revolution took place. It was not an overtly communist revolution at the beginning, so the US believed they could maintain their interests in Cuba. But soon rumors started about the nationalization of US companies. Castro went to the US a few months after the revolution, did a lecture in Princeton and other universities, asked for a meeting with the president… but Eisenhower went golfing instead. It was a slap in the face: Eisenhower thought Castro was a kid who was going to be deposed in a couple of months. Had he took that meeting, history could have been completely different. Instead, Richard Nixon, the vice-president, took the meeting and berated Castro for two hours.

The embassy continued to operate until 1961, when the US decided to break diplomatic relations because Cuba had started to requisition American property. The US is now seeking compensation for those requisitions, which is an interesting debate considering the billions of dollars of losses the embargo has cost Cuba, which is also seeking compensation. The embassy was basically shuttered in 1961, but the US still officially owned the building and kept maintenance staff there. Under Carter in 1977 they re-opened the building as a sort of pseudo-embassy called the US Special Interests Section until last spring when the embassy was re-opened. So this same building has lived different lives and acquired different meanings. What is fascinating to me is how the architectural form signified to each opposing side and how it was used differently for propaganda purposes.

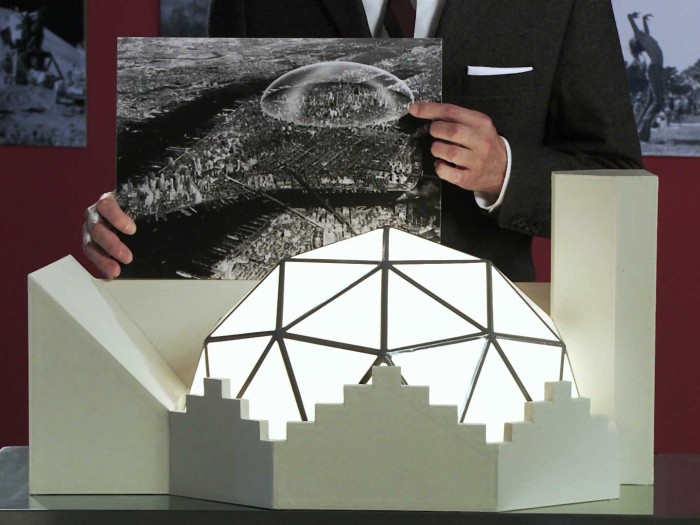

NV: For this Havana project, are you planning to produce something similar to Baghdad Study Case, were you take the abstract form of the building and de-contextualize it?

TG: Yes, exactly. With the Baghdad project I concentrated on the roof form of the residence of the US ambassador. I try to identify a form that somehow operates as a fulcrum in the research and argument—in that sense I work a little bit like a writer. In the Havana project I’m taking the ambassador’s balcony as the form to be worked on sculpturally all through the project.

The building was innovative structurally yet it never functioned well climate-wise. It was a perfect example of a universalist modern architectural solution that just didn’t function well. So in the 1990s they renovated the building and added a huge air conditioning plant on the roof, but they kept the balcony. When the building was completed, the State department criticized the balcony as a security risk as it shows where the ambassador is located. But the balcony stayed, becoming a symbol to me of the cultural/architectural limbo of Havana, where all construction stopped as resources dried up due to the embargo. It is hilarious to me as well because, what the hell were the architects thinking? It looks like a tribune, like something Mussolini would come out on to address the throngs. Soon after the revolution, but especially in the 80s around Mariel, the building became the focal point of massive protests organized by the Cuban government. The building became a convenient target for Cuban anger –beautifully orchestrated by the government. Architecture as the perfect ideological marker.

NV: At HKW in Berlin your installation of Baghdad Case Study could be read as an architectural element made to look like it was from the period of the HKW’s foundation.

TG: Yes, that one and the pieces that are coming out of the Cuba research share that trait of being in between function and non-function; they are in themselves an interrogation of the function of the artwork. Are they artworks, are they sculptures, pieces of furniture? The actual function is meant to be ambiguous. The HKW installation was about diplomatic dialogue vs. a breakdown of communication, and both the HKW building and the 1960 Baghdad embassy serve as clear examples. The HKW was built—as a congress hall—as a gift from the American people to the people of Berlin in 1957. I consider it an ideological Trojan horse, wheeled right up to the frontier between East and West before the wall was built. The architect called it “a shining beacon of freedom directed towards the East”. But the progressive mayor of Berlin, who had obviously had enough of conflict, thanked the Americans for the gift and put the building to use as a place for dialogue with the East. In 1989 when the wall came down it was turned unto the House of World Cultures, which seems both colonial and utopian.

NV: Going to another subject of interest in your work, I was wondering how you approach the relevance of sculpture nowadays?

TG: I think it’s more relevant than ever. I’m working on a public commission project now, just outside Geneva. In my proposal I specifically stated that I wanted to make a work that would relate directly to the body of the viewer, as this is what sculpture should do. It’s like architecture in that it speaks directly to the intelligence of the body. We are mostly tied to retinal experience, so sculpture has an important role in completing the sensory experience by giving the body its own encounter with the object. In much of my post-war sculpture series, which includes the Geneva commission, I’m analyzing the work of Barbara Hepworth. In one project, I rebuild a sculpture she designed for the court of the United Nations in New York, titled Single Form. For her, the work represented the idea of the UN as a single symbolic body. My piece is a series of 12 photographs where I “analyze” her piece with my hands, re-building it in cardboard. So for this new commission outside Geneva I’m taking her sculpture apart into it’s 6 elements, each cast in concrete so it’s going to look a bit like stone but it’s clearly a heavy material. The pieces will be scattered around the site as if they could be ruins, like fractured columns from a Greek temple, or they could represent a stone-yard, where artifacts for some future utopian society are being carved. The piece is actually for an international high school, so that refers back to the UN.

The goal for me was to get the students interacting with their body with the piece. Obviously they will be sitting on it looking at their phones, but I wanted to have something that they would have to physically encounter in different ways and that related to the scale of their bodies. So sculpture and the body are becoming more and more important to me as another way to talk about architecture (through sculpture).

NV: So let’s talk about the other main subject in your work, which is abstraction: I think you are interested in the malleability of the meaning of an abstract form. Abstraction can come from nature and mathematics, yet now nature changes so fast that I wonder how abstraction from nature adapt to these shifts.

TG: The verb to abstract means to take something and turn it into something else, to extrude it from an original form. Often an artist will start off in figuration to then move into abstraction, like de Kooning or Calder. Then you have artists that work directly and formally from the imagination and it’s also called abstract work but it’s non-objective. I’m always working with forms that have resulted from processes of abstraction, almost always from pieces from the 50s and 60s. I’m specifically looking for forms that can’t be associated with natural figures, although Noguchi is somebody I’ve worked with a lot and developed the source code for what I call biomorphic modernism. It worked its way into design as well as becoming a simple stylistic tool.

What’s interesting to me in abstraction is that you arrive at a unique kind of self-contained form that takes on another meaning, that somehow can become a symbol for something, etc. The Hepworth sculpture, Single Form, that I have used in my work, is interesting because she designed it to symbolize unity. She associated this reading to the work , but the meaning has changed with time. And we have the US embassy in Havana, which is a box—it could be a minimalist sculpture. When you look at modern architecture and you break it down to its geometry it can always be read as minimalist, like a Donald Judd piece, and this is something I play with a lot.

NV: So if we speak from a temporal point of view, maybe you are drawn to the a-temporality or the anachronism that can be contained in these abstract forms?

TG: I guess I’m drawn to the flux.

NV: Yes, a temporal flux. I guess that is why I was thinking about nature before. What is nature nowadays? We know all these changes are happening in the natural world, like planetary computation and its material form, which we acknowledge but which we don’t necessarily see in a tangible way. Or like the Fordite mineral in Detroit –it is a mineral made out of fossilized layers of paint coming from the car factories. All this is nature now. So how does that affect current abstraction? The nature from which Hepworth and Noguchi were abstracting was probably way less corrupted than it is nowadays…

TG: Yes, it was the infinite. It’s funny because when we start talking about nature and the infinite I start thinking of the unconscious. Nature is a formal storehouse, it can be accessed and its elements can become templates for whole bodies of work. Or I can start searching in my own unconscious and extract forms. Maybe it’s the same thing? A piece like Free association which I’m showing in Mexico City at Labor this winter is made of forms brought out of my unconscious but almost always resembling forms like Hepworth, or Noguchi. In a way this is my source code, the sculpture from that period. When I think sculpture, that’s the kind of stuff that occurs.

NV: There’s this nice story of my friend Aurora who is an artist and a very bright person. Her father is an anthropologist, and he recounted in a text how little Aurora at age seven came to him and asked in awe: “Daddy, wouldn’t it be great to make “a sculpture of a sculpture”? When I asked her she said she of course did not even remember the event. But I though it was a great intuition about the idea of sculpture in general.

TG: That’s amazing. That is totally the root of everything. In my work, all the stuff I’ve done about display is about an object that represents itself and I’ve always seen that as the central problem of art. It’s like a thing that represents itself.

Interview conducted in Mexico City, December of 2015.

All images courtesy of the artist and LABOR, Mexico City.

Comments

There are no coments available.