10.01.2022

Curator Diego Ventura Pac-Coyoy shares reflections on the bicentennial celebration of independence in Central America to raise questions about the relationship of cultural work with that narrative, inviting a reimagination of the idea of “nation” that the Central American community forms through the arts.

I wake up

(without you)

in the country that sleeps.

My grandmother and my father woke up early

in this place where

the fool is still

fool

and the thief, thief.

My grandmother and my father are dead,

so is my country.

-Carolina Escobar Sarti[1]

History is an erosion. At best, a wound. It is a constant, changing event. History through hegemony is a timeless and totally predominant social fact and does not obey its changing and evolving nature. So far, in Central America, hegemonic history is the work of establishing a single (official) version of the facts, it is a framework that has been going on for 200 years. A crystallization[2] of this nature cannot be removed without organization and the activation of defense mechanisms.

The establishment of these ideas and their subsequent crystallization as a social fact in the collective imaginary requires a condensation[3] of diverse actors that contribute to the stability or fall of these ideas. In its broadest sense, collectivity turns out to be this condensation. We can note three types of collectivity: a hegemonic collectivity, which brings together actors for the preservation of discourse, dynamics, and lines of thought convenient to their power; a counter-hegemonic collectivity, which, in the fragile Latin American democracies, evidences, denounces, points out, and counterbalances the previous collective; and finally, a collective shaped by precarious circumstances[4] with little or no approach to the dynamics of power and counter-power of the two aforementioned collectives.[5]

In the first group we can include important economic sectors with a long tradition; conservative groups, religious leaders, the army, the government, businessmen, and others. In the second, non-governmental organizations, research institutes, study centers, universities, intellectuals, organized movements of Indigenous people, workers, students, and others. And in the last group, people who may belong to both but, as mentioned above, due to circumstances dictated mostly by the dominant group, are not directly involved in the playing field even though such circumstances affect their daily lives in a direct way, a condition that has been normalized so as not to be perceived directly.

In this line of thought, it is appropriate to note, then, the social fact that we are interested in discussing at this time: the independence of Central America. And together with this event, a phenomenon arising from it, the celebration of the 200th anniversary of the signing of independence.[6]

II

“The body hurts the wound…”

-Carolina Sarti Escobar[7]

According to the ideas on collectivities mentioned above, where is art located? What is the role of the artistic community in this phenomenon? Where are the individual actors located? Where are the institutions located?

In view of the celebration of the bicentennial, which is what motivates this text, we must remember the context of art in recent years. Through it we have made counter-hegemonic proposals around anti-racism, equality, depatriarchalization, decolonization, feminisms; through public denunciation we have articulated against bullying, harassment, and other forms of violence, which in many cases are witnessed.

These proposals have been worked on by both individual and collective artists and have been accepted by galleries, biennials, institutions for international cooperation, and private initiatives. In themselves, they constitute a public manifesto for the construction of possibilities around what we understand as a “nation”.

In relation to the proposals and the places hosting them, we can also identify discursive lines. From my particular point of view, living, working, and producing from Guatemala, the problematization of the bicentennial through the artistic practices in this territory has a strong dissident presence,[8] something that I don’t see in the rest of the region. I believe this is due to the strong and manifest coexistence of nations of Indigenous people[9] in this territory, in comparison with the national projects of El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. It is worth asking who or what can be seen and heard in political terms, as well as when, where, for whom, and in what way.

If the bicentennial celebration confirmed anything, it is the need to abandon the monolith of the nation that homogenizes differences and does not take into account the conflicting co-existence of hegemonic and counter-hegemonic collectives and those in precarious circumstances. It is crucial to abandon the logic of citizenship—a Western-centric social contract—that celebrates the bicentennial in relation to discursive lines of democratic triumphalism, which itself exploits needs that are certainly urgent in terms of human rights. Consequently, by assuming the values of the social contract of the democratic nation-state, human rights such as the “right to culture” are normalized as universal, functioning as an instrument of ideologization in defense of individualism that does not consider the demands made by popular struggles for communal dignity, struggles based on cultural traditions other than the Western one. In other words, the bicentennial imaginary articulates a democratic narrative of national unity—specific to Guatemala in our case—that allows nation-states to appropriate and exploit the cultures, languages, sacred sites, and territories of Indigenous people to guarantee the “right to culture” of the citizenry. For example, the Guatemalan Ministry of Culture and Sports does not allow us to manage ceremonial sites; everything is manage by the state. Another example is the issue of territoriality: in the name of Guatemala’s progress, large swathes of Indigenous peoples’ territory are expropriated to give them to mining and hydroelectric concessions, etc.

In the context of Central America and specifically in Guatemala,, multiple Indigenous community organizations, the Mayan-descendant and conscious community, articulate demands calling for the cessation of the violence described above. The demands of these organizations have on many occasions been addressed by artists/thinkers in our local context[10] which, at a regional level, provide paths for answering the questions mentioned at the beginning of this section. And with that, more questions.

What is culture? What is identity?, What is ideology?[11]

Beyond definitions, which are well known in this context, I am interested in bringing these words to discussion in order to problematize the idea of “interculturality”—the interaction between cultures—which forms the deep interrelationship and the weight of the artistic exercise in our region, not only in terms of the daily life of the artist/collective/institution, but also in terms of its specific relationship with the nation-state, precisely with the bicentennial commemoration.

Ideology permeates culture.

Identity is defined through rituals, expressions, practices, and reflections which are or aren’t permitted by ideology. Therefore, culture is an expression of both. It is at this point where it’s worth addressing cultural expressions and their context since, finally, what is manifested and named through such expressions is a diagnosis of the thinking, needs, demands, or complicity of the multiplicity happening in this time/space.

III

When I was born

two tears were placed

in my eyes

so that I could see

the size of my people’s pain.

—Humberto Akabal

With regard to this celebration, it is worth mentioning what has been seen in the visual arts sector. To the previous questions, mainly about the location of the cultural actors and institutions in the collectives, a glance is enough to locate them.

In the field of curatorship and visual arts, it is important to identify which nation we respond to. As a social conglomerate (whether we call them consumers, workers, or voters) we swing between two extremes according to the script dictated by the hegemonic apparatus. At one extreme is the state, national identity, or patriotic values, effectively used in governmental discourse to call for national unity. On the other, we see the differentiations that are constantly stressed through aspiration and the market. Both are the discourse of the dominant economic group. They are two arms of the same entity. So, as a curator, what do I respond to? In principle, it is important to identify that my work, as part of the art system, is based on prestige, which is surplus value, the same which is used for speculation. According to this individualistic order,

is it possible to imagine collectivity in my work? Does the community exercise mean something to me as a curator?

Community curatorship makes it possible to address, respond to, and present issues that go beyond a personal vision in order to reach reflections around possible joint imaginations of solutions. What are we imagining then in the exhibitions around the bicentennial?

In Guatemala, from a governmental point of view, the publicity apparatus spoke of national unity and patriotic values. Institutional images were unified with logos created for the occasion. This was the case of the Carlos Merida National Museum of Modern Art, which maintained a prudent scheme, hosting external events and a large retrospective exhibition.

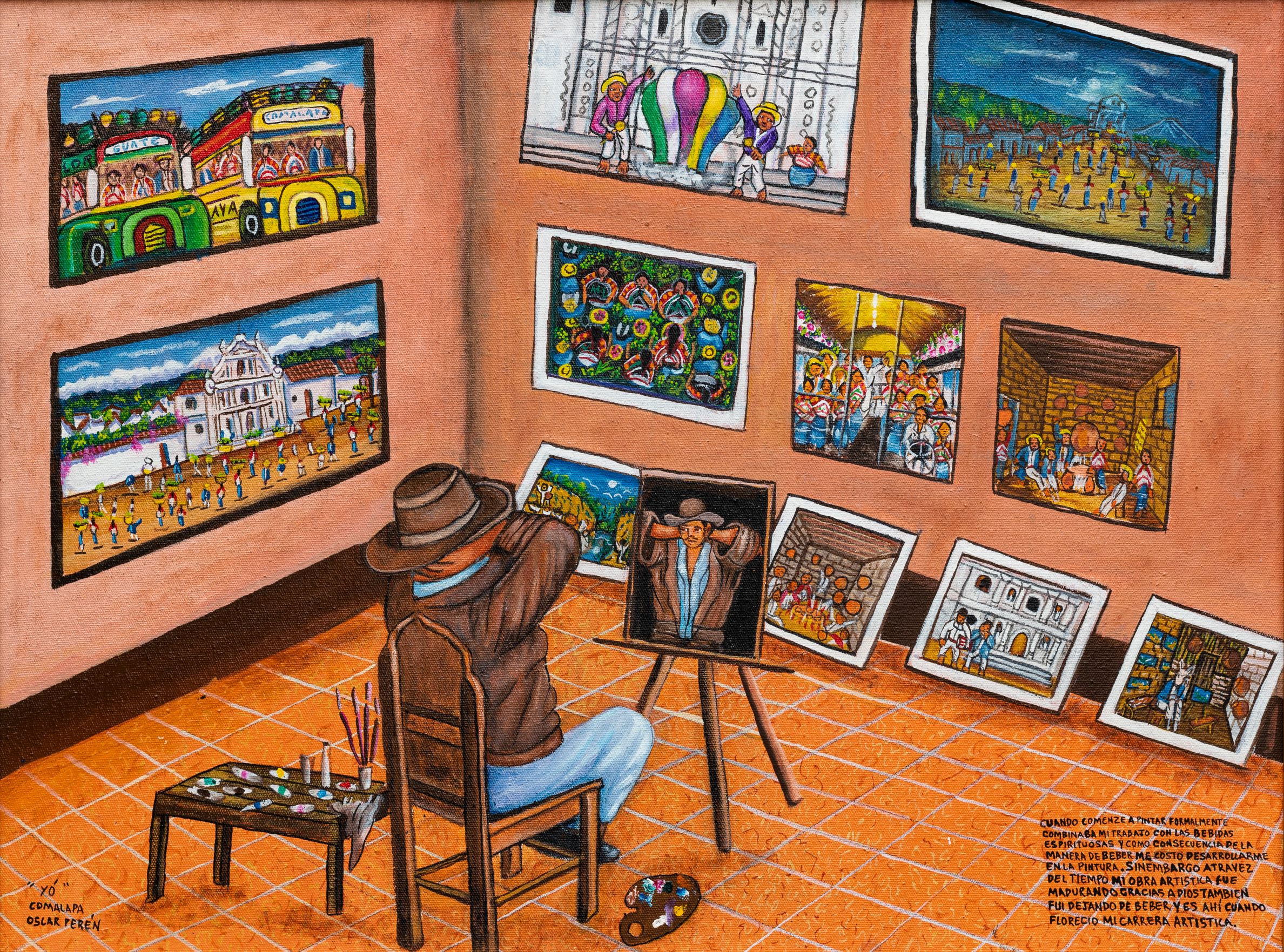

From the private sector, there were two exhibitions. First, the UNIS-Rozas Botrán Museum presented, over three years, a script dedicated to the celebration of the republic and the bicentennial framed in the official history. On the other hand, the Paiz Foundation presented two different dissident narratives. The most recent edition of the Paiz Art Biennial, entitled perdidos. en medio. juntos [lost. in the middle. together], articulates a curatorial discourse in relation to colonial violence within a North-South dynamic that addresses the problems of the Global South (including Central America). The second exhibition, Antes de ser ya éramos [Before being we already were]—made up of pieces from Paiz Foundation’s own collection together with the collection of Fondo de la Imagen, Palabra y Pensamiento Ventura Puac-Coyoy [Ventura Puac-Coyoy Collection of Image, Word, and Thought], a collection that is located in a non-central, or rather an uncommon place for collecting—projects the history and implications of the “homeland” from the point of view of the Indigenous peoples.

Outside this territory, in Costa Rica, the Cubo Negro exhibition curated by Daniel Soto Morúa was organized. It addresses problems at the regional level and makes grievances visible to the governments in power. It speaks about territories, cultural identity, gender, violence, migration, and hegemony. The exhibition brings together creators from all over the isthmus and counts on the collaboration of various actors in the region: TEOR/éTica, YES Contemporary (El Salvador), Costa Rica Film Festival, and even the Museum of Modern Art of Medellín (Colombia). The themes proposed and the curatorship lay these points out on the table and not only call on us to reflect but also allow us to see the way in which these issues affect our daily life and practice.

From Panama, the government built a monument for the occasion in Coclé. So far, rejection from the cultural sector has predominated, perhaps because its history is more linked to Colombia than to the rest of Central America in relation to Spain. Even so, one of the narratives that stands out to me most is the cultural centralization of Panama. It seems that all artistic and cultural life happens in, from, and for the city. The activities, research, and exhibitions account for the intimate relationship between art and the city. This is also part of the construction of the collective ideology of that country, and it is in turn a statement of how culture is understood and for whom.

In this sector at the regional level, there is a relationship between the evidence of the problems in contemporary life and the razing of the colonial policies that survive in each nation-state. In any case, the real celebration is to disrupt the universalization of memory, thus allowing counter-narratives that, from these territories, recognize how complicated it is to forget the wound. Finally, it shaped our lives and the visions we have of our country and our futures, respectively.

What is the possibility of futures? Have we imagined those futures as an artistic community? What are the future interactions between hegemonic, counter-hegemonic groups, and those shaped by precarious circumstances like? How will our artistic practices participate in those interactions? How will interculturality arise in the future? In the present, from my reality and from my craft, I question if I fully recognize myself and if I understand the place I occupy in relation to my responsibility in this collective, which ends up being one of the many pieces that make up the apparatus of the nation-state. What awareness do I have of myself? Where I come from, it is also imperative to recognize my own actions in this construction. How many times have I acted as if I were allowed or being done a favor to “be”? Do I act as an element of multiculturalism where I fill a quota of inclusion?

Do I expose the real problems of my community?

Do I use my identity and insert it in a discourse of multiculturalism for my own benefit? Am I a token or an element of folklore?

Carolina Escobar Sarti, Te devuelvo las llaves (Guatemala: F&G Editores, 2010).

According to Nico Poulantzas, the material crystallization of a social phenomenon occurs if its permanence becomes a social fact accepted by the collective even if the social forces are in opposition.

In the same vein as Poulantzas’ ideas, there is a correlation of forces and a set of social relations occurring within an economic (capitalist) system where everyone is part of the game and has a role on the board. The social facts that take place on this board are established when all these actors, forces, and relations “condense” and result in the facts remaining, whatever their motivations or objectives in the social-economic-political plane, as long as they give character to the game.

Circumstances that can be summarized as impoverishment, access to poor education or no access to education, and working conditions that force alienation.

Perhaps the classification of these collectivities is more of a response to a definition of classes, but at this moment in Latin American life and after the pandemic phenomenon, socioeconomic mobility is not completely defined and economic thinking, as well as class consciousness, often does not respond to the class reality of individuals.

It has been 200 years since the independence of the provinces of the Captaincy General of Guatemala. The signing of the act on September 15, 1821, which put an end to Spanish colonial rule, gave rise to the current states of Guatemala, El Salvador, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua.

Carolina Escobar Sarti, Te devuelvo las llaves (Guatemala: F&G Editores, 2010).

By “dissident presence” I refer to the recognition of dissident bodies, levels of autonomy of Indigenous peoples, collectives organized post armed conflict, and other actors that are a counterweight in the local political and social sphere.

The ways of life, beliefs, community, and economic dynamics of Indigenous peoples are, in general terms, contrary to the plans of the Latin American nation-states, mainly because they oppose the unifying banners that are the main elements of the domination of hegemonic history.

I am referring to Jacinta Xon, Rosa Chávez, Chumilkaj Nicho, Sandra Xinico, Negma Coy, Anny Ventura, Marilyn Boror, Kaypa Tzikin, Niebla Púrpura (Luis Morales Rodriguez), and Edgar Esquit, among many others.

Mario Roberto Morales, Conceptos básicos de la interculturalidad https://mariorobertomorales.info/recursos-educativos/interculturalidad/

Comments

There are no coments available.