22.06.2020

Through a journey, the writer Rafael Toriz articulates a prose that takes us to the deep jungle to evoke, from the opioid, the ancestralities that sustain the tropics while exploring the malleability of their languages.

I

I stand on all fours above the stone’s jaw, beneath the sky where a flock of grackles is perched, the pervasive panic of the dense forest dominates. On the tomb of Ukit Kan Lek Tox, whom I watch over every night and day, it is possible to hear, among the whispers of the ivy, how the vertigo climbs higher and higher up into the celestial vault, how it draws the horizon and dissolves into the remote distance

Like the tide, the forest lights up little by little as the wind blows across it in the iridescent ebb—which men stubbornly still insist on calling green—that breathes like an animal overcome with fatigue.

It is from the Acropolis that one is able to measure the magnitude of this creature. As old as the stars, the nahual[1] of the nahuales insists on perishing unknown; its last vestige will be the outline of a pawprint in ash.

According to the tales recorded in the Relaciones histórico geográficas de la Gobernación de Yucatán [Geographic Histories of the Government of Yucatan], it was the encomendero Juan Gutiérrez Picón who first describeed the Yucatan in a foreign language, in around 1579:

The central seat of Tiquibalon [Ekbalam] was given this name by a great man who was called Ek Balam, which means “black tiger,” and who was also known as the “Lord of All” […] He built one of the five buildings, the greatest and the most sumptuous, and the four others were built by other lords and captains, who recognized Coch Cal Balam as their supreme lord… It is held to be true among the natives that [these lords] came from the East in large numbers, and that they were a brave and eager people, and that they were chaste.

*

With the conviction of a convert, Daniel had been insisting that I do this for a long time, and his naturally generous spirit made me a little unwilling.

—Ok, enough putting it off already, let’s go to Montaña Fay. You need this, we all do. If I could, I would bring my boss, too. It’s a carnal journey. I don’t know what all you’re thinking about so much.

I have never needed to be asked twice to try something new, especially when an invitation to the country involves exploring a sliver of those sensible paradises that lie in reach of the mouth. However, my encounter with the lizard was no sure thing; here, I mean to suggest that the intelligence of plants likes to lie in wait for the festal object until it is just right.

The situation was resolved not so much because of Daniel’s insistence (although everything derived from his eagerness), but because Juan Patricio had scheduled a Kambo session in the direction of Las Lomas, which would serve as a full-on prologue to my encounter with the Lady of the Southeast. Or at least that’s what they said.

That Saturday, we arrived at the yoga center, where they also offered health consultations in the back, with the shaman and the toxin secreted by the Phyllomedusa bicolor—that is to say, the mythic Kambo frog, that intensely green creature which populates the Northeast of Brazil, as well as Peru, Bolivia, Colombia, and Venezuela.

According to those familiar with it, the frog’s venom works on the physical, psychological, and spiritual axes of whoever ingests it. I have no doubt that this is true, although I am in no position to judge, since, from the moment the knife touched my freshly cut skin—four kisses on my shoulder, like a little death—a single word took over the entirety of my vision and consciousness before I collapsed on the palm mat: Xkanleox.[2]

II

The ceremony would take place along the detour to Naolinco, in the shell of a hotel under renovation. Even though it wasn’t the cold season, the fog was thick. The night was icy, especially for those of us who had the tropics in our blood.

The road to Naolinco has always been shitty, not only because of the winding curves peppered with potholes but also because of the steely fog in which even the surest of people can become lost, not to mention those unfamiliar with the route.

It wasn’t hard to get there. Once we took the detour, we followed the old road towards Los Cedros. We entered through a backroad that forked off the left side of the road and that continued straight ahead for some thirty yards before ending in a plaza lined with orange and mamey trees.

I’m not sure when the delirium began. After drinking the brew that the shaman had prepared and concentrating on the ícaros,[3] I started to feel like a blind knot of scum was dwelling in my entrails, stewing in my stomach and rising up through my esophagus to my throat.

The night was cold—some ten degrees colder than Xalapa, just barely tolerable. I was shocked by how many people had agreed to attend the ceremony in this weather. We were a little more than 50 souls of all different stripes, but with a shared popular bent. They put us in a hut with brick walls and a tin roof. We looked like people staying in shelters like the ones the government erects when there are sudden spikes in population or hurricanes. This confused me since I had developed a very different idea of the kind of person who was interested in alternative medicine from what I had seen in Mexico City, where it always involved people with a very characteristic profile of urban and middle-class extraction. So, when I discovered how widespread the use of ayahuasca was among the general population, everything seemed to make sense: reality in Mexico has been so painful for so long that whoever is able, chooses to face these horrors (horrors that have for a long time now constituted brokenness) with whatever tools they can.

*

I hunted jaguars, many of them. I am a hunter of jaguars. I came here to hunt jaguars, and for no other reason but to hunt jaguars. Nhô Nhuão Guede brought me here. He paid me. I got the leather, I earned money from the jaguars I killed… Nhem. Black jaguar? Here there are many pixuna, many. I killed them too. Hum.. hum.. Black jaguar crosses with the spotted jaguar. They came swimming, one behind the other, heads above the water, the line of their spines above the water. I jumped onto a branch on the bank of the river, I shot them dead. First the male, jaguar-pinima, who came first. Can the jaguar swim? Uh, he is a swimming bug! He crosses the great river in the right direction, and gets out where he wants…”

*

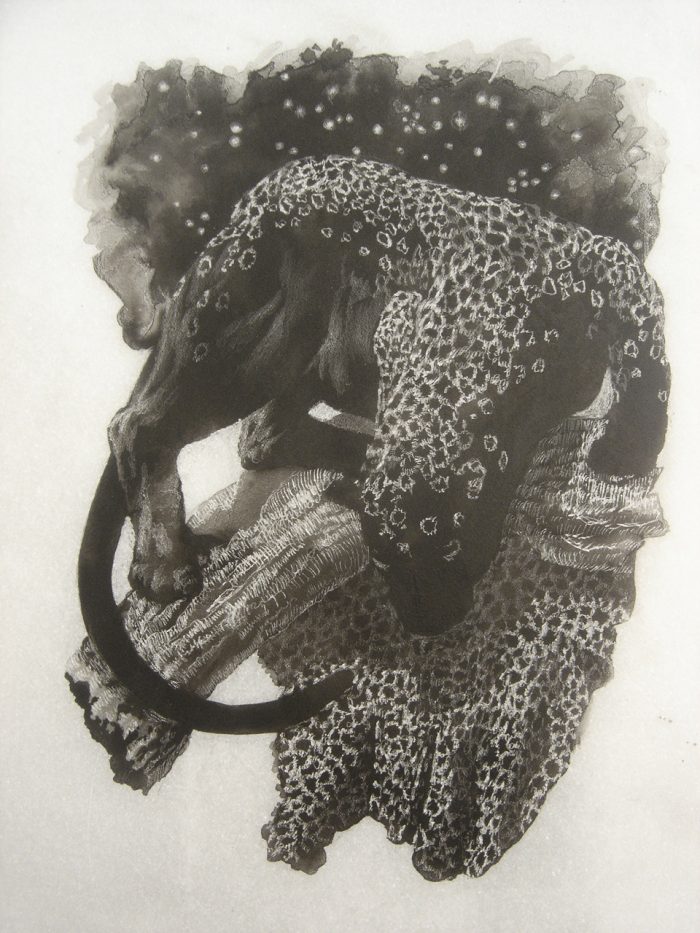

Of all the felids, the only one whose coat approaches greatness is the jaguar. My skin is infinite but my skeleton is a mix of the ocelot, the cheetah, the tiger, and the leopard. Hence the robust look. The jaguar, possessing all the powers of his agnates and a vestige of writing, is the god of the universe (the jaguar, in his perfection, gives light to the stars in the jungle of the night).

Very ancient peoples—like the people of the land of rubber (Olmec)—traveled upon my back in order to cross over into the land of the dead at dawn. The jaguar was also the destroyer of the cosmos, the brightness of the morning, and the darkest of the suns. It is written that one day he will return to drink of our blood and forge a new man out of our corrupt bodies. But the jaguar is also multiple and precious. If you catch sight of him just before he attacks, it is possible to discern the outline of his silence, his immaculate darkness: in this moment, the panther appears.

*

I’m not sure when the delirium began. After drinking the brew that the shaman had prepared and concentrating on the ícaros,[3] I started to feel like a blind knot of scum was dwelling in my entrails, stewing in my stomach and rising up through my esophagus to my throat. A sense of fleshly disgust, and not only because of the medicine: what was festering inside me was my own poison. Only when this filth left my body, wringing me out like a mop, did I see the eyes of the demon on the floor and remember that in the scope of the earth there are ancient, incorruptible, and eternal entities; any one of them could have been being the sought-after symbol. A mountain, or a river, or an empire, or the configuration of the planets could be the word of god. But over the course of centuries, mountains flatten and the course of a river often changes, and empires meet calamity, and planets reorganize. There is movement in the heavens. The mountain and the star are individuals and individuals expire.[4]

In this memory, the figure of Tzinacán also appeared along the dividing wall, obsessed with looking at me in the spotlight. Little by little, the memory of my panther body regained strength, revealing to me that my false life as a man had only been a pretext to provide me with perspective and to celebrate the name and place of my nahual. Ancestry overflows into the human.

I wrote these words in the notebook I brought with me—something told me that I had to conserve them, even though they have no meaning for me when I look at them now, since things rebel at their destiny of being signified by words, they reject that passive role that the system of signs would like to impose on them, and they recover the place that has been usurped; so they submerge the temples and the bas-reliefs; once more they swallow up language, which had tried to assert its own autonomy and establish its own foundations as though it were second nature.[5]

I saw the mountains that rose out of the water, I saw the first stick men, I saw the jars that turned against the men, I saw the dogs that wrecked their faces. I saw the faceless god behind the goddesses. I saw the infinite processes that shaped a single happiness and, understanding it all, I was also able to understand the word of the tiger, who really never wanted to say anything at all.

Do you know what the jaguar thinks about? You don’t know? Ah, well then learn: the jaguar only thinks one thing—that everything is beautiful, good, beautiful, good, without running into anything. This is the only thing it thinks, all the time, long, always the same, it thinks like this while it walks, sleeps, does whatever it does… When something bad happens, then it will suddenly squeak, roar, become full of rage, but it doesn’t think about anything: in that moment it stops thinking. It is only when things calm down again that it starts thinking again, exactly like before…

In the midst of tense calm, like a muscle torn open, I contemplate the dawn breaking over the tomb of Ukit Kan Lek tok, thinking, among the scattered ashes, that no mere man would be so sure of himself if he had to face, body to body, the only lord of this region.

—

Rafael Toriz Writer and cultural critic, he has published the books Metaficciones, Animalia, Serenata, Del furor y la deconsuelo, La ciudad alucinada, and the autobiographical montage La distortión. Graduated from Hispanic language and Literature from the Universidad Veracruzana and from the Art and Curatorship program of the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella. He currently lives in Buenos Aires, where he dedicates to radio broadcasting, cultural journalism, and curatorship. He recently selected, prefaced, and translated the book Galaxia de un hombre solo; verse, prose, and miscellany by Fernando Pessoa.

—

This text was translated from Spanish to English by Chloé Wilcox.

Among the Maya and other Mesoamerican indigenous religions, a nahual is a human being who can take the shape of a jaguar.

A proper noun in Maya which means “mother of the gods” (although sources are not accurate).

Italo Calvino, “The Forest and the Gods” in Collection of Sand, trans. Martin McLaughlin (Boston, Mariner Books: 2014), 193.

Comments

There are no coments available.