10.05.2021

The curator Francisco Lemus reviews the artistic practices that arose during the nineties with the arrival of HIV/AIDS in Argentina, which posed questions about life and death that are worth remembering given the vulnerability of the present.

Today, those of us who can find ourselves working from home in the face of a pandemic that, due to its particular nature, seems to have suspended what we knew as the “social”—that is, the ways we used to connect with one another emotionally and materially. The plague underscores the vulnerability of bodies and hastens poverty. Ideals about personal growth (confronting the economic crisis) and denialism (avoiding implementing health policies) circle the globe as we negotiate with death.

The “pink plague,” so-called for the pink color of the Kaposi’s sarcomas that appeared on the skin of the predominantly gay patients, was one of the many vitriolic terms thrown around in the press. The discursive construction of the virus straddled scientific knowledge, moralizing language, and old homophobic myths. Its integration into culture generated new symbols and updated others, which we can see in the accounts of plagues and illnesses discussed in euphemisms in the obituaries. The locus of fear shifted to saliva, touch, and sharing things with others. Some priests attributed it to a divine punishment like that of Sodom, doctors recommended monogamous relationships, sexologists advised masturbation and phone sex. Little was known about it, but plenty was written.

HIV arrived in Argentina amid a landscape of political fragility and economic deterioration that was exacerbated years later by hyperinflation, looting, military insurgency, and the preemptive surrender of presidential power. To this panorama, we should add the arbitrary arrests of gay and transgender people in the streets and in nightclubs as well as a lack of official resources for AIDS prevention campaigns or for accessing reagents for testing and hospitalization. This brought with it the formation of networks at the national level. At the beginning of the nineties, the agenda of these groups was totally committed to saving lives and to making death more dignified. Some activists wore masks to the first pride parades, hiding their faces out of fear of being recognized and fired from their jobs or thrown out of their houses.

The fantasies surrounding the first convertible currency, fitness culture, and corporate identity contrasted with the critical development of the disease. The virus transformed the governance of bodies at the same time as the onset of neoliberalism. Gabriel Giorgi maintains that HIV accentuated the stripped status of some groups with respect to institutions. There were no assurances granted for those who lived lives that didn’t conform to the norms of the heteropatriarchy.[2] Of the differences between HIV and the current pandemic, I’d like to highlight two: HIV was and continues to be a stigma machine and COVID-19 was cured in less than a year. The first high-profile carriers of the former were homosexuals, drug addicts—the “underworld”; the latter managed to slow down the economy and thus became a global problem. But like all plagues, both immediately posed a question about life.

In a context of precarity, art was experienced as a practice of freedom. Subjectivity ran through everything: themes, processes, discourse. The personal acquired an unprecedented place in representation.

This didn’t mean a withdrawal from politics with a capital P, nor a total evasion of the public, but an influx of micropolitics as a legitimate form of ordering the symbols of the era. While these transformations took hold, HIV advanced through bodies. People were creating at a dizzying rate, but also bidding farewell to friends and lovers.

The artists of the Galería del Centro Cultural Rojas—an emblematic nineties art space directed by Jorge Gumier Maier—recall Omar Schiliro’s wake in 1994. They brought some of his pieces to the funeral parlor, the body was made up, and the coffin was decorated with pearls, vials of perfume, and a plastic magic wand. That same year, the artist Liliana Maresca was sent off with magnolias in the cemetery. Years before, in 1991, Batato Barea’s farewell was full of balloons. Sergio Avello, his friend, made a cross out of small yellow balloons and arranged it like a flower crown. Feliciano Centurión passed away in 1996. He had hidden his diagnosis with macrobiotic soups and alternative therapies. By then, he had already buried half of his friends.[3]

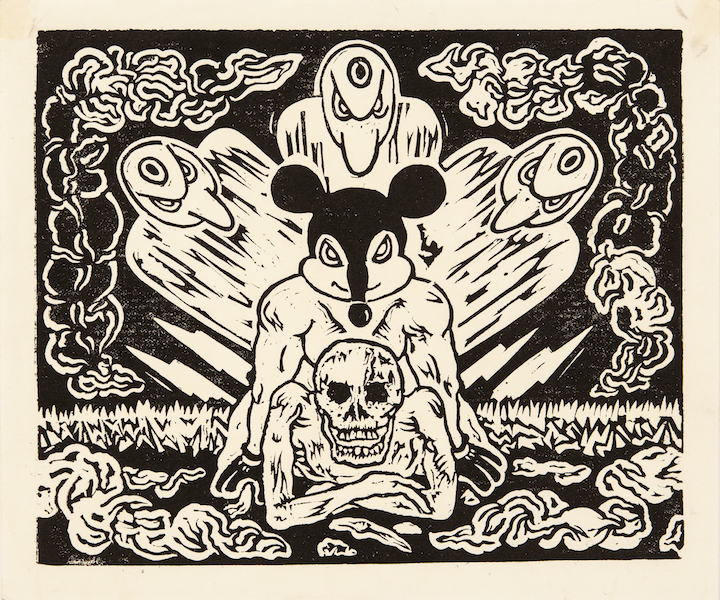

Art in Buenos Aires was cut through by the appearance of HIV and its lethal development over the course of two decades. Artistic practice intensified, and ties of solidarity and care were drawn throughout a community of artists battered by the military dictatorship and a crisis that obscured the future. The aesthetic matrix that enabled the production of contemporary art can be considered through a prism of seropositivity in which images interact with one another, infect one another; they respond directly to the appearance of the virus, as well as obliquely illuminate the weathering of bodies. As we became accustomed to HIV, the images transformed. The end of the eighties was marked by melancholy and the rhetoric of blood. The conditions for making art were suddenly swept away amidst the perplexity that the arrival of an unknown disease when it was least expected produced. The nineties presented an arc of tension between adaptation to the virus and death; by then, bodies were exhausted.

In the history of feminist art in Argentina, the Mitominas exhibitions represent a moment of intense visibility. It is thanks to the research of María Laura Rosa that we know about this project that went unnoticed in the first studies of the art of the post-dictatorship era. The 1986 and 1988 exhibitions brought together artists, writers, poets, musicians, feminists, and various activists from the first years following the dictatorship.[4] The first edition grew out of an initiative organized by feminist activist Monique Altschul and writer Angélica Gorodischer and built off the myths surrounding the idea of woman. The second edition, Los mitos de la sangre [Myths of Blood], opened in November 1988. This exhibition aimed to raise awareness about gender-based violence and the HIV crisis. Blood was a fluid capable of uniting the agendas of women and gay people, artists, and the general public, in a single exhibition. This edition of Mitominas pushed beyond the limits of what we think of as an exhibition. At the same time that it gave rise to feminist art, it expanded depictions of HIV and considered the issue in an intersectional way.

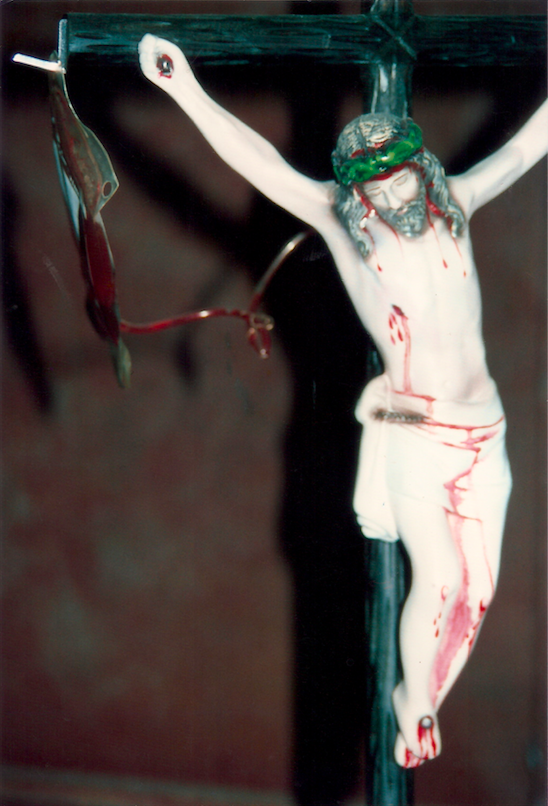

Liliana Maresca exhibited her work Cristo [Christ], a Santerían statue of a crucified Christ from which hung a hose and small transparent bag with red ink simulating a self-transfusion bag. A few months before, Maresca had been diagnosed as HIV positive. This small work, now lost, foreshadows a process that she developed over the last years of her life: projecting an image, a metaphor, onto the body—a vehicle of desire, a vehicle of sacrifice—and, at the same time, desecrating history. Maresca’s piece was censored. The cultural center where the exhibition was staged stands next to the Basilica of Our Lady of the Pillar in the Recoleta district. The faithful screamed bloody murder at the sight of this corrupted Christ. In Buenos Aires, the relationship between contemporary art and Catholicism has always been controversial.[5]

Pombo’s painting suffered the same fate as Maresca’s piece; there’s no record of it, it was thrown in the trash. We know that it was painted on a green background and featured orange flowers with the inscription “virus.” In the center, a large graphic flower rose up from the cover of an album from the seventies, bearing the words adorando la vitalidad [worshiping vitality]—one of the verses from the song Una luna de miel en la mano [A Honeymoon in a Hand]. Pombo wanted to pay tribute to Federico Moura, the leader of the group Virus who passed away from AIDS a month after the exhibition opened. Moura’s death marked the end of an era in which the effervescence of the return of democracy had allowed for hedonistic forms of entertainment and cultural production that contrasted with the repressive behaviors that the dictatorship had implemented. AIDS brought a momentary end to this new openness.

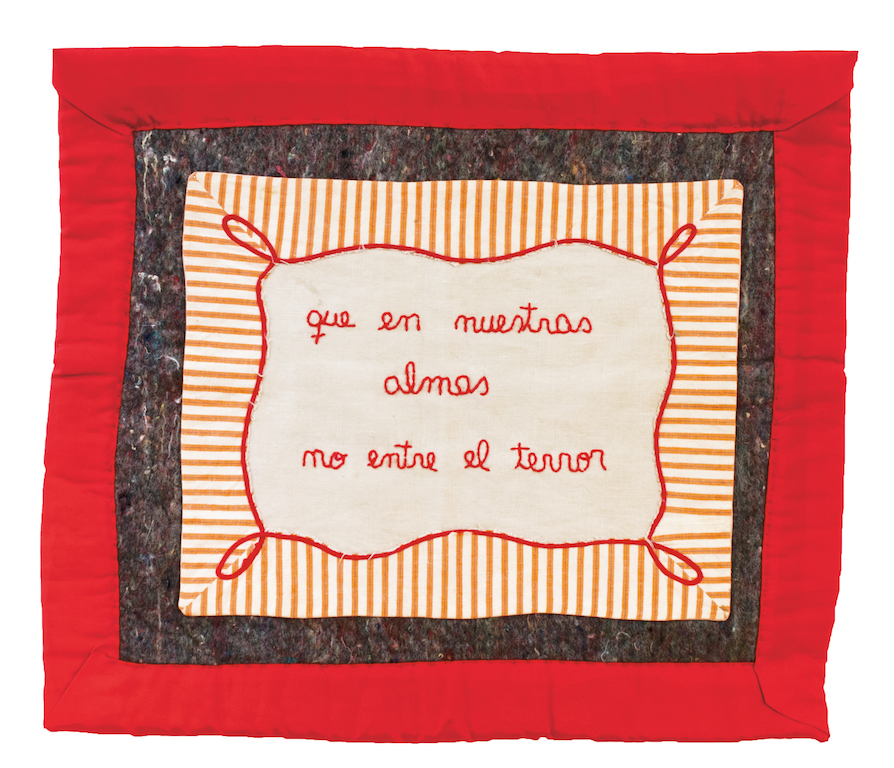

At the time of his death, Feliciano’s workshop was full of pieces with phrases that he would rapidly embroider on any cloth surface—works that slipped out of his hands to reveal a private world traced within the four walls of a house and a group of friends. He had found a way to cling to life and, at the same time, craft a legacy, a constant preoccupation for artists under forty who, in the face of this environment, were desperate to leave behind a trace of their existence.

In the nineties, the artistic practice began to become disconnected from activism. There were few projects that went beyond the limits of the art world. This disconnection had to do with the professionalization of the visual arts. What had worked within the realm of underground and minority politics splintered with the passage of time and found its own channels of circulation. In the art scene, transformative forces—the imminent consequences of life in a democracy—and the conservative forces typical of the elites and the culture of dictatorship were constantly colliding. Within that conflict, the scope of action had its limits. HIV was understood as an ominous experience. Paradoxically, it was the television of the nineties—hypersexualized and sensationalist—that enabled the activists’ most forceful declarations. To say that you were gay and lived with HIV went beyond just coming out of the closet, it was to take a radical position in the public sphere, an expression of resistance against the pristine image that neoliberalism was establishing through consumerism. The disconnect made it so that works of art didn’t intersect with the performance of activism, but remained anchored to a genealogy of contemporary art in which the autonomy of the field prevailed. The price paid was the objections to and the im- possibility of tying together art with micropolitics, the virus with an aesthetic, until years later.

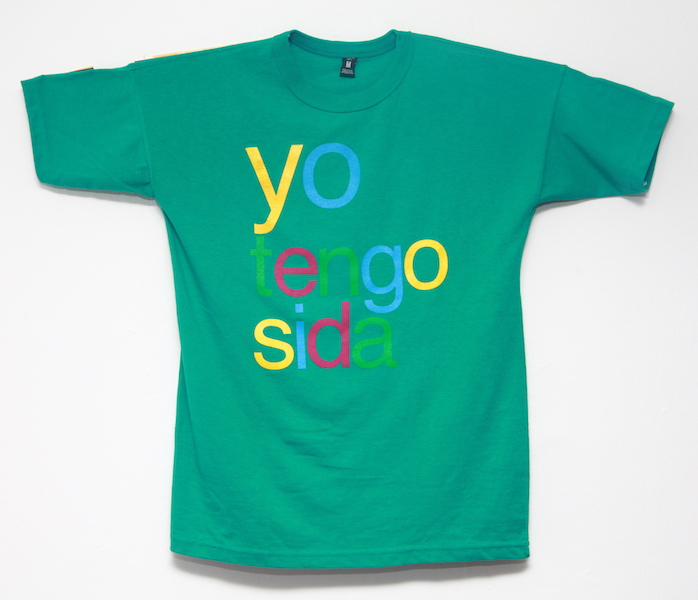

The 1994 t-shirt campaign “Yo tengo sida” [I have AIDS] by the Fabulous Nobodies—a fictitious advertising agency created by artist Roberto Jacoby and sociologist Kiwi Sainz—was one of the moments of greatest critical dialogue around the issue. Green, red, and blue t-shirts were printed with the title statement in equally bright colors and given out to friends and acquaintances. The thrust of the approach was to counter the alienation that people with the virus experienced. In those years, most of the official campaigns were about prevention and didn’t take into account the people who lived with HIV. Through the use of the first person and the t-shirt, the Fabulous Nobodies sought to create common ground around the virus, erasing the limits of the personal. To say “Yo tengo sida” [I have AIDS] is to preempt the policing of bodies. Even if just for a second, the affirmation negates the construction of stigma, beats them to it, plays politics with the clothed body.

Alejandro Kuropatwa, from the Cóctel series, 1996. Color photograph; 130 x 100 cm. Alejandro Kuropatwa Archive, Buenos Aires. Image courtesy of the artist

The historical narratives of the virus changed course in 1996, the year in which the 11th International AIDS Conference took place in Vancouver. Doctors called this event the “Conference of Hope” because they disclosed the results of a treatment capable of reducing the viral load to undetectable levels. If the AIDS crisis followed a specific timeline in each region, in the Global South the chronic turn of the disease set off a new struggle for the accessibility of medication that in some countries has not been resolved to this day. The first cycle of HIV began to come to a close on similar terms. At the end of the nineties, the country faced a social and economic crisis more severe than hyperinflation. Like every crisis, it endangered health in the face of growing poverty and a lack of medicine.

What will life be like now that we’re going to live?

This is the underlying question in the 1996 series of photographs Cóctel [Cocktail] taken by Alejandro Kuropatwa when he was able to access treatment.[7] Kuropatwa became one of the spokespeople de- manding that the state, displaced by the market, distribute and regulate resources for antiretrovirals. The impact of his photographs, participation in television programs, and publication of a commission in the newspaper with the largest circulation in the country produced a turning point in this history of images that seemed to close in on the logic of the field of art. In Cóctel, capsules of Nevirapina, Indinavir, and other drugs are arranged on a rosebud, next to a vase, among towels, in a pillbox, in the mouth of the photographer. This new life, connected indefinitely to pharmaceuticals, is shown as a luxury product enshrined in a perfect composition. At first glance, they seem taken from a shopping catalogue. Looking at them again, we see the vanitas of a virus that was starting to take another form in this part of the planet. The time of survival, of beating the odds, was now the time of chemical prostheses that provided immunity to the body.

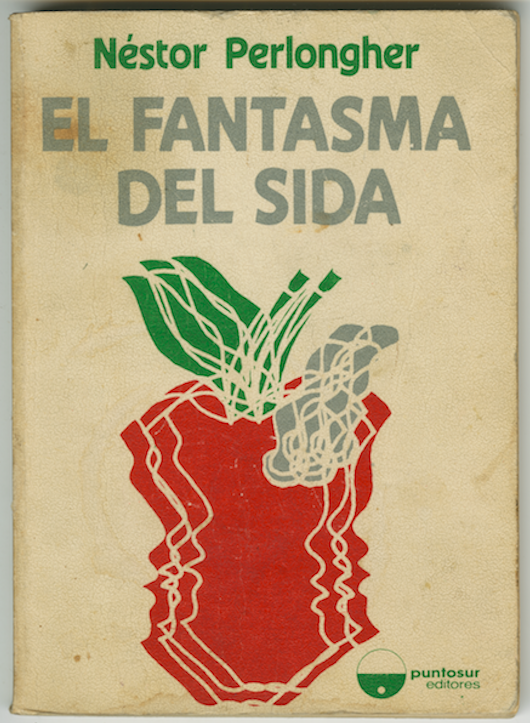

Years later that first installment from San Pablo took the form of a book: El fantasma del sida [The Ghost of AIDS] (Puntosur Editorial,1988).

Gabriel Giorgi, “Después de la salud. La escri- tura del virus,” Estudios, Revista de investigaciones literarias y culturales (Vol. 33, 2009): 17

I thank these data to Ana López, Cristina Schiavi, Marcelo Pombo and María Moreno, to whom I always turn to inquire into the memories of those years.

María Laura Rosa, Legados de libertad. El arte feminista en la efervescencia democrática, Buenos Aires: Biblos, 2014.

In the 1990s, Antonio Quarracino, archbishop of Buenos Aires, led a campaign against the pro- phylaxis which condemned homosexuals—he proposed that they live in a ghetto. Faced with the archbishop’s comments, León Ferrari decided to pay tribute to the condom in the exhibition De justicia y preservativos [Of Justice and Condoms] (1992) at Espacio Giesso in San Telmo.

Nicolás Cuello y Francisco Lemus. “‘De cómo ser una verdadera loca’. Grupo de Acción Gay y la revista Sodomacomo geografías ficcionales de la utopía marica,” Badebec (Vol. 6, 2016): 11.

On these ideas, I recommend reading Roberto Jacoby “Cocktail” (1996) in Alejandro Kuropatwa (cat. Exp.). Buenos Aires: Ruth Benzacar.

Comments

There are no coments available.