10.10.2016

Martha Kirszenbaum and Myriam Ben Salah navigate shifting East/West political contexts, gender and religious identities, and curatorial practices versus personal experiences.

Mymiam Ben Salah: You run Fahrenheit, a space that is based in Los Angeles and has strong ties with France and the French artistic scene. In that context, what brought you to invite someone–yours truly–to conceive an exhibition dealing with Middle Eastern and North African concerns?

Martha Kirszenbaum: Fahrenheit is indeed an exhibition space and residency program focused on artists curators, and writers connected to France, but the space is also establishing a connection to international practices. It is founded by FLAX (France Los Angeles Exchange), a private non-profit foundation based in L.A. aiming to promote French culture in the city. It seemed fundamental to me to structure the program in the context of post-colonial thinking, the social realities of immigration in France, and the process of the integration of Arab minorities there. This driving impulse was subject to a feeling of increased urgency in 2015, after the terrorist attacks in Paris raised so many questions about France’s Arabic culture and history. But here again, I was willing to expand it to an international context, and to invite someone who, just as you, would be able to articulate the micro and the macro, building a narrative that might include artists from the Middle East, North Africa, and the Diaspora, and could foster a conversation about immigration. You are a young female curator who grew up in Tunisia and moved to Paris to study and later work. How do you negotiate these personal identities and experiences in your curatorial practice?

MBS: Sincerely, I have never felt like an Arab or identified as a Tunisian, or as a woman for that matter! Not that I reject any of those things of course, they’re part of me. But I never defined myself primarily as such and it was never a prism that I looked at things through. An “Arab” in France is much more a social status than an ethnicity. Coming from a rather modest but still “bourgeois” background in Tunisia I wasn’t identified as “beur” [nickname for French from Northern African descent]. So I always felt like a rootless cosmopolitan with very little knowledge about identity politics. As an adult, my curatorial practice went on to explore other interests that were not linked to my cultural “essence.” And then the Charlie Hebdo attacks happened in France and suddenly I “became” Arab in the eyes of others. I was asked to speak up for “my community,” to condemn the acts of “my peers,” and it would have been perfect if I could wear T-shirts reading “Not in My Name.” I thought it was insane and I have to say it shook me to the core. I realized you can’t escape identity, and it became an interesting subject of study in and of itself. Actually my residency in L.A. at Fahrenheit opened up a seemingly never-ending stream of interrogations and a renewed interest in the anxieties surrounding identity because here in the US it clearly underpins lots of social issues. You grew up in France where the idea of Laïcité (secularism) is at the very core of citizenship and is interpreted in a very singular way, and we had numerous conversations about how the situation is different in the US. I want to ask; how do you negotiate your interest in Arabic culture and how has your work explored the religious persecution of Arabic peoples?

MK: I have to say that my take on laicity is not only shaped by growing up in France, but also by the fact that my parents are immigrants from Poland and they grew up in a communist country and were raised by very secular parents. My grandpa would regularly destroy his building’s mezuzah with a hammer in Israel (laughs). I tend to believe that religion divides people and oppress women, whether it’s Catholicism, Islam, or Judaism. Obviously, saying this in the US, a country where people are obsessed with race and religion, sounds provocative. I agree with the French principle that religion should remain a private matter, yet I think that the law restricting veils and burkinis on public beaches is discriminatory nonsense that stigmatizes French Muslim women. A formative experience for me was my trip to Iran last year. Although it is an Islamic Republic with many restrictions based on religious rules, I realized that people are still able to to remain independent both inside their homes, and in their general behavior in public, and in their thinking. Paradoxically, although people might live in a country ruled by religion, not all conform to Islamic religious tradition. Iranian culture is also Persian, and very different from traditional Arabic culture. In this sense, I think that there is a plurality in performing a religious identity in Middle-Eastern culture.

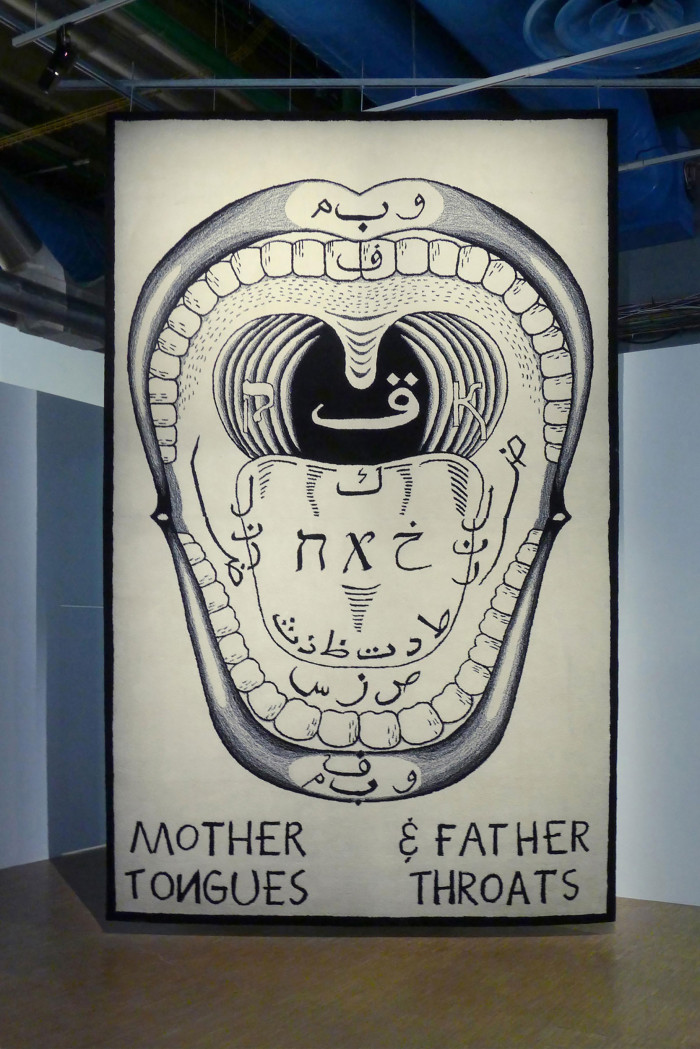

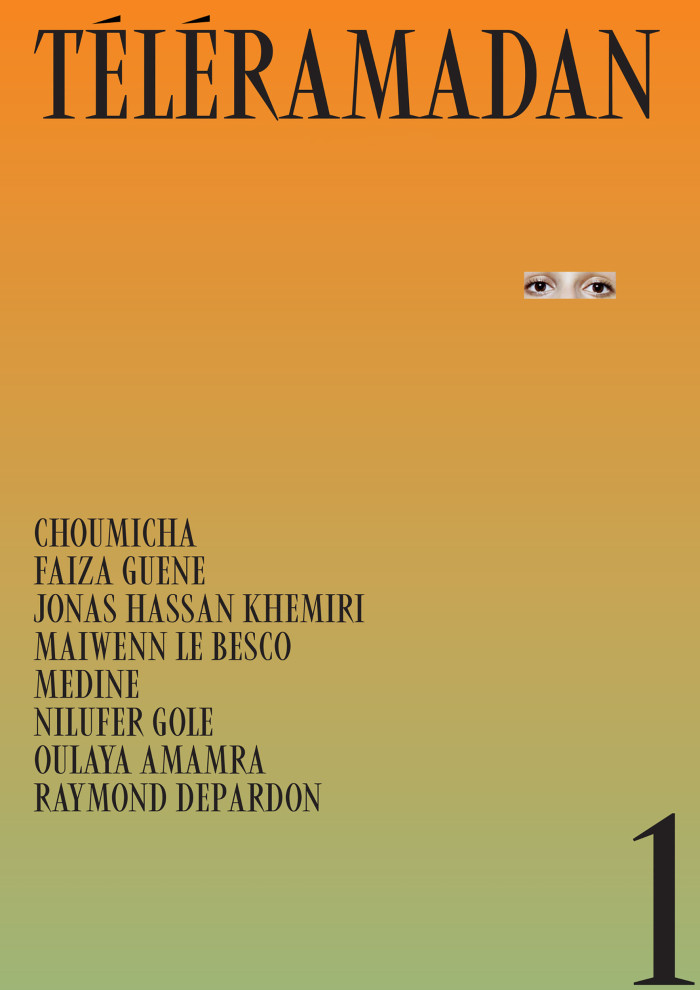

When I look at your exhibition, and the screenings we put together, not so many of the artists directly deal with religion, but they instead look more at the intersections of culture and society. I believe that these are in fact the central issues. Why a woman born in a French banlieue would decide to wear a burqa is a question of culture, and the social tolerance of cultural difference, as much as it is a question of religion. In France, the integration of Arab communities has become an urgent measure in the past few months that has been heightened by a tense political context punctuated by terrorist attacks, and the burkini polemic. You decided to include the magazine Téléramandan in the exhibition, as well as a review about Arab culture in France started by Mehdi Meklat, Badroudine Saïd Abdallah and Mouloud Achour, who want to shift the narrative about French Muslim communities. Can you talk more about this choice and what is at stake here?

MBS: In her article “The Social Turn: Collaboration and its Discontent” published in Artforum’s February 2006 issue, art critic Claire Bishop states “the typical western viewer seems condemned to view young Arabs either as victims or as medieval fundamentalists,” describing the media’s selective production and dissemination of images from the Middle East. I think it is precisely the same situation right now in France although the post-colonial ghost makes the situation quite specific. Right now, young Arabs in France are either demonized as potential terrorists or victimized as submissive individuals (a.k.a. women). Téléramadan bifurcates from these dialectics and takes the identity and religious experience outside of the « other »’s gaze. It gives the floor back to individuals, the same ones I was referring to before, the ones burdened by issues bigger than themselves. Téléramadan slips from the current « secular rage » (to paraphrase the artist collective Slavs and Tatars who updated Charles de Foucauld’s expression). It is a sharp and clever reaction to the ambient rhetorical imprecision and media humiliation surrounding Islam in France. It is born out of frustration and it is radical in its commitment to beauty and poetry. And more than anything else, it is unapologetic. That’s a core thing for me. Arabs in France have been apologizing too much.

You have a certain interest and knowledge in regard to Middle Eastern popular culture, especially in terms of music and moving images. Where did that come from?

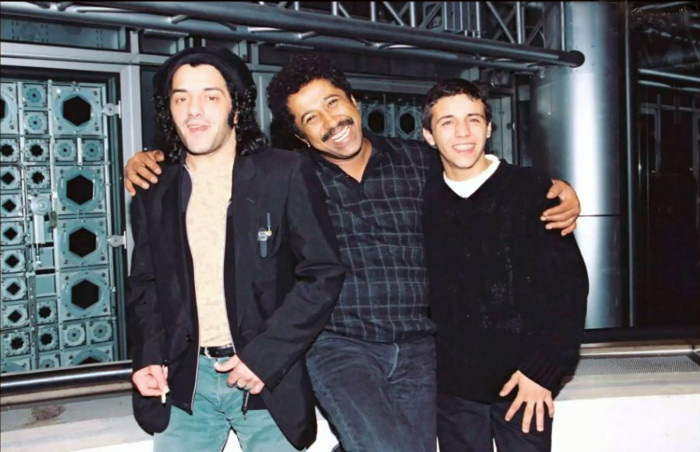

MK: I grew up in the suburbs of Paris in the late 1980s and 1990s, a moment when suburban French popular culture incorporated a lot of Northern African elements, particularly in music. Many raï musicians moved to France in the 1990s fleeing violent years of radical Islamist terrorism in Algeria. In France in the 1990s, there wasn’t a party, a restaurant, or a radio show without a raï hit playing. The success in France of French-Algerian musicians such as Khaled, Cheb Mami and Faudel is a rare example of the blending of North African culture with French popular culture. I remember this element of pop culture very vividly. This might also be because of my personal experience, if not double life, as a belly dancer. After a trip to Morocco when I was 16, I started to belly dance in a company in Versailles, and then regularly performed in restaurants, cabarets, weddings, and other functions for the fun and the money. As a young student I would regularly belly dance in Paris or sometimes abroad, and my iPod would blast Sonic Youth, Fairuz, post-punk and Egyptian cabaret tracks with no transitions. I also discovered Egyptian cinema at this period, and got really hooked on Arabic movies from the 1940-60s. Thinking back now, I realize how lucky I was to grow up in a country where it didn’t matter whether you were Christian, Jewish, or Muslim, and that a young dancer with a Jewish surname could hit the dance-floor of Arabic weddings in full costume. Recently, after the attacks in France, several articles in the foreign press mentioned that ISIS wants to target precisely this grey zone, where people from different cultures and backgrounds live together and in peace. This is the France I grew up in, and this multiculturalism definitely shaped my vision of the world and how I envision my curatorial practice.

MBS: Would you have invited me to organize this exhibition in France–where the paradigm of identity politics is quite controversial within curatorial practices?

MK: Actually yes I would, and I only wish I could! What is interesting in working in a place like Los Angeles, is that on the one hand, I feel very empowered to talk about issues related to race and gender, but at the same time, I quickly realized how obsessed American society is with these questions, to a level that leads to exasperating political correctness. On the other side of the spectrum, in France, first of all if you’re a young woman in the arts, you don’t have access to a powerful voice (although I believe our generation is going to change this), and indeed, identity politics is a difficult prism to engage with, because the core idea of republicanism and equality acts as a steamroller for differences and particularities. I think it would be fascinating to present this exhibition in France, as it would raise totally dissimilar questions and would be interpreted very differently. In this sense, I think it was a brilliant idea to include Téléramandan in the exhibition. One of the main intentions at the Fahrenheit show is to deconstruct the stereotypes of the representation of the Middle East through the prism of violence, war, terrorism, and suffering, and to examine artists’ practices that deal with humor, irony, détournement, and popular culture. How did this shift come to you?

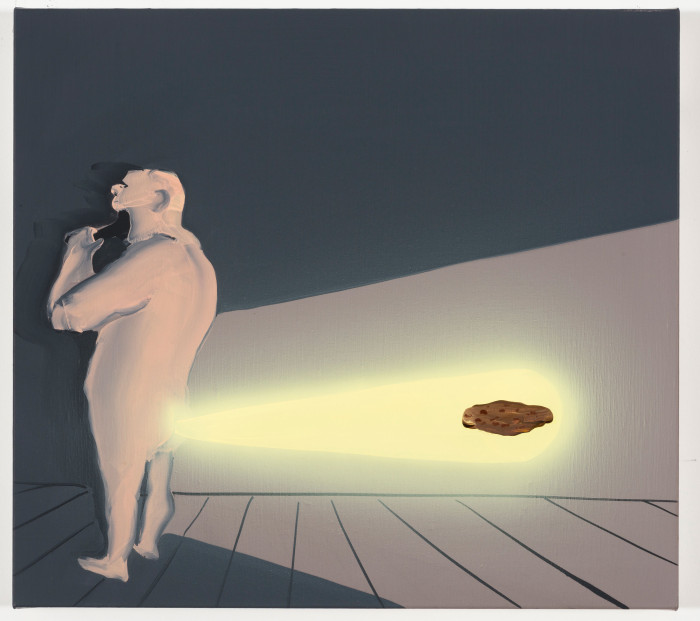

MBS: I guess I’ve always been fascinated and saddened by how a region with such a rich cultural legacy could be looked at only through the prisms of failure and conflict. I grew up in Tunisia where my grandfather was involved in politics and banished from the country for more than a decade during Ben Ali’s dictatorship. Besides, half of my family lived in Algeria, a country that was marked by a terrible civil war in the 1990s, led by the Armed Islamic Group. So I loosely experienced some of the political turmoil there, but I quickly realized that the media’s representations of those situations that the world subsequently received had nothing to do with everyday life. And that’s what interests me: the daily and the mundane. Even in times of war, people live, laugh, have dinner, and make love. And I am bothered by how representations of countries and their political situations bleed onto how individuals are perceived. The actual thinking that led to this exhibition began in a moment a few years ago when I was watching a BBC report on a wedding singer from the Gaza Strip who had won the Arab Idol contest. BBC reported that the city hadn’t seen celebrations or such outpouring of emotion since the end of the last conflict with Israel.

They were broadcasting fireworks, middle-aged men dancing the Palestinian dabke in the streets and groups of youths in cars cheering the name of the singer. The sight was quite unusual for general television, telling a diverging account of current events from what is usually reported of Gaza, but also Egypt, Syria, and Tunisia. I felt at that moment that in the end, in the face of pop culture, we are all equal. It was an interesting subject to explore through the works of contemporary artists. I was already a fan and diligent reader of Bidoun magazine, which after 9/11 had started to carve a path for contemporary art within the loosely defined region of the Middle East with a perspective that feels irreverent, very often funny, surprising, and almost always personal. There’s a new generation of artists shifting away from the preconceptions about the Middle East and the conflict narratives expected from them.

MK: During a conversation at Kadist Foundation in San Francisco last summer, you mentioned that the generation of artists you invited for a form of “vernacular disorientalism” marks the exhibition. Can you elaborate this concept and explain how it is relevant to your project?

MBS: This expression referred to a certain type of artistic production coming from the Middle East and its diaspora. I think there are two battles to be fought: the one of media stereotypes, but also the one of artistic standardization. Moroccan scholar Mohammed Rachidi coined the term, “tacit commission” to define the western gaze that conditions artists from the Middle East and North Africa to perform authenticity through narrow aesthetic formulas, traumatic back stories, and melodrama. I feel that a new generation of artists who grew up online is breaking these paths welcoming in an era of “digital cosmopolitanism.” Their art is not rootless though, it is specific of a time and place but it doesn’t speak to the West and doesn’t feed the western normative gaze. For me that’s what “vernacular disorientalism” means.

Comments

There are no coments available.