The following anonymous text, signed by the names of those who chavism has taken their lives, reflects about how authorship in the regime articulates and legitimates a ravenous inhumanism.

The Bolivarian experience, with its continuity solution, set out to prove it: the death of the author and the survival of authoritarianism. In broad strokes, the controversy surrounding the legal aspects of the signatures found on the moribund commandant’s last decrees, including logical suspicions of forgery, is back in play again. Alongside the regime’s authoritarian drift, there is a clear need to manage grief regarding the death of the author.

We must urgently wonder if authorship does not function as a pillar of authoritarianism; discourse, signature and similar signs as a reservoir of potestas.

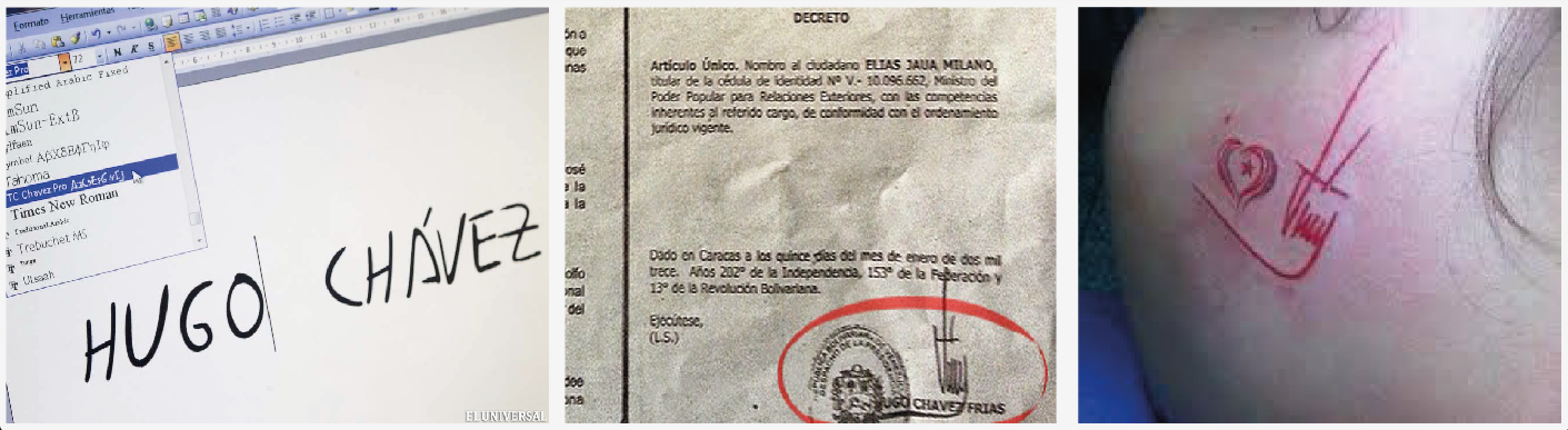

Otherwise, it will be the function of the author itself that will buoy authoritarianism’s soul: authorship as a repertory of power, stored up in a re-appropriable signature, a mask made graphics, able to transcend the death of the sovereign’s body and deify him. This has become more visible than ever in the Venezuelan State, where speaking of ‘signature’ means necessarily speaking of an invocation. Dead, comatose…to whom to ascribe the authorship of the decrees that shored up this cruel, pathetic succession in pursuit of an ever-more chronic authoritarianism?

*

Parades, uniforms, flags, monuments, banknotes and coins, museums and mausoleums, anthems and all manner of signs: the old thesis of State-as-artwork regains all its freshness in the landscape that now concerns us. Venezuela’s first democratically elected president, Rómulo Gallegos, was a literary writer. But as often happens with isms, we can also say Chavism is an aesthetic movement, in its particular case founded on a total eclipse of the artist by the sovereign. All artists eclipsed by the sovereign: an absorption effect on all authorship, by authority, that explains the devastation of the Venezuelan cultural fabric, but also and above all the decline of the political and the human in general. A State seized by mediocre artists: degradation by aesthetic means. Agitprop voodoo, able to make contemporary art’s most sadistic or macabre reveries a mere rehearsal of evil. The genealogy of the figure of the artist as political tyrant –we’ve been given notable manifestations since before Nero and even after Chávez– old attest to different modalities and formalizations that power as an aesthetic pleasure has moved into, to date. The soft-power era demands insubordination of the tyrant; Chavism stands out in transmedia narratives of the NetArt happening. Venezuela is thus understood as the materialization of a totalitarian artwork, a mix of the popular and new technologies, contemporary and archaic languages, plus animist religion, expressed in the swagger of comments and shares, dystopian literature in fragmentary tweets as installations made of human bones in Miraflores basements: landscape painting in coltan and bone. Nero was fond of executing prisoners during theatre performances. Chavez, in turn, was more about doing TV shows with officiants dressed as scientists, broadcasting nighttime exhumations, live, on the national network. The skeleton of Simón Bolívar (el Libertador) as a vehicle for definitive ritual consolidation of what we should have long ago started calling ‘necrocracy’: a necro-government where power, like petroleum or the spirit of votes stolen from the dead, oozes up from the ground.

*

The giver of life and housing, God and Architect, Father and Love, we suppose Chávez died signing his name. It’s purely logical given the number of signatures he had to put down. We imagine his last living breath was consigned to some ballpoint pen, moving on to the keyboard with the creation of the digital signature or typography, to end up in the tattoo artist’s bloodied needles and who knows what else. Chavism would seem to claim authorship of all Venezuela for Chávez, along the skin-façades-territory continuum. Life and housing, death and tombs. The ubiquitous, omnipotent and omnipresent signature of a necrophiliac god. The housing fills up with future cadavers, the cemeteries dumping out bones and at the morgue, ever more bodies, tattooed with the signature of a god, putrefying. Because Venezuela, among the world’s most violent countries, tends to take first place. To whom to ascribe the authorship of countless crimes and murders that proliferate in the living conditions Bolivarianism has created? If the State consists of a monopoly on violence and in Venezuela the State is omnipresent, will it not publicly display the copyrights of its more than 28,000 annual murder victims? After the 2002 coup attempt, Hugo Chávez signed off on a budget freeze for several law-enforcement agencies, forcing the appearance of a black market in weapons whose growth has paralleled his signature’s hyper-proliferation across the nation, in the city and the country, everywhere from skins to screens. To date, both pen and lead have been unstoppable; a president’s signature can set off a chorus of hammers, in slums and jails, on sidewalks and in shopping centers… they tend not to be salutes. It’s a signature that keeps on proliferating in stolen gestures and strokes, sustaining the continuance of the thanatical, its related signs magnified.

The gross usurpation of a president’s signature, identity or soul would be scandalous anyplace else on earth; but here it’s understood as a quasi-religious celebration. Venezuelan authoritarianism largely emanates from the authority of Hugo Chávez Frías, in his mystical elevation. Not for what he did in life but for what he does, deified, as a dead man. Because the author’s function enjoys the gift of working posthumously, eternally. In his power to sign decrees, even if his hand doesn’t move, maybe with his eyes closed. But also in his ritual vestments and inflections, his related figures and his clowning made divine. Detached from the sovereign’s body, auctoritas seems to have been socialized in an expropriation of his gestures, humor and other shady areas of his persona, as an outcome of his signature’s expropriation. A passel of graffiti-scrawlers, designers and tattoo artists repeating the gesture of the groupuscular surrounding the leader, copying, forging. Re-appropriating the signature, reaffirming it time and again until the forgery is cloaked in truth; doubt regarding the validity of this death-signature, smothered by the reaffirmation of the gesture of appropriating it. We could ingenuously celebrate the collectivization of authorship or authority, with a nice “We’re all Chávez,” but not everyone shares in the privileges associated with Chavism. And, if in the realm of arts and politics the word collective hearkens to horizontality and plural, shared, almost festive authorship, in the Chavist dictionary it’s synonymous with terror. To say collective in Venezuela is to speak of young men on motorcycles scattering brains with impunity. Colectivo: that’s what you call the civilian murderer who, armed by the mob and commanded by power, allows Chavism to blur the authorship of the sundry murders it orders. Otherness as legal phagocytation: expropriate the signature of the other, exert agency over the other being. Collectivization of the president’s signature thus becomes a condition of unpunished evolution in macabre plural.

What’s more, the signature of a powerful dead man, in the Afro-Caribbean milieu and in light of the popular and religious beliefs surrounding us, calls up the idea of an incantation or spell, wherever it may be reproduced: bodies, buildings, screens. But the slightest attention paid to these religions throws a special light on the functioning of the signatures we see everywhere. In Palo Mayombe, increasingly popular among Venezuelans, a signature is a set of strokes capable of calling up the power of the dead. Dimagangas, i.e., signatures: drawings with supernatural power. That’s how the pointy strokes of the omnipresent signature wish to be read. A doodle that, spread over assorted surfaces, with no distinction between human bodies and pavement, would seek to make a show of its capacity for subduing the living, of having agency over those no longer there. Signing buildings, tattooing signatures, public works, the public and mineral rights exploitation…what is taking place is an act of voodoo propaganda. A groupuscule of the privileged maintains the masquerade; the successor and some acolyte sing and dance, decreeing more holidays; the public dons masks to face the hunger bomb. A mad, carnivorous, neo-feudal carnival with ever skinnier people and ever more obese leaders, the double body of the new sovereign fashioned from the real flesh of a skeletal populace, each citizen contributing an average of eight kilos in common weight loss, as the signature would have it. After all, power is maintained as much by circuses as by states of emergency. Bolivarian normality, a state of carnivalesque emergency extended all year long. A totalitarian artwork that had to reinvent a made-to-order religious apparatus, in a neo-primitive return to lost unity. A festive, macabre return in a fusion of knowledge and flavor. Dead or alive, it seems like the author fancies haute cuisine and this is an anthropophagic banquet. You eat and, seeing the human disappear, you shut up. The force of neo-anthropophagic barbarism: in this country, it can come as no surprise that the source of power follows its own logic; the practice of cannibalism has been established here since time immemorial. The Yanomami still do it as a form of ingesting the qualities of exemplary, heroic individuals and letting the weak go in a kind of flipside to the power of death that strikes us as quite rich in humanity. But the savages that show off the power of Chavism are simple thieves, traffickers and murderers. It’s been a year since the state-of-emergency was decreed, as well as a year out from the profanation of the tomb of the first democratically elected president, Rómulo Gallegos, and to what end it goes without saying. Even more than his signature, the first democratically elected president’s skull is a first-rate source of power, like a petroleum deposit, like the ID numbers of now-deceased voters. Tomb-desecration as the order of the day, the human-bone-trafficking mafia ranging ever wider, alongside official complicity. The con-man side of santería is State religion and business. An open secret. What can be hoped for Chávez’s body after what Simón Bolívar’s exhumation kicked off?

Let’s imagine the visuals: the successor and his retinue, locking in their power-perpetuity. Is it so crazy to think that at the moment of the signature’s usurpation, they served some brew, seasoning the drink with some tiny, ground-up bone from the commandant’s body? This is no alternate reality; this is beyond habitual in Venezuela. Antigone would be wildly fortunate in comparison to any relative of the victims that were taken into Bello Monte morgue, that were buried in the cemeteries that are being emptied out all over the country. That they return your father or brother to you as a glob of pus; to have to imagine your grandfather’s bones, your son’s, the bones of those killed in the protests, dusted in chalk and splattered in wax, amid feathers, not knowing where to take the flowers, this is the Chavista promise. Let us not forget: in the Venezuelan necrocracy, a rabidly rich petro-state that doesn’t depend on taxpayers economically, power oozes right out of the ground. Its logic is that of savage extraction and unscrupulous exhumation, in an expropriation of the individual as phagocytic, demonic oblivion. So it can’t be surprising, through the lens of this singular god-state, that they’re killing citizens: the best citizen in Venezuela is a dead citizen. When you can despoil natural riches, wooing voters and collecting taxes is just a waste of time. Democratic ways, like citizens, die. Dead presidents sign off just as dead people vote, in a utilitarian harangue from beyond the grave. The federal deputy from Amazonas province, an indigenous man stripped of his office, comes from having invoked the Baniva curse on Chavism, as if he knew the game-board were increasingly controlled by those no longer here.

*

Every success in the art realm requires active participation from a model reader. It’s complicated to imagine any environment in which critics manage to escape their authorial (i.e., their authoritarian) function. Like all auctoritas, the artistic form of the State demands a proper management of the economy of recognition. Chavism was well received by its audience, but also enjoyed theoretical support, critical acclaim that persists, if only in silent tolerance.

In the Roman Empire, authors were those who certified sales and Venezuelan authoritarianism urgently seeks to recuperate that author. The ulterior end behind all the State’s banging about in recent times, seemingly on the road to consolidating dictatorship, is not so much dictatorship as it is legalizing the nation’s wholesale liquidation. To change the constitution to, legally, authorize the dumping of resources and mineral rights on the international market. And just as art critics think twice before writing against the artists with whom they have worked, especially if they’ve been on the receiving end of donated artworks, intellectuals have a hard time writing against the Venezuelan State. It would not be inconceivable, therefore, to suggest the silence we’re speaking of is rubbing up against banking secrecy. It’s not even necessary to prove Chavism’s finance-capital diversions to the intellectual classes to explain its complicit silence in purely monetary terms. For intellectuals, quite often, saying anything related to this barbarity means mass denial. This totalitarian artwork has few critics. At this point, an intellectual who questions the Chavista apparatus will necessarily question the vast majority of thought on the act, ideology regarding hunger and notions of execution, largely understood as murder. For every author, this mass denial operates both retroactively and into the future as a loss of credibility and the intellectual’s stock in trade posits credibility as a principal value: credibility, authority, authorship.

It’s worth remembering the Sophists’ money/knowledge dilemma, which emerged alongside writing on minted coins. In Greek, the word for word (sēmē) is synonymous with that for coin. Words are payment. So many authors’ support or silence, when the territory is sold off, is simply necessary to the speculative process, in both senses of the word, from theory to futures markets. Even when they stay silent on Venezuela, intellectuals are speculating. Having written on Chavism or its ideological fundaments means necessarily having participated as an investor. Shareholders in deed and thought, word and omission, complicit if not criminal silence. Acquaintance makes the heart grow fonder, even with murderers; affection is a value worth preserving. Omertà, onerous omertà. The Libertador Prize is 150 thousand dollars, the Pulitzer a mere ten. Business is business.

But the function of the author as we understand it today is born of a desire for punishment. The authorial function arises from attribution, not unlike the Holy Inquisition. Author: concrete body, subject to laceration, to whom the subversive discourse is assigned. The authorial function is a sub-product of authority; authorship a control apparatus. To understand the situation it might serve us to imagine authors reading about the death of the author with a particular fear of death. They probably smell capital punishment’s approach as they read long-gone philosophers. The specter of punishment would explain why authors remain silent before Venezuela’s authoritarian drift after almost two decades of legitimating revelry. But it’s more likely a desire for death, coessential to the authorial function, is at work there. My enemy’s enemy is my friend is what intellectuals seem to affirm when they say nothing about Venezuela, in an extension of that maxim where, by other means, philosophy is war. A diffuse war, yet predatory and inhuman. The expression socialism or barbarism thus insists on presenting itself not as a proposition of alternatives but instead as being indistinct or in coexistence, and well into the twenty-first century: both terms, socialism or barbarism, mean the same thing. Thought lays waste to cultures and natural resources, moved as always by the thanatic charge inherent to the authorial. Human, humus, inhumation, exhumation: humanism, from the petro-Venezuelan perspective, turns out to be utterly inhuman. Faced with silence from audiences, it’s hard to gauge satisfaction levels. Or if world authors’ libido spectandi, the phantasmagorical lust for death inherent in the authorial function, is being met. If there are enough red pixels on the other side of the screen. If a contemplation of the death that moves through Venezuela calms the author’s anxieties when facing his own.

*

We hope the list of authors who ought to undersign this text will not expand: Jairo Johan Ortiz Bustamante, Daniel Alejandro Queliz Araca, Miguel Ángel Colmenares, Brayan David Principal Giménez, Gruseny Antonio Calderón, Carlos José Moreno, Paola Andreina Ramírez Gómez, Niumar José San Clemente Barrios, Mervins Fernando Guitian Díaz, Ramón Ernesto Martínez Cegarra, Kevin Steveen León Garzón, Francisco Javier González Núñez, William Heriberto Marrero Rebolledo, Robert Joel Centeno Briceño, Jonathan Antonio Meneses López, Elio Manuel Pacheco Pérez, Romer Stivenson Zamora, Jairo Ramírez, Yorgeiber Rafael Barrena Bolívar, Kenyer Alexander Aranguren Pérez, Albert Alejandro Rodríguez Aponte, José Ramón Gutiérrez, Ángel Lugo Salas, Estefany Tapias, Natalie Martínez, Almelina Carrillo Virguez, Renzo Rodríguez Roda, Jesús Sulbarán, Luis Alberto Márquez, Johan Medina, Christian Humberto Ochoa Soriano, Juan Pablo Pernalete Llovera, Eyker Daniel Rojas Gil, Carlos Eduardo Aranguren Salcedo, Yonathan Quintero, Ángel Enrique Moreira González, Ana Victoria Colmenares de Hernández, Maria de los Angeles Guanipa Barrientos, Armando Cañizales Carrillo, Jesús Asdrúbal Sarmiento, Gerardo Barrera, Luis Eloy Pacheco, Daniel Gamboa, Carlos Mora, Hecder Lugo Pérez, Miguel Joseph Medina Romero, Anderson Enrique Dugarte, Miguel Fernando Castillo Bracho, Luis José Alviarez Chacón, Diego Hernández, Yeison Mora Castillo, Diego Fernando Arellano Figueredo, José Francisco Guerrero, Manuel Felipe Castellanos Molina, Paúl Moreno, Daniel Rodríguez, Jorge Escandón, Edy Alejandro Terán Aguilar, Yorman Ali Bervecia Cabeza, Jhon Alberto Quintero, Elvis Adonis Montilla Pérez, Alfredo Carrizales, Miguel Ángel Bravo Ramírez, Ynigo Jesús Leiva, Freiber Pérez Vielma, Erick Antonio Molina Contreras, Juan Antonio Sánchez Suárez, Anderson Abreu Pacheco…

Comments

There are no coments available.