Issue 16: Images Quiver in the Dark - Río São Francisco

Davi de Jesus do Nascimento, Beatriz Lemos

Reading time: 11 minutes

04.11.2019

Curator Beatriz Lemos speaks with artist Davi de Jesus Do Nascimento to highlight how that which moves through the body changes narrative and political concerns and generates alternative ways of experiencing memory through the realms of fantasy and imagination.

River bodies keep the secret of the waters and the scent of the earth. They know how to communicate with the enchanted beings of the forest, with the fish-people, with the seeds still inside the fruit. They paint stars on the bottom of canoes and carve carrancas.[1] Davi de Jesus Do Nascimento is a muddy river being, born in the city where fish leap from the water to battle the river’s current. A descendant of master carranqueiros[2] and the son of a fisherman and a librarian, Nascimento became an artist in order to heal his grief over his mother’s death. Since then, he has learned that his body is made of fear and rage.

Building on a negotiation between memory and fantasy, Nascimento’s work establishes a space of narrative delirium where he dedicates himself to constructing images through texts, photographs, and paintings. Davi comes from a people known as the Barranqueiros, who live in communities along the shores of the São Francisco River—one of the largest freshwater rivers in South America, popularly known as Velho Chico.

All of the cosmogony that exists along this major river form a symbolic part of our history. Afro-Indigenous spiritualities that insist on surviving in spite of their constant fading find new meaning through orality and imagination. Reimagining memories through images allows us to continually access our ancestry, and, in so doing, helps us to understand that our narratives are processes that cure and conserve existence.

Beatriz Lemos: When you told me that being barranqueiro means being born with clay-stained skin, I thought how it is that communities conceive and constitute themselves with their unique cosmovision and customs. Yours is a culture that follows the banks of the entire span of the São Francisco River. What does it mean for you to have been sculpted by that clay?

Davi de Jesus Do Nascimento: When I was born in 1997 in the splendor of Norte-Minero, I was baptized with the same name as my father, Davi de Jesus Do Nascimento. He was a fisherman, a carpenter, and a canoe-maker. I grew up learning to live with great respect for the rivers and knowing how to measure the excessive joy expressed in the current, along with the real need of bathing in the waters of the São Francisco. Every blessing is an immersion into the complexity of having your navel rooted in a freshwater current. When I think about what it means to have been sculpted from clay, the taste of fish fills my mouth. I believe that the ribeirinha diet contains the appropriate amount of clay from the riverbanks to maintain the earthiness of our insides, that which dies as people sink into carrion. I am a bixa[3] from the countryside who feels the weight of the river on her back. It is essential to be aware of the river’s resistance and of its death. Every day I arise with the responsibility of waking, preserving, or bringing back the river that resides inside each person.

The body that is not an offering is also a destroyed, shipwrecked body. It is always a ritual of water and delirium. My work is a cry.

BL: You come from a family that builds carrancas, which are mystical, wood-sculpted figureheads that protect boats. How does the sacred operate in your thinking about art?

DDJDN: Carrancas emerged along the Velho Chico at the start of the nineteenth century, when they were placed on prows of boats to protect fishermen, to lead the way, and to keep the caboclos[4] out of the water. Carrancas would shout three times to warn of a potential shipwreck. Halfway through the twentieth century, they began to disappear; they were removed from the front of canoes because they were associated with the devil. But instead of fully eradicating the practice of placing a figurehead at the prow, this movement led to its reproduction. The people adopted carrancas, placing them at the entrances of their homes as energycleansers. I come from a family of master carranqueiros—those who sculpt these sacred figures that are so important to us barranqueiros.

The sacred runs through my artistic work in a dimension beyond language. When I am producing work, it is important to feel in my efforts the strength of an experience rather than of an experiment. The mythical entities of the river are with me all the time and this allows me to continue building altars, cribs, waterbeds, and tranquility for my ancestors.

BL: Your work and writing lead us to a very specific place—memories of childhood and the beginning of adult life—so singular that they seem like fantasy and imagination. Do you see the construction of a fictional narrative as part of your production? How is the image born?

DDJDN: My relationship to writing came from my mother, who was a librarian. In life, she shared with me books by authors who wrote about fish like Manoel de Barros and Guimarães Rosa, authors who today are some of my references. I love them. I will never forget the day when she gave me a book by Orides Fontela, or the moment my writing came to life with Kadosh,[5] a book of prose by the Brazilian writer Hilda Hilst. Three months ago, looking through papers at home, I discovered that my mother had kept my umbilical cord wrapped in gauze along with a letter from 2000 about the São Francisco River crying for life and asking for help for the barranqueira people. My mother responded to the call of the river and drowned in 2013, months after achieving her dream of graduating with a degree in pedagogy at the age of 45. I have also been influenced by my deceased great-grandfather, João das Queimadas, who was a sailor, writer, and steamship carpenter. The bodies of water and downpours that cut flush with the stone surface are bridges that connect all the mediums I work with, which let me swim across them. I recognize that I use fiction to speak my truths and as a strategy to protect the secrets I have inherited, mixing the limits of dreams and reality with the same centennial lucidity as my great-grandmother, Chica. She shouted: “You have to give the hook and not the fish.” The image is born on a patio in front of the port and grows on top of it, in mourning, channeled in the varicose veins of my mother’s legs. Every time the mystery demands a moment of silence—like a bridge—from me—the river is shallow and runs between the rocks.

BL: This imaginary repertoire is very much present in your production, whether in photography, painting, drawing, objects, or installation. When did you perceive these secrets taking the forms they do? How did they come to their relationships with materiality and languages?

DDJDN: It is at the moment when I see them hold up a collective mirror—which is to say, when the river dwellers identify with what I am building. And that implies dialect, temperature, color, scent, and textures: the displacement of the territory of belonging. The autonomy of being able to name and create my languages seduces me. I gather the scent and warmth to live and I pick up fragments and objects while I walk the streets of my city. Rotten parts that come together and become complete objects, bleeding sculptures. Talking about life within the stench is like building altars for daily prayer and cribs in a room filled with discomfort. I try to create a dialogue that can move the other as an interlocutor in the exorcism of pain. My actions contain the despair and the crowdedness that the surface of things demands to live through bodies. The body that is not an offering is also a destroyed, shipwrecked body. It is always a ritual of water and delirium. My work is a cry. A cry for the life of the São Francisco River, for the Piraporense del Norte-Mineiro people, and for my own life.

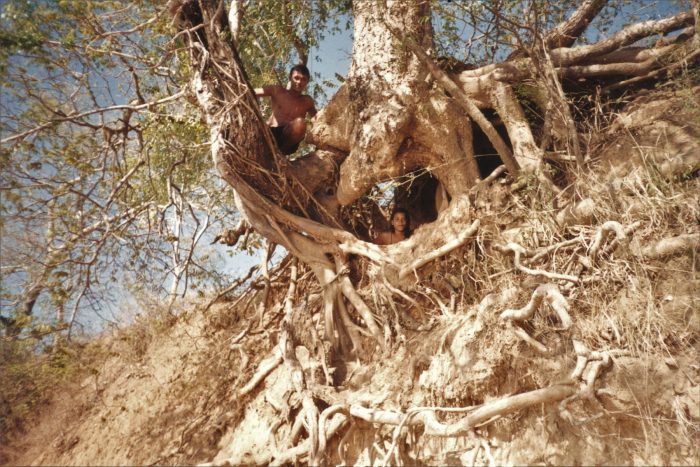

BL: Your family is very present in your work; it ignites your production, which draws from the death of your mother, your association with your brother, who is responsible for the beautiful photographs taken in Pirapora; and your father, who constantly participates in the conception of your work, not to mention the relatives and neighbors who are portrayed in your collection of family photos. How do you feed this dialogue in collectivity?

DDJDN: My research is alive because I have the approval of my families, who function as the essential thermometer for every bridge of work I build. I am excited about the confidence my father has in me to care for our memories. I believe in mutual growth, which includes strengthening affective relationships with my relatives. It is a network, a network woven to catch abundant fish. Knowing where we come from in order to have the certainty that we will return to the bottom of the river. We are killing our rivers. We are killing ourselves.

BL: The collection of family photographs presents your relatives’ perspective on community life, but it is also a valuable document concerning the changes suffered by the river, such as falling water levels and deforestation along the river’s shores. How do these changes affect bodies?

DDJDN: Four years ago, after the death of my mother, I inherited the family’s film photographs, taken between the eighties and early two-thousands. Records of camping, fishing, and events on patios with the scent of wet earth—it is an archive my relatives established based on a mutual, spontaneous need to produce memory. I usually say that these photographs are stored water, a patch of extended memories. As I was curating the photos, I started to restore them and write about the experience of being the child of the turbulent waters of a mythical river. In the span of three years, Vale—a Brazilian multinational mining company—was responsible for two of the greatest social and environmental tragedies in Brazil, in Mariana and Brumadinho. The latter took place on January 25, 2019. The Córrego do Feijão dam in Brumadinho in the state of Minas Gerais broke, killing more than 250 people, many animals, and all the surrounding vegetation, while also contaminating the Paraopeba River. As soon as this second crime took place, my father called me and said: “I am trying not to think of the crime so that I do not get sick.” But I, who am also a river body, know that there is no avoiding it. To a certain extent, it is fear that runs through us. The São Francisco River is starting to get contaminated and it smells of minerals. It is important to state that this comes as no surprise. We were concerned with the problems of river pollution even before any “new” news reached the big city. Destruction, transposition, drought, and the broken dike. And yet, there is a lack of sensibility, an inability to understand that the river is a living being, that it can even die, but that it can also kill. The São Francisco River came to me in a dream one day. It said that this whole flood is for us to bathe in. We are approaching the largest collective swim in history. Bathing with a cuia in the world’s first mirror, the water in which we see our reflection.

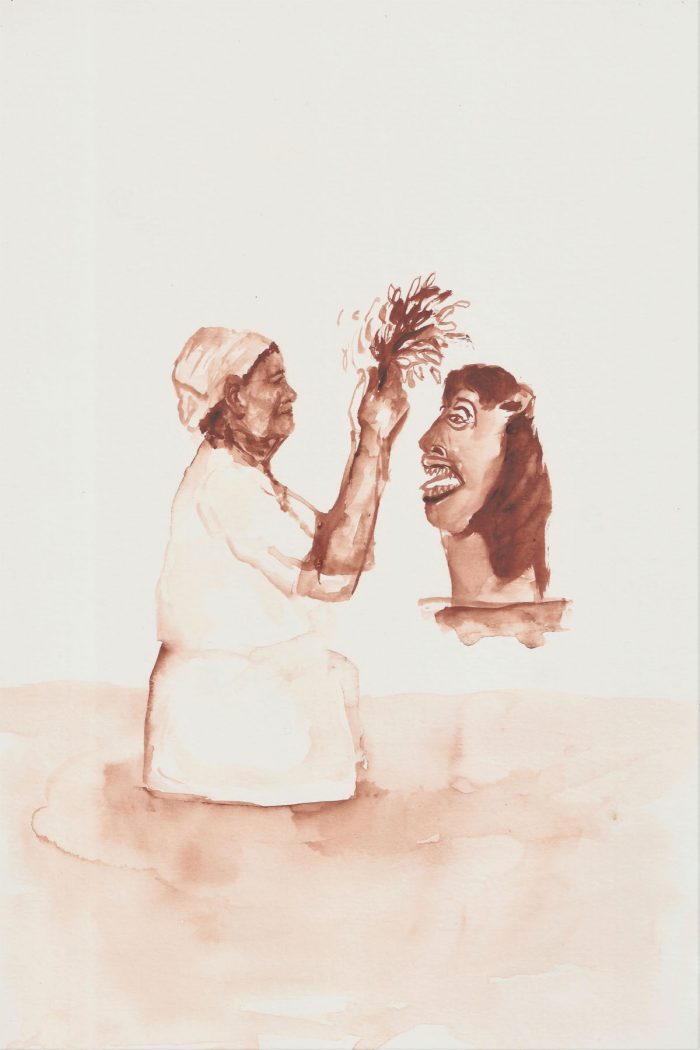

BL: Was the watercolor painting festa do sol [Sun Festival] a sign of this collective swim? How was it produced?

DDJDN: I always think that that which is to come has already been traced out. I do not believe in coincidences. Once I dreamt that I was listening to a conversation between two canoeiros. In the dream, they spoke of Valdir, a fisherman who died trying to bring his boat’s candle to his chest. After a time, my father told me that the men who rowed the boats in our family have a callus on their chest, which is indicative of their profession. This is what happens in festa do sol. I painted it before realizing that my father had lost many friends fishing. He went out to fish with his friends and one time one of them drowned. These are relationships that eschew the obvious and come to me through narrative. The collective swim may also be a collective death. The river kills and so does the boat. They are not the same chests, yet they are chests nonetheless.

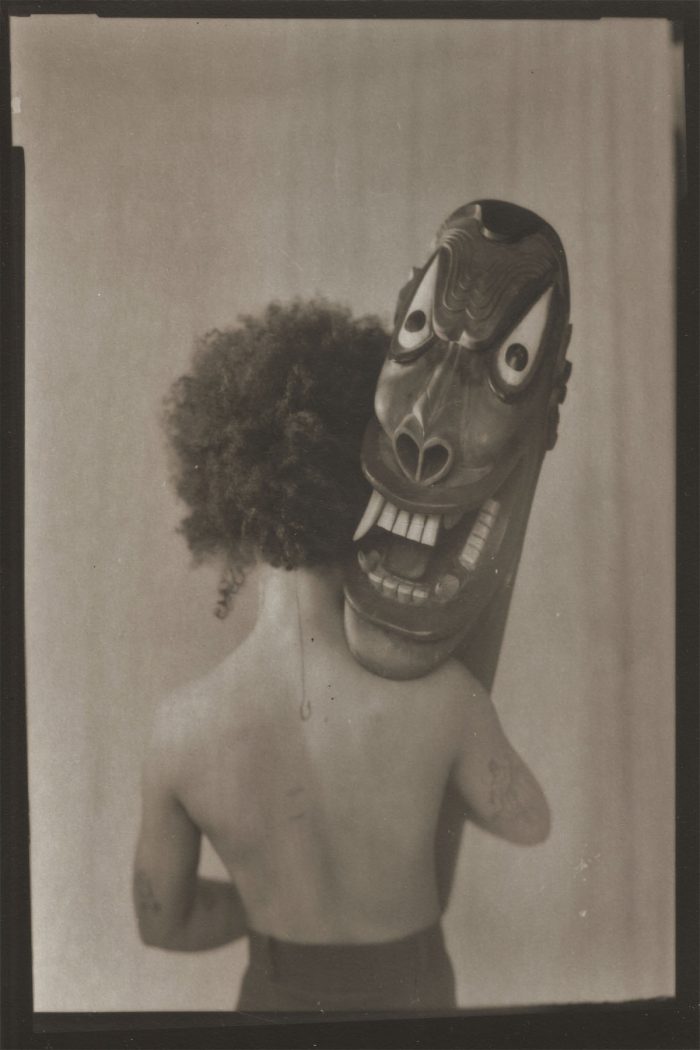

BL: One of your most recent works involved carrying a 45-pound carranca on your back for six months, day and night. Is this action, among other works, a way of reconnecting to the river?

DDJDN: Yes. To return to and connect with the river and the barranqueiro’s method of accepting daily events. It is a reminder of my responsibility to be a body that carries the weight of the river on its back, a responsibility that grows as I move further away geographically from where I was raised. I understood, after a period of carrying the carranca on my back, that I was in a state of penitence, and, at the same time, working towards a transformation in order to understand that our times do not require me to carry a carranca. Rather, I am a carranca. It was very powerful to see that people have an affective relationship with the carranca. Many people recognize it, others are afraid of it. There is always a lot of curiosity. People ask if I sell or carve carrancas. I had to justify myself all the time. At that time, I felt the importance of having the heavy object attached to my body, like a child. A form of creating that absorbs quebranto. [6] I am blessed.

A carranca is a sculpture with a human or animal form, made of wood and placed at the prow of the boats that navigate the São Francisco River.

Translator’s note: Carranquieros are the people who carve carrancas.

Translator’s note: A pejorative Brazilian term, it can be translated as “fag.”

In addition to being a term used to refer to indigenous people in Brazil, caboclo also refers to people of both white and indigenous ancestry.

Comments

There are no coments available.