For 50 years, in Mexico and then New York City where she moved in the eighties, Latin Americanist curator, former museum and non-profit director, editor and writer Carla Stellweg has advocated for a hemispheric artistic dialogue which, according to her, was never a given in the Americas. Terremoto’s director Dorothée Dupuis went to meet her at her loft in New York City’s Lower East Side.

Dorothée Dupuis: Last fall Pacific Standard Time, a contemporary arts initiative of the Getty Foundation, was held as every five years in collaboration with more than a hundred art institutions, galleries, and independent spaces in the broader Los Angeles area. This edition’s theme and focus was the connection between arts in Latin America and Los Angeles, as well as with the larger Latino arts communities. We decided to dedicate the fall issue of Terremoto to Chicanx/Latinx art practices, articulating the theme around the concept of smuggling. Since I learned about Artes Visuales, the bilingual quarterly magazine produced by the Museo de Arte Moderno (MAM) in Mexico City from 1973 to 1981—and which you were a co-founder and director of—I have been thinking about the striking similarities between our two publications. Could you first tell me about the concept of Artes Visuales? Especially about the issue dedicated to Chicano art in 1981? It seems you were the first magazine to really address that subject.

Carla Stellweg: Yes, we were the first magazine in Latin America to focus on Chicano art. In 1979, the Los Angeles Institute for Contemporary Art (LAICA, as it was known) invited me as an NEA (National Endowment for the Arts) Critic-in-Residency to edit a bilingual issue on Latin American art for their journal. I drew up a five-point questionnaire that I sent to a select group of Latin American curators, arts professionals, and artists living and working in Latin America, as well as some living and working in the US. Of the 5 questions, the last asked what they knew or had heard in regards to Chicano art. Only two people responded to this question, one was Hélio Oiticica and the other Luis Camnitzer. At any rate, the NEA required that I conduct two lectures around Los Angeles. At the first talk, there were two Latino guys who sat in the front row and posed some very articulate questions during the Q&A session at the end of the talk. Afterwards, they left before we could be introduced. Two weeks later, at another venue the same two guys were again seated in the front row. This time I approached them and commented, “You know, I am not going to do a different lecture than the one you already heard, so you might get bored!” I then suggested we had dinner together in Chinatown afterwards. It soon became clear that they had their fingers on the pulse of what was happening!

Before this I had started to look into dedicating a specific issue about the amazing new art coming out of Cuba—the first generation of graduates from the Instituto Superior del Arte (ISA)—this was a little before the Havana Biennial, which was begun by Yillian Yanes. Instead, I asked my new Latino friends, Roberto Gil de Montes, one of the founders of LACE (Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions), and Eduardo Dominguez or Eddy, if they would be interested in doing studio-visits all over town if I extended my stay, and suggested that perhaps, after assessing the material we looked at, we could think about doing an entire issue of Artes Visuales on Chicano art. My interest was more in the conceptual new art and popular Chicano visual culture—photography, comics, photo-novelas, video art—than the more traditional Mexican Muralist heritage.

This first issue on Chicano, or if you will, “Latinx” art—as it is called today, was not so much serendipitous, but the result of asking the right questions at the right time. If I hadn’t asked them to join forces with me, the Artes Visuales issue might have been a much more conventional representation of Chicano or “Latinx” art than the one we ended up editing together!

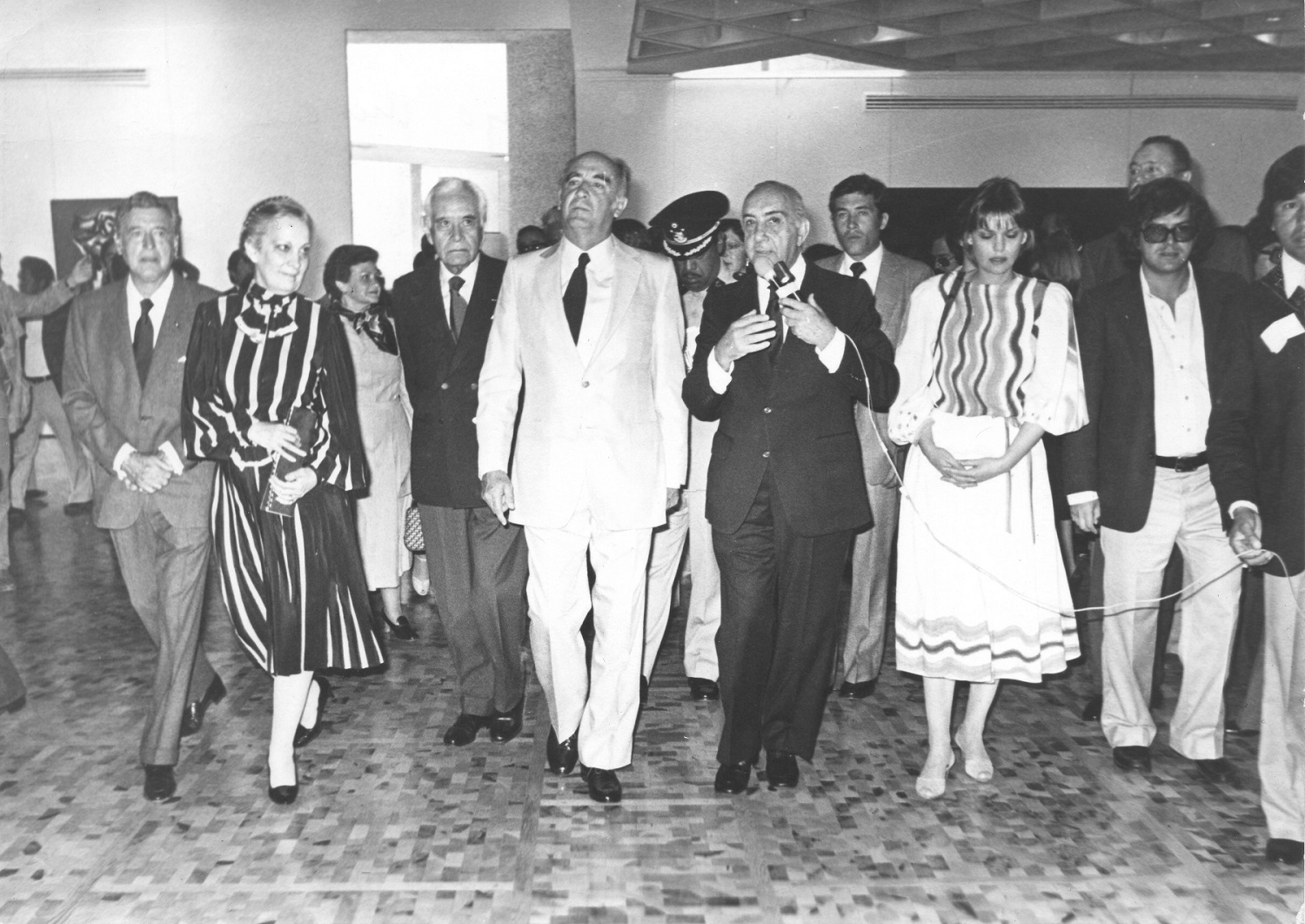

DD: You had this successful career in Mexico City starting in 1965 and through the eighties. You were editing the magazine Artes Visuales, as well as working with Fernando Gamboa, one of the most important institutional directors of his time. Then, in the eighties we find you back in New York. What happened?

CS: Well, the Mexican government closed the magazine, or rather they censored it! It had already survived two governments: that of President Echeverría, who brought all the intellectuals back (they had gone into exile after the Tlatelolco massacre in 1968) and that of José López Portillo. In 1982, President de la Madrid came into power. During the transitional time, just before the new president came into office, the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes (INBA) appointed a new chief of the Visual Arts Department, which the MAM was a dependent of. I remember him being very handsome. He stopped by my offices in the MAM and invited me to a fancy Polish restaurant in the Nápoles neighborhood, and with caviar and a bottle of frozen vodka on the table, he attempted to convince me to move Artes Visuales from the MAM to the INBA. I refused, and anyways they already had a magazine, La Revista de Bellas Artes. The day after, when my team and I returned from proofing the next issue at Imprenta Madera, very far away from Reforma and Gandhi, our offices had been sealed, and we stood on the sidewalk prohibited from going back in. Gamboa, with whom I was also working on the opening of the Museo Tamayo at the time, said, “Look, you have a loft in New York, go there a few years and when the next president comes in, you can return.” But I never went back, although Gamboa did call me five years later! As the artist Les Levine had once said, “Never go backwards or sideways, only go forward.”

DD: You often define yourself as a Latin Americanist—how does that include Latino Art?

CS: Prior to PST LA/LA last year, there were several panels at the Getty. I was invited to two of those, and Ruben Ortiz-Torres moderated one. In another panel regarding the LACMA Home show, the artist Daniel Joseph Martinez was one of the participants, with Mari Carmen Ramírez, Chon Noriega, Gerardo Mosquera, and several others. The subject of what Latino art is or was came up. Then, at some point, Martinez interjected. “There is no such thing as Latino Art!” It’s just like Latin American art, what is it? It can be many things!

Over the past 40 years the question keeps popping up. From my perspective, a Latin Americanist is someone who dedicates him/herself to the creating of platforms to further the visibility and knowledge around works made by artists from or in Latin America, whether they be political, conceptually engaged, or all the different forms of abstraction, including concrete, neo-concrete, kinetic, and optic art… In my case, it wasn’t a decision, it just happened. I am a Dutch citizen who moved to Mexico when I was 16. My intellectual formation was largely a product of my years in Mexico and Latin America. I adopted Mexico as much as Mexico adopted me. Being a Latin Americanist is not essentialist, it’s a practice, and in my case I made a point of including the Latino artists in that category. I didn’t grow up with Latinos, but today there are some 30 million US citizens of one or another Latino origin, a composite of immigrants from Cuba, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, plus all the other Caribbean nations, and Chicanos.

Returning to what Latin American art is: The need for a hemispheric dialogue has always existed.

Traditionally, in the US, the East Coast has always been considered to have the most economic and political power; New York City, Washington DC, Boston, all looking toward Europe and connected to it for multiple historical reasons. The military machine of WW2 forged our technological revolution, and the by-product of fast communication has changed everything, especially in the art world. During WWII and the Cold War, it was geopolitically important for the US to try to improve a hemispheric discussion because there was an increasing amount of Soviet-leaning governments in Latin America that were seen as a threat to US national interest, as well as its corporate business interests. I talked about that recently in a panel at the Museo Jumex, arguing that in order to talk about the concept of Latin American art, we must first talk about the 40s and the Cold War. The US Congress and Senate sanctioned those arts and cultural programs that became hemispheric in order to create alternative networks to those they had had previously with Europe—to learn what people were thinking, and the systems that those in Latin America were keen to support politically, economically, financially, etc. The US Cold War’s cultural thrust utilized abstract expressionism and the New York School, and promoted the work of Latin American artists such as José Luis Cuevas, Edgar Negret, or Botero for instance, in exhibitions curated by José Gómez Sicre at the OAS Museum of Latin American Art in DC, or in the seminal texts on Latin American art by Marta Traba.

Today, we seem to be at the tail end of abstraction, the various movements that were intelligently and solidly canonized by Mari Carmen Ramirez in her seminal exhibition and catalogue Inverted Utopias from 2004. To prefer protest-based and politically-charged art and what today is known as “relational aesthetics” seems to respond better to our troubled times and seemed for a while to be an antidote to the Frida Kahlo-ization (among other mythical figures) of Latin American art. Historically, figuration is more grounded in realism or anchored in social activism or, if you will, again “relational aesthetics.” Abstract art is more comfortable, neutral, and non-committed, easy on the eye and psyche.

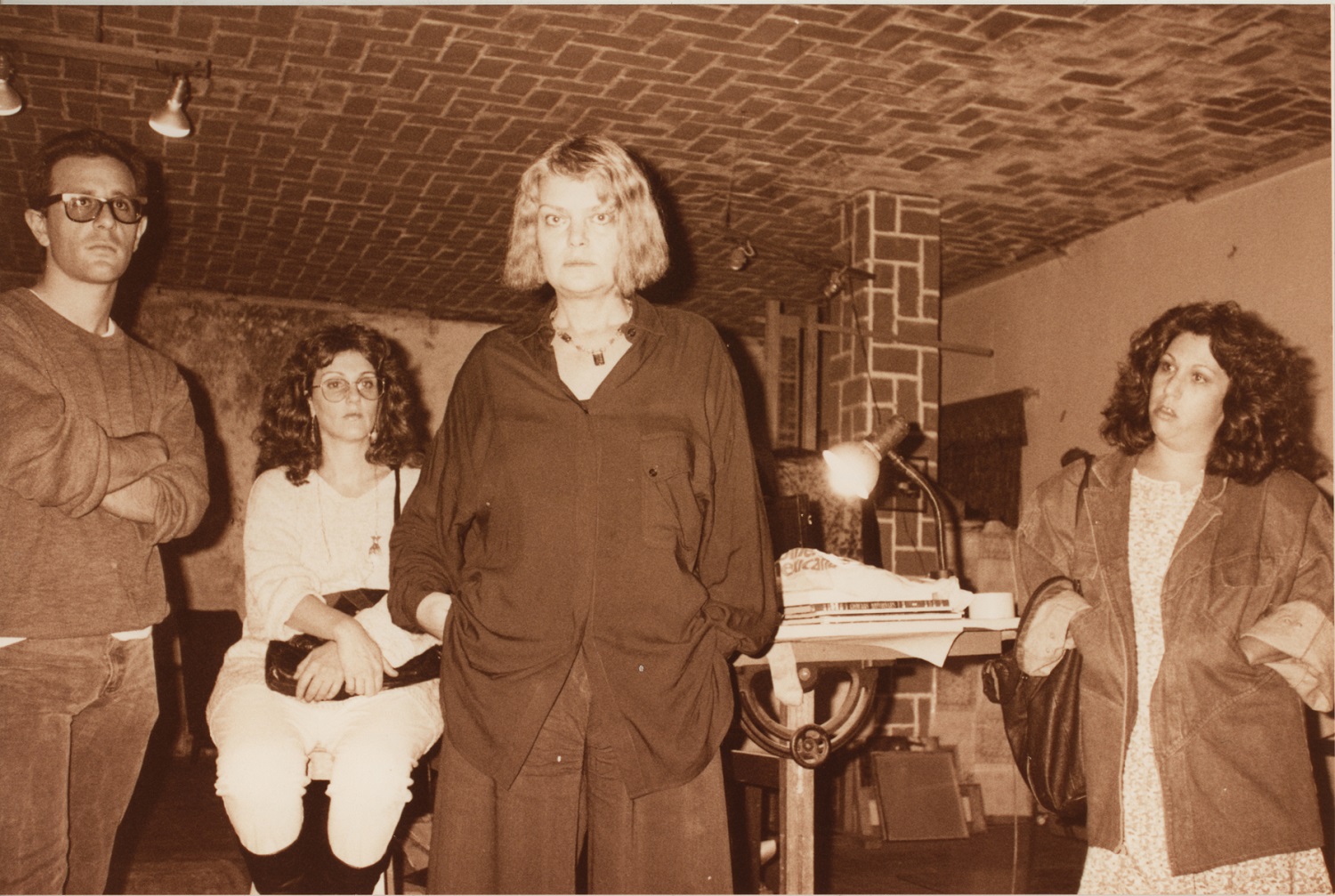

DD: In 1989, you opened a gallery in your loft in New York, leaving aside momentarily your institutional career. Why did you decide to do that?

CS: I had done all these other things and undergone many professional transformations, however it was always under the umbrella of institutions. It was time to be independent, do my own project, and not be tied to an institution and its policies—at least not for a while. I had lived and worked in New York many times, a few years, a few months. After Artes Visuales was censored and ceased to exist, I came to New York from Mexico in January of 1983. I had already leased this loft back in 1978 and used to come and go four times a year.

Artists would often come by to visit, and after the demise of Artes Visuales we were wondering where and how they could show and sell their work here in New York. It was clear there was an opportunity to introduce the public to something that I felt very strongly needed to be seen. Ana Mendieta used to come down to Mexico, which is how we became very close friends—at one point I even owned 12 of her works. She, as well as Regina Vater and Ana Maria Maiolino, who lived around the corner. There was Luis Frangella who died of AIDS—he lived on Forsythe Street, also around the corner. Catalina Parra from Chile was also here… I kept working freelance as a consultant until 1983, then opened a space—my first gallery—on Mercer Street in Soho, and then became the Chief Curator at the now defunct Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art (MoCHA). In 1989 there was a crash in the market. Many Soho galleries were closing, and I thought, “What goes down must go up, and what is up must come down,” and decided to open my second space, this time in the loft. Real estate was already quite expensive, and I was living in a 4000-sq. ft. apartment without walls—one huge space. Therefore, we began by building walls, isolating the kitchen area, etc., and that is how we started, inviting people from everybody’s network, people who mattered and who were influencers. I even did art fairs, and for a while in the nineties I was actually on the exhibition committee of the Miami Art Fair, way before Basel Miami, which was also held at the Convention Center.

DD: Did the artists produce works specifically for each exhibition or were they previously made works? How did you promote them?

CS: It was a combination. Some works were made prior. However, the program was always a dialogic process starting with an idea of the artists. One day I combined David Lamelas’s work with Luis Camnitzer’s work, who at that time were both part of an underrepresented generation of really significant conceptual artists. Nobody or very few people bought their work! I recall that in the late nineties León Ferrari came to New York to do a show at the Drawing Center. On that occasion, he brought 30 drawings, each at $300, which I could not place in one collection! The only museum person who visited the gallery regularly and motivated her board to do the same and to begin collecting was Marcia Tucker from the New Museum. My former institutional contacts basically just came to see what and who were there, to socialize saying things like, “You are doing such a great job, keep it up!” At that time, I raised the funds needed to keep the gallery going by speculating on the secondary market. I had a pretty good eye, especially for very contemporary works, and had built a clientele in Europe for that sort of work, some of whom then began also to collect Latin American art. Also, before I opened my gallery, I curated a show of Latin American artists working in New York at Samuel Dorsky’s gallery in New Paltz before it turned into a museum. After that, Mr. Dorsky and I remained close friends, and he was a strong supporter of the gallery until his death. In addition, the younger generations of Latin Americanists, who were then still studying, like Ana Sokoloff, Monika Amor, etc., would come and we’d talk and share my specialized library. In the process I became an ad hoc mentor—another role I continue to be interested in! In that sense, my space was a hybrid space, cultivating collectors to learn about and buy our art, while also acquiring knowledge that was not necessarily available in books. Then, in 1997, I was awarded a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship for the Humanities, and in addition I had already observed that the major New Y0rk galleries had started to incorporate Latino Artists in their program; my role had been to plant the seeds that were then beginning to bear fruit. That was the moment I decided to close the gallery.

DD: Do you feel that there has been a positive evolution of the interest in Latin American and Latino art in the US since you started working then?

CS: What has happened institutionally in the US and several European museums regarding Latin American art is the creation of Latin American Committees that finance acquisitions and fund curatorial positions and exhibitions, all in an effort to identify specific “Latin American” art with its own specificities and historical background.

During the Nixon years, the mandate was to seek “integration”: everyone living in the US should only speak English, ideas of the “American Dream” would be partially exploited visually to create stereotypes, etc. The question in my mind was: “How long does someone who is from the ghetto want to stay there?” And the answer was: “Everyone wants to get out the ghetto.”

It is true that we are looking at many positive results today, however, it seems to me to be taking a very long time for that “upward mobility” to happen. Raphael Montañez-Ortiz, founder of El Museo del Barrio and a Boricua born Neoyorican, shows with Pamela Echeverría at LABOR Gallery in Mexico City, which means she has a clientele for his work… Meanwhile, there are also many artists who are finally making it inside the institutional circuits and the marketplace, thanks to a few brilliant promoters and dealers and museum people, but many more are not.

DD: You are talking about Nixon and the way his presidency affected notions of how culture should function within society. Now there is Trump, a conservative of yet another breed. How do you predict his policies will affect the production of contemporary art in the Americas, both symbolically and on a production/market level in the next few years?

CS: My instinct tells me artists will be more and more inclined to feel that it is key and ethically responsible to do work that addresses Trump’s disastrous policies, which are pushing not only the US but all of the Americas further and further backwards. Just look at topics such as immigration, ecology, women’s rights, etc. How that art will be made, and in what shape or form will it come, I cannot predict.

As to the general field of arts and cultural: The Trump Era dictates anti-art. Dismantling the National Endowment of the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, just listen to his dismissal and highly volatile arts and culture tweets that are not just derogatory but despicable! Look at what he tweeted about the new US Embassy in London, whose opening he refused to attend. This embassy is filled with fantastic contemporary art—Mark Bradford, Rachel Whiteread, you name it. Anyway, Trump is a disgrace. We have a tough battle ahead but it has to be fought, resistance may not be enough.

DD: Can you tell us about a few of your upcoming projects?

CS: It would be great to finish a project I began with Gamboa back in the 1970s to show how art is transnational, with exhibitions of US artist who created a body of work in Mexico or Latin America. I had already done Milton Avery: In Mexico and After, and was planning on doing Robert Smithson, not just his Hotel Palenque, but all the works he did in the Yucatán, or Stuart Davis in Cuba… However, as we said earlier, we can only go forward.

With that in mind, I am working on putting together an anthology of several published and unpublished texts of mine, like the one I did with the Rockefeller Fellowship in the Humanities, If Money Talks Who Does the Exhibition Talking? that covered the so-called Latin American arts boom in the 1980s, exploring how funding effectively produced “art history” through case studies of five exhibitions that were curated in the US and traveled south, and five exhibitions that were curated in Latin America and came north. And then the best project is obviously to go to Mexico and write a memoir…

Comments

There are no coments available.