18.04.2022

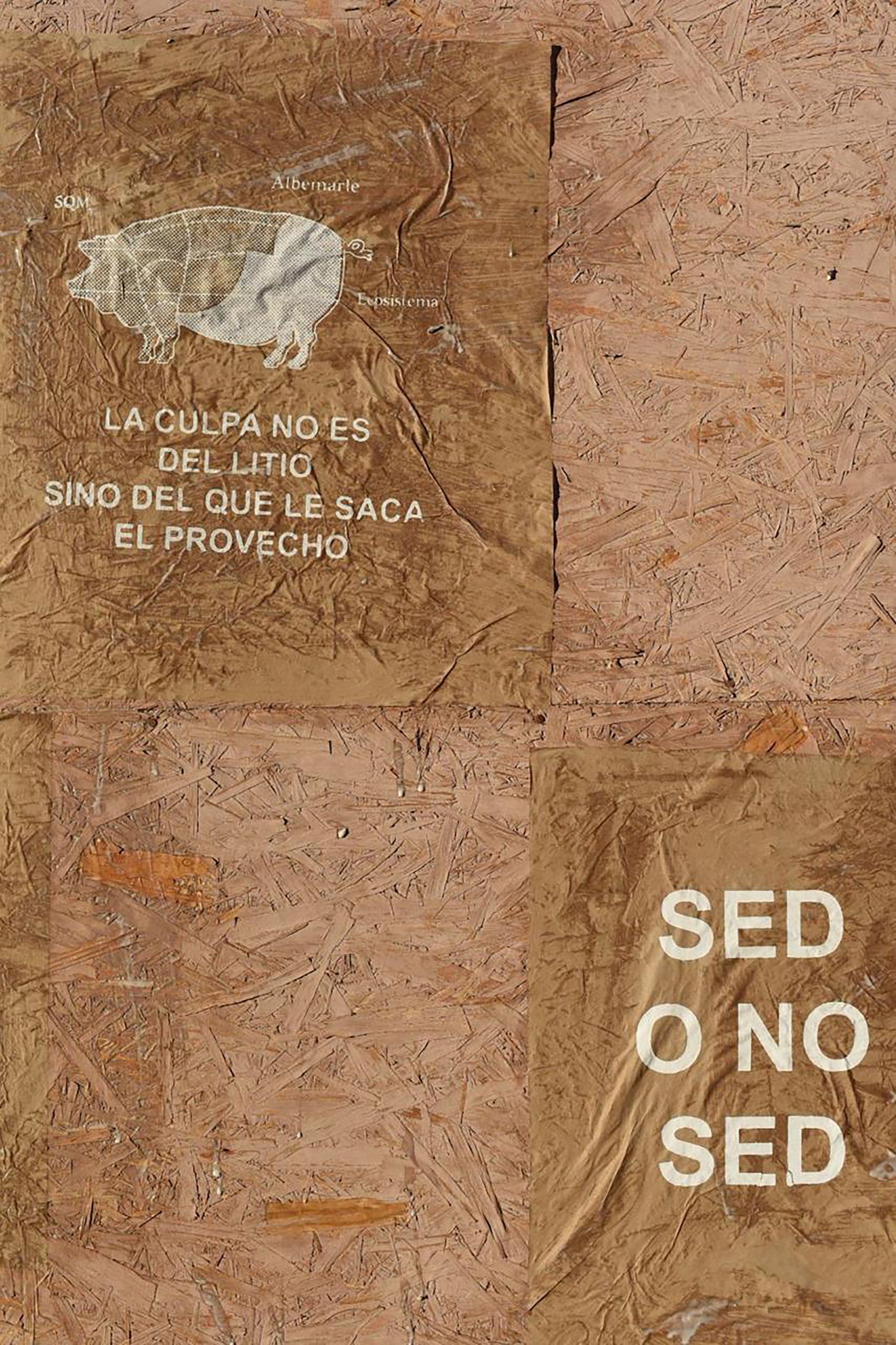

A banner with the phrase “Wounded Desert” produced under the context convened by the Laboratory of Graphic Arts of the Atacama Desert (LAGDA 2021) motivates researcher danie valencia sepúlveda to ask themself about the relationship between capital, freedom and mental health: What if life is not useful?

In his clinical texts of 1959, Frantz Fanon spoke of the pathology of freedom in reference to mental disorder. He understood mental disease as placing the patient in a world where his freedom, his will, and his desires are violated by obsessions, inhibitions, and anxieties such that the feeling of freedom could only be sustained and experienced in opposition to an oppressor, moving away from the idea that that same freedom could be built outside the parameters that the doctor himself designated. Is freedom not a specific way of producing subjectivities and undermining collectivities even in our contemporary context? Isn’t freedom one of the paradigms that convey capitalism?

There is the murmur of a message in the air; it is trying to reach us. It repeats over and over again as if it were a sigil. The impossibility of capture is in the air, and yet, in that same polluted air, poisoned, dominated, and capitalized on by white supremacy, the false idea of freedom is administered. The message that is being transmitted is that they have become exhausted with reading/listening/behaving according to the specific terms that have been positioned as key tools in the search for vitality(ies): whiteness, coloniality, epistemic extractivism, racism, colonialism, anticoloniality, REPARATION, restitution, whiteness, communality(ies), chrononorma, social justice, resistance, reappropriation, cisgenerity, transphobia, COLONODESCENDANT, wound, trauma, ANCESTRALITY, names, and surnames.

I am writing this text with two hands but with more than ten voices, which have been reverberating with the same ideas I now share here as I try to transform provocation into a channel for transmitting the infection, finding interlocution, and thus propitiating rupture.

“the-world-as-we-know-it” is configured from the experience of the total and symbolic violence that the world administers, distributes, and disseminates.

This last formulation (left vs. right) constitutes one of the most dangerous traps of Western epistemology, not only because it determines the only two fields of action, but also because of the relational codependence that it establishes in social activity. Leaving aside the fundamental role that the colonialist-capitalist framework plays in the construction of the world—even within the delirium that sustains the idea of democracy as the pinnacle of freedom—it is along this line of thought that Ailton Krenak points us in his book Life Is Not Useful:

Capitalism even wants to sell us the idea that we can reproduce life, that we can even reproduce nature. Let’s use everything up, then just make another [world], let’s use up fresh water and then make a fortune desalinating the sea and if that isn’t enough for the whole world, we will eliminate a large part of the human population, only retaining the potential consumers. A sort of Big Brother ruling the world from the desire of capitalism.[6]

The desert as a wounded body, the desert as a plundered body, the desert as a dismembered body, the desert as a ghostly body, the desert emptied and placed as an ontological principle where whiteness and colonial-capitalist coloniality build their foundations. The desert as a time bomb, the desert as a time-bomb body, and the body as an exploited, resold, exhausted, and discarded mine.

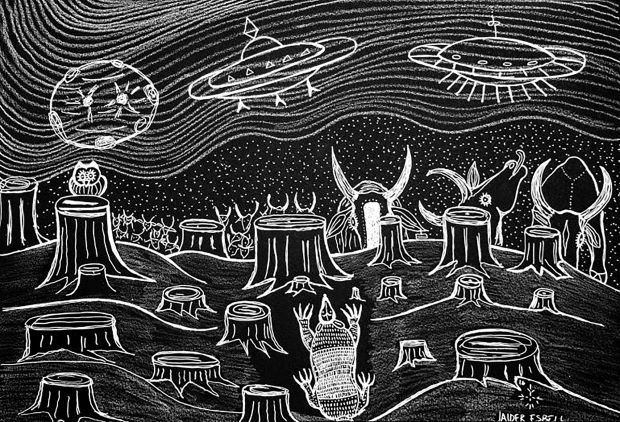

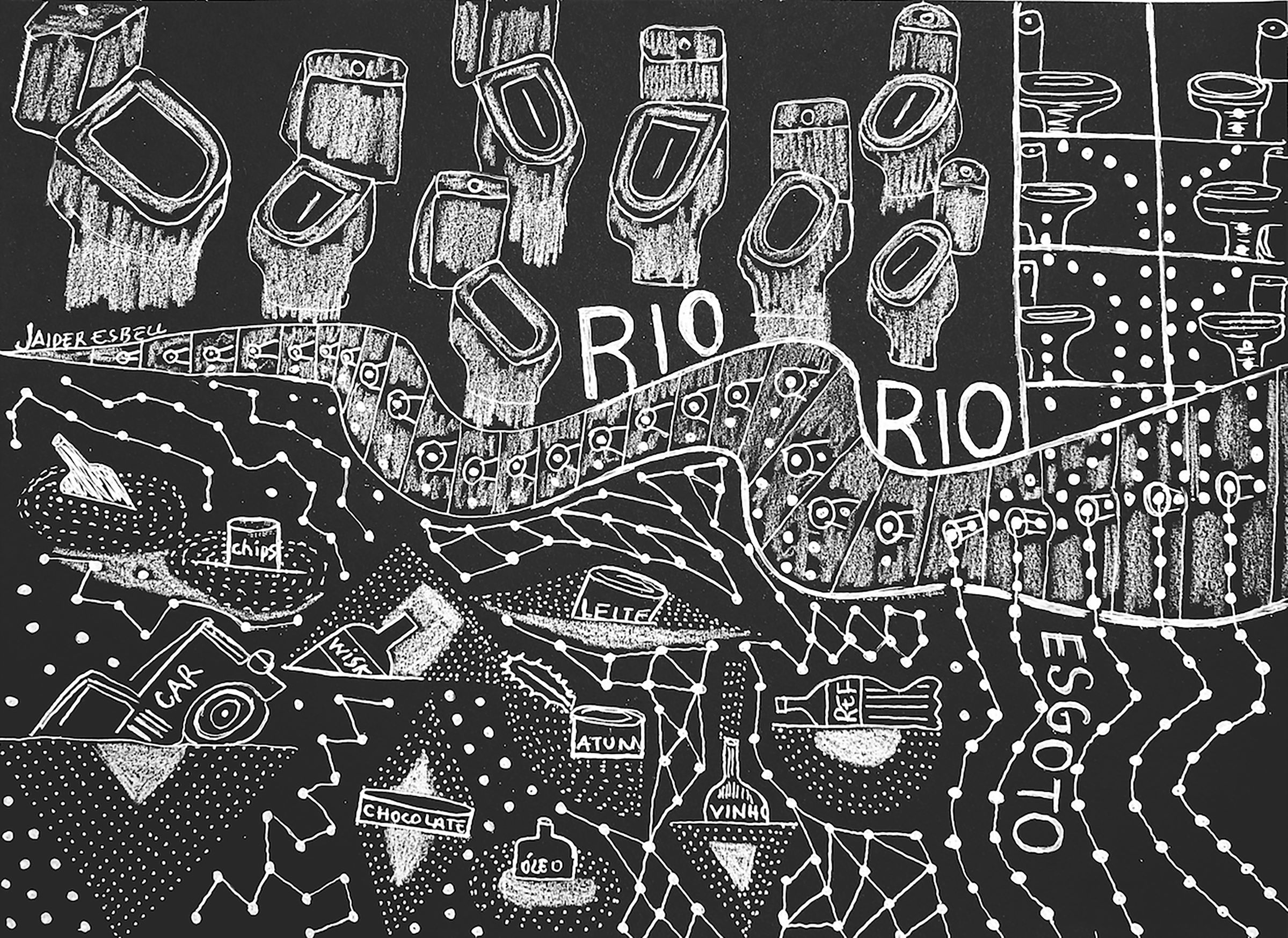

I’d like to suggest that the occupation of the landscape is a strategy for approaching indigestion, a tool for dismantling the imaginaries that sustain the credibility of the cistem, the same ones that have been attached to discourses of the nation and now continue to support the delirium of freedom and its capture. To occupy the landscape is also to dispute memory and its state guardianship, a memory that is also constructed through visuality. This is a dispute that leads us towards visual resistance; thus, it is all about approximations and processual constructions, where error and failure play the role of catalysts for holding onto the possibility of reconstructing worlds we don’t yet know. To paraphrase the Macuxi artist, curator, and writer Jaider Sbell speaking on his work: when the world ends no one will be saved, we will reconstruct the worlds that we have been denied to sustain, worlds that will have to go far beyond visuality, starting from it and allowing us to be affected by the different layers that compose it. It is a poster, a silkscreen, a collage, a video essay in viral languages. Not only that, it is also a package of elements that frames and accentuates the crisis in sustaining the world, to relocate our lives above all things, because from here we will not obtain any certainty.

the occupation of the landscape is […] a tool for dismantling the imaginaries that sustain the credibility of the cistem

I see in the proposal to take up rewriting, unlearning, and disengagement as ways that allow us to sustain the fight for vitality in its diverse forms, a possibility against the very logic in which knowledge, expertise, and their capitalizable discourses are structured. Recovering the body-territory from the provocation of repairing the total value extracted from our territories, uncaging the words that were sown to direct the monoculture of what we insist on naming the-world-as-we-know-it.

[…] there is no freedom in a world where options are only possible through coercion

Because the individual will not be cured on the couch or by subsidies from pharmaceutical companies, the cure is collective and is to be found within the structure and its possible dismantling. For, in order to end the plague, it is necessary to stop sustaining the monoculture; to recognize that individuality is just another political fiction that must be diluted; to reforest our imaginaries, allowing the invisible to lead us, not to gain freedom, but to rupture the delirium it provokes within us.

In memory of Jaider Sbell and against all forms of violence towards our bodies and experiences in this world[10]

Karkará Tunga is an indigenous artist, writer, curator, and filmmaker from Serra dos Caboclos, Pernambuco, Brazil. His text Arte-Vida, Arte-Muerte (Art-Life, Art-Death) will soon be published in Spanish, for which I thank the author for the kind and previous sharing.

As a political decision, I try not to use terms such as Latin America, a term that has historically served the expansion and triumph of coloniality in those territories.

Rizvana Bradley and Denise Ferrerira da Silva https://www.e-flux.com/journal/120/416146/four-theses-on-aesthetics/.

I am very grateful to Pésimo Servicio collective and to those involved in LAGDA for their accessibility and collaboration in the creation of this text.

Excerpt from the minutes presented at the public hearing of the knowledge commission by Laboratorio de Artes Gráficas del Desierto de Atacama (Graphic Arts Laboratory of the Atacama Desert).

Ailton Krenak, A vida nao è útil. Companhia das letras (Life Is Not Useful: Company of Letters), 2020.

I’ll run the risk of elaborating this idea according to the contributions of professor Fabian Villegas and researcher, linguist. and Ayuujk intellectual Yásnaya Elena Gil Aguilar. For Villegas, the mestizo (at least, in our lands) is and has been a metaphor for sophistication, development, and modernity that has been mobilized along with policies of whitening as a tool for constructing models of citizenship and subjectivity that ultimately translate into forms of territorial ordering, cultural policies, linguistic policies, forms of racial stratification, and even the politics of affection and regimes of desire (sic). For Gil Aguilar, who is also an activist, mestizaje is nothing more than the de-indigenization of populations for the sake of the ideological and material support of the nation state itself.

Suely Rolnik, 2015. A conversation with Suely Rolnik / Interviewed by Aurora Fernández Polanco and Antonio Pradel. Re-visiones (#5, Madrid).

Ailton Krenak, 2020.

Comments

There are no coments available.