26.01.2015

Wandering through some of his most cherished literary references, Andrew Berardini finds freedom between genres, and reveals spaces of critical in-between-ness. If LA is a city that made itself up, why shouldn’t we art writers do the same?

Scratching paper is such a somber battle. There are no witnesses, no one else in your corner, no passion. And all the while, waiting outside, there are your blue spring, the very cries of your peacocks, and the fragrance of the air. It’s very sad.

–Colette, 1873

The peacocks wander freely here.

Their bark is off-putting, otherworldly, unbirdlike. The peahens, naked of their lovers’ iridescent tail feathers, moan with need throughout the long wet spring. Their aching calls fill the night air, already rank with night-blooming jasmine and exhaust, eucalyptus and smoke from the cheap cigarettes of the old Chinese men playing cards on milk crates under the streetlamps. In the mornings, incense breezes over the fence from my neighbor’s shrine. In the afternoon, the traffic of two freeways distantly hums. The mating hens call throughout.

Perched on the faded bungalows and on the porch rails of anonymous apartment complexes, on the cruciform power lines and blooming jacarandas, these weird exotics with their sexual howls and pornographic tail feathers don’t give a flying fuck that they are far from a jungle in India but instead, an ocean away, in the very center of a concrete cosmopolis of 15 million humans; or if they do, they make it work anyway.

—

The words wander freely here too.

They are ill-behaved, rebellious, unruly. They refuse containment. Always direct but never straight, they meander and arrive without schedule.

They hop the fence and fuck their neighbors. They adulterate and miscegenate. These words switch genders with a turn of phrase. These words are swingers, unless they can’t be bothered and then disappear as hermits and anchorites. They say whatever it is they want to say whenever they want to say it. They perform plays if moved by drama. They utter truth to power. They hide in fantasies. They lie through their teeth in fiction should that truth be a better lubricant. They criticize and report, they essay and they declaim. They enjoy a freedom on the margins of anything else, refusing to be nailed down.

This is a poem if they say it is. This is a prayer if they need it to be.

If the words decide it, as Henry Miller’s did, this is a gob of spit in the face of art.

—

The windows shiver with thump and boom of the rockets. Out my kitchen window, just over the lip of the hill past the half-built apartment building, its concrete skeleton lingering inchoate for years, I can see the fireworks bursting in air into ephemeral stars painted with light on the night clouds. With its vast parking lots and piercing lights and blue-capped army of fans, Dodger Stadium lies just on the other side and the fireworks make an after-game treat. Built over a demoed working class neighborhood like mine, few bother to remember it. In the other direction a sickle moon smirks above the 101, the white headlamps kissing red tail lights as the traffic coughs its way through the downtown towers to Hollywood and beyond.

Those skyscrapers are so close you can almost touch them. A wallpaper of power, each bearing the name of our overlords, mostly bankers. When the fog rolls in, the glass and steel appear and disappear like ghosts in the mist.

Lewis Brisbois. His name is not on the highest tower but it states it clearly and loudest, in bold white sans-serif. My friends and neighbors CC and Sterling joke about it all the time, “Lewis Brisbois can fix the world series, but he can’t fix his old man’s ticker” or “Lewis Brisbois may own this town, but he doesn’t own the heart of his own true love.” It’s just fun to say his name maybe with its wobbly roundness and hissing esses. We’re all poor, so maybe we like that his power can’t buy him everything. He is our Dr. T.J. Eckleburg in the Valley of Ashes, those blind eyes watching the tragedy of Nick and Daisy and Tom and the Great Gatsby play out into ruin. Lewis Brisbois beams into my bedroom window every night.

I have no idea who he really is and hope to never find out.

—

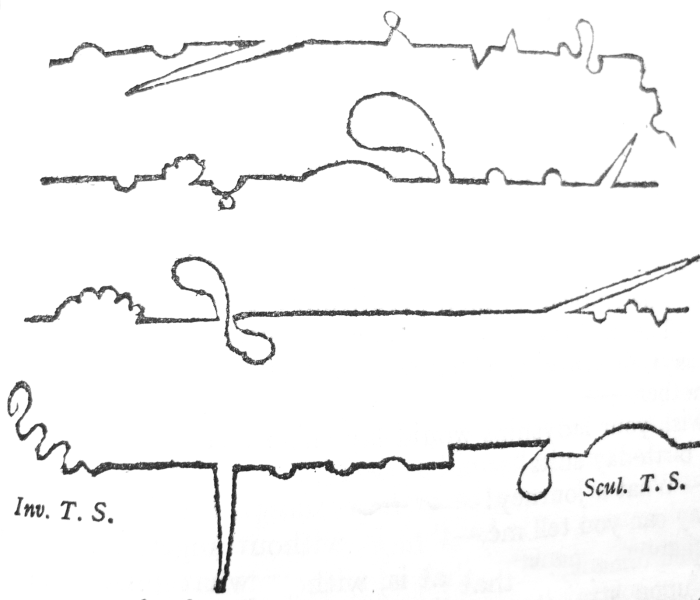

For some reason, I thought being a writer meant writing conventional novels. Characters moving along an EM Forster plot line from exposition to denouement in the linear rise and fall of a bell curve. Then I saw Tristram Shandy’s plot lines (puppeteered by Laurence Sterne) for the first four volumes of his memoir:

Linearity and realism and the Forster curve place a false shape and unnecessary rules on an existence that is neither linear nor realist. Past and future, distant events and quotidian concerns, memories and lacuna, imaginary threats and visions, hormones and desires and drugs thwart the straight line, the superficial sightlines of a faux-objective reality. In his autobiography, Tristram does not even make it to his own birth until Volume III.

—

There are no roads to the Stadium over the hill to the North, though you can bushwhack over the chain-link fences and scrubby grass down the steep decline to the Gate if you wanted. To the west, Sunset Boulevard, ribboned from the beach 22 miles away finally dissolves just past my house into Cesar Chavez Blvd and east into the East. Just beyond it is the 101 and its endless stream of lights. To the South is the 110 Freeway underpassing a few WPA bridges and down steep hills beyond lies Chinatown. Neon dragons and paper lanterns beckon tourists to buy pop snaps and flimsy fans, plastic anythings and greasy noodles. “A Bestseller Movie by Jackie Chan RUSH HOUR Was Shot Here!”

—

Is Frances Stark an artist or a writer? Is Chris Kraus writing fiction or theory or essay? When Anne Carson responds to Roni Horn in a work of literature so beautifully amorphous you might as well call it a poem, do I need to even call it a poem or art criticism or that Greek oddity, an ekphrasis?

I read Against Nature to be reminded how art can have a body that makes you lust and ache with every word. It’s less a novel for me and more a handbook for how to destroy oneself in the most delicious ways possible.

I read Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be? because for all its loose navel-gazing, it is real. Or as real as my people are able to manage, surrounded as we are with constant illusions.

Is it a memoir or a novel or art criticism or philosophy? I don’t care. The gentleman scholars of the Enlightenment can vivisect and classify, I do not need to murder the bird to admire its flight.

—

I move up and down Sunset everyday. My neighborhood lies near Echo Park, ruled once by street gangs and crooked cops. The corrupt police division has been dismantled and scrubbed. The street gangs still scrawl their names and claim their turf in loopy letters with old-fashioned angles, but they don’t run the neighborhood anymore either.

Few of the empty storefronts stay empty for long, each dreamer takes his chance. The eco-bridal store appears to open everyday. The restaurants with subtle signs and modern menus look crowded. But the shoe repairman in his Astrovan still parks next to the burrito truck even if the abandoned grocery store they neighbor now tenants a health food market.

But this is all just adjacent, a nearby place I can always visit but don’t actually live.

—

“The Hunger Artist” by Franz Kafka is the greatest piece of art criticism ever written, should we want to call it art criticism. It does not call itself anything at all but its own name.

The artist starves himself for wildly popular public display in the circus. Interest wanes, he continues to practice anyway. Forgotten almost entirely until his death, even then he is mostly misunderstood and unappreciated.

“I always wanted you to admire my fasting,” said the hunger artist. “But we do admire it,” said the supervisor obligingly. “But you shouldn’t admire it,” said the hunger artist. “Well then, we don’t admire it,” said the supervisor, “but why shouldn’t we admire it?” “Because I had to fast. I can’t do anything else,” said the hunger artist.

The artist can be nothing but be what he is. He isn’t any different than the jaguar that takes over the cage after his demise.

This noble body, equipped with everything necessary, almost to the point of bursting, even appeared to carry freedom around with it. That seem to be located somewhere or other in its teeth, and its joy in living came with such strong passion from its throat that it was not easy for spectators to keep watching. But they controlled themselves, kept pressing around the cage, and had no desire at all to move on.

The Hunger Artist did not practice for fame, the tameless panther will never flaunt its freedom for accolades. The jaguar’s freedom, undaunted by the bars, gives us hope in our cages.

Our attention is a kind of tether, but we need their freedom. When we escape, we will return with songs and poems, paintings and dance, each a rope back into the prison. Maybe somebody else will grab it and escape too.

But if you free a panther do not expect gratitude, she might eat you. It is only nature.

—

The neighborhood got the name “The Forgotten Edge” because it exists between so many larger neighborhoods and doesn’t really belong to any of them: geographically, ethnically, linguistically, spiritually. No through-traffic either and the city in the past often got confused of which police precinct served it, and so for years criminals had a hilltop fiefdom. This has all been sorted out now, but I still feel like I’m hiding in the middle of it all, with the closest most intense view of downtown. One of the few spots where a quasi-suburban Los Angeles really feels like a city.

I am in the center of everything and belong to nothing.

—

And where can the artist or his audience escape to? The walls are ethereal. They buzz with binary through digital webs. They shape each action and choice inside your head.

I think about this all the time.

The only answer I’ve ever found is in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. I repeat these words like a prayer.

And Polo said: “The inferno of the living is not something that will be; if there is one, it is what is already here, the inferno where we live every day, that we form by being together. There are two ways to escape suffering it. The first is easy for many: accept the inferno and become such a part of it that you can no longer see it. The second is risky and demands constant vigilance and apprehension: seek and learn to recognize who and what, in the midst of the inferno, are not inferno, then make them endure, give them space.”

The space I find is amidst inferno is not inferno. It is here in this city of changes. It is a forgotten neighborhood where the peacocks roam wild. It is a house on a hill, a table in the kitchen, and a white page for me to fill with whatever I desire.

—

My landlord is the grandson of my grandfather’s landlord. Though it’s mostly Chinese and Mexican and the weird racial brew of young aspirants, my neighborhood was once working-class Italians. I am almost the last in the neighborhood who can trace his lineage to those early immigrants. There is another though. He runs the Eastside Market, a deli beloved by cops and firefighters. I read somewhere he’s from the same village as my family but I’ve never met him.

None of this matters, except that it makes me feel a stillness that roots me into the past while the loose drift of a transient civilization washes around me. The house where my grandfather and mother raised my father was torn down fifty years ago for a parking lot that has since been abandoned. I am from somewhere, and this gives me some comfort, but it doesn’t mean anything. I easily trade tradition for freedom.

But this is Los Angeles and so am I.

We both make ourselves up as we go along.

Comments

There are no coments available.