22.06.2015

Starting from his research in the history of artists organizing processions and parades, the São Paulo based curator Tobi Maier asks: How do objects and costumes employed during these rituals move between the utilitarian and the symbolic? How do they mediate in public practice? What are these performative events leaving behind beyond their unique temporality?

“I dream of the day when I shall create sculptures that breathe, perspire, cough, laugh, yawn, smirk, wink, pant, dance, walk, crawl…and move among people as shadows move along people”, the Filipino artist David Medalla once stated (1). It is this ambiguity between moving subjects and objects that interests me in the research on processions and parades organized by artists. How do subjects and objects merge while they are in process of activation and what stays behind after they have been employed for presentation, how are their “residues” presented within exhibitions and can they not only fail to convey the festive spirit they were supposed to carry, once they were taken from the street and into the exhibition space?

When I think of processions designed and organized by artists, it is not only the geographical and institutional contexts that ought to be considered, but also the level of engagement of the performers, the props and costumes designed for the occasion or the music that accompanies their ephemeral staging. It is about the ways by which visual artists reimagine street theatre and the dynamics of relationships between subjects and objects in space. French philosopher and anthropologist Bruno Latour says: “There is probably no more decisive difference among thinkers than the position they are inclined to take on space: Is space what inside which reside objects and subjects? Or is space one of the many connections made by objects and subjects?”(2) There seems to be a lot of thought going into the relationships that we as subjects retain with objects that surround us and that we carry through space.

Processions and parades, albeit ephemeral events, leave traces behind: objects or documentation. Most often these take the form of documents that were generated during a preparatory process (permits, correspondence, etc.) and lens based works such as video or photography that take on the role of documentation, up to an extent that the “photographic document is a replacement of the object or event” not merely a record of it, as curator Okwui Enwezor has stated in the catalogue text for his exhibition Archive Fever at ICP, New York, on view during 2008 (3).

While technology has enabled us to retrace the steps of ephemeral events in more detail, artists have become accustomed to produce immanent works from the transient. Art historians on the other hand have lamented the scarcity of documentation of some elements of Renaissance artists’ performance. Sir Kenneth Clark wrote, “In studying the architecture and even the painting of the Renaissance, we must always remember that one whole branch of each is almost completely lost to us—the architecture and decoration which was designed for pageants and masquerades.” Some attempts were made to create a record of these works, particularly triumphal processions honoring the mighty, in the form of commemorative books especially prepared for the occasion, which reproduced the principal motifs devised by the artists (4). This practice is not dissimilar today, even though we no longer speak of “commemorative books”, instead of artist’s publications, magazines or catalogues plus a wealth of online media that instantly feed us with images and video impressions from events around the globe.

What are artist’s considerations when thinking about the esthetics these “residues” (photos, or for that matter video, or costumes /dresses) leave behind in an exhibition space once the performance has ended? How does the work change, when it is not experienced first hand? I’ll concentrate here on recent performances by Arto Lindsay and Luisa Mota that I witnessed here in São Paulo and another one I worked on together with Brazilian artists f.marquespenteado in Torino.

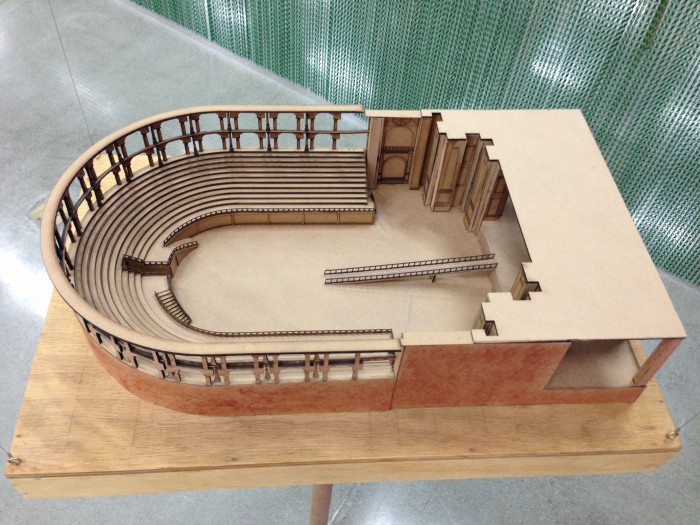

One of the most active figures in the Brazilian art scene when it comes to processions has been musician and artist Arto Lindsay. In an extensive interview I conducted with him last year he stated, “when you parade for four or five hours, it’s a transformative experience, it’s ritualistic in the broadest sense of the term. You come out differently on the other side.”(5) Lindsay has conceived parades for Performa festival in New York, Portikus in Frankfurt am Main, the Venice Biennial, the carnival in Salvador da Bahia and during Art Basel Hong Kong. For São Paulo, Lindsay organized Parada Pedra during the 33rd Panorama (2013), the biannual exhibition of contemporary art that is organized by the Museu de Arte Moderna (MAM) in São Paulo. During the procession, which took place in the city center commercial passage Nova Brandão, participants carried scale models of stages and iconic houses, the Casa Malaparte (Capri) and Teatro Farnese (Parma). The curatorial idea behind the 33rd Panorama had been to reimagine a possible future for an itinerant MAM, an institution designed by Lina Bo Bardi and squeezed under an Oscar Niemeyer designed passage in São Paulo’s Ibirapuera Park. Thus Casa Malaparte and Teatro Farnese were representative for an utopian architecture that could host a new MAM and within this particular local context they were hinting towards a variety of abandoned iconic buildings in the city center that could be made fit to host exhibitions (Cine Marrocos and others around the Largo Paisandu neighborhood in downtown São Paulo). The performance with the main protagonists (the scaled down architectures from Capri and Parma) referred back to the bohemian past of São Paulo’s city center and its potential future. Once the performance ended the sculptures were put on display inside the museum. Few people however seemed to have understood their meaning, a wall text being the sole attempt to connect them to what only a small public had witnessed days before.

For the 2013 edition of the São Paulo performance annual festival Verbo, Portuguese artist Luisa Mota staged a procession entitled Invisible Men, departing from Galeria Vermelho and along Avenida Paulista. For Mota the medium of “parade, the procession, the protest, a group of individuals walking, marching together is a powerful source of agglomerated faith/belief, energy on something that unites them into one. […] The fascinating aspect to me (says Mota) is that the material is alive and breathing, having a mind of their own and their own purpose, their own life […]. Together you create a choreography of symbols, a ritual, you begin to create a language that communicates a message to other people, because certainly people resonate something into one another.”(6) Mota makes no distinction between objects and documentation and states that she retains remnants, objects, costumes; that photos and videos are also to be understood as works, as anthropological artifacts, meant to be shown and used as such.

Most recently Brazilian artist f.marquespenteado staged Three Novels (2014), a performance at Per4M, the inaugural performance section at Torino’s Artissima fair in November 2014. Three Novels presented fictional stories that involved three different men (Sean the writer, Jonas the photographer and Javier the architect), which are described through the lenses of a narrator (the artist himself), him being the three character’s ex-lover. Three Novels started with a short procession led by the artist himself continuously ringing a small crystal bell, followed by three actors (personifying the three lovers) who were carrying drawings and embroidered textile works from the booth of Mendes Wood DM gallery to a stage that hosted the Per4M section. Three panels had been installed there, which in a Warburgian fashion combined material collected by the artist over the last 20 years at London flea markets, or were culled from magazines, maps, catalogues and instruction manuals of all sorts. Depicting nature sceneries, literature covers (Wallace Hamilton’s Christoper and Gay: A Partisans View of the Greenwhich Village homosexual Scene, for example) or erotic photographs, these offerings were combined with drawings and hand written notes that together represented the universe of each one of the three lovers. Many of the works presented in Torino travelled to São Paulo after the performance and were presented in the homonymous exhibition at the gallery. Thus in these “highly authored”(7) performance projects, these ‘leftovers’ are carefully conceived in advance and often preserved for an afterlife (alongside documentation or not) in an exhibition context.

In other participatory projects – take the São Paulo carnival for example with its many artist conceived blocos – costumes and other elements are often created in collaboration and yet discarded after the actual event has taken place. For the collectively authored rufos Y bufos bloco a group of artists, designers, writers and architects met for a month in a city center apartment conceiving costumes and props, few of which survived the actual procession in early March 2015. Another example here would be Brazilian artist Ricardo Càstro’s series of ‘abravanaçoes’ events, for which the artist creates costumes and accessories from a palette of materials and colors, distributes them to friends and volunteer participants with whom they remain throughout the street processions and afterwards.

The participatory walks organized by different artists here most importantly reflect an idea of playing the city, of activating and manifesting a presence in public space. Yet, it is an idea of play that is not naïve or innocent, rather one that is geared towards an active belief for engaging the other, experiences of walking that are not merely in tune with the Situationist idea of lone dérive, but constructed on concepts of agency.

This agency creates meaning and is built on each participant’s experiences in a collective effort of exchange. As the American philosopher John Dewey has noted: “for while the roots of every experience are found in the interaction of a live creature with its environment, that experience becomes conscious, a matter of perception, only when meanings enter it that are derived from prior experiences.(8)

Thus when walks and cartography projects carry an inherent semantic, corporal, tactile or visual component, an architectural framework or a socio-political agenda, they can engender meaning that helps us to depart from the representative question “Where do we come from?” to a participatory one, one that is geared towards the future namely: “Where are we going to?”

For Terremoto, São Paulo in May 2015

Notes:

(1) Signals 1, no. 8 (June-July 1965); reprinted in the catalogue When Attitudes Become Form, Kunsthalle Bern, 1969, unpaged

(2) Bruno Latour, Spheres and Networks: Two Ways to Reinterpret Globalization in Harvard Design Magazine 30, Spring/Summer 2009, p.142

(3) Enwezor, Okwui, Archive Fever, Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art, International Center of Photography, New York, Steidl, Goettingen, 2008, p.23 [accessed via http://bookchin.net/feeling/readings/photography_between_history.pdf]

(4) Gregory Battcock and Robert Nickas, (ed.) The Art of Performance, A Critical Anthology, 1984, p.15 (Renaissance performance art took most of its forms from the highly ritualized society of the Middle Ages when church processions and feudal formalities such as jousts were anonymously planned. Individualism was responsible for contaminating these forms with personal interpretations and for awakening a lust for fame that naturally led the men of an age obsessed with antiquity to those ancient metaphors for personal greatness, the triumph and its counterpart the triumphal arc. P.20)

(5)In ArtReview, London, September 2014, p.104ff

(6) Luisa Mota in email conversation with the author

(7) Claire Bishop Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, London and New York: Verso, 2012 p.39

(8) Dewey J. in Ross, S. (ed.) Art and its Significance, New York: State University of New York Press, 1994, p.218

Comments

There are no coments available.