06.12.2021

The artists Elyla and Purificación exchange dreams and critical notions regarding mestizo identities subjected to the colonial apparatus in Nicaragua and Guatemala, which, in tension with their mariconería, outline artistic practices that make imagining other worlds possible.

Through what paradigms is an identity instilled in us? Knowing Elyla’s work, I suspect that the gender binary has had more implications for our identity assumptions than I could have imagined. In mid-August, with our memory wounded, as Elyla says, we began to meet in this sort of virtual non-space to talk about memory, political concerns, and the intuition that we are seemingly fucking doomed to remain screaming from these territories in the face of the quest for justice.

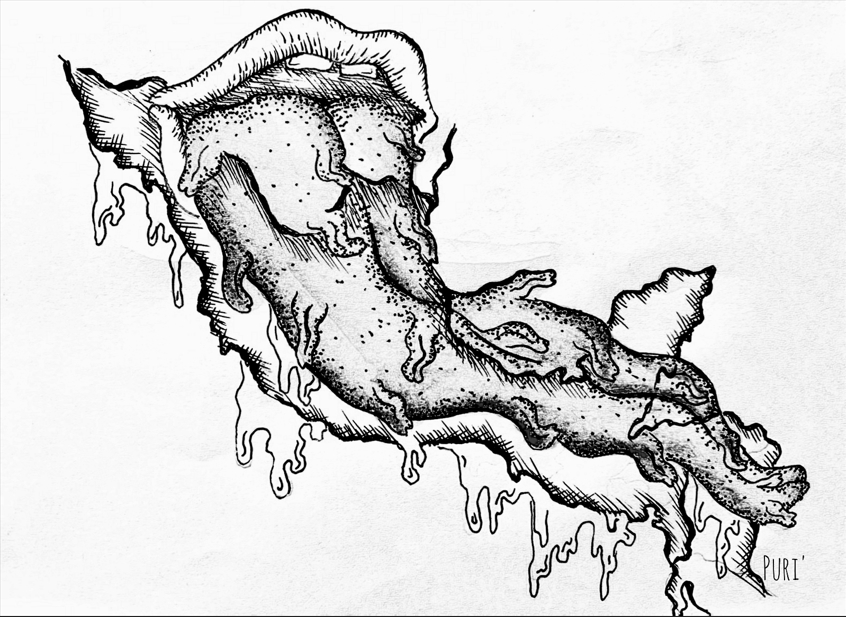

Elyla has embarked on a process of recognition of what they have called “routes for interrupting the hegemonic cultural narratives” of their territory (the Pacific region of Nicaragua). They question and reassemble the imaginary around their own mestizaje[1] to highlight how the colonial apparatus has eliminated any possibility of self-encounter with an ancestrality. Their artistic practice is a “fluidity stop” where the reinterpretation of symbols and languages seeks a new space of existence; a place which nestles them together better. Barro Mestiza, their first solo exhibition (Carazo, Nicaragua 2021) is the result of an exploration that, according to their terms, dismantles the colonial apparatus characterized by the gender binary.

We began to imagine an allegorical route: licking each other, body to body; examining our forms and possibilities, dancing with them and reviewing the common memories running through us like the perceptions and flavors that the tongue recognizes.

Here in Guatemala, on this side of the wound, the collective Organización de Locas[2] Centroamericanas y del Caribe (ODELCA) [Organization of Central American and Caribbean Queens] shares the urgency for a confrontational semiotics where jokes, fiction, and parody become a formula for corroding the propaganda and hegemonic narratives of the postwar period. Naming ourselves in dissidence far from martyrology, we are loosening our tongues!

Elyla (E): I would like to begin by asking questions, because that is how I started this journey: How to translate mestizaje? What does it mean to be mestizx? I ask myself first and then everyone else: In what ways is mestizaje lived in Mesoamerica? This simple exercise of translating the term mestizaje aims to reflect on the bodily-political affectations implied in assuming a mechanism of colonial and racial identity in our territories. Let’s really make this a bodily exercise, a stopping and asking ourselves:

Can I feel mestizaje in my body? Is there even a sensation?

Have I given myself the time and space to identify it? Does my tongue move when I pronounce mestizaje? How do I pronounce it with a loose tongue? What is its color? Are he, she, them, they mestizajes? What memories does my mestizaje carry? What stories exist in our respective family lineages when we begin to name ourselves mestizxs? Is naming oneself mestizx the same as naming oneself white-mestizx? What privileges or access do I have as a mestizx? What political implications for the land itself and the Indigenous people of Mesoamerica do these names have? Can I recognize mestizaje as a colonialist apparatus erasing Indigenous history, knowledge, and ancestry from our bodies? And if so, what new identity can I give birth to and what are the access points to my ancestry? And finally, could this dissident sexuality be my greatest anti-colonial tool in relation to mestizaje?

Purificación (P): With Barro Mestiza I went over and over the routes you devised to challenge the assumptions from which we have been taught to name ourselves: the patriarchal, the “pacificocentric”[4] back in Nicaragua and the supposed “Ladinidad”[5] here in Guatemala. Barro Mestiza is a questioning of the marked binary logic; it appeals to the possibility of searching in order to imagine a cochón utopia, taking huequitud[6] as a banner to find more situated possibilities, a search beginning with questions, and blindly giving tools, routes, and ways to rewrite your own body. Your artistic practice proposes some answers to the problems posed by the identity arbitrarily assigned to me, a consequence of a colonial splinter, that incarnated fiction: the supposed “Ladino.” I come from a region where for 150 years the Ladinization of the territory and the people has been pursued. As a hueca, how am I to consider my ancestry when I have been amputated? The search for my ancestry has been solitary; a meeting and misunderstanding of potential corporalities wading between the forbidden, the assumed, and the secret in resistance. In Barro Mestiza there are kinder possibilities for knowing ourselves to be less boxed in, more stripped of the colonial sign.

(E): That solitary search resonates with me. At some point I also felt a profound loneliness in this process; I think it is important to know what that loneliness speaks to us about. In Mesoamerica, intersectional conversations between raciality, decoloniality, and sexual dissidence in collectivity are urgently needed. However, I recognize that the first conversation and work to be done in terms of depatriarchalization and decolonization processes is with yourself, with your own body/memory/territory. I believe that if you have been constructed from the paradigm of mestizaje or mestizajes, the worst thing you can do is to paralyze yourself in a certain mestizo commiseration or colonial/Christian guilt, there is no time for that. Being cochona or hueca, fluid or dissident, does not take away the racist, sexist and patriarchal—our colonial construction. Therefore, there is a lot of work to do with yourself.

(P): When I saw your Torita encuetada (2021) I felt with certainty the ritual in the hollow being. Listening to the beginning of your performance, when we hear the chant “we are alive behind your shadow,” we begin to perceive an existing anti-colonial voice, the product of a given heritage, of struggles and battles which were claimed the past. The noise of many voices, in Barro Mestiza we are existences repeated in the lived cochón experience of each comrad. There is a being looking for memory, which is known and recovered in the huequitudes, in the cochonadas of other compas; that mariconería, the jotona[8] spark that has to serve us to make a path together in which to nestle a being, a feeling of more togetherness. Starting from there, maybe we can infect the dissident cochones of an imposed order that makes us uncomfortable. This search offers a wide path to begin to recognize ourselves without fear, with the wounds that history has engraved on our chests, with the courage to know we are scratched but standing up to claim a less crude and invisibilized way of living.

(E): That song you are talking about belongs to Susy Shock and her tribe. With her authorization, in that performance I integrated two of her songs, “Mariquita Linda” and “Torita Suelta.” Torita encuetada is a ritual based on a Nicaraguan cultural practice called toroencuetado, which I redefine through my exploration in order to propose an encounter between a corporality built from mestizaje (myself) and another from the Indigeneity (my friend and teacher from the Monimboseño people, Gustavo Herrera). During the ritual I ask him to set me on fire in order to be born from the ashes; memories of fire held by our grandparents, whom I ask to give me the opportunity to continue with this transformation. And what about you, how has your journey of digging up memory been?

(P): My path is bordered by family militancy punished with forced disappearance and exile by the Guatemalan state during the so-called “internal armed conflict”. Now my family keeps, perhaps with less enthusiasm, the thirst for different worlds. Even with the heaviness of this family memory, I like to think of myself as heir to their processes of struggle, their rage and dreams. It is clear to me that they are also on this journey, they lead us to a place of truth in the word, their voices and concerns color our butterfly wings red. The ancestral women who gather around this butterfly body, in other words, marika with marika, are the sought-after lineage, the best-kept secret in history. I think of the many denied weirdos, named out of insult and contempt. Chosen sisterhoods, they too are a living heritage. I think of María Conchita, whose assassination led to the first public demonstration for sexual and gender dissidence in Guatemala.[9] María Conchita’s struggles live on in me. In this region of hybrid regimes, memory is our light against detachment from the truth; memory motivates us not to abandon the dream of a warm existence where history screams as much as we did in life.

(E): I name myself cochón/a/e/e/x slash mestiza from the greatest authenticity I have found in my process so far. I also name myself “activist” or “non-binary” as a strategy to occupy a seat at the table of politically correct LGBTTTIQ+ representativities and raise other reflections belonging to my body in order to generate cracks. There is a northern loca, William S. Borroughs, who I believe was deterritorialized from identities. In their writing proposal they said: “Language is a virus from outer space.” I believe that if William was alive, the cochonas and huecas would answer this loca that yes, language is a virus, but not from any outer space, rather from a space called colonial violence with a piercing history.

(P): I imagine and laugh at the thought that if one day we were all gathered together in a square, we would be condemned to the joy of demanding a dignified existence that includes longer tongues. Of course, first we have to recognize that our “identities” have been co-opted by the north.

(E): There is much to question about the northern influence of non-binary and fluid identities in these territories. Let’s ask, isn’t the non-binary and/or fluid identity a perfect mechanism for inclusion in the modern colonial and mestizo model of the territory?

How do we situate the non-binary as a sensitive trans experience born from an honest corporeality which rests in our intimate/personal/historical memory? Is it even possible?

What does it imply to mutate the non-binary/fluid/queer into an anti-colonial space of political agency for our ancestralities? How can the non-binary be articulated with the trans-binary and feminized transvestites struggle through a relationship that isn’t flattening or opportunistic towards the spaces already conquered by them?

(P): To get closer to possible answers, we should be well-licked to arm ourselves against the common enemy: licking amongst ourselves so as not to lick ideas responding to other regions, especially the north. Out there, the system continues to tie us up in bundles as if they were not afraid of us. We are huecas, our fear has been transformed into enjoyment and pleasure.

(E): In Mesoamerica the invitation is to lick ourselves in order to begin to learn about our own cochona, hueca stories, and those of all dissident corporealities.

We must begin to savor ourselves, to turn into cannibalistic tongues, to escape from language and melt into pleasure.

(P): The road is already made; it has begun to open for the huequitudes for a long time. All that’s left is for us to arm ourselves with tinsel and put on our highest heels to imagine futures in which the chest facing the sky is a greeting more queer than combative. Futures where we honor the lineages preceding us that whisper their existence to us. From our chests, those ancestralities will sing and invoke other dissidents in the uproar. Our tongues will be with them and with those who come to lick us. The tongue will also be the best instrument, the best practice of recognition in the face of a world that sees the butterfly house as a mass without nuance: licking to know that we are gathered together, where the flavors are recognition of different forms and terms, from which other locas are gathered in this drift called “history.” Prepare your feelings, once we have learned to swim through the slime of so many strident locas, in this sea we will weave ourselves like a mesh embroidered in cross-stitch to keep us all afloat.

Translator’s note: In Latin America, mestizaje/mestizx is a political identity that can be understood as an ethno cultural syncretism that emerges from the colonial wound.

Translator’s note: A pejorative word used to mock non-heterosexual behavior, which literally means “crazy.”

Cochón is a word used to refer to dissident sexualities and genders in the territory called “Nicaragua”.

Pacificocentric is a political, cultural and economic paradigm established in the sociogenesis of the Nicaraguan. It naturalizes and assumes, under a colonial logic, criollo-pacificocentric cultural imaginaries based on whiteness which envisions a Nicaragua by and for the Pacific region, excluding from the project of nationhood the territorial processes of the Caribbean region. See more: Larry Montenegro Baena, “La estructural espera de los pueblos de la Moskitia. El racismo de la espera,” May 19, 2018, http://montenegrobaena.blogspot.com/2018/05/la-estructural-espera-de-los-pueblos-de.html.

Ladinidad is the colonial term used to refer to the “hispanicized” population in regions of Central America and Chiapas that were not part of the peninsular, criollo or Indigenous economic and political elites. See more: Ronald Soto-Quiros, “Reflexiones sobre el mestizaje y la identidad nacional en Centroamérica: de la colonia a las Repúblicas liberales,” AFEHC, no. 25 (October 2006).

Huequitud is a word used to designate dissident sexualities and genders in the territoriality called “Guatemala”, which literally means “hollow.”

Chontal, according to Nicaraguan and Central American historians, as well as some colonial chroniclers, is a word of Nahuatl origin which can be translated as “foreigner”. The Nicaraos used it to refer to the oldest inhabitants of Nicaragua who possibly came from the Maya Chontal Tabasco or Oaxacan ethnic group. The Chontales were later expelled by the Chorotegas.

Translator’s note: Jotona is another pejorative word used to mock non-heterosexual behavior that is appropriated with a flamboyant connotation.

In October 1997, a group of people marched through the historic center of Guatemala City demanding justice for the murder of María Conchita, a transgender woman killed by two Guatemalan military soldiers. That day was the first time the sexual and gender dissident community took to the streets.

Luis Morales Rodríguez, Niebla Púrpura (Ciudad de Quetzaltenango: Editorial Sión, 2018).

Comments

There are no coments available.