25.03.2019

The artist Daniela Ortiz outlines a critique of the logics of colonial order that regulate the ways of collecting and exhibiting art in Europe, while seeking to unveil the games of power founded in the management of plunder that have done nothing but to historically oppress Abya Yala peoples and territories.

On July 13, 1944, the dictator Francisco Franco and his wife, Carmen Polo de Franco, opened the Museo de América [Museum of America] in Madrid. The pieces from the collection of the Real Gabinete de Historia Natural [Royal Cabinet of Natural History] were plundered from the towns and territories of Abya Yala [1] during the colonial period. This collection is still on display today. The current Spanish cultural authorities explain that several of the pieces were “offered to the Crown” by the “conquerors” themselves, through them we are reminded of some pillars of colonial order: the plundering of cultural representations of the people of Abya Yala, the abduction by European and/or eurocentric institutions, and the interpretation and use of the pieces for political gain in order to sustain certain historical narratives and discourses imposed by the colonizer. In this way, an imaginary is implanted in the artistic manifestations of the oppressed people. The colonial order creates a binary logic of indigenous people as sacred and connected with a higher spiritual world, which is counteracted by the imaginary threat of violent Indians who put at risk the welfare and impunity of the white population.

This cultural imaginary reproduces the logic of racism through paternalism and criminalization. Terms such as old civilizations, ruins, pre-Columbian, pre-Hispanic, have for over 526 years conditioned the visual, poetic, and cultural narratives surrounding the peoples of Abya Yala. European power, through its museum machinery, creates its own narratives about the colonized communities. It works to sustain the policies of violence and dispossession that allow for the accumulation of capital in Europe. This machinery does not use silence or deny the existence of non-European peoples, but rather formulates interpretations and truths about them.

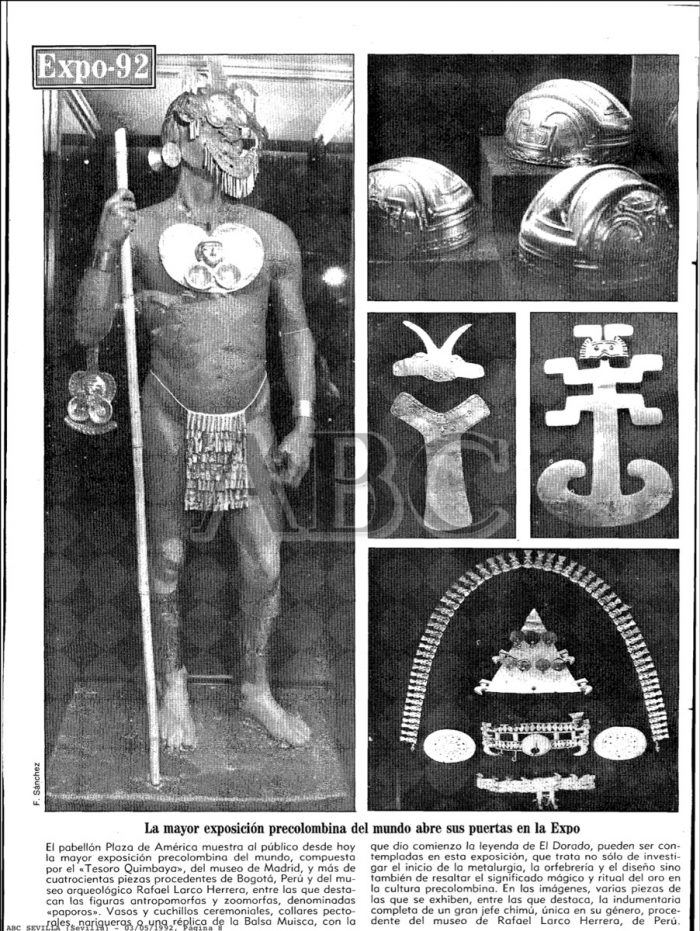

A news report in 1944 by the dictatorial regime of Franco narrates the opening of the Museo de América. One of the highlights of museum according to the report is the so-called Tesoro de los Quimbayas [Treasure of the Quimbayas], a series of gold pieces of human figures taken at the end of the nineteenth century in Colombian territory. The plundered pieces were initially sent to Spain in 1892 on a steamboat named “Mexico” operated by the Compañía Trasatlántica de Barcelona and owned by the colonial businessman Antonio Lopez i Lopez. This shipment arrived in the context of the Colombian Republic’s participation at the Conmemoración del IV Centenario del Descubrimiento de América [400th Centennial Anniversary of the Discovery of America], one of the many celebrations of colonialism.

The participation in this event by the republics of Peru, Bolivia, Colombia, and Ecuador is symptomatic of the continuation of the colonial order, hardly seven decades after their declarations of independence. The creole declarations of independence were the beginning of a new formula for continuing the colonial order through the creation of nation-states. Through eurocentric political, social, and economic organization they maintained a racialized social structure imposed on the people of Abya Yala and prolonged the functioning of racial capitalism.

The exhibition of the pieces made by the Quimbaya community is a cultural device for the celebration of colonialism. The pieces were donated to Queen María Cristina by the Creole white president of the Republic of Colombia, Carlos Holguin, in an act of gratitude for the intervention of the Spanish crown in a border conflict between Venezuela and Colombia. In this conflict, both nation-states legitimized the Spanish monarch to determine the frontier between the two countries. The imposition, and recognition of geographical borders reinforced both the internal colonial system, as well as appealing to the colonial power to once again, impose its position on the territory of Abya Yala.

It is confronted in a categorical way, from the symbolic, to the image, to the imaginaries, and the action in front of a system of death and dispossession imposed by a colonial order.

Native gifts as a colonial offering were first presented in 1892 Another large number of plundered objects that originated in the oppressed towns of Abya Yala were offered to the different leaders of the Creole republics. Later, in the 1940s, the “treasure” became part of the collection of the Museo de América. The museum also exhibited a collection of objects expressly sent to the Spanish regime by the white-Creole elites who controlled the governments of the American republics. These elites assumed the role of the colonizer and, in agreement with the power of the metropolis, developed new institutional, legal, discursive, and structural formulas to maintain colonial order. These colonial alliances and cultural policies are constantly reproduced in the history of so-called Hispano-América.

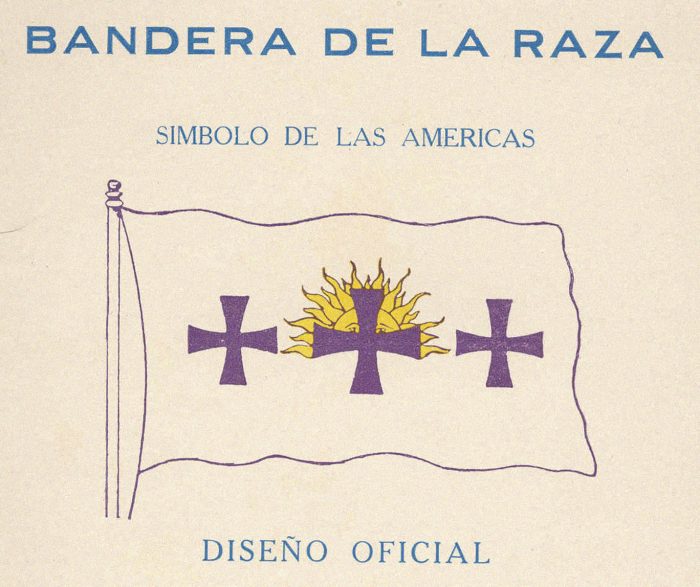

During the celebrations of October 12th, in the year 1932, in the Plaza Independencia of Montevideo, the Bandera de la Raza was raised for the first time. The flag was also called Bandera de la Hispanidad [Hispanic Flag or Flag of the Hispanicity] and was officially adopted in 1933 by all the nation-states imposed on Abya Yala within the framework of the Séptima Conferencia Panamericana [7th Pan-American Conference]. In fact, the flag is white to represent peace as well as to remember the white of the flags of the Spanish empire; the three crosses are described as Mexican or Mayan, but also allude to the candles of the three caravels [sailing ships] that “discovered” America—the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María; and finally the Inca sun (as claimed by the creators of the flag) as a symbol that represents el despertar del continente americano [the American awakening]. If no contradiction arose with the fact that a republican government celebrated the flag of “race” or “Hispanicness” in commemoration of the beginning of colonialism on the continent, in a place called Plaza de la Independencia [Independence Plaza], it is because, as Houria Bouteldja explains, “these independences did not mean the end of colonialism. [2]” In fact, in the design of the flag, the logic of co-opting the symbols of oppressed people are repeated, to resignify its interpretation with the discourse of mestizaje. In doing so, this conceals the imposition of whiteness as a racial policy and makes the Indian, Afro, and indigenous resistances invisible against these policies. It normalizes the violence of a struc- turally racist institutional order that exploits and exterminates native communities.

In the same historical timeline, we can locate the participation of the mayors of the capitals of the creole nation-states—as well as the ambassadors of those countries—in the inauguration of the Plaza de Colón in Madrid in 1977. This time with a “democratic” government of the white left, the Spanish authorities used the public space and the location of the Jardines del Descubrimiento [Gardens of Discovery] to express their will to sustain themselves as oppressors within the colonial system, and their need to maintain control of the territories, people, and resources of Abya Yala. To this effect, in the ceremony it was not only necessary to have king Juan Carlos de Borbón and queen Sofia of Greece, but also the presence of the Latin American Creole authorities. In the ABC newspaper, it was noted that the Latin American Authorities “deposited land of their respective countries in homage to the feat of discovery.” Two decades later, the Creole authorities returned to be part of major events organized by the Spanish government for the celebration of five centuries of the colonial rule. In this context and 100 years after its first exhibition, the stolen art of the Quimbaya was once again shown in the Exposición Universal de Sevilla 1992. The narrative imposition of artistic expressions was once again produced from the persecuted people of Abya Yala. At the same time, on October 12 in Chiapas, Mexico these same people—not in ruins, but alive and in resistance—knocked down the monument of the colonial settler Diego de Mazaraniego and subjected him to a ritual of anticolonial reparation. This action was followed by the demolition of the monument to Christopher Columbus in the city of Caracas in 2004. These along with many other cultural manifestations, were in opposition to the Creole ritual of offering the land appropriated from the territory of Abya Yala. In the so-called Jardines del descubrimiento and at the foot of the monument to Christopher Columbus, it is confronted in a categorical way, from the symbolic, to the image, to the imaginaries, and the action in front of a system of death and dispossession imposed by a colonial order.

Within the same protocol of cultural events organized to reinforce the colonial order, in 2018 the presentation of the International Contemporary Art Fair ARCOmadrid 2019 was held at the Centro Cultural de España in Lima during the visit of the Spanish monarchy to Peru. During this visit, not only all the authorities of the “independent” colonial nation-state opened their doors and bowed before the contemporary representatives of the Bourbon dynasty, who in 1781 assassinated the revolutionary anti-colonial Indian leader Tupac Amaru II, but the Spanish monarchy legitimized the republic of Peru as a country invited to the fair. This invitation seeks to position the country as a capitalist state in the process of succeeding within the neoliberal order and economy and ignores the colonial-style offensive led by Spain and the United States that affects the people and territory of Venezuela. Moreover, the participation and recognition of Peru by the kings in an international trade fair for commercial art such as the ARCOmadrid coincides with a time when the so-called Grupo de Lima [3], together with the Colombian government, was leading the political aggression that seemed to open the way to a military invasion that does little to respond to the needs of the Venezuelan people and that justifies the consistent strategy by the US the government (in alliance with European governments) for imperial control. In addition to exercising imperial violence on the territories of the Global South, these governments have been reproducing the colonial order inside the European territory through a system of migratory control that persecutes, detains, deports, and assassinates migrants from the former colonies. In this sense, they have managed to normalize the figure of more than seventy thousand dead and disappeared on the European borders since the nineties, and hundreds of thousands of forced deportations. Meanwhile, the authorities and embassies of countries such as Peru or Colombia operate as accomplices through their collaboration in forced deportation proceedings of their own citizens.

With the participation of Peru as the guest country of ARCOmadrid 2019, many of the Creole authorities will be offering the Bourbon monarchy its best treasures, consolidating their colonial pact and seal—with a toast in cultural events—and an agreement to defend the power of the white supremacy. Let’s hope that when the glasses are empty and there is no liquid to extinguish the flames, they reproduce not only the images of the colonial power and its aberrant use of the artistic manifestations plundered and exploited in the aforementioned cultural events, but also the image of the Pabellón de los Descubrimientos in the Exposición Universal de Sevilla during the celebrations of the V Centenario [500th anniversary of American colonialism] being consumed by a fortuitous anticolonial justice.

Abya Yala is the name given to the territory of Guna people that is now claimed by Panama and Colombia, it is also a term given to the territory of Latin America.

Saïd Mekki, “La Lucha Descolonizadora en Francia: Entrevista con Houria Bouteldja”, Grupo decolonial de traducción. <http://decolonialtranslation.com/espanol/itwhouriaEsp.html>. [Accesed February 9, 2019].

The Grupo de Lima (sometimes abbreviated as GL) is a multilateral body that was established after the so-called Declaration of Lima, on August 8, 2017, in the capital of the same name, where representatives of fourteen countries met in order to give follow-up and seek a peaceful solution to the crisis in Venezuela.

Comments

There are no coments available.