Issue 18: Of Passageways and Portals - Chile Mexico

Antonia González Alarcón, Sandra Sanchez

Reading time: 13 minutes

27.07.2020

By way of correspondence, artist Antonia González Alarcón and art critic Sandra Sánchez share their views on the possibility of approaching artistic practice and the act of looking that mediates knowledge from affections.

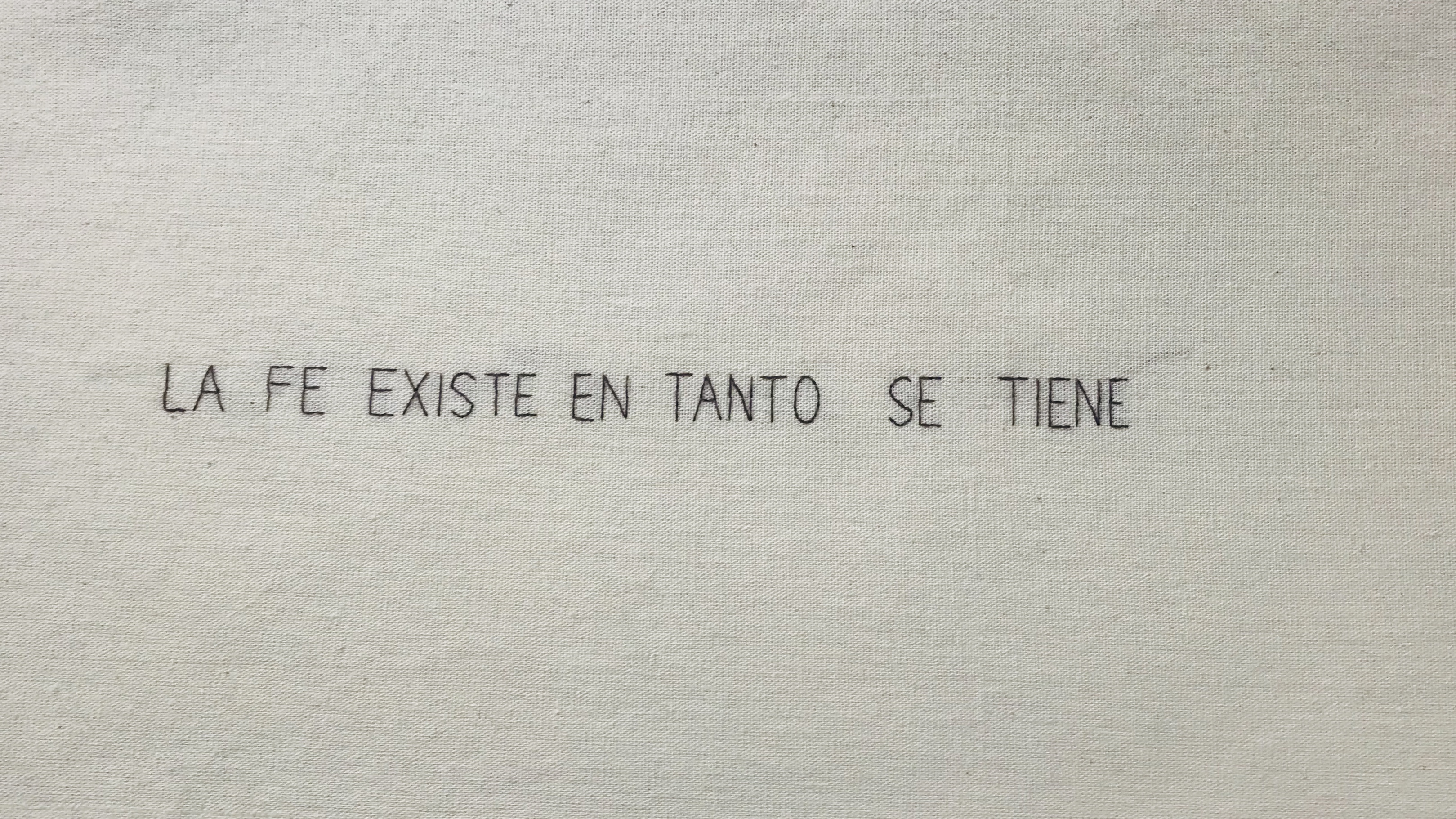

Sandra Sánchez, Acto de escritura 2, 2020. Imagen cortesía de la artista

Hi, Antonia.

I write these words to try to get the conversation going. I feel that this text, which is still private, already has a public feel to it, which makes it even more complicated to get started. So, if you’ll allow me, I’m going to tell our (so far) hypothetical readers what it’s all about. You’ll get to tell them too.

Antonia and I have been talking about a path that runs through her theoretical-artistic production: sensation, emotion, feeling. Since we’re still in a quite modern aesthetic system, it is usually thought that the feelings we have about a work of art only concern the individual and personal, without being relevant for someone else. In the theoretical sphere, sensations and feelings are repressed and displaced in favor of a logical-conceptual context that is incumbent on all of us, for the former can be objectified and introduced into the public sphere as competing knowledge.

I have the impression that this conversation began when Antonia gave me the opportunity to read her thesis (written for completion of her degree at La Esmeralda), which deals with the affections and feelings when producing or viewing a work. When reading it, I felt the problem close at hand, for I am also concerned about the polyvalence of aesthetics: their revolutionary as well as fascist effects (Terry Eagleton, The Ideology of the Aesthetic).

I am making these notes because it is important for me to tell you that I do not believe that emotions occupy a sphere of metaphysical spontaneity, rather I think that in a conscious and unconscious way emotions are linked to our own ideological background and to a pedagogy that we have socio-culturally adopted starting with the nucleus of upbringing and the familiar. In this respect, I remember the book by Roland Barthes entitled A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments. In it, he takes a journey through common places that, however, when one personally experiences them, they feel unique.

A hug,

Sandra

***

Dear Sandra,

At times I find it amusing to return to this topic: it seems unrealistic to think that we still live according to paradigms of opposing dualities, where we separate emotion from reason. As you rightly point out, we’re still in a modern aesthetic way of thinking and I believe that modernity is characterized by separation.

When I wrote my thesis El puente [The Bridge], my research wanted to cover two personal concerns: that of the artist as a producer of theory and the ideas I had absorbed during my artistic education on creating from the affective. It was an urgent need to enunciate from theoretical writing–being too many the times that we read from theoreticians that do not produce–with the idea to pronounce myself an artist, with said parameters for my companions and myself. That’s why it was so natural and valuable to share that text with you; the very fact that we are writing today is, for me, a sign that this is something that needs to be felt/thought[1] more.

This leads me to feel/think myself not as a creator, but as an art observer as well. From there I have learned to create and admire. When I find myself in front of a piece, it evokes emotions of all shades; for me, it’s nonsense to pretend that this is not important. This becomes more relevant as I am an artist and understand that my pieces exist with and in relation to others and, therefore, to the emotions linked to their unique experiences.

Sandra Sánchez, Acto de escritura 3, 2020. Imagen cortesía de la artista

When we become aware of this, the affective networks that accompany a work of art become visible, those which you say we only share with our closest accomplices. It’s like dark matter: it’s there, creating tension, even if it’s intimate.

In her essay Los niños perdidos [The Lost Children], Valeria Luiselli mentions that “it’s never inspiration that pushes anyone to tell a story, but rather a combination of anger and clarity.” Many artworks have been created at this intersection between emotion and name, and are transformed into an artwork when that translation process occurs. What is interesting about this is when another meets such a piece and identifies there the clarity that his emotion lacked. I think as much as I feel, even though they are different languages, they meet and interweave to create the piece that matters to me.

You’ll tell me how you feel/think about this.

A hug as well,

Antonia.

***

Antonia!

I am very excited about the embroidery workshop you are going to offer; I think that learning from an artist is something I have rarely experienced.

Regarding what you tell me, I’d like to ask you if you are concerned by or propose to produce the conceptual, material, and spatial (exhibition) conditions to convey a specific emotion. That is, do you think that something about your identity, your political position, or your own name is at stake when attempting to convey a particular feeling and/or emotion? What happens if that fails?

I would like you to be our compass when introducing readers to these issues, taking as a starting point your exhibition Dónde crecen los claveles [Where Carnations Grow] (2019), shown at LOOT Gallery.

I also think that, in your thesis, as an art observer, you realize how several other artists have been concerned with this same aspect; perhaps you could tell us a little more about your particular pantheon and your view on them.

Have a nice night,

Sandra

***

Sandra, dear,

I’m also very excited about the workshop. I think the best decisions I’ve made lately were to take this initiative and to be there in front of people and share a space with them, even if it’s online.

Trying to get people to feel specific things when confronted with a work of art is tremendously difficult. When I am working on a project, I understand that there is an emotion that guides me and that many will be able to capture it from the way I am creating it. Rather, in putting forward an idea, what I intend is to create an affective space where everyone can connect between their experience and mine. As if it were a constellation of ideas that they may connect as they wish.

It’s always a coin flip; finally, there’s no universal recipe for reaching everyone in an emotional way and it’s not what I’m looking for either. The exhibition Dónde crecen los claveles is a great example of this. In this project, I developed an investigation around memory and mourning, guided mainly by the idea of emotional recovery after Pinochet’s military dictatorship in Chile. Not having lived in a dictatorship, as a Chilean, my life has always been permeated by it for those who lived it relive it all the time. What I have experienced is a second-hand pain or an inherited pain.

I decided to embrace it through memory and mourning because it is what belongs to me and what I know. That’s my business. In a way, this went beyond the dictatorship: it was about any process of trauma, this tension between memory and oblivion. I know that because I have lived it. What I was looking for in this exhibition, more than provoking a specific emotion, was to provoke a series of sensations that would develop in this context: What mourning have I experienced? What kind of grief am I going through? Now, how can I relate that to someone who lived through the Chilean dictatorship? If there was one specific thing I sought to evoke, it was empathy.

Thinking about artists who have worked with similar dynamics, Raúl Zurita comes to mind. He is a Chilean artist and poet, who built a whole universe of sensations and language for the post-dictatorship process that many Chileans still have in their bodies. His piece Ni pena ni miedo [No shame No fear]—a text intervention in the 3 km long Atacama Desert—is very powerful because something that has characterized Chilean culture is emotional numbness, avoidance, and self-induced amnesia.

What Mexican artists do you think relate to this subject? And on the other hand, do you think this fits within the concept of relational art?

Also, I would love to ask you about any experience of your own that you have had that you may relate to these affective ideas within the art world. Is this something that happens to you often?

A hug,

Antonia

***

Antonia, 🙂

I’ll confess: I haven’t started the embroidery exercises. I hope to give myself time this afternoon. My apartment is very hot, it gets a lot of sunlight and I have to go to my bedroom for four to five hours during the day, the coolest place. There I do nothing but reading and sleeping.

In answering your question, I find that the work being done by illustrators (like you) approximates feelings and ideas that come from the personal to address a public moment. Lately, I have thought that illustration (as a medium and as a strategy) does not have much museum value because its discourse is too specific, too literal. It seems that this operation is not so pricey for museums and galleries, we can recognize there a symptom of institutional desire.

I think it’s relevant that illustration carries out the proposal of the technical reproducibility presented at the beginning of the last century by authors like Walter Benjamin. Although still somewhat alien to contemporary art, illustration and its reproduction are very well received by the public on social networks. There, producers and spectators like, look, share, and form common spaces, based on shared feelings, affections, and struggles.

I keep thinking about what led us to value the discourse on individual feelings. As I said at the beginning, I think it is important to subject one’s own feelings and sensations to criticism, for it can be seen as natural. However, to subject the feeling to criticism does not mean that we should cancel it or omit it because this would have the effect of relegating it to a metaphysics of the present and immediacy.

I’m taking a course by a cinema critic. In the first session, something came up that made me think about this conversation: the sensitivity for a poetic filmography—with complex audiovisual rhetoric—on an apparently simple narrative. Which seems to favor the former because it opens the door to a kind of active spectator. I think that your position, which I can refer to as a critical theory, is interesting: to leave spaces in which the viewer can elaborate so that they do not become alienated. However, I also see proposition’s trap: the astonishment before a complex poetics that can come to camouflage a certain idea (old but, sometimes, operative, even unconscious) of high culture.

Sandra Sánchez, Acto de escritura 1, 2020. Imagen cortesía de la artista

This same year I have witnessed, more than once, people boasting a kind of superiority for juggling and knowing certain signs and concepts that, in their naivety, they still believe to be universal and/or totalitarian in operation. Anyway, I don’t think that encrypting the codes or not is the core of the problem. Rather, I think that culturally we have taken for granted that encryption is more complex than communicating or feeling; moreover, the latter is considered more susceptible to manipulation than round, objective concepts. How tricky!

It is already rumored that this means of artistic production is criticized for using people for the purposes of the artist or for generating momentary changes and then “abandoning” communities. I believe that both judgments are valid, although they do not exhaust the relevance of the pieces. Personally, I don’t believe in paradise, any of it; so, I celebrate projects that change (even temporarily) life’s rhythm. I must say that we would have to analyze each work case by case to comment on them with the care they deserve: care is also to submit to criticism, not to agree, and, even so, to maintain a dialogue: to sustain the feelings of frustration in order to try to direct us towards other developments (probably also failed). Art history is not the history everything, fortunately.

As you can see, I have a lot of mixed feelings.

A kiss,

Sandra

P.S.: Thank you for telling us about your relationship with memory and how it is strained by feelings. By the way, it is time to close our conversation, not because of a lack of desire, but because of the word limit. Here’s a blank page for one more entry. I’m happy to have talked publicly with you on this subject.

***

Sandra dear,

During the embroidery workshop, I talked with several girls about the relationship between embroidery and room temperature. It seems that embroidering when the weather is hot is a bodily contradiction. I find it amusing to think that I couldn’t embroider as much if I lived on the beach or that my most effective embroidery times have been during the winter or in the poles.

This thing you mention, the reproducibility of illustration, is something that is implemented now more than ever. Nowadays it can be totally immaterial, supported by other virtual elements such as followers and so on. The illustration falls into a more naive place with respect to that, which I do not think of as a failure at all: it is rather something that allows us to connect with it from another place.

What amazes me about illustration and about doing illustration is that I see how quickly people appropriate its narratives: they print them, they tattoo them, they share them, they comment on them. It creates a bridge with those who see or consume illustration. Moreover, illustrators have the agency of feeling—translating—publishing in a very direct way, without mediations; as immediate as the appropriation that their creations live. This breaks every formality of the art market and the museum.

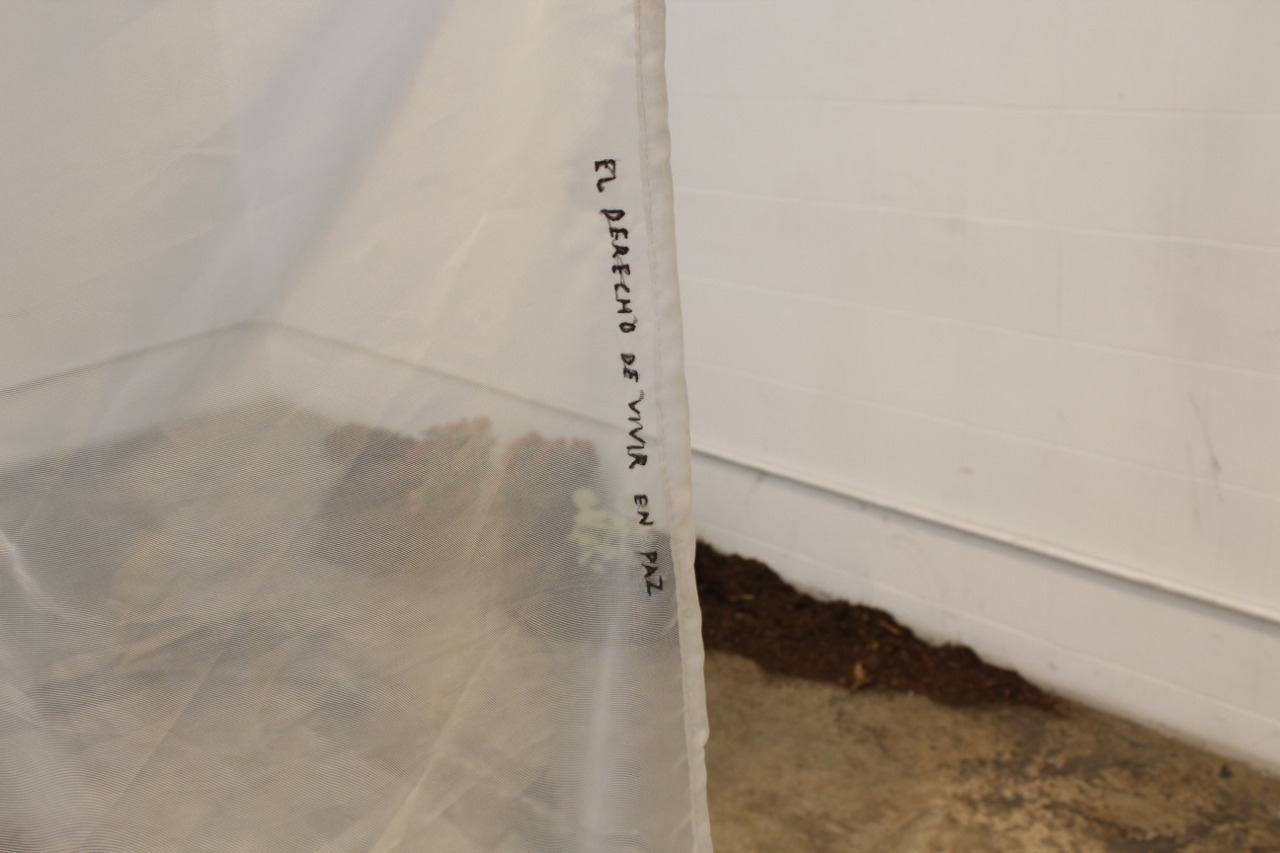

Antonia González Alarcón, Decálogo de luto. X - silencio, 2019. Imagen cortesía de la artista

How nice that you just mention this contraposition between the narrative and the poetic in cinema. I don’t know if you know Jonas Mekas, a Lithuanian-American filmmaker who happens to be one of my favorites. He unites the idea of poetics with a giant emotional simplicity, the taste for beauty, and happiness. These concepts seem to be contrasted with the “interesting” or “intellectual” in artistic discourses, so it is unusual to see them incorporated into them. What fascinates me about Mekas is that his exploration is born out of his personal pain and an autobiographical rift. This intersection, where simplicity and emotion manifest themselves through beauty and poetry in no way diminishes it, but rather creates a complex and captivating imagery. I’m telling you all this because I think that in cinema, we constantly come across narratives that show the affective or emotional as something crude and the poetic or abstract as high culture, when there are thousands of examples that weave both together in wonderful ways. Saying all this, I read and recognize myself thinking and crossed by emotion, all at the same time.

Something that resonates with me from our conversation is a belief in the possibility, without conclusions, without walling up concepts or closing off ideas. Thank you for opening this space, which feels so refreshing in these contexts where we build knowledge and art.

A hug,

Antonia

***

This text is part of a series of collaborations between the artist Antonia González Alarcón and art critic Sandra Sánchez. In November they will write simultaneously for Diario Públicco IG @diariopublicco. We thank Terremoto for giving us a warm welcome.

Editor’s note: It’s important to trace the genealogies of thought behind words that burst into the imagination from other vocabularies, in order to recognize that there are diverse sources of knowledge beyond academia and Western-centric ways of thinking. To feel/think is, then, a word that describes an ethic of the Zapatista pluriverse where reason moves as the central axis of daily experience to make room for the feelings that cross the body as a seed of experiences that will allow “a world where many worlds fit.”

Comments

There are no coments available.