Issue 20: How Are You? - performance transfeminismo

Reading time: 11 minutes

17.05.2021

Artist and researcher Liz Misterio interviews artist Yolanda Benalba about two of her recent artworks that expand on transfeminist ethics making way for collective listening and political organization of sexual and gender dissidence.

LIZ MISTERIO (LM): In the video piece Randy, Midori, Rojita, by focusing on the words and experiences of sex workers, you twist the morbid and hypersexualized gaze that art and the media reproduce about them. How did you come to this approach?

YOLANDA BENALBA (YB): As you mention, I was interested in questioning the myths and images that exist around sex workers both socially and in the artistic medium. From our first conversations I felt a lot of admiration for their political agency and all the struggles they embody in their profession and activism.

In terms of bodily autonomy and emancipation, prostitutes are the perfect conjuncture. We all sell our workforce but prostitutes, independently and autonomously, manage to dislocate the power relations and domination of wage labor.

They define market prices, schedules, logic, relationships, roles, and so on. I am not saying that it’s easy or that we have to idealize it. On the contrary, many lose their lives while exposing their bodies. That is why we have to join their struggle so that they can have access to the workers’ rights and human rights that other labor sectors enjoy.

LM: Let’s get something straight: we are talking about sex work and not prostitution. As a movement, these women are fighting to be recognized as autonomous workers within a framework of rights, in order to have access to health services, housing, retirement savings, safe and dignified work environments, among other benefits and protections that Mexican law offers to workers in other sectors. Prostitution is a stigma-laden concept that does not take into account the conditions in which it’s exercised, since it does not differentiate between those who work autonomously and voluntarily, and those who are there as a result of human trafficking, thus restricting the demands of autonomous workers while fostering the helplessness of those who are victims of trafficking. From this clarification, I would like to continue asking you how you approach care when working with them and their life stories? What limits or discomforts did you encounter in the process?

LM: What does the collective body of sex workers tell us about the structural inequities faced by working women in Mexico?

YB: The experiences shared by Randy, Midori, and Rojita portray not only sex workers but other workers in the Mexican context. What mother, just like Rojita, has not considered changing jobs to be able to combine work and parenting? What woman does not reflect, as Randy does, about time management and life with the working conditions we have in this country? What worker does not demand labor rights and a legal framework that protects her, as Midori rightly mentions, so that anyone has the choice to work as they prefer? These are key points in determining that sex work is work, without it being punitive. Furthermore, putting the labor adversities faced by feminized bodies on the table opens the door to empathizing and tuning into the struggle of sex workers.

Faced with an institution that systematically refuses to meet the demands of a large number of students who have been assaulted or feel unsafe in its facilities, the piece El grito, which was housed at the Museo Universitario de Ciencias y Artes (MUCA), opens a dialogic space from which the collective body practices somatic listening to the people who are directly and daily affected by the patriarchal culture that has allowed the normalization of sexual and gender violence in classrooms and society in general. How did the group of performers you worked on this project form?

YB: I understand screaming as a tool of protest. To shout comes from the Latin quiritare: a call for help, to raise the volume of one’s voice, or to give cries for help. The genesis of quiritare is associated with the word quirites, who were those considered “citizens” in ancient Rome. Quiritare is a legal and political verb, closely linked to public expression and citizenship. So screaming is literally demanding civil rights; that is the power of screaming.

LM: The artistic device, in this case, serves as an infiltration in the museum into the discourse of protest and collective pain in the face of injustice. It makes way for collective listening and political organization of sexual and gender dissidence by providing a space for their demands to resonate. I would like to know in what way these emotions are transmuted or healed through performance?

LM: How did you structure the symbolic and formal elements of the piece?

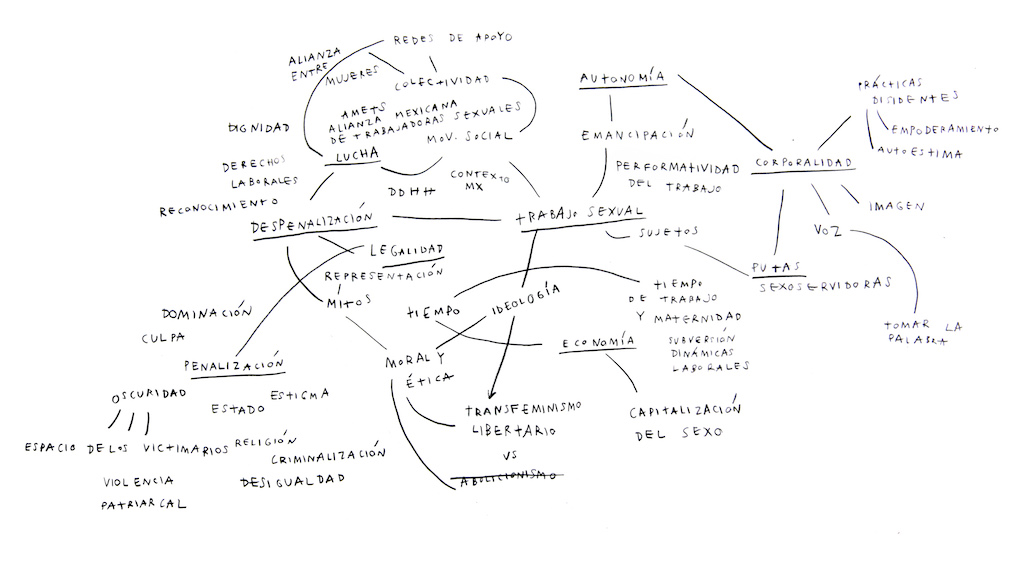

YB: The installation is a meeting space that we activate weekly to weave networks, draw our shared body, and detonate our joint cry. It’s composed of different performative elements such as the overalls worn by the performers, a blackboard with notes that we updated after each meeting with the resolutions and exercises carried out, a banner that accompanied our actions under the slogan quiritare, benches that were moved according to our needs, and a circular mat, 8 meters in diameter, that defines the meeting space for screaming.

LM: In these projects, the voice and the sounds emitted by the bodies are more important than the movements or actions of the participants. What is the importance of letting the voices of people who academia and the art world have historically banned from speaking for themselves ring out in exhibition spaces?

YB: I like to imagine that my latest projects draw a transparent megaphone in space and that this scaffolding allows for the sharing of narratives and stories whose voices belong to the political agents that defend such counter-hegemonic narratives. On the other hand, we continually see in academic and artistic contexts proposals that expropriate and swallow up the voices of other communities and struggles. The reality is that we are already here: the whores, the trans, the queers, the fat, the Blacks, the disability community, etc.; we inhabit these spaces. However, the institutions turn a deaf ear and continue to silence and marginalize us. Therefore, it is not only important that voices resonate but also that bodies are presented. For example, in the experience of El grito, it was very pleasant to scream and run through the museum; it was a collective disruption of a usually sterile space.

The process of the exhibition was interrupted by the pandemic: the university closed its doors at the end of March 2020, the students were forced to abandon their takeovers of the faculties, the UNAM Biennial was unceremoniously dismantled, and the last performance of El grito in which the participants would join their voices in a crescendo of denunciations did not take place. However, despite the passage of time, the distance, and the chaos of the pandemic, the working group has continued to meet digitally, thus nurturing existing alliances and affection while still harboring the illusion of carrying out the actions they had planned but were unable to, a gesture that seems insignificant in the face of the great survival dramas we have collectively witnessed on a planetary scale over the past few months. To quote Sara Ahmed: “Survival can also be about keeping one’s hopes alive; holding on to the projects that are projects insofar as they have yet to be realized […] Survival can thus be what we do for others, with others. We need each other to survive; we need to be part of each other’s survival.”[5]

There is something in this incomplete performance that connects me to memories of political movements in which I myself have participated over the years. Movements in which the initial rage and drive are diminished by the wear and tear of trying to resist social injustices while the activists struggle to survive under voracious capitalism, which again and again pushes us towards demobilization and individualism.

The experience of Randy, Midori, Rojita and El grito allows me to understand the importance of care and cultivating the fragile flame of our bonds.

The forces opposing these communal exercises in protest and political organizing are abundant and very powerful, yet both artworks are beautiful metaphors for the many facets of transfeminist activism. They unite the voices of a diversity of subjects who have found in the patriarchy—racist, enabling, and capitalist—the root of their pain and oppression. By uniting their bodies in the same movement and their voices in a collective cry, these multitudes of dissidents care for and sustain one another. As Sara Ahmed puts it, “And that is why in queer, feminist, and antiracist work, self-care is about the creation of community, fragile communities […] assembled out of the experiences of being shattered.”[6]

In the words of Sayak Valencia: “[T]he transfeminism that we will address here is one that has emerged since 2008 through a network of transnational exchange. It can be located in the Spanish state, but is not of exclusively Spanish manufacture, since it is bisected by the practice and discourse of different migrant voices and corporealities embodied in different conferences, seminars, colloquiums, etc., held from 2008 until today and whose crystallization took place in the ‘Manifesto for Transfeminist Insurrection’ published on January 1, 2010, globally and virally on different websites.” Sayak Valencia, “Interferencias transfeministas y pospornográficas a la colonialidad del ver” [Transfeminist and post-pornographic interferences in the coloniality of seeing], e-misférica 11 (2014): 1-23.

AMETS stands for Alianza Mexicana de Trabajadoras Sexuales (Mexican Alliance of Sex Workers), an autonomous and self-managed organization of activism and collective care in favor of the human and labor rights of sex workers.

The Second Biennial of Arts and Design UNAM 2020 was titled Pedir lo imposible [Asking the Impossible], and was exhibited at the Museo Universitario de Ciencias y Arte (University Museum of Science and Art), orMUCA. The exhibition opened on February 8, 2020 and was scheduled to close on March 28, 2020.

“Se cumple tres años del feminicio de Lesvy en la UNAM” [It’s Been Three Years Since Lesvy’s murder at UNAM], La Jornada, May 3, 2020. Available here.

Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 235.

Ibid., 240.

Comments

There are no coments available.