From the work of Tiago Carneiro da Cunha, Fernanda Brenner reflects on parody as an element with the ability to subvert the clichés of Brazilian and Latin American exoticism.

I write this text in Lisbon, in an apartment overlooking the Tagus River. From here I look directly at the point where the navy of Pedro Alvares Cabral left in search of a new route to “The Indies”, placing me in the perspective of the Portuguese navigators who arrived at the Brazilian coast. Every historical narrative is always the story of different points of view. Brazil is far, Tom Jobim said, in a mixture of relief and disdain, but far from where?

Sometime in the 1930s, the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa described Europe as the extended body of a woman: one of her elbows —the right— nailed to England, and the other —the left— withdrawn in the Italian peninsula, and Portugal, the face, turned towards the immensity of what at another time was called the “dark sea.” This patriotic ode of Pessoa’s rescues the rhetoric of the “Age of Discovery” to exalt a new conception of the world, proposed by that small strip of land on the edge of Europe. The poem “O dos Castelos” was published in 1934 in the book Mensagem, the only one that the poet published in his life, in a complex esoteric and nationalist outburst launched just after the constitution of the authoritarian Estado Novo of Salazar.

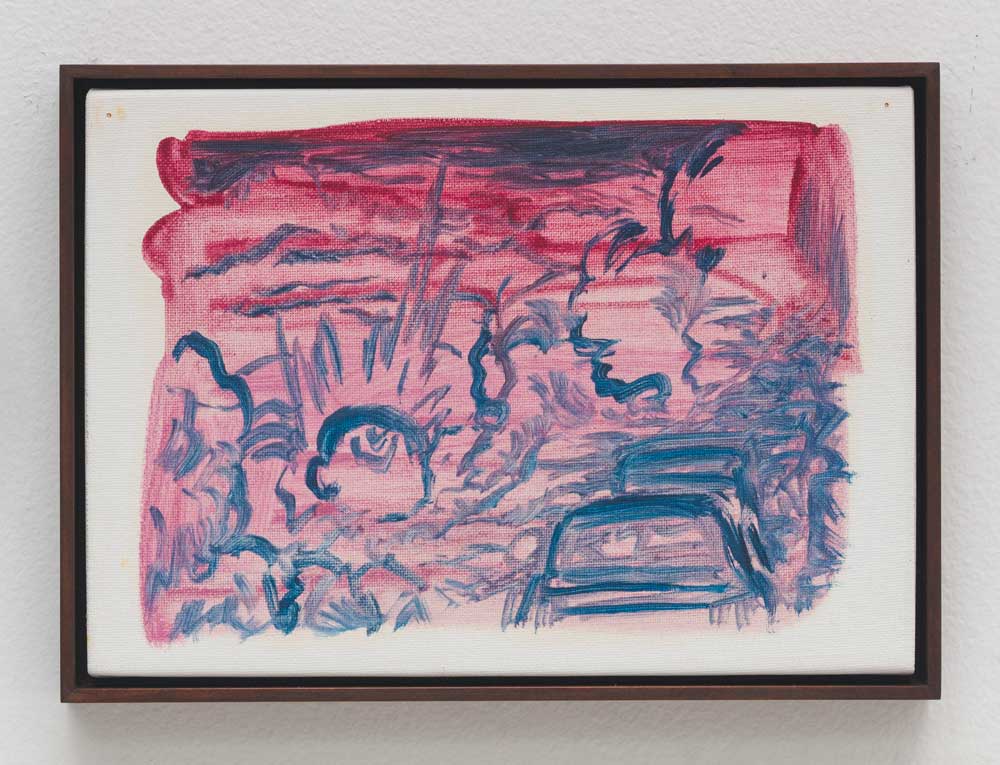

I spent a good time trying to draw on the map of Europe the woman described by Pessoa, and in that exercise of figuration I found myself trying to overlap Tiago Carneiro da Cunha’s painting Gostosa II with what I saw in Google Maps. The small painting is part of a series of recent works which the artist made for his last exhibition in São Paulo Traffic from Hell / Transit through Hell at Galeria Fortes D’Aloia Gabriel in 2016. The artist, best known for his three-dimensional production in ceramics and resin, presented for the first time his experiences with oil painting.

Gostosa II is a mulatto woman lying face down on a sunny beach that could be interpreted as “typical of the tropics.” However, what supposedly qualifies the beach as tropical is more the presence of the sensual woman, wearing a tiny bikini, than any definite spatial reference. The fast brushstrokes set out the scenario are nothing but variations of cerulean blue that can suggest both a summer resort in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean Sea. Fernando Pessoa describes the look of the Europe-woman as “sphinx-like and fatal” and the caricatured woman of the painting has her back arched and rests on her elbows in a posture similar to the Egyptian sphinx. The two images (the mulatto of Carneiro da Cunha and the “cartographic woman” of Pessoa) have in common the fact that they are emblems of idealizations: the first embodies an assumed libidinous behavior of the tropics and the second personifies the image of a new possible helm for Europe between the wars, also through the archetype of the female body. The nationalist exaltation of the 1930s gave what it gave in Europe, and I am not sure that today the outward look towards Brazil has moved far enough away from the reductive images, the condescension, and the exoticism with which it was always treated.

Tiago Carneiro da Cunha, unlike the allegorical image of Fernando Pessoa, deliberately chooses stereotyped images (the hottie, the Latin American…) as triggers to test processes and techniques that he is fond of, in a dynamic closer to the child who scribbles characters in her/his school notebook, than that of the professional artist who plans a project to be executed. The artist’s ongoing Transit through Hell blends medias and references (he overlaps the hell of Dante and São Paulo’s traffic jam; Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi is turned into a Brazilian politician and Cycladic art meets Candomblé in his practice) to fulfill his analytical —almost anthropological— interest for what could be described as ‘common sense’. The social sphere and the figure of the artist, as much as clay and oil paint, are the breeding ground for the infernal characters created by the artist.

By returning to circulation these versions of clichés in a stylized painting or sculptural format, free exercise and doodles come to operate as objects loaded with form and content, marketable, susceptible to criticism and interpretations, and inscribed with themes and identifiable categories from the field of contemporary art. What interests the artist is precisely that marshy territory between the spontaneous and calculated that permeates all artistic creation and its disclosure. According to Tiago Carneiro da Cunha, an artist is never impartial. Each work (or artist) in circulation must carry the potential to advance our relationship with art itself, preserving the confinement of expressiveness while critically recognizing (and why not with humor?) the circuit in which it is inscribed.

In the work of Tiago Carneiro da Cunha everything is always melting, even when it’s not. A mud monster holds a lit candle, its amorphous body resembling a sitting gorilla, carrying a long draped blanket and never reaching a definite appearance. Made in polychrome faience and painted in enamel, the sculpture accompanies the melting of the wax through a splash and multicolored coating. There is a certain caustic cruelty in transforming a character that supposedly belongs to the repertoire of horror films into a chandelier; a domesticated monster on duty, half butler, half furnishing. The artist is constantly driven towards this thin line between the seductive and the macabre. His characters are tragicomic, they go beyond comic books or B-movies, unfolding into nuanced and complex figures, which are capable of provoking repulsion and at the same time captivating the viewer. In this dichotomy we recognize a familiar reality: the pain and delight of the Third World; the crestfallen Latin American is also a flower vase. [1] The artist’s choice of discomfort and bewilderment comes close to what philosopher Giorgio Agamben called “serious parody” in his book Profanations (2007), while simultaneously persisting and mocking his own obsessions and anguish.

For the Italian philosopher, parody is the symmetrical opposite of fiction, insofar as all parody has in common the dependence on an existing model (which is transformed from seriousness into comedy) and on the need to conserve the formal elements of such a model to which new and incongruent contents are indexed. Understanding that the ordering force of the model and norm are “deactivated” due to the fact that they are repeated in an ironic way, Agamben describes the genre as follows: “Unlike fiction, parody does not call into question the reality of its object; indeed, this object is so intolerably real for parody that it becomes necessary to keep it at a distance. To fiction’s ‘as if,’ parody opposes its drastic ‘this is too much’ (or ‘as if not’). Thus, if fiction defines the essence of literature, parody holds itself, so to speak, on the threshold of literature, stubbornly suspended between reality and fiction, between word and thing.” There is something in the liquefied universe of Carneiro da Cunha that is inscribed in the heart of the parody, his work does not become fiction, but neither is it an explicit social critique.

The fantasy territory inhabited by Tiago Carneiro da Cunha is the result of an intentional sublimation of a context that is intolerably real.

By evoking with humor what is canonical or unspeakable, the artist brings us closer to elements of our society which are so flagrant and traumatic that they challenge reason.

When news is so close to the fantastic narrative, those muddy monsters and treacherous devils —that shed the eroticization of the tropical man, the high social inequality in Brazil, the misogyny, fundamentalism, or lack of urban planning of their cloaks— no longer seem so absurd.

The works of Tiago Carneiro da Cunha are always portable and small-scale, as if they were always ready to be collected and transported. With the urgency and eloquence of a peddler, who lives between selling gracefully and packing her/his smuggled goods when the police arrive, the artist chooses the most traditional and stagnant techniques and forms of art history (oil painting and pottery) to remind us about the transience of our own condition. A charming skull wearing a green cloak carries a sickle and an hourglass while waiting for something in an idyllic setting. The painting A Hora II (The Hour II) once again relies on the immediate identification of the cliché, death personified in the reaper skull, to later provoke a mix of feelings. The skull is inviting, it seems to offer a solution to the absurdity of existence while suggesting an agreement with the inexorable: all death is the end of a cycle.

Following the example of the characters of Tiago Carneiro da Cunha, I suggest that we return to believing in mystery, to once again gather forces and develop new methods to reinvent, instead of conquer, the dark sea that we created ourselves.

Comments

There are no coments available.