A dialogue between Ruth Estévez and María Berríos about the Valparaíso School of Architecture and the exhibition «Del Tercer Mundo» held in Havana, Cuba, as well as their value as historical landmarks for the concept of collaboration and the questioning of authorship.

The Unforeseeable Result of Mutual Exposure

A paradox lies at the center of our late capitalist society: the production of a hyperindividualist subjectivity that emphasizes personal experiences is only possible due to ongoing cooperation within this system, which in turn is the product of an exchange of inherited knowledge and techniques that are the foundation of our society.

Within the sphere of art, collective labor—both in works that involves group participation in its conceptualization and those where the viewer/spectator participates in the work—has been extensively studied, and artists have elaborated a range of action models in recent decades to carry out collective work. But collectively produced artwork as we understand it today is without a doubt a reverberation of a historical process in which artistic discourses were marked by (or reflected) contemporary social upheaval and times of crisis, like the student movements of 1968 or the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. These situations redirected our modes of operating in opposition to hegemonic power through events that proposed new ecologies of knowledge and ways of diversifying power, problematizing the extrapolation between individuals and collectivities.

Ruth Estévez: María, in recent years you have carried out numerous studies regarding collective creative processes in Latin America. In particular, there are two cases that seem especially relevant to me, although their origins and time frames are different. I’m interested in your research on the work developed by the Valparaíso School of Architecture in Chile (1952–present day) and the legacy of its pedagogical methodologies, as well as the work you’ve done in collaboration with the artist Jakob Jakobsen on the Havana Cultural Congress (1968) and the exhibit Del Tercer Mundo. Despite its radicality, we know very little about this project except that it was held at the Pabellón de Cuba, a key building of Cuban modernism.

María Berríos: As you mentioned, these are very different projects in a number of respects; however, they are connected through collective practice. In both cases, there is a questioning of individual authorship, as both projects offer a critique of the notion of private property. They also both share a pedagogical component connected to the epistemological value of experiences and everyday life as a space for learning. However, the routes each project has taken and the ways in which they arrived at these conclusions are distinct.

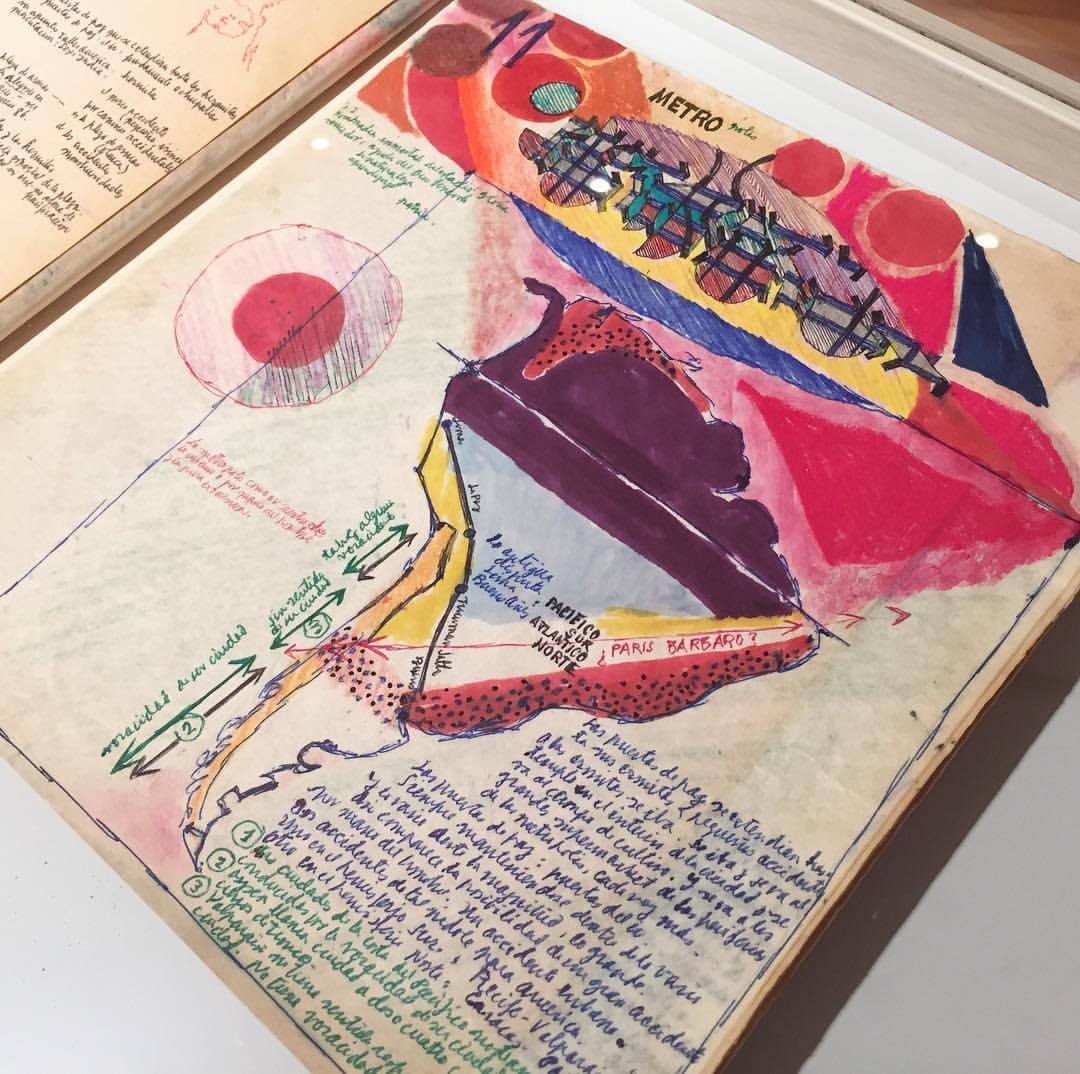

The Valparaíso School of Architecture is a project concerned with life, work, and scholarship that was born in the deeply conservative context of Chile in the early fifties. To suggest that architecture couldn’t be taught in a classroom and rather required one to go out into the streets to explore, observe, and participate in “intimate” urban life was a radical thought prior to the subsequent boiling point and occupation of public space. By the late sixties, the Valparaíso School of Architecture had already been engaging in collective labor for two decades with a group of young architects and poets who had moved to Valparaíso. At that time, the port city had expanded topographically into the hills with new vernacular structures that challenged the normal organization of Latin American cities according to the Spanish grid. Members of the school thought of the city of Valparaíso as a laboratory for collective experimentation and architectural self-learning.

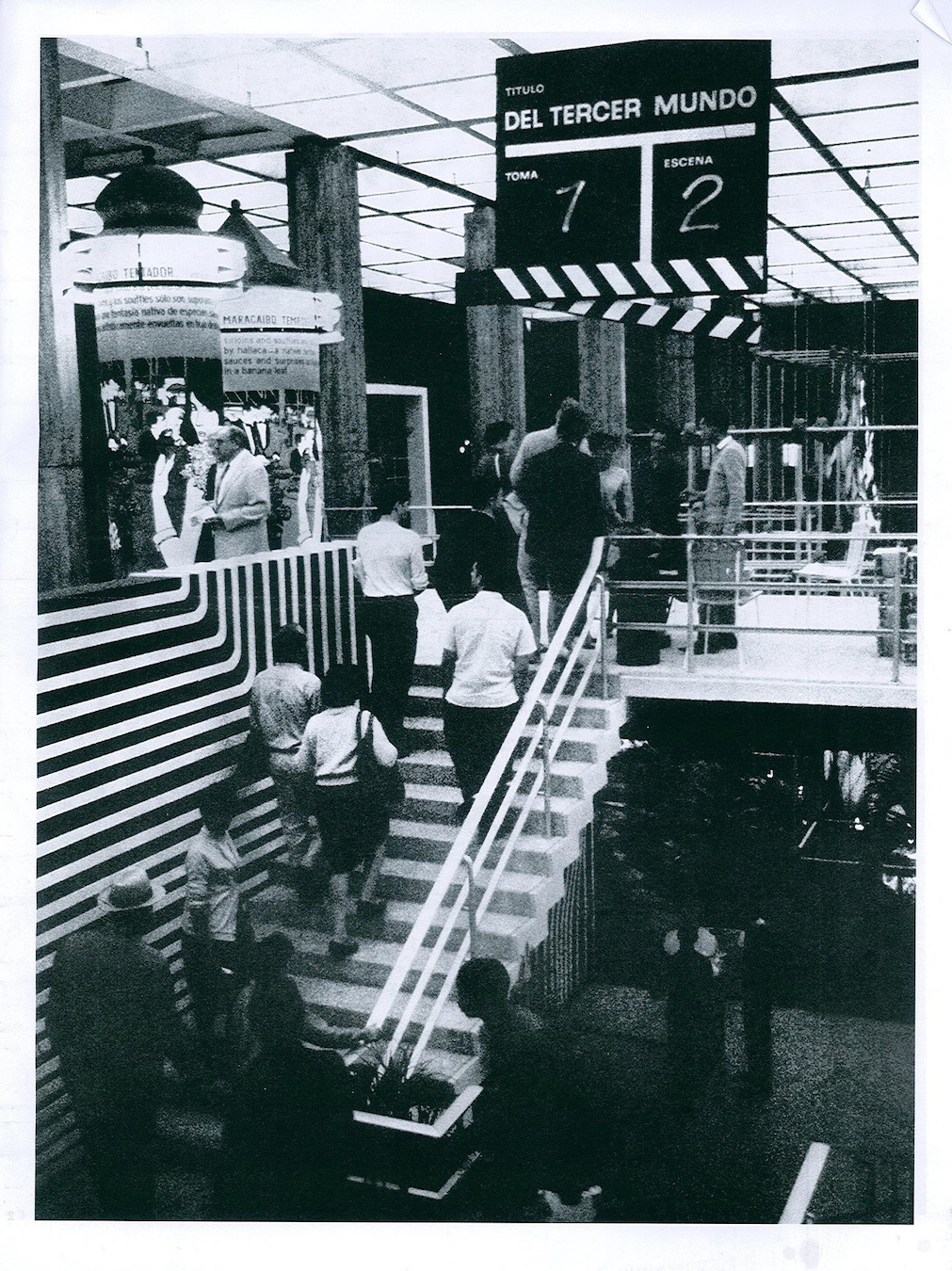

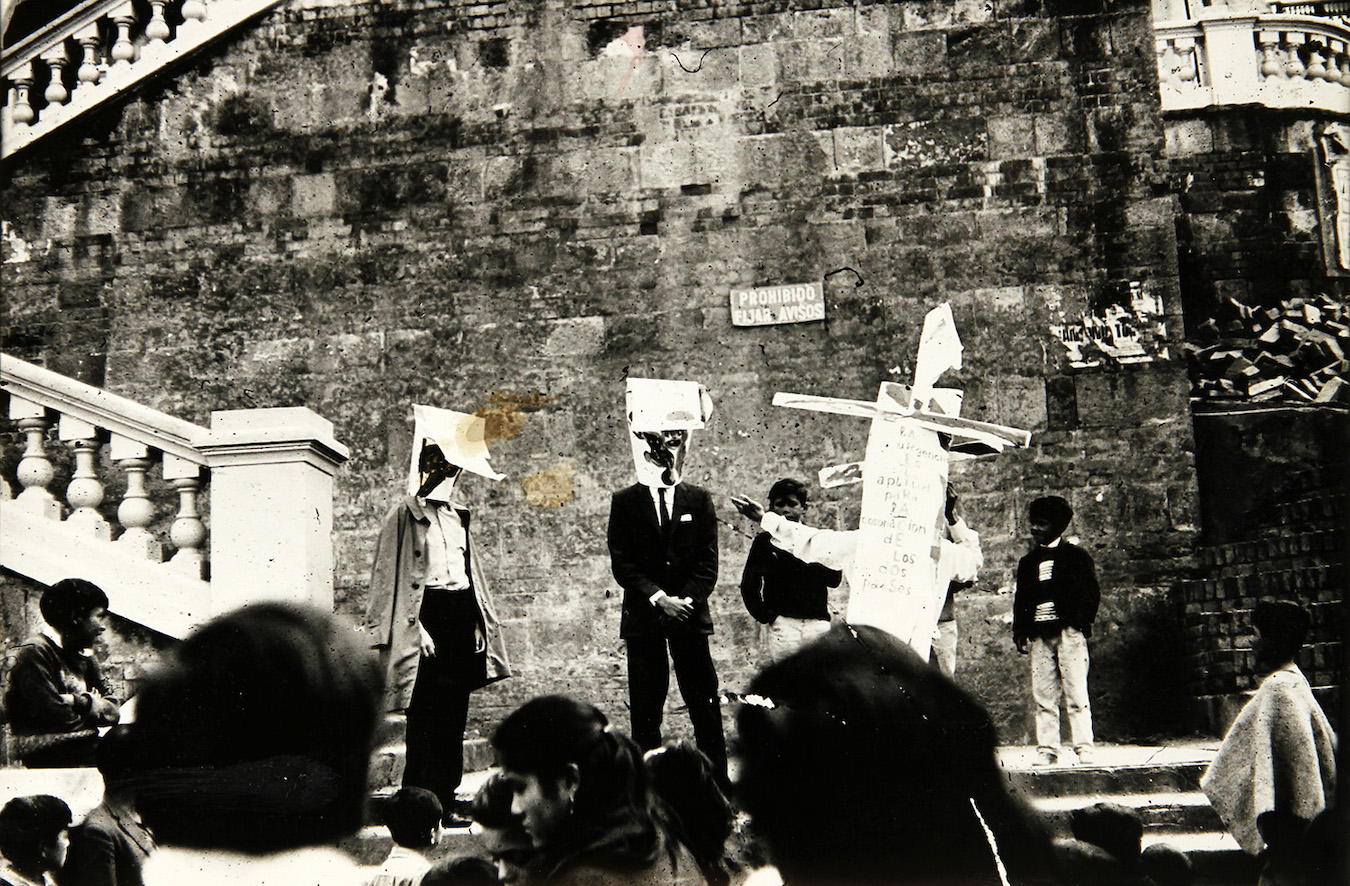

In this sense, there is no possible comparison with the group of young Cubans who decided to work collectively for a little under a year on the show Del Tercer Mundo [From the Third World]. Nevertheless, it could be said that the true project of life, work, and collective living was the Cuban Revolution itself, or more precisely, the 1968 Havana Cultural Congress that was initially conceived of as a congress to debate problems confronting the Third World from a cultural perspective. Architects, designers, editors, sound engineers, electricians, carpenters, and typesetters participated in developing the show’s concept as part of this cultural congress. The exhibition’s format was inspired by cinematographic models; its organizers aimed to tell a story by creating a narrative-based spectacle that would guide viewers through the space. They created a soundtrack to mobilize viewers from distinct “zones” that traced out the history of colonization in the Third World: the exploitation of natural resources, the subsequent hunger and misery, revolt and rebellion, the imperialist response, and then the revolution. All of this was illustrated with live animals (two llamas and a lion), neon animations, a detourné Tarzan film (instead of Tarzan pursuing the black indigenous people, they pursue him), a mural made up of comic strips in light boxes with popular characters (including Superman with an Esso logo on his chest), and an enormous camp version of Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam with flickering light bulbs.

The show was installed in the Pabellón Cuba, which, half-building, half-tropical garden, is one of the most emblematic buildings of Cuban modernism to have been built after the revolution and was the perfect setting for the story told in Del Tercer Mundo: the garden functioned as a set for the exuberant nature of the colonies, in which white men positioned themselves in a myth defined by the absence of a population capable of appreciating and exploiting the richness of “nature.” The cinematographic model not only followed in the revolution’s conception of cinema as an educational and awareness-raising tool, but it also saw cinema (as well as theater) as the product of collective labor.

RE: In the case of the Valparaíso School, in what sense did collective labor “contaminate” knowledge and diverse production models to reconfigure these types of knowledge?

MB: When I think specifically about the first two decades of the school’s work, it seems to me that their notion of the collective is not that closely related to what we understand today as interdisciplinary. In fact, they believed in disciplines. For example, they insisted on distinguishing the group’s artists and architects. But they did believe that architecture had a lot to learn from art—there were several artists in the group—and from an early point they were concerned with organizing exhibitions (for example, they were the first group to exhibit concrete art in Chile). They were always interested in collaborating and learning from other disciplines, not just art but also music, philosophy, as well as aeronautics and mathematics. Nevertheless, for me the most experimental and relevant work they did was concerned with architecture and poetry. Architecture cannot be reduced to its buildings, rather it has to do with a poetic form of dwelling, with a way of being in the world. This is connected to the school’s notion of the collective that was at one point defined in terms of “the risk and courage to make worlds.” The collective in this sense was seen as the unforeseeable result of mutual exposure. Their pedagogical position lies in part in explaining their work to one another, but also in exposing themselves to a context, to the world around them. Seen in this way, the collective can be understood as a methodology for self-learning, which is radical in itself because of its relationship to autonomy: free from, yet simultaneously conscious of, the supposed “sources” or required routes. The Valparaíso School emerged and developed in a very provincial and isolated country, and their expanded understanding of architecture as a means of intervening in this context and of transforming it contained a necessary dose of irreverence and constituted a form of emancipation.

RE: There’s no doubt that the Valparaíso School attempted to do things on its own terms, while attempting to think about the history and future of Latin America internally, instead of from a foreign perspective.

MB: It may be that this “doing things on its own terms” was a necessary condition of doing work in Latin America at the time. Not in the sense of self-absorption, quite the opposite: there was a drive to be more up-to-date, in the “here-and-now,” and to act not just on a local level. The Valparaíso School made several efforts to establish important connections outside of its immediate context. Its members attempted to create a branch in Europe and indeed several members of the collective moved to Paris in the late fifties and were in contact with Latin American expatriates living there, including many connected to the Argentine movement Madí. They also established multiple networks throughout the Americas, creating links to people who worked in architecture, critical urbanism, and radical pedagogies. In Mexico, for example, they had contact with Ivan Illich and Valentina Borremans, and the Centro Intercultural de Documentación (CIDOC) dedicated one of its dossiers to the role of the Valparaíso School in the 1967 Chilean University Reform. With these networks, they sought to learn from one another and at the same time make their proposal for a new architecture and their “New World Poetry” known. Collective work was not only a form of collaboration, but also a means of learning from the world while bypassing the hegemonic institutions that controlled access to the metropolitan centers of the dissemination of knowledge.

RE: In the case of the exhibition Del Tercer Mundo, the critical position its participants adopted with regards to the concept of “Third World” started from the disadvantages of the imposed hegemonic, universal culture that had emerged from Europe and the United States. Rather than building their own context, the idea was to reverse or comment ironically on an imposed context.

MB: The young Cubans who put together Del Tercer Mundo were up-to-date with what was happening in the world, especially in terms of artistic practices and pop. They had a critical perspective on how metropolitan centers functioned and their efforts sought to appropriate the notion of “universal” culture. They defended the Third World as a political movement in order to disconnect it from a purely geographical identity as property fought over by multinationals (it is worth remembering that at this time, several representatives of the Black Power movement in the US identified as being part of the Third World, as they were oppressed by the same imperial power).

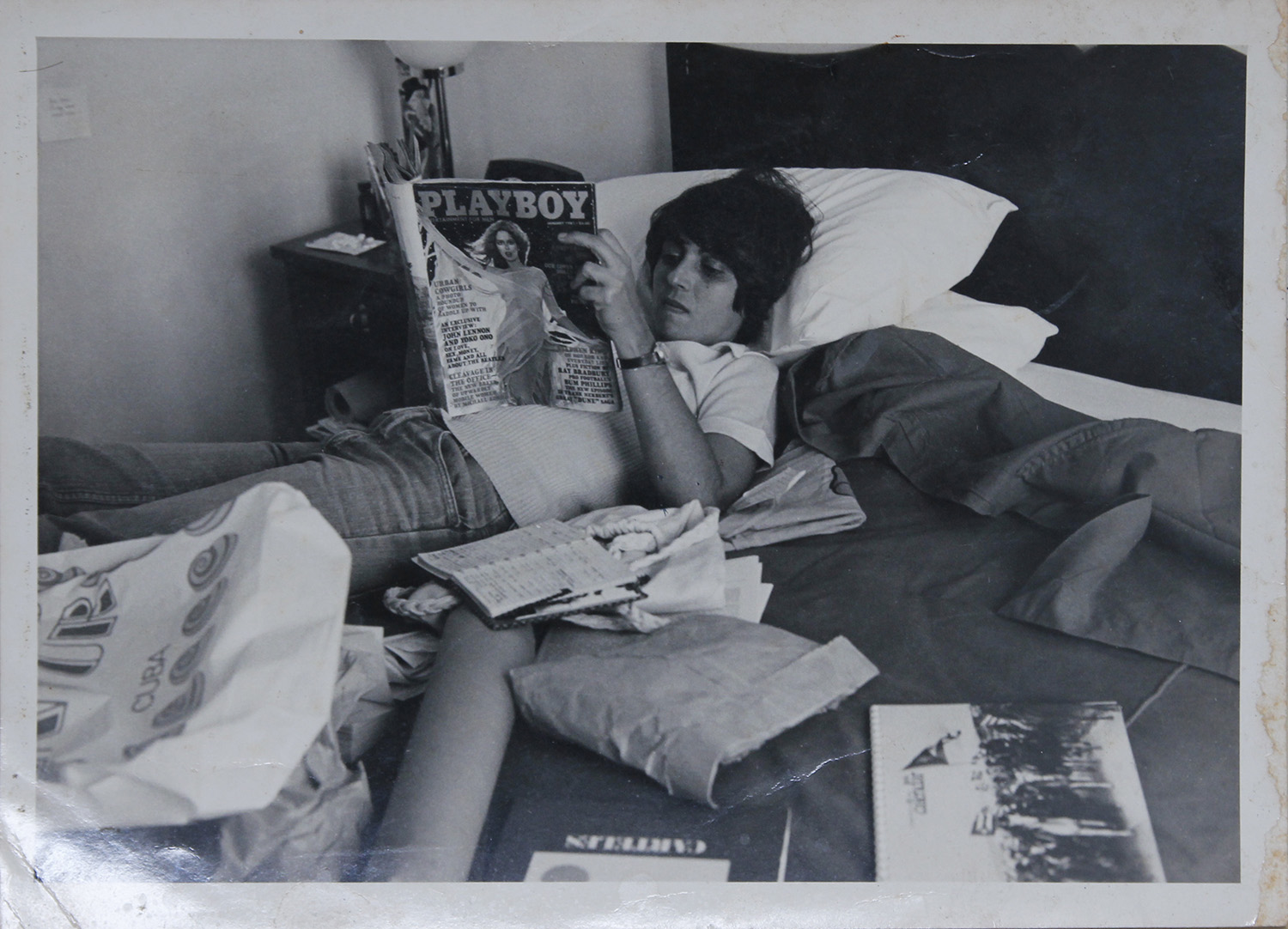

For the group that set up the exhibition, defending the Third World had to do with the right to use any tools necessary to achieve their goals: not so much in order to reverse something irreversible, but rather to appropriate the tools to construct it as their own. They used everything to put together the exhibition, without considering whether US imperialism or the artistic elite would claim it as their own. There is a photograph of a young woman, Rebeca Chávez—one of the show’s organizers—flipping through Playboy, looking for material for the exhibition. This image challenges the stereotype of the young revolutionary inspired by socialist realism. Additionally, they had a critical stance regarding the “collective,” and they framed their proposal in opposition to one of the most important art exhibitions in Cuba, the Salón de Mayo, which was inspired by the Paris Salon and was also held at the Pabellón Cuba in June 1967. Organized by Wilfredo Lam, the central piece of art in the international exhibition was a “collective” mural made up of small segments each painted by one of the invited artists. The young people who set up Del Tercer Mundo noted that putting numerous individual works together does not imply collective labor. In their eyes, the collective was defined by the creation of something new that does not belong to anyone, but rather to everyone.

RE: I’m interested in how projects that emerged in a specific moment and under concrete political circumstances are presented and understood relationally today. It’s not so important to show these projects in an archival format or give them visibility as projects produced from the “margins.” I believe it is urgent that we understand how their formulations and methodologies of work can be applied to the present and that we evaluate their relevance today.

MB: I choose to research certain practices because I feel that they bring to life something that has not been articulated beforehand and that forces us to rethink the present, and above all, the future. These practices help define the direction of our future.

For its part, the exhibition Del Tercer Mundo made a complete break with what was understood as propaganda art, complicating its relationship to educational art and exploding the notion of a natural division between the “pueblo” (working class) and the world of “high culture.” It was one of the first global exhibitions (visited by around two hundred and fifty thousand people) because it was a success among the intellectual and artistic elite who attended the congress, but also among Cuban students, workers, and housewives. The exhibition was as popular as El Tren de la Cultura in Chile, which was a precedent and seed for the Museum of Solidarity in Santiago. These are projects that demonstrate that experimental art or “high” culture cannot be popular by definition. The exhibition Del Tercer Mundo featured well-known images universally recognized as high culture, to draw people in, based on an understanding that the familiarity of these images constituted a popular language. The show was important because thousands of Cubans visited it and felt it to be their own, a part of their history.

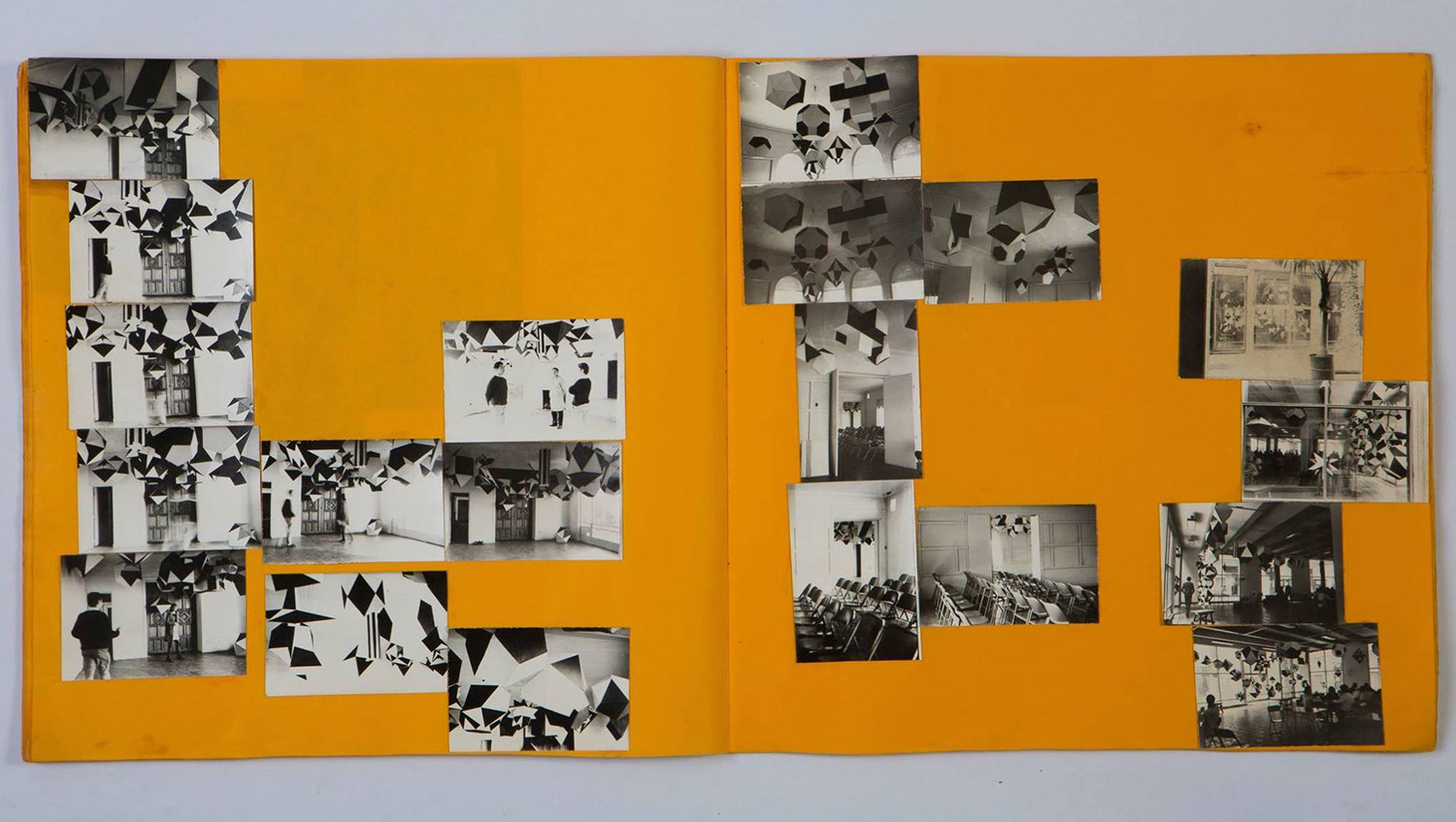

On the other hand, the extraordinary exhibition held by the Valparaíso School in the basement of Chile’s National Museum of Fine Arts to celebrate its twentieth anniversary in 1972 involved similar ideas about the relationship between mounting exhibitions, storytelling, and creating spaces for socialized learning. The exhibition was audacious for the era—it was installed in a half-built space—and it presented a manifesto-story of the school, written and drawn with white chalk on fifty-nine blackboards that lined the perimeter of the space. The exhibition was visited by students who went to transcribe the texts, copy the diagrams, or simply sit in the chairs set out in the space to observe the blackboards or read the newspapers and publications lying on a table. The museographical innovations that the collective proposed (specifically the treatment of the exhibition space as a public plaza, a space to converse with others, and, simultaneously, an open classroom) are ideas that are still discussed today.

RE: This collective optimism was in part obfuscated by the dictatorships that restrained freedom of expression, as well as neoliberal policies that exacerbated our understanding of selfhood. But questions around collaboration and group work return constantly in different formats, as can be seen in such biennial programs as the 31st São Paulo Biennial or the most recent edition of the Istanbul Biennial, or models for art centers, such as CASCO in Utrecht, which continue to articulate new forms of collective creation, interaction, and production.

MB: Perhaps I would question the existence of a “past optimism.” I am reticent to accept a certain vision of an optimistic-utopian past versus a pessimistic-realpolitik present because such a lens demarcates these collective practices as naïve or unrealistic. On the contrary, I believe that they were very critical to their present moments and concerned with identifying obstacles of their time.

I agree that there is an element of tokenism in discourses of “the collective” in today’s art world, but I also think that the idea of working alone, especially in art, is an autocratic fiction.

Art history is based on the creation of values and frameworks, be they those of the “big name artist” or “big name curator,” but I think these are decadent and false categories. There’s nothing more annoying than seeing the stand occupied for the umpteenth time by a super-macho voice drowning in overconfidence, responding to questions that are always rhetorical and without any interest in connecting with the world. In contrast, I feel relieved when the work shown involves risk and vulnerability. It depresses me that art schools, even those with “experimental” curricula, structurally reproduce the notion that the artist has to “make a name” for themselves. Obviously, this is a caricature that simplifies complicated issues, but I think it is important to recognize that art is one of the few spaces that allows for collaborative experimentation.

Moreover, it is simply a more sustainable way of making things. Personally, I work collaboratively not because I find it to be ethically superior, but rather because it is far less boring. I learn more, and I respect and admire the people with whom I work and learn.

Comments

There are no coments available.